“I’m Sure You Understand”: On Pavel Lembersky’s “The Death of Samusis, and Other Stories”

Ian Ross Singleton finds living color in “The Death of Samusis, and Other Stories” by Pavel Lembersky.

By Ian Ross SingletonJanuary 10, 2021

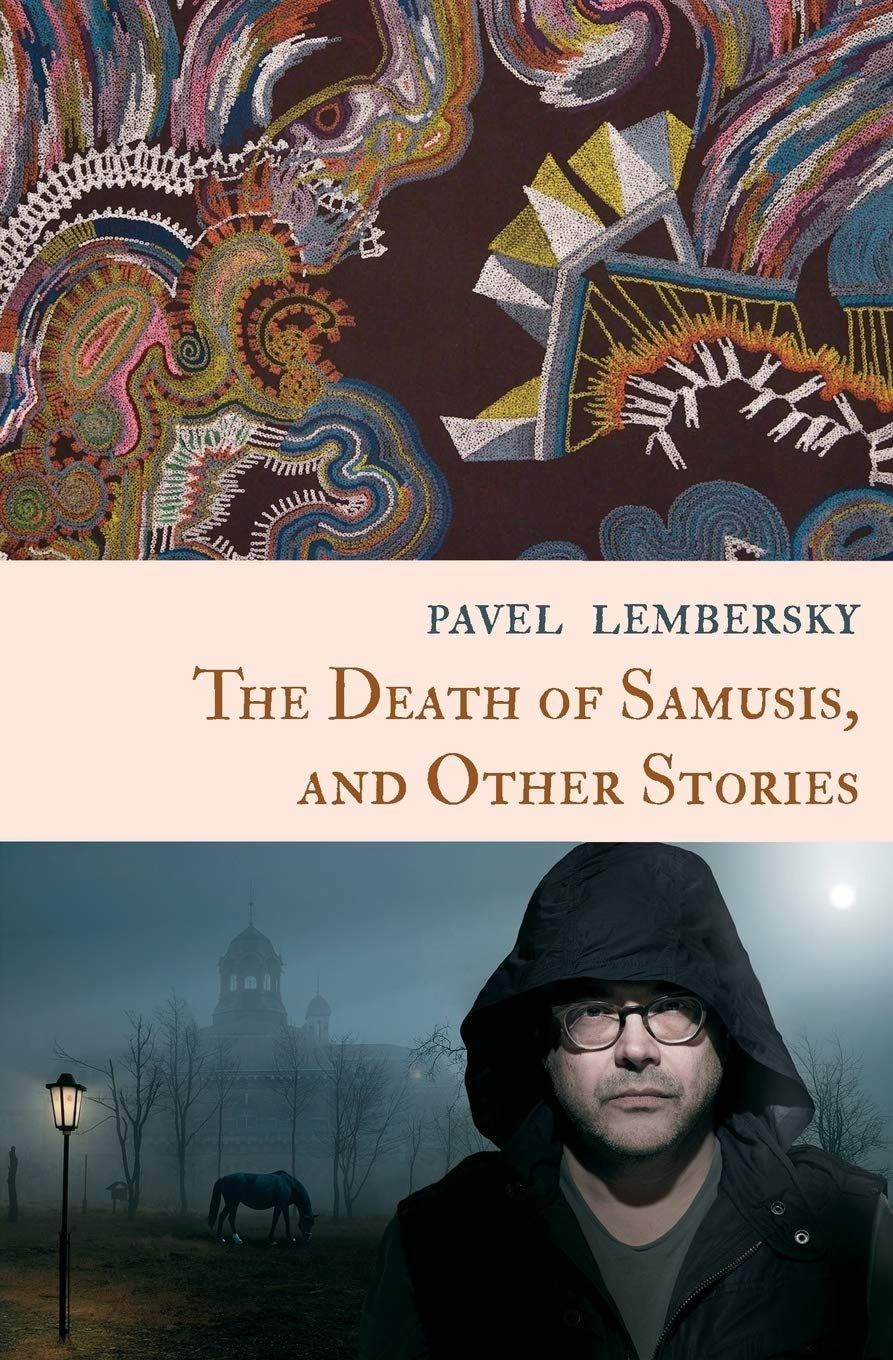

The Death of Samusis, and Other Stories by Pavel Lembersky. M-Graphics Publishing. 162 pages.

PAVEL LEMBERSKY LIVES between two languages. His short stories, originally written in Russian and brought into English through the deft work of translators such as Jane Miller, Sergey Levchin, Alex Cigale, Ross Ufberg, Kerry Philben, Lydia Bryans, and the author himself, appeared last year in a collection titled The Death of Samusis, and Other Stories. Like Lembersky himself, almost all of the characters in Samusis are Soviet immigrants, many of whom pepper their English with Russian words or their Russian with English. Theirs is a hybrid experience, double-sided, and, as a result, Samusis is rife with innuendo.

The first story is a paragraph-long short-short. The title, “Humble Beginnings,” is unpacked in the line: “Humble beginnings, you might call my formative years. I call it child abuse.” This punch line invokes the severity of the author’s native Soviet culture, but with a curious twist. What “you” would use “humble beginnings” as a euphemism for child abuse? Perhaps a reader who takes a sentimental view of Soviet life.

The story goes on to use untranslated (“Humble Beginnings” is the only story without attribution of a translator) Russian words such as koromyslo (a shoulder yoke), borne while doing pushups, and prodrazverstka (Russian Civil War–era food requisitioning that caused famine), which in themselves capture the inseparable link between personal and societal hardship. The author’s use of these untranslated words suggests that the “you” knows Russian in addition to English. The last word of the story addresses the “you” as tovarichi (comrades).

But Lembersky’s “you,” his reader, changes. In “Tony + Lyuda = Love,” the narrator feels compelled to explain, in a teasing tone, fairly common historical knowledge:

Lyudmila and Tony didn’t have much time, I’m sure you understand, for such extended preliminaries: in two days, she would have to return home to Leningrad; that’s what Saint Petersburg was called under the Bolsheviks. And her manner of speech, I’m sure you understand, was more British than American.

Wouldn’t a reader who knows that a Soviet citizen was more likely to learn British English, rather than American also know that Leningrad and St. Petersburg are the same town? The effect of these intimate addresses and asides is, in fact, radically destabilizing, placing the “you” between two cultural stools, where most of the characters have also landed.

Lembersky innuendoes go hand-in-hand with another mainstay of oral storytelling, hearsay. Each of the stories in this collection by a writer born in Odessa, Ukraine, begin the way Isaac Babel’s Odessa Stories do, the way an Odessan anecdote does. “Among the Stones” starts with: “One man, far from old yet, loved to converse with plants. Another one, contradicting the first, found stones to be the more interesting companions. And that is from whom he had alleged to have heard the following story.” Readers might get the feeling that they’re at the end of a long game of telephone, in the process of which a perfectly ordinary occurrence has been inflated and deformed into something hilariously surreal. This is one of the hallmarks of Odessan humor, from the novels of Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov to the sketches of the recently departed comedian Mikhail Zhvanetsky.

In some of the stories of Samusis, the innuendoes and hearsay reach a frantic pitch. “2 Sisters” is basically a scene in which two sisters are talking about a man. The story within the story begins to devolve on the third page:

I’m screaming like mad — basically, he’s trying to shove his tongue in my mouth — I whack him with the umbrella. Next thing, he pulls this giant you know what I mean out of his backpack, there’s water everywhere, drags me into a doorway, the specials are pretty decent, they brought out the raki, leave it on, like that, and the service is not like Chanterelle, let me tell you, but I’m not proud, just asked if they could bag it, for emotional stability, and that’s without any sort of discursive probing!

Such devolutions and divergences are self-evidently postmodern (“discursive probing”), but they also recall the modernistic theories of Russian formalists like Viktor Shklovsky, who, in turn, worshipped the early modern innovations of Laurence Sterne. There’s more than a bit of Tristram Shandy in the title story. After the beginning, the narrator takes a paragraph to step far from the plot:

What we have here is a more or less standard beginning of a story — the death of the hero, the conflict preceding it […] and here one may already permit a succinct instance of stream of consciousness, a relaxation of the logical chains of causation, etc. However, we are pursuing here somewhat different aims, are we not? We can no longer be wowed by psychological realism, n’est-ce pas? And, truth be told, we already find modernism repulsive.

Similarly, the plot of “Chronicle of a Murder” becomes gradually more secondary to parenthetical innuendoes, little stream-of-consciousness moments when the characters take over narration.

Innuendo, when it’s understood, fosters a connection, a partnership between a joker and their audience. “Nothing but Tights” is about a character who murders his lover because she removed her tights (with which he then strangles her). The story could be a creepy thriller, but, as the narrator says, “Nowadays nobody’s gonna care about ooh a landscape, nobody’s gonna be chasing you around for a story.” Reality provides us with enough plot already: “[W]e get stories bright and early with our coffee, thanks to journals and journalists, and the papers had at least a hundred dead at a Bronx disco fire, seems like disasters all around.” Lembersky is after something more than straight stories can provide: “Instead we have ideas: essences, perceptions, apperceptions.”

Writing about abstractions and periodically referring to literary theorists runs the risk of throwing the reader. Lembersky loads “you” up with dark and absurd subject matter. In “The ’90s,” the narrator pities an immigrant who dies “in a foreign place” while, in her “home port,” her ex-compatriots are peeing on a corpse. “She left all this for some ‘abroad’?” the narrator asks. In “Love Gone South,” the narrator interjects, “Why don’t you answer me? Take your time, think about it, then answer me. Accuracy is more important than speed, at least in this instance.” Lembersky won’t leave “you” behind, and he’ll remind “you” of the way of all flesh.

In “Once in a Lifetime,” the narrator states, “I write from nature, but more colorfully than it is in reality, with compositional excesses and telling it all aslant, and then also to be able to sell it to the market. I write so that you may be able to live easier afterward, when neither I nor death any longer (almost) exist.” Is this “color” the Odessan kolorit, a dash of artistic flavoring that can enliven gray Soviet existence or relieve immigrant malaise? Lembersky’s kolorit is not only aesthetic. It’s a means of survival in the face of cultural bifurcation — a way to create a new, perhaps even a somewhat beautiful truth from what could be called humble beginnings, but also child abuse.

¤

Ian Ross Singleton is a writer, translator, and professor of Writing at Baruch College.

LARB Contributor

Ian Ross Singleton is author of the novel Two Big Differences (MGraphics). He teaches writing at Baruch College and Fordham University. His short stories, translations, reviews, and essays have appeared in journals such as Saint Ann’s Review, Cafe Review, New Madrid, Asymptote, Ploughshares, and Fiction Writers Review.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“Chorela” Quarantine (Odessa, 1975)

A Hungarian scholar of Russian literature looks back on her experience in quarantine under Soviet rule.

Go Home and Keep Going: On David Bezmozgis’s “Immigrant City”

Ian Ross Singleton dwells in “Immigrant City,” the latest collection of stories by David Bezmozgis.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!