Horror in Revision: On the Contemporary Gothic

Adam Fales on Ahmed Saadawi’s “Frankenstein in Baghdad,” Sarah Perry’s “Melmoth,” and Chase Berggrun’s “R E D” — emissaries of the “contemporary Gothic.”

By Adam FalesDecember 1, 2018

Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi. Penguin Books. 288 pages.

Melmoth by Sarah Perry. Custom House. 288 pages.

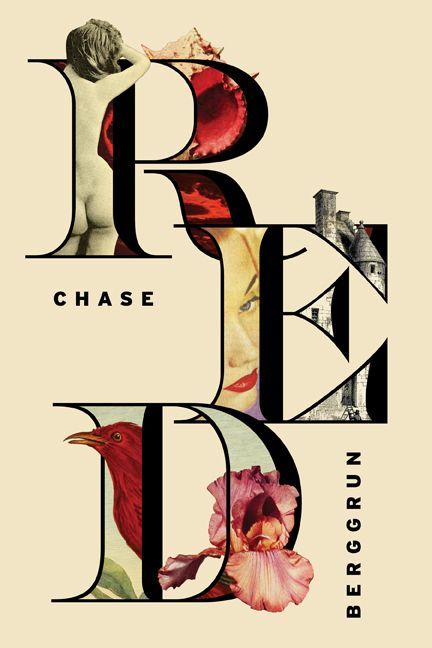

R E D by Chase Berggrun. Birds, LLC. 76 pages.

THE GOTHIC NOVEL occupies a contradictory place in our culture. It is a pleasure both low and high: its cheap thrills have merited significant scholarly consideration. While subject to a persistent misremembering (Frankenstein was the doctor), the genre has also provided some of the most enduring moments and characters in literary history. These sensational novels have frequently burst beyond their literary constraints to spawn film and theater adaptations of varying degrees of faithfulness that have then spawned ever more sequels, parodies, and biographical works.

The fuzziness of its cultural stature is compounded because it is difficult to specify exactly what we mean by the term “Gothic.” The genre often comprises some combination of horror, counterfactual and imaginative historical fiction, repressed sexualities, paranoid narrators, and an abandoned castle or two. Crucially, these novels convey these features through a convoluted narration that unfolds layers of stories within other stories that are almost always expressed as one form of media embedded within another (a love letter transcribes a found manuscript, which is itself a rambling transcription of a story being told to someone).

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, in her 1980 study The Coherence of Gothic Conventions, likens these embedded structures to the Gothic trope of live burial. In Gothic novels, tales that have been textually “buried alive” rise again to impact the story that envelops them. The genre’s interest in materiality, then, has a pervasive influence not only on the kinds of stories told but also on the way these authors tell them.

This latter aspect of Gothic novels — their narrative technique — is a key focus of three recent books that adapt 19th-century British Gothic novels to a contemporary, international context. In Frankenstein in Baghdad (originally published in 2013 and translated into English from the Arabic by Jonathan Wright in 2018), Ahmed Saadawi hacks apart Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) to reconfigure it in the year 2005 in Iraq. For her new book Melmoth, Sarah Perry unearths Charles Robert Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer (1820) and transports it to the Czech Republic in the 21st century. And in her poetry narrative R E D, published in May, Chase Berggrun finds a new story coursing through the veins of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897). These books hardly resemble each other, except in their authors’ shared interest in how the Gothic narrative has changed over time. In diverse ways, Melmoth, Frankenstein in Baghdad, and R E D explore the genre’s materiality both textually and extratextually by updating the plots of these classics while also featuring the books themselves in their plots.

Through their literary investigations, these authors challenge many of the assumptions about history, race, and gender that underlie their Gothic predecessors. They understand the way that history preserves certain stories while precluding others. Beyond merely noting a presence or absence in our historical memory, these authors are interested in describing the visceral and material ways that stories reach our present moment (or, of equal importance, the ways they don’t).

This investigation can occur in a literal archive, as in Perry’s retelling of Melmoth, or it can happen in the wreckage of an explosion on a Baghdad street, as in Saadawi’s Frankenstein in Baghdad. Always it takes place in the words (and the spaces between them) that make up our books, conversations, and questions about history, as Berggrun’s R E D illustrates. These books show how our contemporary moment may be just as “Gothic” as the 19th century of their predecessors. Even as our terrors change, our encounters with them remain remarkably similar. History repeats itself, first as someone else’s fear, then as our own.

Unbearable Creations

Frankenstein dramatizes the dead coming to life. Shelley structures its narration as a frame narrative. In one account, a captain attempts a voyage to the North Pole and encounters a strange man, Victor Frankenstein, who reveals how he discovered and exercised the ability to bring inanimate flesh to life. Frankenstein relates the story of his monstrous creation, which vengefully ruined his master’s life, and includes a vivid recollection of the monster’s story. In it, the creature philosophizes about the nature of creation by engaging with the work of writers such as John Milton. The effects of the monster’s story ripple outward in the frame and impact the progress of Frankenstein’s and the captain’s lives, as all the narrative layers merge into one.

Frankenstein in Baghdad, on the other hand, is a story about how matter moves between states of life and death. Saadawi’s monster is stitched together not by a scientist but by Hadi, the owner of a junk shop who uses bodily remains found on the streets of the city. The “Whatsitsname,” as he calls it, becomes not a source of wonder but an accidental, unmanageable force. Saadawi eschews science and instead populates his book with magic that escapes the notice and comprehension of most of his characters.

In Shelley’s book, the monster philosophizes about the nature of creation, but in Saadawi’s retelling the main issues are justice and guilt. Cleverly redirecting Frankenstein’s monster’s desire to destroy his creator, Saadawi has the Whatsitsname seek revenge on those who killed the prior owners of his body parts. But once the Whatsitsname completes each act of vengeance, the avenged part falls off. As he replaces his lost parts with new pieces, the Whatsitsname multiplies his targets — he must kill both innocent and guilty people to keep himself alive — and finds himself implicated in the criminality that he condemns.

Beyond Hadi and his monster, the novel largely revolves around a young journalist, Mahmoud al-Sawadi, at a magazine called al-Haqiqa (“The Truth”) who gets in over his head as he climbs the ranks of the editorial board. He persuades the Whatsitsname to record his story onto a tape recorder, which mirrors the monster’s story in Shelley’s novel. From this recording Mahmoud publishes a magazine story that references Shelley’s Frankenstein and inadvertently sensationalizes the Whatsitsname. After his prominent but shady publisher Ali Baher al-Saidi leaves town to escape allegations of crimes against the government, Mahmoud finds himself caught up in the investigation run by Brigadier Majid, head of the Tracking and Pursuit Department, a joint force overseen by Iraqi and US military intelligence.

A career military officer, Majid sees his position as an opportunity to make himself indispensable in the event of sudden shifts of power. He does this by indulging the misguided notion of employing a troop of fortune-tellers, card-readers, astrologers, and practitioners of magic. The government report that opens Saadawi’s novel reveals that Majid’s actions have actually harmed his career: “It is clear that the department had been operating outside its area of expertise, which should have been limited to such bureaucratic matters as archiving information and preserving files and documents.”

All this is made more curious by the fact that Majid has no knowledge of magic. Technically in charge of information management, he spends a typical day at the office reading reports that only contain findings that were already predicted and attempting to fire someone who has seen the future and preemptively packed up his desk. This is both the most unusual and the most efficient way to structure a department focused on archiving information: once you can read the future, you can document it before it has even happened.

In the same way, Saadawi’s frame narrative disrupts the tension between future and past to put Frankenstein’s structure to more dissonant ends. Before any characters are introduced, the novel’s opening “Final Report” reveals that Majid’s department will be disbanded and that the following 17-chapter story, written by someone referred to only as “the author,” “should not be published under any circumstances and […] should not be rewritten.” However, two additional chapters provide a metanarrative that explains how the preceding story escaped the government’s control and erasure. The author becomes part of his own story when he buys the tape recorder from Mahmoud and recounts how the government framed Hadi for the string of killings committed by the monster.

In a sense, Frankenstein in Baghdad depicts a conflict between different kinds of media. Saadawi’s novel plays out through government reports, tape recordings, and circulated magazines. In one moment, the monster compares himself to a media device: “I’m like the recorder that journalist gave to my father, the poor junk dealer. And as far as I’m concerned time is like the charge in this battery — not much and not enough.” Here, media’s crucial aspect is its ephemerality. The Whatsitsname draws his power and his terror from the ever-changing nature of his body as he essentially recharges his battery. The analogy to media works both ways. Even official, overarching reports by the US government are subject to revision by comparatively minor forms of documentation such as unpublished novels and local magazines. Saadawi’s monster illustrates the redemptive power of even the most ephemeral material. No matter how far down it is “buried,” it has the potential to rise from the dead and assert its own story.

Unremembered Events

The novel that most exemplifies the Gothic model of multiple embedded narratives is Charles Robert Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer, which follows John Melmoth as he discovers the tale of an ancestor who made a deal with the devil to gain another century and a half of life. Compelled by seeing a 1646 portrait of his near-immortal ancestor and learning that the man is still alive, John tracks the tale of “Melmoth the Traveller,” who goes around the world tempting people to sin so that they might take over his debt to the devil.

The story begins when John inherits an estate and portrait — and by extension the devilish tale — from his uncle. This inheritance makes the past bear viscerally on the present (and, in turn, dictate the future). It traps John in his story. Because they share a surname, he often sees himself in the stories he uncovers of Melmoth’s past, and in this way John’s inheritance becomes a sort of debt that he must set right before he can go on living. The novel resists a straightforward resolution of how the past has unsettled the present. Instead, it closes as John and a friend “[exchange] looks of silent and unutterable horror, and [return] slowly home.”

Something of a sequel to Melmoth the Wanderer, Perry’s novel follows a quiet woman named Helen Franklin as she investigates the enduring myth of an immortal witness named “Melmoth,” a woman in this retelling. Helen’s transhistorical explorations uncover narratives in a variety of forms (one of which is Maturin’s novel) that feature a cryptic, darkly clad woman gradually revealed to be Melmoth, who watches a range of historical scenes of terrible violence that include Nazi Germany and the Armenian Genocide.

Usually, Perry’s narrators are those figures most culpable for violent horror, and this culpability haunts Helen’s own past. While working as a foreign-aid worker in Manila, Helen participated in the suicide of a burn victim in intense and incurable pain. This crime, while compassionate enough from the perspective of Helen and those around her, led to a murder investigation that resulted in Helen’s Filipino lover, Arnel, taking the blame. Perry ties Helen’s story to the other horrific tales that populate Melmoth to critique the way that whiteness imposes itself on foreign countries through aid organizations while still forcing black and brown bodies to suffer the consequences of white actions. As Helen uncovers each story, her cowardice gradually overwhelms her.

In the novel’s most striking moment, Perry explores the material transformation that allows Gothic novels to find readers:

She sits at the desk and takes out the manuscript. That minute copperplate seems already familiar — appears, as she takes her reading glasses from their case, actually to dissolve upon the page, the ink reshaping itself into plainly printed English: sans serif, twelve-point type.

This surreal transformation, in which a handwritten manuscript converts to neatly typed pages, plays with the Gothic novel trope of evoking horror by describing a scrawled manuscript, usually torn and partially illegible. Maturin himself uses it: “The conclusion of this extraordinary manuscript was in such a state, that, in fifteen mouldy and crumbling pages, Melmoth could hardly make out that number of lines.”

Maturin deliberately sets this in terrifying contrast to the genteel experience of reading a bound novel (such as Melmoth the Wanderer), while Perry depicts Helen’s Gothic manuscript becoming gradually more legible to highlight its similarity to a modern book like Perry’s.

Epistolary novels unfold their plots through letters and diaries too, but Gothic novels uniquely use representations of reading’s materiality — supernatural, haggard documents discovered in scary places — as tools to frighten readers. Perry twists this tactic by having characters stumble onto terror in neatly typed and ordered documents such as government reports and books set in 12-point type. This becomes painfully apparent in an embedded story about the bureaucratic horrors that allowed the Armenian Genocide. One of Perry’s characters says, “Did you see what you have done, with your letters and documents? What great things you can accomplish from behind a wooden desk with three drawers, and a filing cabinet kept in good order!”

While the Gothic novel feeds on the materiality of horror, Perry’s approach emphasizes the absurdity that a material as innocuous and commonplace as paper can convey the world’s most unspeakable horrors. In the process, Perry does not distinguish her readers’ experience from her characters’ as Maturin does with his “mouldy and crumbling pages,” and instead implicates her readers by framing their experience as similar to Helen’s.

Through this exploration of materiality, Perry uses her novel’s conclusion to transform the reader’s interpretation of Melmoth. The woman who has thus far been a supernatural villain becomes a sacrificial hero willing to remember the horrifying history that others wish to forget. Beckoning them to join her acts of witnessing, Melmoth pivots and speaks directly to the reader: “Oh my friend, my darling — won’t you take my hand? I’ve been so lonely!” This final moment retroactively rewrites Perry’s novel, as the reader is asked to weigh the repeated horrified responses to Melmoth against her final apostrophe and must reconsider her from a tender and sympathetic angle. The author positions the reader as just another character unsure of the stakes and consequences of taking Melmoth’s hand.

Maturin and Perry both embed fictional stories, but Perry enriches our sense of reading’s materiality. She explores how stories change and live in time, and, in the process, disrupt the other stories of which they become a part. While Shelley’s and Saadawi’s Frankensteins focus on bringing dead bodies to life, Perry’s Melmoth investigates how authors animate stories by, paradoxically, burying them in other narratives. Whereas Maturin’s stories beg to be hidden, Perry’s tales are dying to be unearthed.

Unspeakable Silences

Bram Stoker’s Dracula is, similarly, a story that is just as much about the media that conveys its narrative as it is about the narrative itself. The story follows a group of loose associates brought together to prevent the terrifying Count Dracula from spreading his vampiric disease in London. Stoker depicts a range of characters, including Jonathan Harker, Mina Murray, Lucy Westenra, John Seward, and the enigmatic Dr. Van Helsing, using media as diverse as shorthand diaries, letters, newspaper articles, and phonograph recordings.

This flurry of material becomes integral to the book’s plot. Near its climax, Mina begins the arduous work of collating this media to prepare for the battle with Dracula: “In this matter dates are everything, and I think that if we get all our material ready, and have every item put in chronological order, we shall have done much.” A large portion of the novel’s latter part entails this information management, as private diaries and letters become shared documents and the characters establish a shared experience through the media they created.

In R E D, Chase Berggrun deconstructs Stoker’s tale in a series of erasure poems and uncovers a new narrative embedded in the text. Berggrun first explains the poems’ creation in a short “Note on Process”: “[T]ext was erased while preserving the word order of the original source, with no words altered or added, according to a strict set of self-imposed rules […] a new story is told, in which its narrator takes back the agency stolen from her predecessors.” Berggrun links the structure of these poems to her own gender transition: “As they were discovering and attempting to define their own womanhood, the narrator of these poems traveled alongside them.”

Berggrun’s prefatory note offers a revisionist analogue to Stoker’s preliminary fictional statement, which establishes the provenance of Dracula’s documentary narration:

How these papers have been placed in sequence will be made clear in the reading of them […] There is throughout no statement of past events wherein memory may err, for all the records chosen are exactly contemporary, given from the standpoints and within the range of knowledge of those who made them.

While this note thickens the sense of facticity that dramatizes Dracula, its impersonal tone adds a layer of irony since the reader gradually learns that all these documents were in fact compiled by Mina, the ill-treated heroine whose feminized labor essentially saves the lives of most of the characters. In a different way, Berggrun’s preface brilliantly connects fiction to fact by coupling material organization with formal decomposition in a way that both resembles and redirects Mina’s efforts. The narrator of these poems “takes back the agency stolen from her predecessors” by manipulating the text one of those predecessors compiled.

The narrative, formal, and material transformations of Dracula that interest Berggrun unite about halfway through R E D. The unnamed narrator reaches a moment of self-discovery through the act of writing:

I was trying to invent an excuse in a different voice

I gave myself away to my typewriter

I have typed every thought of my heart

My power to tell the other side

I have been touched by a wonderful anguish

I have tried to be useful

I have copied out the words of this terrible story

I contain no secrets

Berggrun’s scene sets up a parallel between Mina’s transcription and her own, as both writers adopt “a different voice” (Mina that of the male characters and Berggrun that of Stoker). In the process, Berggrun modifies the multiple layers of voices in Stoker’s novel to exorcise its misogynist violence. This polyvocal, multimedia approach allows Berggrun to adopt the chorus of voices that make up “this terrible story” and create a new story that affirms, rather than effaces, its narrator’s identity.

Furthermore, Berggrun begins most of her lines with the word “I.” Though in Stoker’s text this pronoun denotes the individual characters narrating his discrete sections, in R E D Berggrun unites this variety of perspectives in one voice. On one hand this unified voice resembles Mina’s copying of multiple perspectives into one account, but on the other it represents the way in which Berggrun’s narrator is forced to adopt identities she wishes to reject. Berggrun’s poems literalize this abuse in the language, as her narrator “copies out” “terrible stories.” What Stoker writes as discrete identities, R E D’s narrator — and, I would argue, Mina — experiences as forced identification that is as urgent to overcome as the vampire that haunts the novel.

The power in Berggrun’s project comes from the form of erasure poetry. Whereas Mina transcribes the words of the men surrounding her, Berggrun’s narrator erases those same words to imagine that Mina could have written her own version instead. Berggrun highlights how agency and desire get worked out in the process of writing, how erasing a past narrative can be a means of reckoning with the way it was constructed. In R E D, Berggrun builds on the material engagements of Frankenstein in Baghdad and Melmoth by confronting the fact that the very act of turning traumatic experiences into words, whether one’s own or another’s, may be the most terrifying — and Gothic — aspect of language.

Undead Reckonings

For all their revisions of the 19th-century Gothic novel, Frankenstein in Baghdad, Melmoth, and R E D utilize structures and innovations that resemble those of the originals. Saadawi evokes the same sense of paranoia that pervades Shelley’s Frankenstein, Perry blends into her text the same mode of historical writing that Maturin layers through Melmoth the Wanderer, and Berggrun uses erasure to mimic the silence that faces “unspeakable” horrors in Dracula. These books, loosely grouped as “contemporary Gothic,” represent an admirable response to an unpleasant aesthetic legacy. All three contemporary authors make a point of explicitly honoring their literary progenitors, but Saadawi, Perry, and Berggrun, with varying levels of specificity, condemn the imperialism, racism, and transmisogyny that shape the work of these predecessors.

In our present moment, it is often unclear what to do with all the confusing, threatening, and insulting information hurled at us. The sheer volume of media input confounds any productive response. Practically the only thing we can’t do is the simplest option: ignore it. Part of the brilliance of Gothic novels is that they synthesize numerous horrors into a compulsively readable text, but, as any Gothic novel protagonist knows, reality inevitably leaves us vulnerable to multiple hauntings at once.

This inability to manage our present motivates authors such as Saadawi, Perry, and Berggrun to turn to the material of our past to conquer present terrors. They show how rewriting — looking at material in a new way, engaging with it on personal terms, finding a whole new story to tell — is a political gesture, and they offer forceful examples of what it means to reshape our undead history. Collectively they articulate the existential dilemma that while media may terrify us, it is also the vehicle of our salvation.

¤

LARB Contributor

Adam Fales is a PhD student at the University of Chicago and Managing Editor at Chicago Review. His writing has appeared in LARB, Public Books, Avidly, and homintern, among other places. You can find him on Twitter @damfales.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Frankenstein Turns 200 and Becomes Required Reading for Scientists

"Frankenstein: Annotated for Scientists, Engineers, and Creators of All Kinds" can remind scientists and engineers to proceed with caution.

The Cost of War: Parts and Labor

Ahmed Saadawi’s novel “Frankenstein in Baghdad” continues to win prizes for good reason: it is one of the best fictional accounts of the Iraq War yet.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!