Get Lost: On Daniel Asa Rose’s “Truth or Consequences”

Julie Morrison reviews Daniel Asa Rose’s “Truth or Consequences: Improbable Adventures, a Near-Death Experience, and Unexpected Redemption in the New Mexico Desert.”

By Julie MorrisonAugust 23, 2023

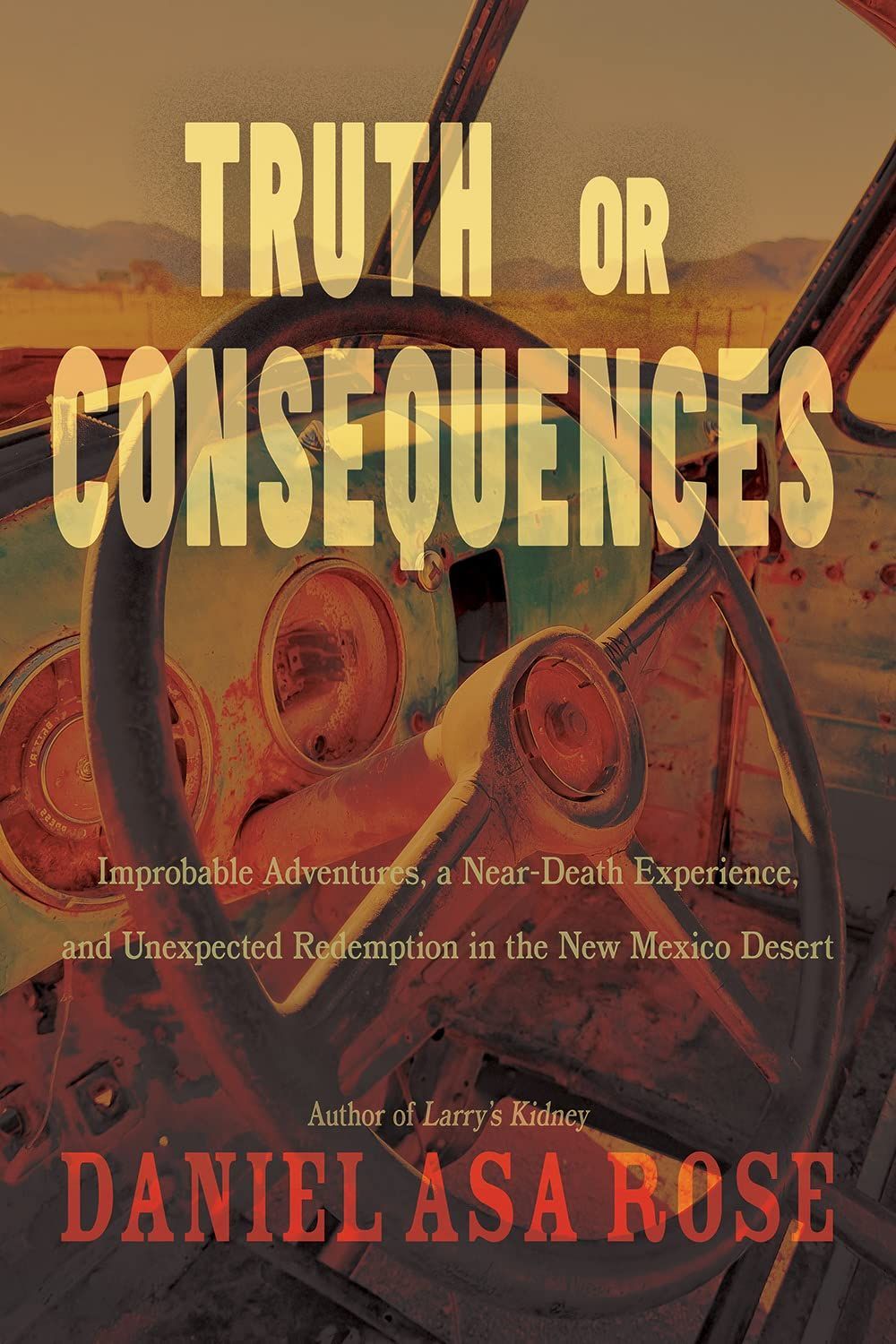

Truth or Consequences: Improbable Adventures, a Near-Death Experience, and Unexpected Redemption in the New Mexico Desert by Daniel Asa Rose. High Road Books. 264 pages.

I REMEMBER eagerly driving south from Albuquerque on Interstate 25 when I was a planner under contract to the New Mexico Department of Transportation. I wanted to see the towns behind the legendary names: Hatch of chile fame; Las Cruces, where Billy the Kid was jailed; and Truth or Consequences, renamed for a 1940s radio game show contest. Sadly, I ran short of time—so no Hatch—and I must have passed through the other towns short on attention because all I remember from that trip was being asked if I wanted “red, green, or Christmas” chiles.

Memory is inclined to favor the novel and the brief. The chile question was both. Daniel Asa Rose’s new memoir, Truth or Consequences: Improbable Adventures, a Near-Death Experience, and Unexpected Redemption in the New Mexico Desert, is a mix of cinematic imagery and cross-country–length prose with plenty of novelty but not much brevity.

As its full title implies, Truth or Consequences tells Rose’s story as he travels from Connecticut to New Mexico on a quest to change his life direction from emotionally absent husband and father—recently served with divorce papers—to “that better person I always hoped I could be.” The trip is not actually his idea: his best friend, Tony, calls from Truth or Consequences (TC) and convinces Dan to join him.

This big-named small town had been the site of a car accident involving Tony and Dan in the summer of 1970. They had graduated college and, both being in their twenties, took a road trip to celebrate. Now they’ve resolved to revisit the crash site, find out why they survived, and locate “the Guardian Angel,” a blonde woman who found and stayed with them until emergency services arrived. Dan senses that she “holds the key to something without which [his] existence will be incomplete.”

Story doctors talk a lot about “intention and obstacle,” meaning that stories need a clear focus on the main character’s strongest desire and the trouble they have on the way to fulfilling it, or not. Unfortunately, Rose’s intentions are both too numerous (visit friend, revisit crash site, find mysterious woman) and too vague (“better” person can mean a lot of things). Once he gets to TC, the story stays there, introducing a stream of outlandish characters without getting back to either “that better person” or “the key to something” that could change him from a character meeting interesting people to, in the words of Joseph Campbell, a hero on a journey.

This is a book for those who love New Mexico, see detour or road closed signs as an opportunity rather than a frustration, and are in the mood for the book equivalent of people-watching from a sidewalk café. No one we meet is boring. At breakfast, Tony slings a “disc of burned yolk across the room into the kitchen sink” as he deems TC “the world’s wildest exaggeration spot” where “[h]ippie culture meets Wild West.” A former junkyard owner throws stones to keeps snakes away as he points out shrines to those killed along a segment of highway he calls the “death stretch […] ninety miles of hell.” It’s the same stretch that could have claimed the author. Head Shop Harry traces TC’s history from its beginning as Hot Springs through its stint as a debauchery destination for resort workers from the less-permissive Elephant Butte to its renaming for a game show. The town itself is an actor in this story that will “break your heart or heal your soul, sometimes neither and sometimes both at the same time. The story of America, writ small but writ spicy.”

Colorful as they are, though, the characters are also hard to differentiate. For example, when Dan meets the local AA group (the first A standing for an unprintable plural noun), where “[e]veryone is brilliant in their own way,” it’s difficult to identify who’s who within the everyone. Aside from a few grammatical markers like “hisself” and “ain’t,” any of Bird Brain, Roy Joy, Clay, Colonel, Hap Hazard, and others could be Tony speaking—or the author himself. For example, in Moon Dog’s introductory speech we read, “I’d appreciate if you’d use my real name, everyone. I’ve earned it, ain’t I, with eighteen years’ sobriety? My sobriety’s old enough to vote, for cripes’ sake! Anyway, it’s nice to not be on a wanted poster anymore, though it is kinda lonesome not being wanted.” Too similarly in tone and syntax, Bird Brain tells us, “As most of you blowhards know, I chose to live in T or C just because there’s only one stoplight. Can’t say why the notion of one stoplight appealed to me: it just did. Anyway, I’m here to tell you that shit sneaks up on you, that it do.”

Fact, reflection, joke. The pattern repeats again and again with character introductions and dialogue. While the jokes land, this book’s style is far more Dave Barry Slept Here than Travels with Charley.

Some books need to be books because of their literary writing, while other books have plots or character sketches that better lend themselves to movies. Truth or Consequences has characters with personalities big enough to fill any screen. Some readers will enjoy their clichéd presentations—“The words stick in my throat,” “Wow, they really did buy it hook, line, and sinker”—punctuated by sounds—“Rev, rev!” and “ZAAAAAR yah-yah-yah-yah-yah” for motorcycles or “Boop-boop-de-doop-oop!” to describe “a tune from long ago.” These elements distracted me, as did studied word choices. When Dan confronts a biker gang, for example, the scene reads: “Out the car I go, sauntering toward the bikers like I’m on a school picnic. The glare they train on me is pure truculence, designed to stop an eighteen-wheeler from even dreaming of entering their lane. With a belligerent thrust of his wrist, one of the bikers cranks his engine even louder.” Sauntering, truculence, and belligerent are writer words: descriptive selections made by a narrator a safe distance away from gas station, asphalt, and hostile faces. Their effect, however, also distanced me.

Thankfully, by the end of the book, Dan doesn’t need us to stay close. He’s found and helped the family of the Guardian Angel, become a cautious driver in no danger of being claimed by highways of any length or reputation, and is being “the best ex-husband [he] can be.” I didn’t relate to his journey, but let’s note that I am female, some years behind the nostalgia for wanderlust road trips in the 1970s, and easily annoyed by bumper sticker self-help mantras. What was charming to Dan in his turning-point moments turned me off, but that’s what preferences do, like choosing between red or green chiles: we can acknowledge complexity and effort but can’t make ourselves really like what isn’t for us.

Read this book if you want to spend some time in a quirky town with so many oddball characters and one-liners that you’ll probably lose track of both. Don’t worry. As Dan has described, this is a friendly place to get a little lost.

¤

Julie Morrison is a memoirist, short-story writer, and poet from Arizona. Learn more at her website: juliemorrisonwriter.com.

LARB Contributor

Julie Morrison is an Arizonan, memoirist, short story writer, and MFA candidate focused on poetry at Seattle Pacific University (August 2023). Her prose has been published in Barbed: A Memoir, Los Angeles Review of Books, two Desert Sleuths mystery anthologies, Ladykillers and Love Kills, and is forthcoming in the summer 2023 edition of The New Guard. Her poetry has been published by the 2020 Arizona Authors Association Literary Awards and the 2023 San Diego Poetry Annual.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Adventures in the Sky and Misadventures on the Ground: On William D. Kalt III’s “America’s 1890s Parachute Queen” and Jana Bommersbach and Bob Boze Bell’s “Hellraisers and Trailblazers”

Julie Morrison reviews two books about 19th-century Wild West women.

Two Questions for Rudolfo Anaya

An homage to the Father of Chicano literature, Rudolfo Anaya

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!