Giving “Doctor Zhivago” Another Chance

Christine Jacobson celebrates the appearance of Nicolas Pasternak Slater’s faithful yet natural translation of his uncle Boris Pasternak’s “Doctor Zhivago.”

By Christine JacobsonMarch 5, 2020

WHEN MAX HAYWARD and Manya Harari translated Doctor Zhivago into English in 1958, it had not yet appeared in Russian. The novel, which traces the life and love affair of a Moscow doctor through three wars and two revolutions, was considered “anti-revolutionary” by the Politburo, and Soviet publishers had refused to publish it. In response, Boris Pasternak entrusted copies of his manuscript to foreign friends who ensured the novel would be published and read abroad. This Russian literary classic was in fact first printed as Il Dottor Živago in Milan; English and French translations quickly followed. In their translators’ note, Hayward and Harari expressed their wish to see the novel appear in Russian and, eventually, to “fall into the hands of a translator whose talent is equal to that of its author.” This note may sound charmingly self-deprecating to readers, but Hayward and Harari had been given just three months to translate Pasternak’s lengthy text. They were, as they say in their introduction, under no illusions that they had done justice even remotely to the original.

Many decades later, another duo attempted the feat. This second translation was done by the husband-and-wife team Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky for the 50th anniversary of Pasternak’s death in 2010. Unfortunately, justice still eluded Zhivago. While the Hayward-Harrari version has long been criticized for its divergence from Pasternak’s original prose, Pevear and Volokhonsky demonstrated another flaw — slavish devotion to its Russian syntax. Consequently, the novel’s reputation in the West has suffered. Zhivago is now part of Russia’s 11th-grade school curriculum, but many Slavic departments in the West gave up on the novel long ago, siding with Nabokov, who dismissed it as a “clumsy, trivial, and melodramatic” book. Pasternak is often left off the list of Russia’s iconic literary writers such as Gogol, Pushkin, Tolstoy, and Dostoyevsky. (Indeed, his likeness is missing from my nesting doll set of great Russian writers.) I think most Americans would agree that David Lean’s sweeping 1965 film adaptation outpaced the popularity of its source text. And yet, despite it all, the novel has always ranked among my favorites. I can’t resist a text that grapples with themes of love and loss set against the backdrop of the Russian Revolution, and I’m a sucker for thick description of rural Russia. Fortunately for me and for other Pasternak devotees, a new translation by the Russian author’s nephew, Nicolas Pasternak Slater, suggests the day Hayward and Harari wished for has finally come, more than 60 years later.

Pasternak Slater’s translation of the novel succeeds precisely where the previous attempts have failed. He successfully navigates between the Scylla and Charybdis of translation, rendering Pasternak’s text in natural English prose while also remaining faithful to the original tone. The latter was particularly important to Pasternak, a celebrated translator himself. The Russian author doesn’t make an English translator’s job easy — he sometimes favors long, complex sentences that reflect a character’s wandering thoughts or layer lush descriptions of Russian nature. The challenge of tackling these sentences comes on top of problems built into the Russian language. In his translator’s note, Pasternak Slater points out that Russian prose is often rendered in the passive voice while English decidedly prefers the active, and that Russian is fond of pesky abstract nouns that sound pompous to English-speaking ears. Preserving Pasternak’s distinctive prose rhythms while dismantling Russian-sounding constructions is a high-wire act, which Pasternak Slater pulls off with panache. Take this sentence, translated directly from the Russian: “With generous breadth and luxury, the pre-evening hours of the wonderful, clear day delayed, lingered. (Со щедрой широтой и роскошью медлили, задерживались предвечерние часы чудесного, ясного дня.)”

Pasternak Slater rearranges the order of the words, laying them out in a natural yet supple English sentence that preserves the characters’ sense of weightlessness: “It had been a beautiful, clear day, and now, generous and expansive, the late afternoon hours still stretched out luxuriously before them.”

Pasternak Slater’s translation definitively wooed me when I reached my favorite part of the novel. Having not seen Lara Antipova since they served together as medical volunteers in World War I, Yuri Zhivago spots her from across the room in a small-town library on the edge of the Ural Mountains. Several years have passed since he last saw her; the Russian Revolution has driven him and his family from Moscow to his wife Tonya’s former estate near Yuriatin, the town where, unbeknownst to Yuri, Lara lives. As a librarian, I can’t resist the romance of this serendipitous encounter in a library reading room. Unfortunately, the Pevear-Volokhonsky version is confounding:

He saw her almost from behind, her back half turned. She was wearing a light-colored checkered blouse tied with a belt, and was reading eagerly, with self-abandon, as children do, her head slightly inclined towards her right shoulder. Now and then she lapsed into thought, raising her eyes to the ceiling or narrowing them and peering somewhere far ahead of her, and then again, propped on her elbow, her head resting on her hand, in a quick sweeping movement she penciled some notes in her notebook.

This passage raises several questions. How does one see another person “almost from behind”? If Yuri can hardly see her, how can he observe her raising and narrowing her eyes? And why does Lara seem to be pantomiming the act of reading? Hayward and Harari’s version is even more confusing, alleging that Yuri sees her “side-face, almost from the back.” Pasternak Slater makes this scene much clearer:

He could see her profile, half turned away from him. She was wearing a light-coloured check blouse with a belt, and was immersed in what she was reading, oblivious of everything else, like a child. Her head was bent a little to one side, towards her right shoulder. From time to time she looked up at the ceiling, lost in thought, or screwed up her eyes and stared straight ahead; then she would lean her elbows back on the table, prop her head on one hand and copy something down into her notebook with a brisk, sweeping flourish of her pencil.

Doctor Zhivago is a long book. Depending on the translation, it usually clocks in at around 550 pages, and when I read Pevear-Volkhonsky’s version 10 years ago, it felt like a slog. But thanks to Pasternak Slater’s choices, reading the novel becomes a pleasure. This not only evinces Pasternak Slater’s talent, but also underscores Pasternak’s brilliance as a writer. In an article for the Guardian, Pasternak Slater’s sister Ann Pasternak Slater once described their uncle’s prose as “packed, concise, colloquial and muscular.” There’s little evidence of this in Pevear-Volkhonsky’s translation; in Pasternak Slater’s translation, it’s obvious. Nowhere is his packed, concise prose more on display than when Pasternak writes in Lara’s voice. While Zhivago’s thoughts are meandering and expansive, Lara’s are focused and shrewd. Mulling over her abusive relationship with the much older and wealthy Komarovsky, Lara thinks,

What is it that terrifies us — thunder and lightning? No, it’s sidelong glances and whispers. Life is full of treachery and ambiguity. A single thread is as fragile as gossamer, pull it and it snaps; but try to get out of the web and you only tangle yourself up worse. And the mean and weak rule over the strong.

If I have one criticism of this translation, it is that it sometimes follows Hayward and Harrari’s too closely. The frosts in both versions are almost always hoary, and tricky descriptions of color are often interpreted similarly. I’m inclined to cut Pasternak Slater some slack on this. Not only was the Hayward-Harrari version the definitive translation for over 50 years, but Pasternak Slater also studied under Hayward at Oxford University while the latter worked on the translation.

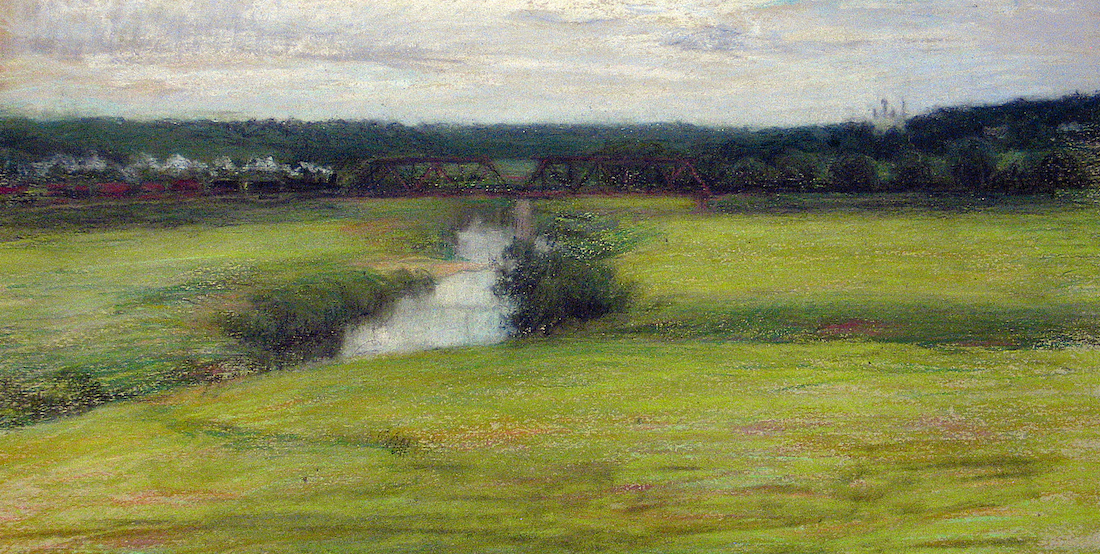

It’s worth saying a few words about this particular edition, which, in many ways, adds to the charm of reading Doctor Zhivago. While the previous translations were achieved in teams of two, this newest version is a family affair. Though Nicolas Pasternak Slater never met his uncle — Pasternak Slater was raised in England and was denied a visa when he attempted to visit the Soviet Union in 1959 — he was among the novel’s first readers: Isaiah Berlin brought Pasternak Slater’s family a smuggled typescript after visiting Pasternak at his home in Peredelkino in 1956. Other Pasternaks were also involved in the new translation. The book is beautifully illustrated with reproductions of watercolors and drawings by artist Leonid Pasternak, Boris’s father, and were carefully selected from the family’s archives by Maya Slater, Nicolas’s wife. Many of Yuri Zhivago’s poems were translated by Lydia Pasternak Slater, Pasternak’s sister (and Pasternak Slater’s mother). Finally, Nicolas’s sister, Ann Pasternak Slater, supplies the edition with its introduction. (Though the book comes furnished with a handy family tree to help readers keep track of the novel’s characters, it fails to offer one for the many Pasternaks involved in its production.) The illustrations make this work particularly special; the similarities between the novel’s descriptions and the found images are uncanny. Underscoring the family’s ties to the novel, many of the illustrations that stand in for characters Yuri, Tonya, and Lara are in fact portraits and sketches of Leonid, his sisters, and mother.

The translation was commissioned and published by The Folio Society, a London publishing firm known for its high-quality editions of literary classics. As a bibliophile, I can appreciate the care they’ve taken with Doctor Zhivago: each cover is half bound in calf leather and wrapped in hand-marbled paper, the paper edges are gilded, and every copy is signed by Pasternak Slater. It’s somewhat eerie to contrast this sumptuous edition with the novel’s origins, first smuggled out of Moscow as a faint typescript in 1956. A covert CIA operation ensured that copies made their way back behind the Iron Curtain by putting a bootlegged imprint into the hands of Soviet tourists at the World’s Fair in Brussels. Many tourists tore the novel into smaller chunks, which were easier to hide in their luggage on their return voyage. Some Soviet émigrés, such as the infamous pirate-printer Alec Flegon, profited from producing cheap, unauthorized paperback versions that were introduced into the Soviet Union and circulated as tamizdat (like samizdat, but made “over there” or tam). When the novel was finally published in Pasternak’s home country in 1988, it was serialized in the prestigious but flimsy literary journal Novyi Mir. The Folio Society edition eschews the novel’s ephemeral, grubby material history; instead, each copy has a silk ribbon place marker and the title is stamped in gilt on the spine.

For now, The Folio Society has only made the novel available in this “special edition,” limiting the print run to 750, and pricing each at $550. But a more affordable edition is currently in the works — and this might, at long last, restore Pasternak’s reputation among English-speakers, making it clear that he well deserved the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1958. In 1956, Pasternak implored Isaiah Berlin to help Doctor Zhivago travel the world and, quoting Pushkin, “lay waste with fire the hearts of men.” Soon, Pasternak Slater’s translation will have a chance to reignite that fire.

¤

All illustrations by Leonid Pasternak used with permission of The Pasternak Trust. This edition of Doctor Zhivago is exclusively available from The Folio Society.

¤

LARB Contributor

Christine Jacobson is assistant curator of Modern Books and Manuscripts at Harvard University’s Houghton Library. She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and tweets at @internetstine.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Undercover Lovers, or How The CIA Became Style

Greg Barnhisel considers how our stories about the Cold War are evolving from politically urgent realist narratives to a narrative convention itself.

The Creative Potentials of Unsuccess: On Karolina Pavlova’s “A Double Life”

Vadim Shneyder disentangles “A Double Life,” an important 19th-century novel by Karolina Pavlova, translated by Barbara Heldt.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!