Kali Meets the Twitterati: On Mithu Sanyal’s “Identitti”

Susan Bernofsky reviews Alta L. Price’s new translation of Mithu Sanyal’s novel “Identitti.”

By Susan BernofskyOctober 24, 2022

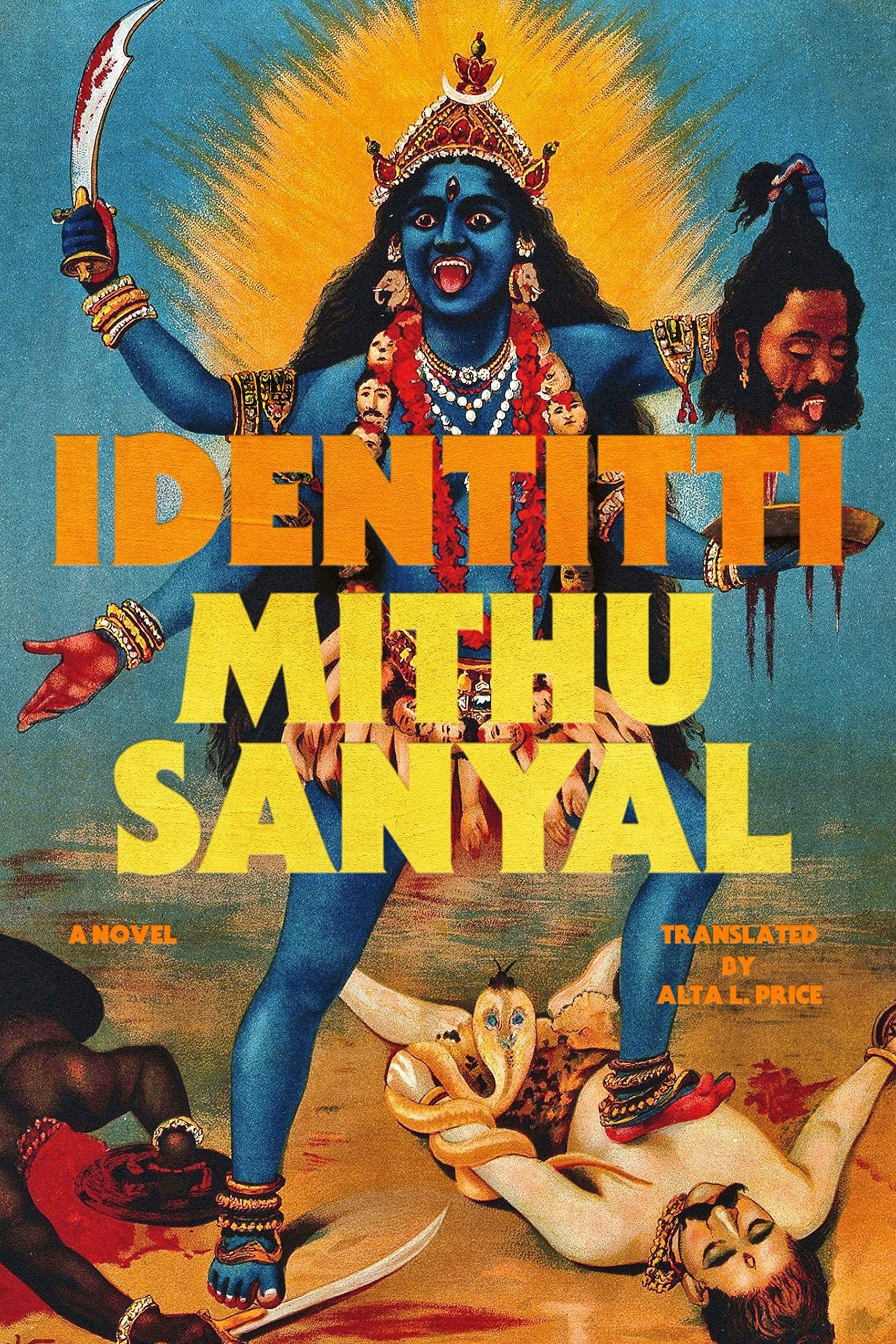

Identitti by Mithu Sanyal. Astra House. 384 pages.

IMAGINE YOU’RE a young person born and raised in Germany who’s grown up being constantly asked about your identity because you were born into a culturally mixed household and, like one of your parents, you have enough melanin in your skin to stand out. Imagine that the experience of being racialized and othered in your own country throughout your childhood and youth has inspired you to enroll in the Cultural Studies Program at the University of Dusseldorf, and imagine having a completely transformative experience there thanks to one particular professor — brilliant, inspiring, charismatic — who happens also to be a person of color, making her the role model of your dreams. Imagine this professor opens your eyes to a world of history and philosophy and postcolonial studies — ideas that she debates with her students in long, exhilarating seminar sessions that leave you thrilled and exhausted. Her reading lists are spectacular. She even takes you under her wing personally, simultaneously nurturing and challenging you, as she does with a number of her students — above all, students of color. You’re part of an intellectual community now, experiencing a sense of belonging, of being seen, of meaning and context. Your teacher — who, like the rock star she is, goes by only a single name, Saraswati — has changed your life. And then one day you check your Twitter feed and find out that she’s been outed as a white woman who’s been artificially darkening her skin and deceptively performing the identity you found so inspiring. It’s shitstorm time.

Thus begins Mithu Sanyal’s brilliant debut novel, whose main character, Nivedita Anand, is a student and blogger who introduces herself on her blog Identitti as “Mixed-Race Wonder Woman.” She writes about ideas and sex — yes, her Twitter handle puns on “titty” — and tends to have a lot on her mind and her plate. She’s involved in an interminably on-again/off-again relationship with a possibly narcissistic white dude named Simon, who seems not to appreciate the attention she’s recently been receiving as a budding public intellectual. Her female friendships are more consequential: the women she lives and studies with are crucial allies in her project of deciding and discovering who she is and what she wants to be in the world. Her other main interlocutor is Kali, the fierce man-eating, sex-positive Hindu goddess of destruction (and creation), who’s constantly chiming in with commentary on whatever Nivedita is currently thinking or doing.

When the illustrious Professor Saraswati, author of the paradigm-shifting Decolonize Your Soul, is outed as a “race fake,” the revelation provokes a wide range of responses among her students. Most in Nivedita’s circle immediately translate their sense of personal betrayal into public condemnation of their former mentor. But not Nivedita, who finds herself in a particularly awkward position: in a radio interview recorded just before Saraswati’s outing, Nivedita praises her, saying, “The people who accuse Saraswati of being racist […] don’t get what being white means to her.” Soon that sound bite is everywhere, making Nivedita officially the first (and for a long time the only) person to defend the disgraced academic. In her confusion, she turns to the individual who’s always been the most help to her in making sense of complex states of affairs: Saraswati herself. Finding Nivedita on her doorstep, the professor promptly incorporates the disoriented student into her household.

Most of the novel’s action takes place inside this apartment, where — as in a Marx Brothers film — more and more people soon congregate, each introducing an added layer of complexity. There’s Priti, Nivedita’s cousin from Birmingham (UK), whom Nivedita perceives as sharper and more self-assured than she is, and above all more Indian. Saraswati’s brother shows up, too, his story comprising its own complex plot twist. Other students arrive, other lovers. Saraswati’s home is a fancy penthouse — sunlight, balconies, Scandinavian furniture — overlooking a low-income neighborhood with a large immigrant population. In the privacy of these lodgings, the various convolutions and flip sides of Saraswati’s decision to proclaim herself “transracial” are weighed and discussed in long conversations — including lots of input from the outside world via the Twittersphere — that become the equivalent of one of Saraswati’s seminar sessions: complicated, confusing, enlightening, exhausting.

And entertaining, too. As Nivedita remarks of Saraswati at one point, “[S]he makes it easy to laugh at racism.” The same is true of Sanyal, who has an uncanny knack for turning dead-serious subject matter into a source of humor. The book is truly funny, often even cringe-funny. Possibly even Paul Beatty–level cringe-funny. Take, for example, a scene in which Nivedita’s favorite roommate, Barbara, a white girl and ally, brings home a one-night stand to whom she introduces Nivedita as “our Asian cleaning lady” who “doesn’t speak much German” — filling both women with hilarity as the guy squirms.

Sanyal’s characters spend many pages debating the theory, history, and philosophy of race and racism. Sanyal is the author of two previous nonfiction books entitled Vulva (2009) and Rape: From Lucretia to #MeToo (2016), and she certainly could have written a nonfiction book on the history of whiteness and racism instead of this novel — obviously a great deal of research went into it. But the book doesn’t at all feel like a lecture course crammed into fiction; it feels like a novel. A novel of ideas, admittedly, but also a comedy, and a novel of friendship. Dare I even say a Bildungsroman? By confronting her own fury and dismay at Saraswati’s deception — and coming to understand how exactly Saraswati’s history relates to her own — Nivedita grows up.

Not without experiencing a great deal of racism herself, however. As the German-born child of an Indian father, she goes from being called a “coconut” by her cousin’s Indian British playmates in Birmingham to seeing what it feels like to wear the sari her aunt has gifted her on the street in Dusseldorf (she’s promptly attacked by a stranger). She gets asked where she’s from so often that she starts translating the question as “[W]hy are you brown?” When she complains to her father, though, he derides her softness. Her Polish German mother, too, has childhood stories of racism aplenty to share, and it’s Nivedita’s inner interlocutor Kali who finally calls Nivedita to account for being so obsessed with the Indian side of her heritage and Indian gods, while showing no interest at all in her Polish side and the long-forgotten Slavic gods whose statues were destroyed all across Poland by Catholic missionaries in the year 966. (Nivedita shares this mixed Polish Indian heritage with Sanyal, though they’re of quite different generations; indeed, Nivedita is young enough that the name “Barack Obama” doesn’t immediately ring a bell.)

The novel’s long middle section set in Saraswati’s apartment is not without its longueurs. It’s kind of like watching some nouvelle vague movie with characters endlessly talking politics and philosophy in the kitchen over coffee and far too many cigarettes. But the time and space the book reserves for these conversations strikes this reader as a crucial part of its strategy — giving time and care for thoughts and relationships to develop and unfold. What’s at stake here isn’t simply, or even primarily, the often conflicting ideas and points of view, but rather the feelings and community that create their context. Sanyal carefully avoids passing judgment on Saraswati, instead focusing on the effects of her deception. The book eventually comes down hard on the side of “Truth and Reconciliation” — emphasis on the “and.” There can be, Nivedita decides, no forgiveness without confrontation, conversation, and a heartfelt attempt at mutual understanding.

In keeping with this sense of real-world stakes and communal striving, Sanyal — in a truly impressive literary feat — brings the real world into her book quite literally. The young people she’s writing about are bloggers, accustomed to using virtual conversations not just to stake out their positions but to arrive at them. Thinking in this book is done communally. (This reminds me of Kate Zambreno, who likes to incorporate conversations with fellow writers into her work, and Sawako Nakayasu, whose books weave in poems and lines by other hands.) Sanyal makes the blogosphere/Twittersphere of the novel overlap with the external world by quoting from actual intellectuals and bloggers; in some cases, she borrows lines from their published works, presenting these excerpts as tweeted responses to #Saraswatigate. Other lines are lifted from responses to the Rachel Dolezal scandal in the United States.

Moreover, Sanyal was able to convince a good dozen members of the Twitterati to compose tweets specifically for her novel, in response to a hypothetical situation she described to them. And so, tweets by the fictional Oluchi (a.k.a. @OutsideSisters) appear alongside tweets that real-life novelist Fatma Aydemir (@fatma_morgana, 22.6K followers) contributed to Sanyal’s book. Identitti is the rare novel that actually embodies communality. Other scenes depict Saraswati in conversation with both Kwame Anthony Appiah and the odious Jordan Peterson (in each case represented by words they spoke and wrote in other contexts). In “Afterword: Real and Imagined Voices,” Sanyal documents all of her quotations and provides a rich reading list for those interested in following up on the themes and topics the book explores. The English-language edition cites three cases of academic racial passing that have surfaced in the United States since the Dolezal affair.

The novel’s significant multilingualism poses particular challenges for English translation — which the book’s translator, Alta L. Price, has met with aplomb. In accordance with Identitti’s playfully punning spirit, she often punches up the language: Nivedita, blogging, invites Venus to “[s]cooch [her] cooch over” to make room for Kali; Saraswati’s brother is described as “über-controversial” (not how Germans use “über,” by the way — the German here was the equally funny “kontroversplusplus”); and we’re told that as long as Priti “sprinkles” Nivedita “with the stardust of her approval, Niv felt capital-N Noteworthy rather than Not Worthy.” The translation beautifully rises to the occasion of Sanyal’s lively, allusion-packed prose, nimbly adjusting the quoted matter to work in an English-language context; and Price’s postscript is a meaty, informative addition to the book’s back matter.

Identitti is a sweet and hopeful yet critical book that lovingly pays tribute to the thought leaders who inspired not just Saraswati but also Sanyal (at the top of the list are Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Audre Lorde, and Priyamvada Gopal). If only we spoke to each other more — more honestly and with more historical knowledge — about difficult topics like racism, the book suggests, we might find a way to get along. Read against the newspaper, of course, it’s clear we still have a long way to go, and the novel certainly acknowledges this reality. Oluchi and Nivedita are outraged when, in the aftermath of a particularly brutal racist massacre, political protests are temporarily prohibited. Sanyal writes in her afterword that she decided to use this attack in her novel — a white supremacist killed 11 people and wounded another five in Hanau, Germany, on February 19, 2020, while she was in the middle of writing the book — because “attacks like the one in Hanau have occurred, and continue to occur, all over the world,” and because she considers “German literature’s overwhelming silence on this topic an unacceptable omission.” Her novel goes a long way toward filling this gap.

¤

LARB Contributor

Susan Bernofsky is a writer and the prize-winning translator of seven works of fiction by the great Swiss German modernist author Robert Walser, as well as novels and poetry by Yoko Tawada, Jenny Erpenbeck, Uljana Wolf, Franz Kafka, Hermann Hesse, and others. Her most recent book, Clairvoyant of the Small: The Life of Robert Walser, was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for Biography. For her translations, she has received the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize, the Schlegel-Tieck Translation Prize, the Ungar Award for Literary Translation, the Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize, the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation, and others. A Guggenheim, Cullman, and Berlin Prize fellow, she teaches literary translation at the Columbia University School of the Arts and is currently working on a new translation of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain for W. W. Norton. Her translation of Yoko Tawada’s novel Paul Celan and the Transtibetan Angel is forthcoming in 2023 from New Directions.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Knotty Problem of Race in Three New German Novels

Debut novels by Sharon Dodua Otoo, Mithu Sanyal, and Hengameh Yaghoobifarah explore the problematic terrain of race in German literary culture.

Black Germans and the Politics of Diaspora: On Tiffany Florvil’s “Mobilizing Black Germany”

Samuel Clowes Huneke reviews Tiffany Florvil’s “Mobilizing Black Germany: Afro-German Women and the Making of a Transnational Movement.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!