In a Life I Never Had I Was a Brave Cosmonaut: On Nona Fernández’s “Voyager”

Claire Calderón reviews Nona Fernández’s “Voyager: Constellations of Memory,” translated by Natasha Wimmer.

By Claire CalderónMarch 8, 2023

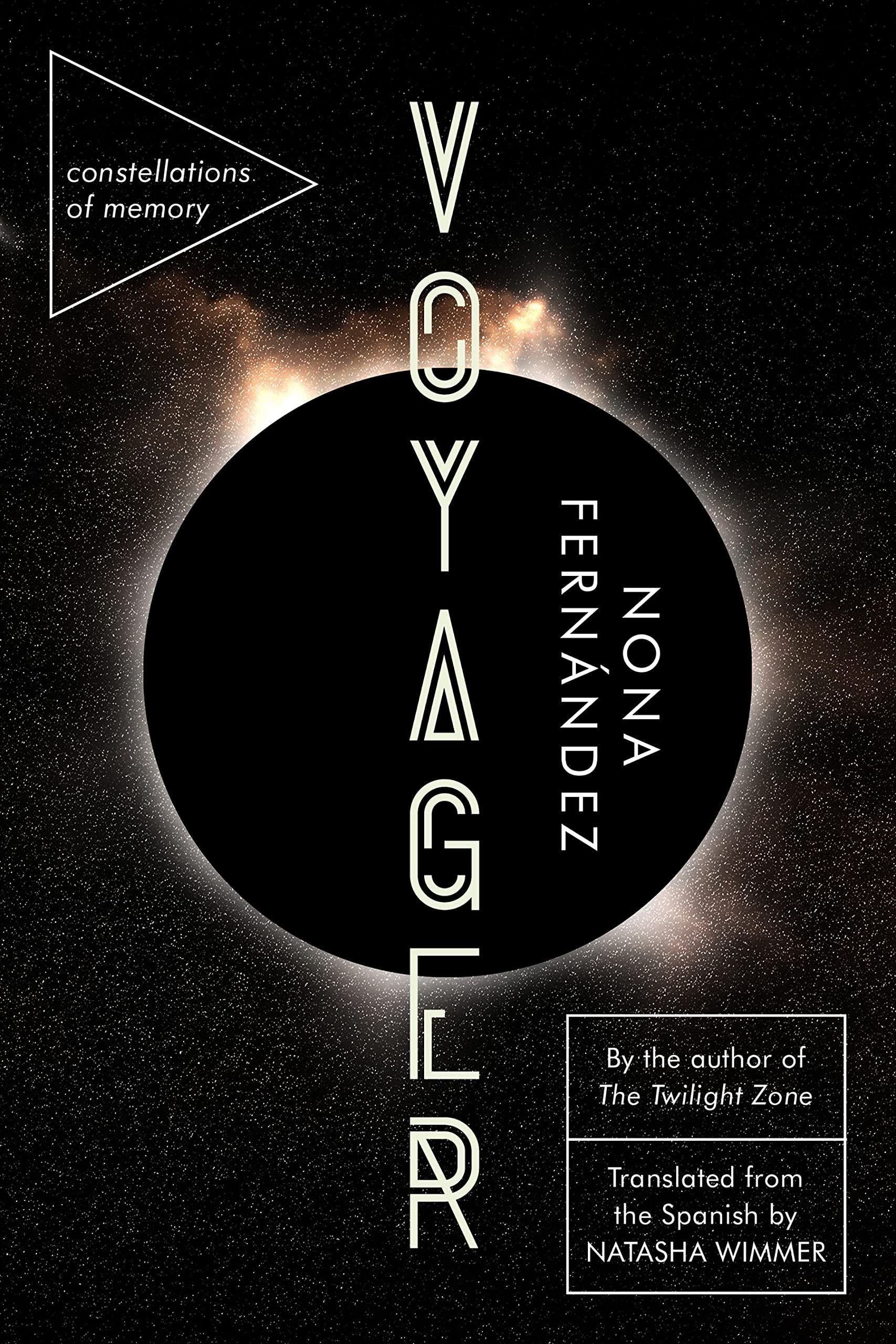

Voyager: Constellations of Memory by Nona Fernández. Graywolf Press. 136 pages.

“IN A LIFE I never had I was a brave cosmonaut and I navigated the stars I’d always watched curiously.” From the opening pages of her 2019 memoir Voyager: Constellations of Memory, Nona Fernández spurns the conventions of the form, opting instead for a wider, more visionary lens. As Fernández accompanies her mother to the doctor after a string of mysterious fainting spells, the scan of her mother’s brain illuminated on the hospital monitor prompts a starscape to spring to life in Fernández’s mind, initiating the book’s voyage through space, memory, and imagination.

Voyager (released in English this year) is the third of Fernández’s books to be translated from Spanish by Natasha Wimmer and published by Graywolf Press. The memoir takes its name from the two exploratory robotic probes launched by NASA in 1977 to observe and record the outer planets of the solar system. True to its title, this book-length autobiographical essay reads like a literary time capsule, in which Fernández herself, reckoning with her aging mother’s illness, embarks on a mission to capture essential memories before their inevitable disappearance.

“Life is ephemeral, but our records remain,” she told me in an interview last month. “Just as stars are born from the material of other dead stars, humanity has been building on the archives that each generation has left behind.” The archivist sensibilities of the Chilean actress, playwright, and novelist are nothing new. They were central to her 2016 novel The Twilight Zone, which won her the Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Prize, and which was later a finalist for the National Book Award for Wimmer’s 2021 translation. In fact, though Voyager is her first explicitly autobiographical book, it covers much terrain that is similar to that of her fiction. Born in 1971, just two years before the military coup that launched a 16-year dictatorship under Augusto Pinochet, Fernández has built a body of work that probes the central paradox of the era: a violence so omnipresent that it became routine and yet was rarely acknowledged, rendering it both visible and invisible, everywhere and nowhere.

The structure of Voyager mimics an interstellar journey across time and space, in which the reader visits and later revisits crucial moments in Fernández’s own memory and that of her country. In precise yet elegant prose that shirks melodrama, Fernández renders crisp and lingering images that orient us to the changing surroundings of the book’s steady orbit. The smell of birthday candle smoke, two fish tied together by their tails, a stiff neck from long stretches of gazing at the starry desert sky—these repeating images function like flash cards, triggering instant associations whose meanings deepen the longer we cycle through them.

Carl Sagan’s television show Cosmos offered Fernández a welcome escape from reality in her youth, transporting her to an alternate universe in the sky. She recreates that same sense of wonder on the page by interweaving narrative with philosophical musings on astronomy, astrology, neuroscience, and memory. She circumvents the oversentimentality that is so often the downfall of stories about family and memory, by constructing a scope that expands and contracts like breath in the body, zooming way in to examine the familiar faces in an old shoebox containing her mother’s photograph collection, then zooming way out to explore the constellations of the zodiac.

But it’s the episodically unfolding sections titled “www.constelaciondeloscaidos.cl,” a now-defunct URL that Fernández refers to as “a dead star whose light has yet to reach us,” that serves as the book’s true motor. In these sections, Fernández chronicles her involvement with an Amnesty International project dedicated to renaming a constellation in honor of the 26 political prisoners executed by the military regime in the Atacama Desert. We learn that she has been appointed the symbolic godmother of a star named for one of those victims, Mario Argüelles Toro; Fernández is helping to organize an event to inaugurate the constellation in the small desert town of Calama, where fragments of the victims’ bodies were found. Suddenly, the cultural and historical weight of her preoccupation with the fragility of memory comes into clear and compelling focus.

Like the way the brain of someone experiencing a traumatic event suspends time temporarily by seeking refuge in the imagination, Fernández periodically grants the reader brief moments of reprieve from the horror at the story’s center through imaginative detours that explore the possibilities of what could have been. For instance, when Fernández arrives at the home Mario once shared with his now 80-year-old widow, Violeta, who has since dedicated her life to searching for his remains in the desert, the writer speculates: “In a parallel life that Mario never lived, maybe he would come out, shushing the dogs barking at me through the bars. He would be seventy-nine, looking different than he did in the picture I found on the internet.”

Whenever I’m grieving a loss, I reach for a poem by Gabriela Mistral called “La Abandonada.” There’s something deeply satisfying about how extravagantly its narrator, grappling with a fresh heartbreak, indulges in her own grief, determined to feel its full weight: “Everything is left over and I’m left over / like a party dress for an unthrown party.” As the poem goes on, the narrator grows increasingly desperate to forget, to destroy all evidence of a once divine life now suddenly and inexplicably gone. Forgetting is an understandable instinct, especially when sought as a reprieve from the grief of the relentless state violence that was a trademark of Chile’s dictatorship. But what is at stake when we forget? When our core memories, the substance of what we have lived, disappear into what Fernández calls a “space-time parenthesis”?

As Fernández and her fellow event organizers drive further into the desert, so too are we propelled deeper into the emotional core of the book. “The screams, the shots, the rattle of the machine guns,” Fernández writes, “These are sounds from long ago. I’d rather not hear them, but they’re still here, lurking in these empty hills, and there’s no escaping them.” Here, Fernández fights against the temptation to forget, bearing witness to the felt presence of old atrocities that continue to reverberate across the landscape. Despite the military’s efforts to conceal evidence of the crimes by exhuming the remains from this site and transferring them to another secret location, she shows us that hidden horrors, vanished as though into black holes or space-time parentheses, never cease to haunt us—just as black holes themselves, although deceptively invisible, are extremely dense, tightly packed with matter rather than vacant.

On the next leg of her interstellar journey, Fernández lands at a new point in the past: October 5, 1988, the date of the national plebiscite to determine whether Pinochet’s self-appointed presidency was to continue. Fernández was only 17 then, and thus ineligible to vote, but she recalls the nervous anticipation in her household as her mother and grandmother prepared to cast their ballots, as well as the conversations among friends dubious that the regime would ever willingly relinquish their power.

Jumping 30 years into the future, we’re introduced to Fernández’s teenage son, also 17, who is preparing a speech on behalf of his school’s student council to commemorate that October day, when the results of the plebiscite paved the way for the official end of the dictatorship and the country’s subsequent “return to democracy.” Learning that his speech has been flagged as offensive by his history teachers, who urge him to omit certain sentences that allude to the dictatorship’s lingering terror rather than declare it neatly resolved, he pushes back. Demonstrating the evident inheritance of her archivist sensibilities, Fernández writes, “[I]t was he and his generation—young people who were being kept in ignorance, forgetful and unquestioning of the past—who would pay for this deed of omission, he said.”

The four years that have elapsed since Voyager’s original publication in Spanish have been monumental ones for Chile. Decades of mounting political unrest erupted in an explosion of nationwide protests calling for, among other demands for systemic change, a new constitution to replace the one penned by Pinochet’s military government. In 2020, approved by a national referendum that took place amidst a global pandemic, a constitutional convention with historic gender parity and Indigenous representation was formed. Two years later, the completed constitution was released to the public. But despite the people’s movement that championed its vision of economic equality, environmental justice, and native sovereignty, the fall 2022 referendum to ratify the constitution failed to pass. Watching from afar, I reached for the dog-eared pages of “La Abandonada.”

I asked Fernández, an outspoken proponent of the campaign for its approval, what she thinks will become of the new, unadopted constitution that, like a party dress for an unthrown party, symbolizes hopeful plans for a future never realized. “I would like to believe that [it] is a constitution of the future,” she said, “written for tomorrow. An inheritance that perhaps someone will pick up and implement when Chile is different and is prepared to think more democratically, more affectionately.”

This is the precise sentiment of Voyager’s final page—returning for a final time to the desert and craning her neck as she gazes skyward, Fernández speculates on what might become of a family photograph from her mother’s 80th birthday if she were to launch it, along with the rest of the archive she has just created, into the vastness of space: “[M]aybe someday, in some other life, in a future I will never know, someone will find it and choose to pick up the baton of memory.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Claire Calderón is an Oakland-based writer and reader with a fondness for stories from the fringes. She is at work on her debut novel, Tomato Skin, a speculative biography about her Chilean bisabuela’s life in the shadows.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Sexual Transcription: On Jen Beagin’s “Big Swiss”

Madeleine Connors reviews Jen Beagin’s new novel “Big Swiss.”

Fracture and Assembly: On Lizzie Borden’s “Regrouping”

Laura Nelson reviews Lizzie Borden’s “Regrouping.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!