Inside Out: Moments of Affinity in Xue Yiwei’s “Celia, Misoka, I”

Megan Walsh reviews “Celia, Misoka, I” by Xue Yiwei.

By Megan WalshMarch 4, 2022

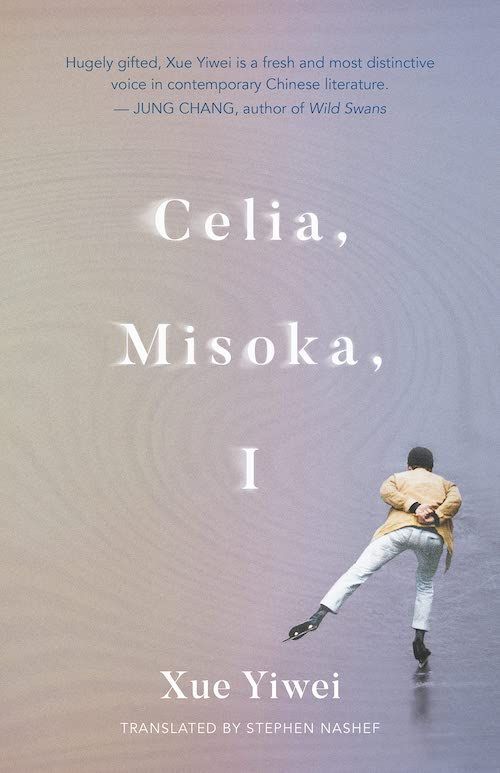

Celia, Misoka, I by Xue Yiwei. Rare Machines. 280 pages.

THE CHINESE-BORN NARRATOR in Xue Yiwei’s latest novel, Celia, Misoka, I, has been living in Montreal for 15 years. Out of the blue, an old classmate in China begs him to convince his hesitant wife that they too should emigrate to Canada. Over a long-distance phone call, the narrator dutifully encourages her to move. What he chooses not to say, however, is his belief that immigrants, even if they have money, face unavoidable difficulties “like solitude, humiliation, and monotony, like repetitiveness, directionlessness, and helplessness.” His hidden feelings reveal the often private anguish of leaving one’s native home, culture, and language, and specifically, how it is hard to truly know if leaving was the right decision. Much of Xue Yiwei’s prolific output as a novelist has dealt with individuals looking for signs or coincidences to make sense of their internalized feelings of doubt and alienation.

Born in 1964 in Changsha, Hunan province, Xue studied and worked in Beijing, Shenzhen, and Guangzhou before moving to Montreal in 2002. From here he writes “outside the system,” so to speak. His style reflects a fusion of influences, but most notably the French existentialists he devoured as a young man, and he frequently writes in modes of radical subjectivity. A couple of his stories have been banned or rejected in mainland China, but Xue is considered neither a political rebel nor a collaborator. Unlike combative, dissident writers such as Ma Jian or those such as Yiyun Li and Ha Jin who have chosen to write only in English since they left, Xue flips between both languages and continues to publish most of his work in China, often to great acclaim. Of his 16 books, only three have so far appeared in English. The first of those was Shenzheners, inspired by James Joyce’s Dubliners, which is a collection of stories about people living in China’s own city of migrants, where almost everyone can simultaneously fit in and feel out of place. The second, Dr. Bethune’s Children, explored a manic, imaginary relationship between a Chinese immigrant living in Montreal and the long since dead Dr. Norman Bethune, a Canadian physician who died serving the Chinese Communist Party in 1939. The sketchy but all-consuming connection between the narrator and this unlikely Canadian communist hero was that they both left each other’s country in search of something they could not find at home.

In Celia, Misoka, I, thoughtfully translated from Chinese by Stephen Nashef, Xue Yiwei once again builds tenuous connections between outsiders. A Chinese-born immigrant recalls the time he suffered a desperate identity crisis. His wife, with whom he shared a loveless marriage, had just died from cancer, and he had sold the convenience store they ran together. His daughter, for whom they sacrificed impressive careers in China to move to Canada, had stopped speaking to him. Alone in his adopted city of Montreal, the unnamed narrator was utterly lost to himself. “I was no longer a husband, no longer a father, no longer the owner of a business,” he recalled. “Maybe no longer even really a man.” In search of a mooring, he took refuge in the past, returning daily to the ice rink at the top of Mount Royal, the rocky outcrop at the heart of the city, that he used to visit with this daughter. It is here, in this frigid landscape, that he became fixated with the two women of the title — the young wheelchair-bound Misoka who sits in the freezing cold overlooking Beaver Lake writing a novel, and the middle-aged Celia, an avid skater and Shakespeare scholar he dubs the “healthy sufferer.”

Much like Robert Frost’s poem “Design” evokes the uncanny combination of a white spider, holding a white moth, on a white flower, the unnamed narrator dares to imagine that some strange fate has brought the three of them together. He sees himself as mysteriously and poetically linked to both women — one of Chinese and Japanese heritage born and raised in French-speaking Quebec and the other a middle-aged divorcee from Montreal. Their daily presence at the rink gives him something to live for and obsess over, splicing his own fantasies about who they are, what they mean to him — and what he means to them — with only snatches of real-life conversations to fuel his “unruly imagination.” Crucially, one of the most intriguing things about Misoka and Celia, for the narrator at least, is that both women hint at strong, if unforthcoming, views about China itself. Xue expertly skewers the protectiveness the narrator feels about the country that he has left — and arguably no longer knows very well — as he shuffles memories of his bookish youth and early romances in China in with his pragmatic move to Montreal and the intrigue of his unfolding relationship with both women.

It is, at times, hard to feel the same wonder about this possible love triangle as the narrator does himself. This could be down to the author’s tendency to overexplain or marvel a little too much at his narrator’s flights of fancy. And there is a niggling sense of unease about a man, caught up in his loneliness, seeing in women a subtext, or story, where there may not be one. But this obsessive mindset might also be an intentional ruse on the part of the author, who knowingly blurs the line between fantasy and reality. Just as the narrator mirrors some of the author’s own biographical details, his three main characters all use writing — and reading — as a private act of emigration in itself, a way to cope with the persistent reality of their sadness and loneliness. And this dream-like mode of being does bring them together, if only briefly.

He describes the three of them as “grains of sand,” randomly tossed together and blown apart by the “winds of globalization.” And the novel is in fact less a tribute to the immigrant experience than it is to the generalized disconnection of the globalized age, elevated by moments of unexpected affinity. The most delightful parts of the novel are recollections of people: the local outliers and eccentrics of the narrator’s childhood or the customers at the convenience store — a university lecturer from Saint Lucia, the mobile phone addict who despises the information era — who appear briefly in person, but irrevocably change his worldview. Ultimately, Celia, Misoka, I is about the importance of storytelling in this “age of chaos, marked by the collapse of authority, the destruction of the individual, and the disappearance of meaningful relationships.” The narrative, no matter how fanciful or flighty, captures the possibility and promise of meaningful connection.

As an examination of what can be lost — and found — in the process of uprooting oneself, geographically and psychologically, Xue’s writing offers consolation for the challenges of estrangement and longing. And, unlike his fictional counterpart, he continues to live and work in Montreal, exploring what his narrator sees as the “huge gulf […] between what [he] experienced and how [he] wrote about it.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Megan Walsh is a journalist and critic currently based in London. Her book The Subplot: What China Is Reading And Why It Matters is published by Columbia Global Reports on February 8, 2022.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Dreaming Freely: On the Ecstatic Fictions of Can Xue

Bailey Trela considers “I Live in the Slums,” the recently translated short story collection by Can Xue.

Communing with the Dead: On Yiyun Li’s “Where Reasons End”

Ultimately, "Where Reasons End" is a tremendous act of empathy.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!