Dreaming Freely: On the Ecstatic Fictions of Can Xue

Bailey Trela considers “I Live in the Slums,” the recently translated short story collection by Can Xue.

By Bailey TrelaJune 17, 2020

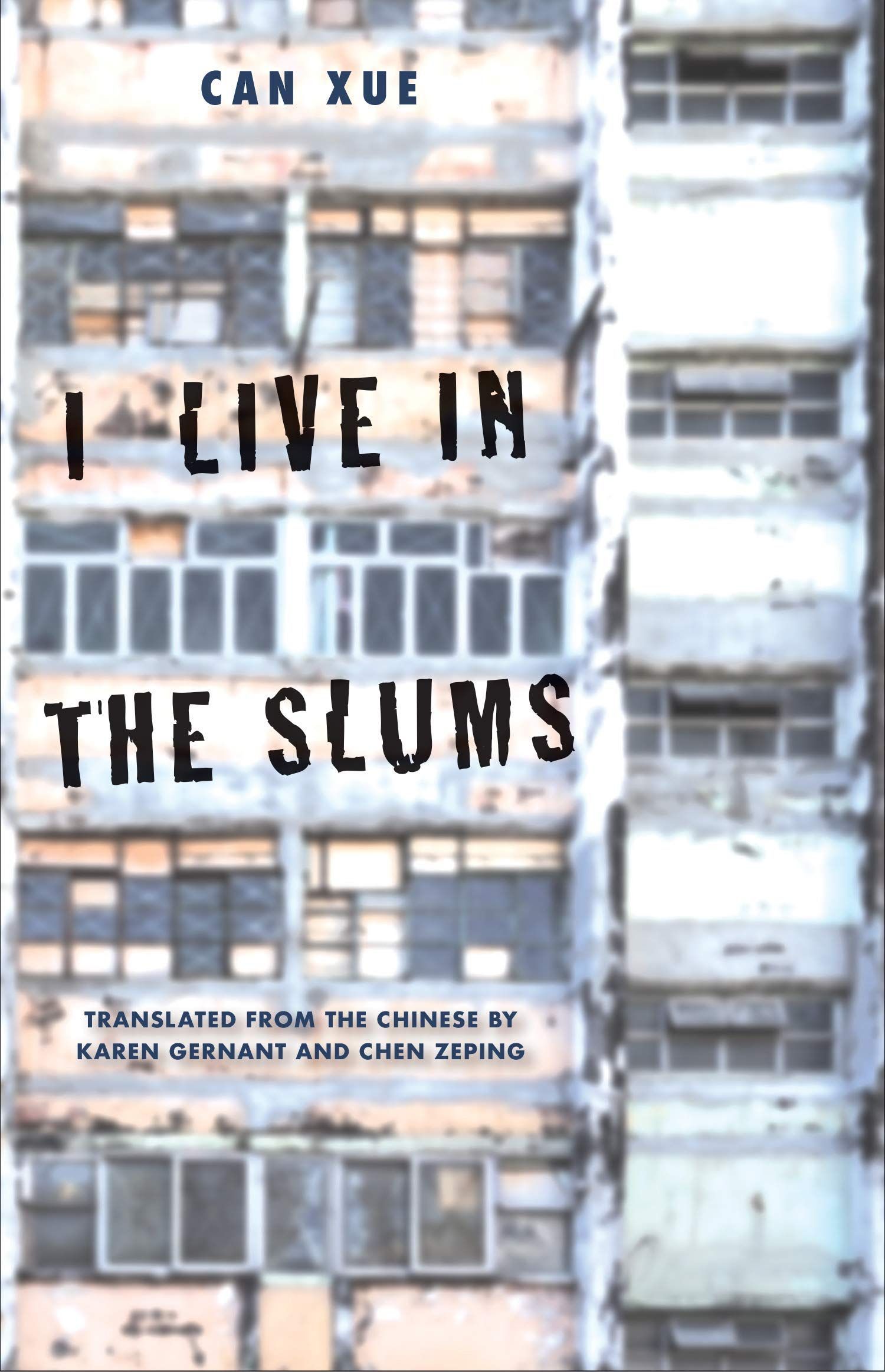

I Live in the Slums by Can Xue. Yale University Press. 344 pages.

ONE THING YOU’RE BOUND to pick up on after reading Can Xue for a while is the exuberant presence of flora and fauna in her work. Whole fields of luminous flowers grow to full bloom overnight; poisonous butterflies drift over a garden, airily sidestepping its tended boundaries; snow leopards wander down from their mountain homes to step casually through empty city streets. To read Can Xue, more often than not, is to find yourself lost in a flurry of viral growth, subservient to the whims of a radical accelerationism.

Though that’s not the half of it, as far as strangeness is concerned. Can Xue’s stories — 16 of which appear in her latest collection to arrive in English courtesy of Karen Gernant and Chen Zeping, titled I Live in the Slums — are filled with absurdly tall structures, head wounds that never heal, grotesque creatures that seem like demented refractions of commonplace pests and floating gardens, with spiritually inclined cicadas and willow trees that quietly mourn their fates. Her plots play out in cities besieged by floods, sandstorms, and perpetual fogs; where factory smoke never fades and a profound muddleheadedness afflicts the populace; where the blazing sun falls like a hammer on the helpless inhabitants, withering them into shadows.

Can Xue has written numerous novels and story collections since her career began in the mid-1980s. Your typical Can Xue outing is a silvery, mercurial concoction distilled from the bones of Kafka, Dante, and Beckett, an unstable brew that feels like it’s always on the verge of exploding into the too wildly uncanny. The world her stories take place in is at once stripped bare of details and abuzz with frantic human activity; even though a fog of amnesia creeps through her pages, it never really feels insidious. It’s better, probably, to describe it as a certain impermanence of mood, of emotion, of memory. It’s as though her characters, in search of rebirth, were nevertheless constantly being confronted with the oblivion that precedes it.

With its latent suggestion of social realism, the title “I Live in the Slums” feels like a bit of a joke. The book’s leading novella, “Story of the Slums,” isn’t so much a morally engaged statement of the facts, after all, as it is a Dantesque devolution of the self, one that follows a hazily defined narrator through a hellishly torqued, Boschian vision of slum life. There is, undeniably, a sense of hardship present in the story (“It was torture for people to live here,” Can Xue writes), but her penchant for vague, metaphysical geographies trumps the strict limning of real-world miseries. The slums, we learn, are located in a “low-lying land,” a “confusing place” that the narrator tries to leave by climbing a set of steps. The story’s verticality — the way it rises one moment to the city above and plummets back down to the slums the next — rings of a certain existential stagnation, one typical of Can Xue’s writing in the way it seems to adhere to an obscure logic and symbolism.

It’s no surprise that Can Xue’s stories often read like baroque sublimations of buried trauma, as though obscure torments and sorrows were being worked through a misty pane of tertiary symbolism. Can Xue, whose real name is Deng Xiaohua, has made standard practice of referring to herself in the third person, treating her nom de plume as an avatar of sorts, a being apart — a move that becomes a little more comprehensible in light of Can Xue’s personal history. Her father, a newspaper publisher, was sent to the countryside as part of the Anti-Rightist Campaign of the late 1950s; eventually, Can Xue’s family was forced to relocate to the outskirts of the city of Changsha. Later, her mother and two of her brothers would be sent to labor camps in the countryside. As a consequence of these displacements, Can Xue received no formal education after primary school; it was only in the early 1980s, while working as a tailor with her husband that Can Xue began to write her first stories.

As a result, everything in Can Xue’s fictional world is constantly in circulation. The sense of place is abstracted, moving from town to factory to various distant, liminal villages. At times, her characters’ divagations approach a sort of postmodern wandering through a grammatically flensed landscape. The dreamy aspects of her fiction — the lack of solidity of place and psychology, the wispiness of plot, her books reading at times like mercurial picaresques — are nevertheless often tethered to particular thematic concerns. In her novel Love in the New Millennium, for instance, the compression of distance characteristic of the dream state serves as a mirror of the apparatuses of the surveillance state, while the freewheeling interactions between her characters in the border town at the center of her novel Frontier model a utopian vision of pure circulation, one in which human beings, liberated from the depredations of the industrial state, are free to pursue their most errant whims.

Critical discussions of Xue’s work almost always end up describing it as logical, and while it’s true that the stories collected in I Live in the Slums often resemble Kafka’s in their tendency to stem from a demented commitment to the rigorous fleshing-out of a premise, they’re logical in a more straightforward sense as well, relying for their structure on a set cast of dialectics: above and below; dryness and dampness; shadow and light; wasteland and garden; frontier and interior; city and village; paradise and hell. The generative disjunct between these pairings propels Can Xue’s plots, so that each story becomes a little machine of contraries, liberated by its devotion to the second-order logic of oppositions. If logic, for Kafka, was fundamentally claustrophobic, an exitless loop trending downward into subjugation, for Can Xue it’s liberating; it sends her characters out wandering, pinging between fresh absurdities, becoming, finally, a means of expanding the self.

In “Story of the Slums,” the dialectic emerges to push the plot persistently downward. Above the slum lies a nebulous city where absolute sunlight reigns. “The outer walls of buildings were made of glass, and the roofs were metal,” the narrator explains. “When the sun shone on them, it was like fire.” The people living in these transparent houses have themselves become see-through and glassy, their innards visible through the skin. The city’s fierce glare drives the narrator away, and the plot likewise rebounds, leaping down into the tunnels beneath the slum, where the narrator encounters “many little critters […] grubbing around, chiseling endlessly,” and “three people were sitting among them, doing absolutely nothing.” It reads like a scene torn from the pages of the Inferno, and in fact Can Xue’s affinities with the Florentine are real and documented — in addition to her fiction, Can Xue’s written extended literary criticism on Dante, Borges, and Kafka. But there’s a certain flow to her work that feels distinct; if Dante had abandoned the rigidity of his ficta loca — his imaginary places — and allowed his divagations to be guided by the almost clockwork propulsions of the dialectic, you’d have something like a Can Xue story.

In the end, “Story of the Slums” remains elusive, a carnivalesque scroll of happenstance and surrealism, its plot and purpose impossible to classify. Is the novella meant to be an allegory about urbanization and those left behind in a rapidly industrializing China? A parable about the descent of the soul through the muck of the world? Or something purer still — a Beckettian ramble through the fragments of an enervated modernity? There’s a critical tendency to view Can Xue’s stories as oblique commentaries on life in contemporary China, and admittedly they do gesture at contemporary issues: the specter of global warming threatens her characters in the form of biblical floods, while factories and cotton mills loom at the margins of her fictions, the remnants of a superannuated world. However, in general her stories speak to a broader contemporary phenomenon, the profound longing for home.

Can Xue’s characters are constantly returning to their hometowns, whether in person or thought, and the narrator of “Story of the Slums” is no exception. “I still remembered my parents and ancestors,” the narrator recalls. “And I remembered my hometown — that pasture and even the pool in the middle of the pasture.” There’s a connection, here, to a vaguely pre-industrial ideal of pastoralism, of life conducted in harmony with nature, but Can Xue’s concerns aren’t really as simple as pining after a vanished world. Instead, she seems to be asserting that the condition of this longing, at least for the foreseeable future, will constitute an important part of the modern Chinese psyche, that the dialectic of country and city will continue to pulse somewhere deep in the chambers of the heart.

Stories like “Her Old Home” seem to glance at the impact of rapid urban development in China. Having sold her bungalow in the city to live in “an old apartment building in the distant suburbs–the living quarters for workers at a tire factory,” Zhou Yizhen returns to her old home and finds that an old acquaintance named Zhu Mei has taken up her former life down to the very last detail. At the story’s close, a nonplussed Zhou Yizhen departs from the town, divested of her desire to ever visit it again. By fully recreating Zhou Yizhen’s lost life in the form of Zhu Mei’s pantomime, Can Xue plays meaningfully with the question of nostalgia and what precisely it is that we mourn when we miss a particular time and place, showing that it’s not a vanished way of life we grieve, but specifically our vanished life — a singular vision of the world wrapped up ineluctably with our particular self. Otherwise, of course, it would suffice for another person to take up that life, and to lead it in our absence.

The tethering of identity to place is one of Can Xue’s great themes, which she plays with endlessly. Consequently, physical displacement frequently emerges in her stories as a plot device, a way of shifting locales swiftly and disorienting her characters. “Catfish Pit” is an extended farewell to the eponymous neighborhood, spliced with surreal vignettes, as Woman Wang, old and single and childless, is being forced to move out of the neighborhood “in the downtown area packed with old two-story wooden dwellings.” Unsurprisingly, given Can Xue’s own family history of dislocation and the stratagems of uprootedness that were so central to the Cultural Revolution’s project of reeducation, her fictional displacements are often marked with an air of quiet sorrow, a uniquely consistent emotional groundnote, above which the surreal variations of her plots play like an off-kilter melody.

One of the collection’s mistiest stories, “Shadow People,” examines the inhabitants of Fire City, who long ago moved inside to escape the blazing sun; over time, they gradually “became thin, and then even thinner, until they turned into shapes like flagpoles.” Now they take up no space at all. The story has the air of a dark fable, a literalization of the narrator’s youthful desire to fit in — berated by the shadows, he’s constantly yelled at for “occupying space.” As the story progresses, the narrator begins to sound more and more like an initiate to an obscure ascetic rite:

At this moment, I so much wanted to be transformed into one of the Shadow People. I really admired these guys who swayed to and fro. Even their sadness was sublime. If I died some day and became a nut-brown strip hanging on the wall and thus didn’t occupy any space, how wonderful that would be! I remembered that in my childhood, when the southern snowflakes floated to the adobe wall of our home, the wall’s color deepened and the snowflakes disappeared. The fire which heated the house of course also warmed the adobe walls.

The tone of the narration is often innocent like this, with a youthful, starry-eyed aspect. Her characters seem always to be experiencing the world afresh, ingénues to reality. There’s rarely any hopelessness in a Can Xue story, rarely any angst; it’s this subtle disjunct between subject matter and tone that gives her stories their unexpected lightsomeness.

The collection’s final story, “Venus,” follows Qiu Yiping, a middle school student, and her infatuation with her 35-year-old cousin Xuwu, “a scientist researching hot air balloons.” Melancholic and frolicsome à la Calvino, the story’s ethereality and minimalist use of detail lend its scenes of flight a ghostly lucidity, like the curiously crisp images found in old viewfinders. Xuwu, dressed in a blue-and-white-striped sailor shirt, circles a nearby mountain in his balloon. High above the world, he spies Venus, so close he could touch her, so near, he admits to Yiping, that he plans to step out of the balloon and be with her. He enlists his cousin’s help to man the balloon on his next mission but backs out of their plan at the last minute. Instead, he goes soaring over the nearby town, recalling his familial connections with it, all of the ancient ancestors and kindly relatives who link him, inextricably, to the earth.

Though Xuwu eventually disappears over the horizon, Yiping hears his voice ringing out clearly, as though he were speaking directly into her ear. “Venus” feels like a fitting end to the collection, filled as it is with Can Xue’s wonted interests and themes: the vaguely lovelorn attachment to one’s own spatial past; the truncation of distance as a way of disrupting narrative logic; the affirmation, despite the surreal reticulations of the plot, of a basic attachment to the world and the life of the soul. After all, there’s something inescapably cosmic about her writing: the grandness of her vision, the abstraction of her thought, the way the details of lived reality seem to shrink and assume an equal significance, as though one were orbiting a distant star and peering down at the strangeness of an insignificant world.

¤

LARB Contributor

Bailey Trela is a writer in New York whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, The Paris Review, Commonweal, The Baffler, the Cleveland Review of Books, and elsewhere.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Dante’s Psychological Comedy

D. M. Black finds psychological depth in Dante’s “Comedy” and shares excerpts from his translation of “Purgatorio.”

Hong Sang-soo’s Dream Time

On Hong Sang-soo's "The Day After" and the filmmaker's place in slow cinema.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!