How Do We Proceed with Our Own Internal Conflict?: On the Translation of Mihail Sebastian’s “For Two Thousand Years”

Julia Elsky reviews Mihail Sebastian's 1934 novel "For Two Thousand Years."

By Julia ElskyOctober 18, 2017

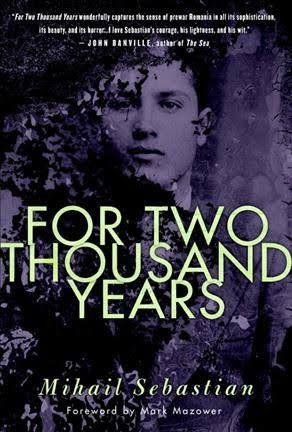

For Two Thousand Years by Mihail Sebastian. Other Press. 256 pages.

IN THE DAYS following the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, Matthew Heimbach, one of the most prominent neo-Nazis in the United States, came out to the local courthouse to support James Alex Fields Jr. He wore a T-shirt with a portrait of Corneliu Codreanu, founder of the Romanian fascist Iron Guard. Most Americans will not be familiar with Codreanu or even the Iron Guard. In Mihail Sebastian’s subtle novel For Two Thousand Years, first published in Romania in 1934, Sebastian chronicles the rise of Codreanu’s movement and presents us with a nuanced view of the individual caught in a time of radicalization and rising xenophobia. Philip Ó Ceallaigh’s fluid translation of the novel comes to us at the right moment.

For Two Thousand Years is a semi-autobiographical fictional diary by the Romanian Jewish writer Mihail Sebastian (pseudonym of Iosif Hechter). It is also a roman à clef based closely on Sebastian’s experiences and relationships in interwar Bucharest. The diarist, who is never named, draws us into his struggle as a Jewish intellectual during the rise of fascism. The absence of a name has the effect of both associating him with Sebastian as well as placing him in the role of an everyman Jewish Romanian. The diary is divided into six parts, or six notebooks, each kept during crucial periods of his life over the course of a decade starting in 1922. We follow him from his studies in law and then architecture at the University of Bucharest, through his architectural work that brings him to the oil fields of Uioara, the cafes of Paris, and once more back again to growing unrest in Bucharest. But Sebastian’s nuanced novel does not simply decry Romanian history as another, inevitable episode in a 2,000-year-old cycle of anti-Semitic violence. The strength and timeliness of this novel lie in the diarist’s grappling with how to respond as an individual to what we now call hate speech and to violence on the university campus.

Sebastian himself recorded in his own journals the rise of the Iron Guard and the heady atmosphere of intellectual life in interwar Bucharest. He lived through a period of great debate about nation-building as Romania more than doubled in size after World War I, incorporating Transylvania, Bukovina, and Bessarabia. Greater Romania now had a population of 30 percent ethnic minorities, including Hungarians, Germans, Ukrainians, Russians, and Jews. The 1923 constitution granted civil rights to these new minority populations and emancipated the Jews of Romania. It was a time of reform and of major expansion in universities and other cultural institutions. In Sebastian’s diaries, like in his novel For Two Thousand Years, we also read of the rise of nationalism and the xenophobic and anti-Semitic movement of proto-fascist students of the 1920s who viewed Jews as invading foreigners. This movement gave way to the rise of the Iron Guard in the 1930s, a fascist movement with a particular spiritual ideology demanding racial and Christian regeneration of Romania through violence. Sebastian, a lucid raconteur of these years, was tragically killed when he was hit by a truck as he crossed the road in 1945, on the way to give his first university lecture. His diaries have been translated into English, and make an illuminating companion to the fictional diary For Two Thousand Years.

The novel opens with the days leading up to and following the December 10, 1922, riots by nationalist students at the University of Bucharest, at a time when the university was an increasingly important site for ideological debates about the nation. The unnamed diarist faces constant beatings at the Faculty of Law. The violence is at first surreal. A student sitting next to him “barks the command” to leave, he exits, and then: “It all happens decorously, ritually. Someone by the door lashes out with his fist, but it is a glancing blow.” He is numb when he leaves, noticing an empty carriage passing by and the cold December air. “Everything is as it ought to be.” The sentences are short here, evoking the student’s startled emotions without any sentimentality. In fact the diarist often openly states that he wants to avoid sentimentality, and he does escape that trap successfully. On December 10, his Jewish friends insist on attending their courses on principle. Now the diarist is determined to remain calm even as violent rallying students outnumber him. There is a heart-wrenching internal monologue:

If I cry, I’m lost. Clench your fists, you fool, if necessary, believe yourself to be a hero, pray to God, tell yourself you’re the son of a race of martyrs, yes, yes, tell yourself that, knock your head against the wall, but if you want to be able to look at yourself in the mirror and not die of shame, don’t cry. That’s all I ask of you: don’t cry.

He continues to attend university, even as it is under military occupation. He endures being punched and smacked while trying to enter lecture halls only to be shut out. But the diarist refuses to see himself as a martyr, and is embarrassed by his diary entry of December 10 quoted above. He reluctantly joins ranks with his fellow Jewish students who decide to enter as a unified group. That tactic also fails. He tells himself he will never be a “social revolutionary,” and at the same time feels tremendous ambivalence about being Jewish. He hates the “two thousand years of Talmudism and melancholy” and craves solitude, not knowing if moving out of the dorm he shares with other Jewish students is an act of cowardice or courage.

Over the course of the novel, we are introduced to different characters who present political and cultural movements, none of which are satisfying. Among them are the diarist’s two Jewish friends, the Zionist Sami Winkler and the Marxist S. T. Haim, who have endless arguments. He sees their commitment to their movements as a way of escaping their own turmoil: “It’s not easy to spend days or weeks running from yourself, but it can be done.”

One day the diarist escapes a menacing group on campus by ducking into a classroom. He stumbles into professor Ghiță Bildaru’s lecture and encounters a new philosophy. So shaken that he can only write down the lecture verbatim, the diarist provides us with a new voice within the pages of his notebook. Bildaru discusses in impassioned tones a general crisis in modern society, advocating a return to the soil in a mystical movement that rejects “a civilization based on intelligence.” Later he convinces the young diarist to change his career and choose architecture as a profession that will link him to the land.

The inspiration for the character Bildaru was Sebastian’s own mentor Nae Ionescu. Ionescu became a mentor to the “new generation” of nationalist students, and as he radicalized he joined Codreanu’s fascist Legion. One of the major blows to Sebastian’s relationship with Ionescu was the anti-Semitic preface he wrote to the Romanian edition of For Two Thousand Years in 1934. Ionescu calls the Jews “a foreign body.” He addresses Sebastian by his legal name, Iosif Hechter, conflating the author of the novel with the fictional and anonymous diarist: “You suffer because you are a Jew; you would cease to be a Jew the moment you would no longer suffer.” Sebastian curiously included the preface in the original publication, although it is not printed in the Other Press edition. Sebastian explained his controversial decision in his pamphlet “How I Became a Hooligan” (1935): he had asked for a preface so he must publish it following the “rules of the game”; not publishing it would be tantamount to censure; and finally he went ahead with its publication because the most serious problem was not that the preface appears in print but that it was written at all to begin with. It still seems masochistic to have included the preface. On the other hand, when the reader today encounters it, she can almost hear Sebastian say: “See, this is what I’m up against.”

The diarist’s real point of crisis comes not in the face of the violent mob but when he is confronted with another Jewish man on a train one year after the December riots. He describes a disruption on the train while traveling to his hometown of Brăila:

“Just what I need!” I’d just been congratulating myself on finding such a good seat, on such a day, in the Christmas holiday rush, in a train overrun by students and soldiers heading for the provinces, and behold our Jewish friend, dragging an entire household behind him, opening the door wide to let in the cold air, pushing my suitcase aside, stepping on my toes, flinging his overcoat over mine and then pressing his way on to the bench between myself and my neighbor, begging pardon with his eyes, though no less tenacious for that in his determination to secure a seat, as guaranteed by his ticket, which he held ostentatiously between his fingers.

Everyone smiled at this comical apparition, and I tried to do the same myself, which took a certain effort, as I pitied him for being ridiculous and was at the same time deeply anxious not to appear friendly to him.

Throughout the novel, Sebastian sketches evocative portraits of characters, although this “comical apparition” truly stands out. Our diarist grows ashamed of his response, and goes out of his way to hold a long conversation with the man who turns out to be a vendor of Jewish books named Abraham Sulitzer. But the diarist’s self-identification as a Jew in front of the other passengers is still a punishment: he begins to speak with a Yiddish lilt to his voice “determined to punish myself properly, to redeem my earlier cowardice.” The controversial Russian-born French Jewish writer Irène Némirovsky’s short story “Fraternity” (1937) also takes place on a train and is almost contemporary to Sebastian’s novel. In “Fraternity,” Christian Rabinovitch shares a cabin with a poor Russian Jew with the same last name and protests, maybe too much, that they cannot possibly have anything in common. But in Sebastian’s book, the protagonist forces himself to come to terms with his shame at being Jewish, and with his horror at his own shame. The most important question for the protagonist is: “Let’s presume that the hostility of anti-Semites is, in the end, endurable. But how do we proceed with our own internal conflict?”

Sulitzer’s appearance awakens in the diarist reflections on his own family history and its parallels with Romanian national history. He sets up a binary in the family. On his father’s side, we find Wallachians who have lived in Romania for over a century, who speak Romanian and wear traditional peasant dress. The diarist finds in them a kind of resilience and reserve. His mother’s family is from Bukovina. They are religious, learned in Jewish letters, but also melancholy and weak. I would not call the diarist’s remarks about his mother’s side self-hating but instead they demonstrate the diarist’s angst about the place of Jews in Romania, especially those from the post-1918 territories. The sides of his family represent the “divide between the Danube and the ghetto.” Ó Ceallaigh translates the original Romanian word Neînțelegerea as “divide”; it could also mean a misunderstanding, and that the places are perhaps not permanently separated but divided through confusion or a misconstruction.

After finishing his studies in architecture, the diarist is not any closer to finding the spirit of the Romanian soil, as professor Bildaru thought he would be. His two years in Paris in the early 1930s are also fruitless. In a reversal of typical portrayals of the city of lights as a paradise for intellectual expats, the diarist decides: “Security provides a poor environment for reflection.” He returns home to confront the increasingly tense situation in Bucharest. We see a change in the diarist, from the conflicted university student now to a man who is determined to think clearly. Looking closely at political arguments in Romania does not drag him into despair but rather sets him up as the only character in this novel who is not seeing things in black and white, the only character able to face the gray areas of national identities.

In the final parts of the novel, which take place in the early 1930s, the diarist faces a new wave of anti-Semitism. This time the movement is more concrete and menacing. The ideology he struggles to unpack, and the one he ends up truly fearing, is the nihilism of an acquaintance from his university days, Ștefan Pârlea. Pârlea is based on Sebastian’s friend and the famous philosopher Emil Cioran. The main question for Pârlea is: “[I]s the state at the point of collapse or is it not?” The nihilist explains his position by saying that there is a drought and the country needs rain, so what if it comes with hail, meaning “if the revolution demands a pogrom, then give it a pogrom.” The diarist muses he could have replied: “[A] metaphor is inadequate in the face of a bloodbath.”

Attending Pârlea’s lecture as the audience chants an anti-Semitic song, and hearing cries of “Death to the Yids!” on Boulevard Elisabeta, the diarist senses a coming tragedy.

It is extremely difficult to follow the progressive hardening of enmity from one day to the next. Suddenly you find yourself surrounded on all sides, and have no idea how or when it happened. Scattered minor occurrences, gestures of no great account, the making of casual little threats. An argument in a tram today, a newspaper article tomorrow, a broken window after that. These things seem random, unconnected, frivolous. Then, one fine morning, you feel unable to breathe.

What is even harder to comprehend is that nobody involved in any of this, absolutely nobody, bears any blame.

The diarist has spent his efforts in his diaries avoiding abstraction, and dealing with his own past and unresolved questions about his place in Romania. He is all the more isolated as he bears witness to the refusal of those around him to accept that a person is at the root of each initially inconsequential insult, that the arm that punches you belongs to an individual. Even the mention of the tram brings us back to the diarist’s struggle to come to terms with his Jewish identity in the train car shared with Sulitzer the book vendor. The diarist repeats his long-held desire not to be a martyr. Instead, he will continue to hold his position and to go deeper into his existential quest of what it means to be a Jew and a Romanian. He will go on to make his own personal statement about his position as a Romanian Jewish intellectual by building something new at the darkest moment of his life: a sunlit house with huge windows open to the coming seasons, a bright house he designs for none other than Professor Bildaru.

Sebastian’s text is now available to English speakers through Ó Ceallaigh’s excellent translation. The English text reads fluently, and the translator has pleasingly left traces of the Romanian in the names of places. Boulevard Elisabeta and Calea Victoriei remain, giving us the sense of being on these elegant streets of the Romanian capital. He clarifies that Văcărești, where the diarist’s student dormitory is located, is a Jewish neighborhood. It is an unobtrusive addition that clarifies the importance of this particular location to the reader unfamiliar with Bucharest. Reading Sebastian’s novel and his diaries, you could map out a fascinating tour of the city.

When the diarist tells Sulitzer that a text he lent him was interesting, he realizes interesting is the last thing a reader should ever say about a book. Instead, “A book either knocks you down or raises you up. Otherwise, why pay money for it?” Sebastian’s novel does both.

¤

Julia Elsky is Assistant Professor of French at Loyola University Chicago.

LARB Contributor

Julia Elsky is Assistant Professor of French at Loyola University Chicago.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Heidegger and Anti-Semitism Yet Again: The Correspondence Between the Philosopher and His Brother Fritz Heidegger Exposed

Heidegger’s letters to his brother show him to have been far more committed to National Socialism than his apologists have argued.

The Philosopher of Failure: Emil Cioran’s Heights of Despair

Failure runs through it all, from Cioran’s “On the Heights of Despair” to “The Trouble with Being Born.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!