Girls and Men: On Svetlana Alexievich’s “The Unwomanly Face of War”

Oksana Maksymchuk and Max Rosochinsky consider “The Unwomanly Face of War” by Svetlana Alexievich.

By Max Rosochinsky, Oksana MaksymchukSeptember 8, 2017

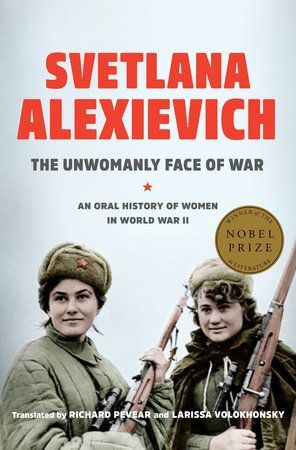

The Unwomanly Face of War by Svetlana Alexievich. Random House. 384 pages.

“THEY BEGIN to talk softly, and in the end almost all of them shout,” writes Svetlana Alexievich in The Unwomanly Face of War, a book of interviews with women who fought with the Soviet Army in World War II. Alexievich conducted most of these interviews in the early 1980s, before the reforms of perestroika. In those years, a joke shared at the wrong moment with the wrong person could land one in a labor camp. Self-censorship became second nature. The young and curious Alexievich, with her brand-new voice recorder, faced a wall of habitual distrust. “Why does she want to know about the past?” her respondents must have wondered.

Initially, Alexievich had to approach women she had heard about from friends and acquaintances. But when her project took off, women started approaching her. The interviews weren’t easy to conduct. These are not conversations that Soviet-born women readily have with strangers. The project required trust, and trust takes time. Alexievich recalls that most of the interviews took “many sessions,” full days of listening and waiting. Interviewer and subject would sit for hours, drinking tea and chatting about everyday things, “recently bought blouses […] hairstyles and recipes.” Eventually, the conversation would take an inward turn. Alexievich describes “this long-awaited moment, when the person departs from the canon — plaster and reinforced concrete, like our monuments — and goes on to herself. Into herself.”

The descent into the self that Alexievich describes is accompanied by a shift in tone, a gradual shattering of the smooth cadences in which older women tell stories to the young. In the English translation, one cannot hear these tonal shifts or differentiate between distinct voices quite as easily as in the Russian original, but the images are preserved. Whole visual sequences are crammed into short phrases, each straining to unfold into a world of its own. Indeed, the reading experience isn’t just visual, it’s cinematic, with scenes shifting rapidly, but the larger themes staying the same: love, death, suffering.

And yet, while The Unwomanly Face of War is cinematic, it isn’t a typical epic war film. It doesn’t force itself on the reader, doesn’t shout. The remembrances of female soldiers are punctuated by Alexievich’s reflections on her project as a writer. What hidden knowledge was she hoping to uncover in her investigation? How would she determine what material was worthy of inclusion and what should be left out? What authority did she, a young journalist, have to make these decisions?

Ironically, it was a Soviet censor who had nudged her toward an answer. During a review of her project, Alexievich explained to the censor that she was after the truth. The censor ridiculed the narrowness of her vision: “You think the truth is what’s there in life. In the street. Under your feet. It’s such a low thing for you. Earthly. No, the truth is what we dream about. It’s how we want to be!”

Alexievich’s focus on military women’s oral history was informed by her wish to resist the truth “we dream about.” This “official truth” was so powerful that it trumped facts. The pressure to conform was strong: after the war, any expression of disappointment or dismay at the ghastly human cost of our Victory could lead to an accusation of treason. Women’s memories, Alexievich found, were less likely to have been contorted to mirror the ideologically sanctioned narratives. These were raw subjective impressions, not yet hardened into oft-told tales: as Alexievich points out, “No one but me had ever questioned my grandmother, my mother.” Like frescoes in sealed-up ancient rooms, women’s memories remained well preserved, vibrant.

While male veterans often sounded like history teachers or state museum guides, women told of their distinctly personal experiences, revealing intimate details. Sometimes what was said — what the women heard themselves saying, often for the first time — was so strange that they worried Alexievich would think they were making things up. In contrast to the glossy truth of “our dreams,” their private stories seemed like fictions. These personal memories lacked all the hallmarks of traditional war stories: “[h]ow certain people heroically killed other people and won. Or lost. What equipment there was and which generals.” The women’s words evoked a different war, a war with “its own colors, its own smells, its own lighting, and its own range of feelings.”

It is important to Alexievich that these women did not think of themselves as war heroes. In their stories “[t]here are no heroes and incredible feats, there are simply people who are busy doing inhumanly human things.” When the respondents remind her that they are “heroines,” it is usually to talk her into making their stories more serious and dignified. In one representative case, the former medical assistant of a tank battalion uses the term to justify her request not to publish the story as it was told. She urges Alexievich to tell it “the way other people tell and they write in the newspapers — about heroes and great deeds, so as to educate the youth with lofty examples.” Thinking of oneself as a hero can be confining in precisely this way. A hero is an example to others. She cannot disappoint, expose her weaknesses. Her honorary title generates a pressure to conform to norms, to tell her story from a position of strength and certainty. Yet a heroic posture is itself vulnerable. A hero must protect herself from revealing too much; she cannot be seen to fall victim to a practical joke, to bare her breasts for a dying soldier, to menstruate. Alexievich enables these women to present themselves as they remember themselves, not as Soviet ideology dreamed them to be.

But if they weren’t heroes, who were they — these women who fought in the “Great Patriotic War”? The translators, Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, use the word “girls” to convey two Russian terms, devochki and devushki. This choice does not violate any dictionary definition, but, as many students of Russian discover when addressing female strangers under 40 years old, the terms have different connotations and are not interchangeable. In Alexievich’s book, the singular devochka usually refers to a female child. In the plural, the diminutive-sounding devochki functions as a term of endearment. Women use it to address their friends in intimate contexts, and men use it to remind women of their tender age. Outside of casual conversation, the frontline women usually refer to themselves and their female peers as devushki, a term that refers specifically to young women in their teens or older.

The use of “girls” in the English text actually foregrounds the gender disparities that Alexievich brings to light. This effect is especially striking in mixed gender contexts in which the women’s peers or subordinates are men:

Within a year I was promoted to the rank of junior sergeant and appointed commander of the second gun, which was serviced by two girls and four men.

The fact that a girl was commander of a platoon of men, and was herself a sapper-miner, became a sensation.

Men looked at us with admiration: “Not laundresses, not telephone operators, but sniper-girls. It’s the first time we’ve seen such girls. What girls!”

These statements, and many more, demonstrate an absurd double standard. War turns boys into men, and men into heroes. But women die as girls.

When the women who fought with the Soviet Army didn’t die, they usually survived in silence. At the beginning of the book, Alexievich wonders why the women had stayed silent for so long, why they hadn’t stood up for “their words and their feelings.” “They did not believe themselves,” she suggests. A former antiaircraft artillery commander gives a fuller account:

We were silent as fish. We never acknowledged to anybody that we had been at the front. We just kept in touch among ourselves, wrote letters. It was later that they began to honor us, thirty years later … to invite us to meetings … But back then we hid, we didn’t even wear our medals. Men wore them, but not women. Men were victors, heroes, wooers, the war was theirs, but we were looked at with quite different eyes.

These “different eyes” emerge time and again through the narratives. In the eyes of the general public, the women who came back from the war were whores, monsters, or worse. When they exposed their military past, they were harassed, shamed, dumped. Men were honored as heroes, and this helped them make sense of what they had gone through during the war; they took pride in wearing their decorations, and were treated with respect and even awe at public gatherings. By contrast, well-meaning parents and friends advised women simply to forget the war altogether.

The heroic daughters of Belorussian war legend Vasily Korzh recalled their father’s way of helping them heal after the war: “He took our medals, decorations, official acknowledgments, put it all away, and said, ‘There was a war, you fought. Now forget it […] Put on some nice shoes. You’re both beautiful girls … You should study, you should get married.’”

Alexievich often speaks of “two wars”: the war women fought when they went to the front, and the war they kept fighting when they came back. Each, she says, was terrible. This book tells the story of that twofold war — and of the cost of survival.

¤

LARB Contributors

Max Rosochinsky is a poet and translator from Simferopol, Crimea. His poems had been nominated for the PEN International New Voices Award in 2015. With Maksymchuk, he won first place in the 2014 Brodsky-Spender competition, and co-edited a NEH-funded anthology Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine (Academic Studies Press, 2017). His academic work focuses on twentieth century Russian poetry, especially Osip Mandelshtam and Marina Tsvetaeva.

Oksana Maksymchuk is the author of two award-winning books of poetry in the Ukrainian language, Xenia (2005) and Catch (2009). Her translations from Ukrainian and Russian have appeared in the Best European Fiction series (Dalkey Archive Press), London Magazine, Words Without Borders, Poetry International, and others. Maksymchuk won first place in the 2004 Richmond Lattimore and in 2014 Joseph Brodsky-Stephen Spender translation competitions. She is a co-editor of Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine, a NEH-funded anthology of poetry (forthcoming). Maksymchuk teaches philosophy at the University of Arkansas.

LARB Staff Recommendations

From the Sun City of Dreams to the City of Angels: A Conversation with Belarusian Artist and Author Artur Klinau

Sasha Razor interviews the Belarusian artist and author Artur Klinau.

Mad Russia Hurt Me into Poetry: An Interview with Maria Stepanova

Cynthia Haven talks to Russian poet, journalist, and political activist Maria Stepanova.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!