Adventures in the Sky and Misadventures on the Ground: On William D. Kalt III’s “America’s 1890s Parachute Queen” and Jana Bommersbach and Bob Boze Bell’s “Hellraisers and Trailblazers”

Julie Morrison reviews two books about 19th-century Wild West women.

By Julie MorrisonFebruary 27, 2023

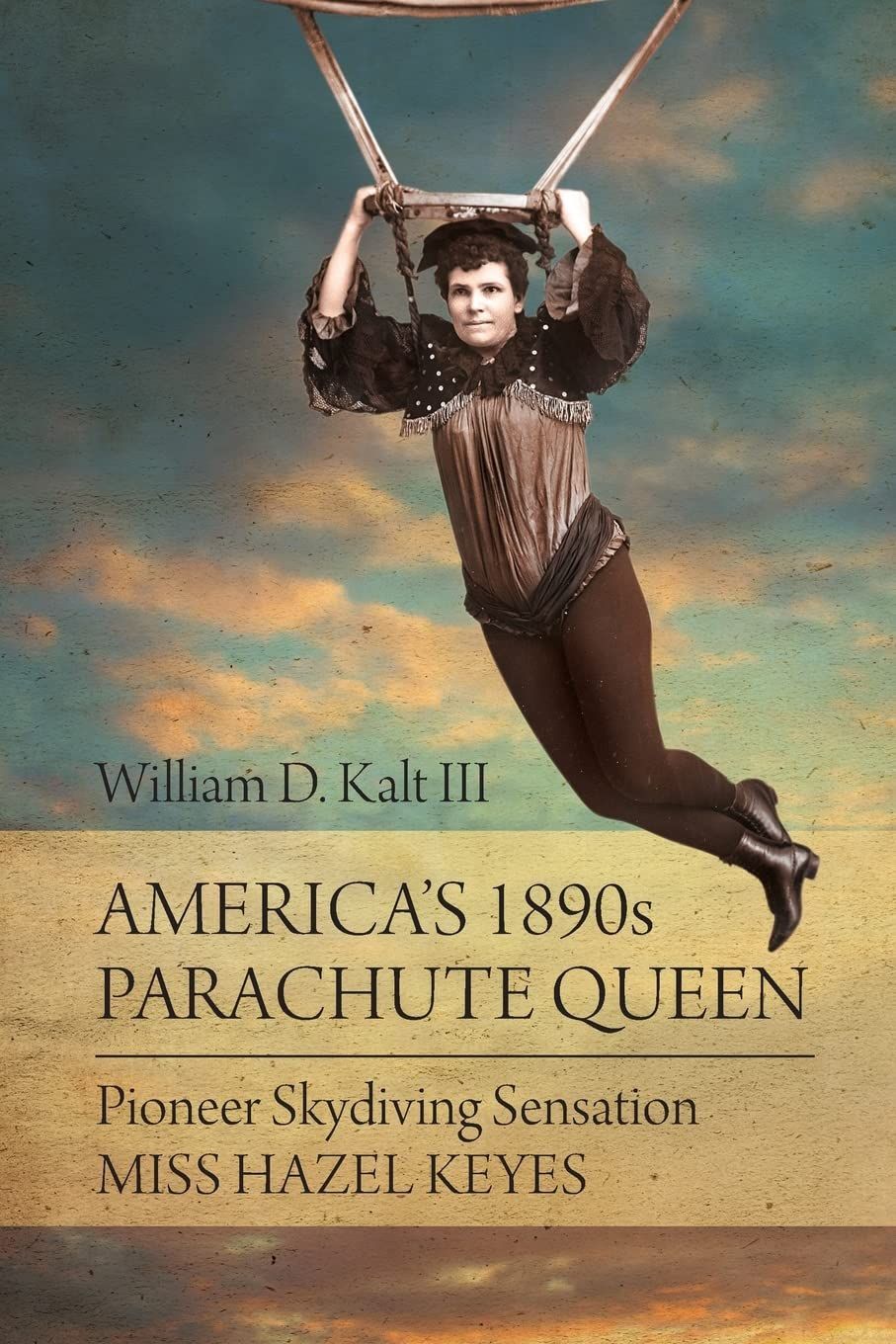

America’s 1890s Parachute Queen: Pioneer Skydiving Sensation Miss Hazel Keyes by William D. Kalt III. Universal Publishers. 182 pages.

Hellraisers and Trailblazers: The Real Women of the Wild West by Bob Boze Bell and Jana Bommersbach. Two Roads West. 126 pages.

“WELL-BEHAVED women seldom make history,” reads the bumper sticker. The saying comes from an obscure academic paper, “Vertuous Women Found: New England Ministerial Literature: 1638–1735,” published in American Quarterly in 1976 by Harvard professor Laurel Thatcher Ulrich. It’s tempting to let a line like this stand on its own, unattributed, especially when it’s used as a teaser for material to come. Stories are better uninterrupted. Histories are better sourced. True stories happen somewhere between the two, borrowing elements from both.

That Jana Bommersbach and Bob Boze Bell use the line about well-behaved women as an unattributed quote in their introduction indicates the type of storytelling about to happen in Hellraisers and Trailblazers: The Real Women of the Wild West. This is a rundown of famous and infamous women who settled and unsettled the West via navigation, politics, homesteading, publishing, lecturing, exhibition riding, ranch work, and, yes, prostitution and murder.

Its recent release complements a single-subject biography of a remarkable miscreant, America’s 1890s Parachute Queen: Pioneer Skydiving Sensation Miss Hazel Keyes, by William D. Kalt III. Keyes parachuted from hot air balloons, solo and in tandem with partners including men, monkeys, dogs, and chickens. She completed hundreds of jumps between 1890 and 1900, for crowds of spectators that sometimes numbered in the thousands. Though not the first woman parachutist, she managed “50 years of news-making events” for her adventures in the sky and misadventures on the ground.

The spirit of these books is similar: enthusiastic descriptions of women whose contributions have been effaced. But the delivery is wildly different, with fact and opinion woven seamlessly into unsourced narrative in the former book and a parade of footnoted prose marching along the subject’s timeline in the latter.

Hellraisers and Trailblazers highlights women from Sacagawea to Sharlot Hall who shaped some part of “the West.” Readers meet Martha Summerhayes playing tennis at Fort Apache, in present-day Arizona, alongside Sarah Winnemucca on a mission to “correct the sins of the reservation system.” The presentation of one woman after another is as fondly pell-mell as a reel of a high school graduate’s childhood milestones: stories wrapped around portraits, photos, maps, newspaper clippings, playbills, and photos. There is no table of contents, just a full-color dive into the authors’ accumulation of research and reporting, with credit given to historians, researchers, and writers on the last page of the book, but with very few references included in the text.

Bommersbach and Bell have published the equivalent of a film documentary with many engaging pictures, not often stopping to say where they’re from. The writing is approachable to the point of colloquial, giving equal weight to fact and argument, as in the description of stagecoach robber Pearl Hart: “They were captured, and the press at the time […] went nuts, making her a celebrity whose notoriety spread across the nation. Her trial and incarceration — the first jury acquitted her even though she’d confessed — are gems of Western History.”

The prose is like a tour guide’s script for a women’s history museum, and it would likely entertain its visitors to the point of tipping the guide. But in a book, I would prefer a less superlative and more substantiated take on history, trading admiration for annotation.

America’s 1890s Parachute Queen, by contrast, serves a generous helping of references alongside the spicy and, at times, disgusting hash Keyes made of her life. Though she contended successfully against winds, explosions, fiery accidents, and hard landings, the parachutist’s personal ups and downs were far more damaging.

Kalt does an admirable job of tracking Keyes through her many names and addresses, but we don’t know much about the why behind the facts of her life — for example, why a person elects to jump from thousands of feet in the air at all, let alone hundreds of times. From the August 25, 1893, edition of the Washington Standard, we learn why Keyes found parachuting from balloons to be “simply delightful”:

[T]he view is grand beyond the power of words to describe. You seem to float in a sea of ether, and your spirits are as light as those of the bird which goes twitting by, your only companion. The view is much different from that obtained, or the sensation experienced, on the mountain top. […]

The verdure of the trees beneath me, today, appeared as a great carpeting of moss. The bay seemed like a sheet of silver, bordered by deeper hues and the reflection of the distant mountains.

Perhaps she was fearless. Perhaps the freedom was incomparable. But Kalt does not indulge in conjecture, limiting himself to the glimpses of motive available within newspaper interviews.

Kalt does allow himself flowery speech similar to his subject’s, writing with feelings as exuberant as a circus barker. Introducing the Los Angeles chapter of Keyes’s life, he says: “The degree to which her aerial game’s injuries, trials, and challenges exacted their respective mental, physical, and emotional fees and helped sculpt this feisty, tough, steel-willed, attractive, courageous woman comes into question.” The dated syntax is not an isolated event within the book. To conclude the chapter about the parachutist’s bad falls, Kalt writes that “one might speculate regarding the enduring toll of pain, such collisions with the earth exact, and their cumulative debt. Biological and anatomical science suggest that their sum might create a usurious tax upon one corporeal vessel.” The antique language may be endearing to fans of linguistic history, but it may also be difficult or obscure for readers accustomed to modern narration.

Keyes’s land-based behavior was notable mostly for scandals. As brave as she was in the air, Keyes was also an unfaithful wife, an enabler of her murderous pedophile son, a spendthrift, and an abuser of animals. Parachuting with a monkey who survived each jump uninjured is a matter of husbandry standards that I don’t share, but feeding hogs only trash from the city dump laced with broken glass and “chloride of lime” is inhumane.

I am sympathetic to the many hardships of Keyes’s life: navigating a “subsistence” childhood, bearing her first child at 15, marrying two years later, and enduring three bad marriages overall. But I am also sickened at the trouble she authored herself. She secured an early parole for her imprisoned son, Eddie, which he promptly used to kidnap and molest a seven-year-old boy. Posting bond after his arrest, she eventually set him up in a new business with access to money and a checkbook, freedom he used to kidnap, abuse, and kill another child. Kalt doesn’t shy away from this side of Keyes.

Both books chronicle women who rejected contemporary norms as wives, mothers, domestic workers, or teachers. But historians face difficult questions about presentation. How can they best frame events to avoid a drab recounting of fact? Bommersbach and Bell tell stories to intrigue and entice, giving readers curated pieces of women’s history in an enthusiastic mosaic. Kalt spares no effort to report the detailed events of a female parachutist’s life but cannot make her truly sympathetic. Behavior, and history, is made not by chance but by choice — originally by the historical figure, then by reporting writers. Readers may decide whether or not it’s made well.

¤

Julie Morrison is the award-winning author of Barbed: A Memoir. Learn more at her website.

LARB Contributor

Julie Morrison is an Arizonan, memoirist, short story writer, and MFA candidate focused on poetry at Seattle Pacific University (August 2023). Her prose has been published in Barbed: A Memoir, Los Angeles Review of Books, two Desert Sleuths mystery anthologies, Ladykillers and Love Kills, and is forthcoming in the summer 2023 edition of The New Guard. Her poetry has been published by the 2020 Arizona Authors Association Literary Awards and the 2023 San Diego Poetry Annual.

LARB Staff Recommendations

These Creatures: On Cosey Fanni Tutti’s “Re-Sisters”

Arielle Gordon reviews Cosey Fanni Tutti’s “Re-Sisters: The Lives and Recordings of Delia Derbyshire, Margery Kempe & Cosey Fanni Tutti.”

Frank Bergon: New Old West Mystifier

A Western writer blends elements of cowboy myth with modern brawling.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!