Football Nation: The NFL Brand in the Year of Kaepernick

On how the NFL achieved "corporate transcendence" and what the era of Kapernick means for it.

By Aaron DeRosaFebruary 4, 2017

EVERY YEAR, the most watched public event in the United States is a four-hour commercial for the National Football League. A spectacle anticipated not only for its athletic competition but also for its advertising, the Super Bowl draws together the nation in unheralded ways. For most viewers, the teams don’t matter. For some, the main draw are the commercials. But even at $5 million for a 30-second ad, these spots don’t hold a candle to the greatest advertising coup each year: the real and emotional investment in the NFL itself. In a season marked by deep divisions wrought by the national elections, this is a signature year for the NFL brand.

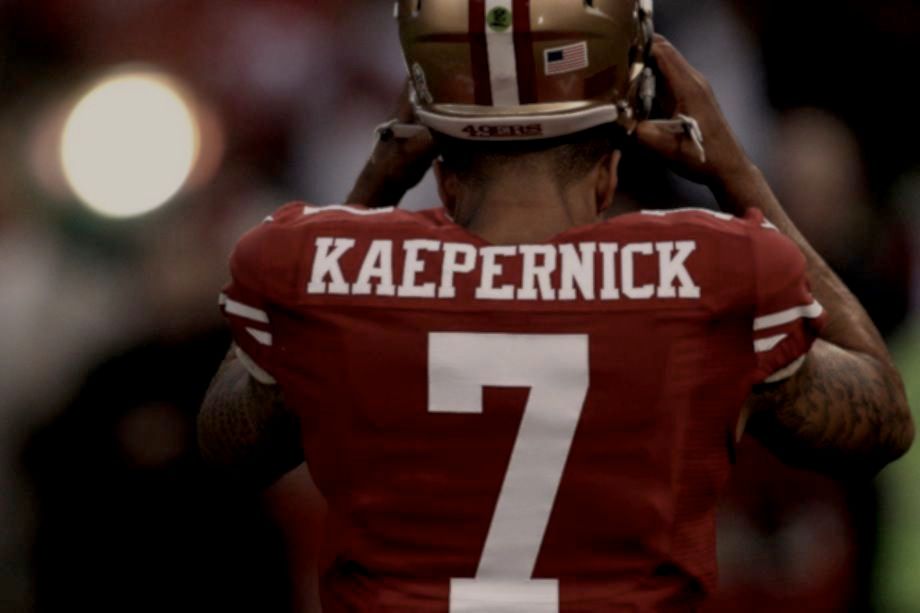

With only 11 minutes of active play out of a 185-minute broadcast, the game’s drama always builds beyond the hashmarks. The Super Bowl is the culmination of a year’s worth of football narratives: last-second field goals and devastating injuries, rivalries and breakouts, a narrative of winnowing paths and minor spectacles. Brands thrive on stability, and the 2016–2017 NFL season promised to open without incident. Having put Beyoncé’s public display of blackness (PDB) in the 2016 Super Bowl halftime performance behind it, the league was poised to begin the season with a clean slate. The offseason was free from domestic and sexual violence headlines (Ben Roethlisberger in 2010, Ray Rice in 2014), cheating accusations (the Patriots in 2015), and labor disputes (players in 2011, referees in 2012). It was also clear of medical scandals (the concussion settlement of 2013) and no notable suicides (Junior Seau), homicides (Aaron Hernandez), or targeted violence (Bountygate). The NFL was headed for a quiet start; that is until a cameraperson captured Colin Kaepernick, a quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers, taking a knee during the national anthem in his final preseason game in protest of police violence against people of color.

Scandalous and riveting, the racialized narrative of the “Kaepernick Effect” — and its coded alternative, “the 2016 ratings decline” — will reach its terminus in the Super Bowl. Typically, the Big Game is the space where all scandals are purged and the stability of the brand is confirmed. But Kaepernick’s protest rewrote Beyoncé’s Super Bowl halftime show from season 50 climax to season 51 cliffhanger. Kaepernick would soon be joined by players and teams across the league, as sportscasters and pundits loudly denounced them. A #boycottNFL movement arose. Football ratings dropped. Business writers and journalists piled on: the NFL had alienated its largely white fanbase. Would the “Teflon brand” that had withstood so many other scandals lose to white nationalism? The NFL’s bottom line seemed to suffer. Could it recover?

The stakes are high, high enough to be the foundation for a long-running drama and the basis for a spectacular season finale. Whatever narrative unfolds at the 51st Super Bowl, whatever the outcomes, one way or another the Kaepernick effect will be metabolized by the forces driving the NFL’s scandalous brand.

The NFL Brand

Brands are complex organisms, having evolved from simple beginnings — consistency in name, logo, and packaging in the late 19th century — to endless forms most beautiful. Today, the most highly evolved brands like the NFL, Nike, and Apple promote “lifestyles” — attitudes, behaviors, and communities — associated with their products. The goal of the lifestyle brand isn’t to promote the sale of a given product with a simple TV ad and a catchy jingle; the goal is to associate a set of behaviors and ideas with a company. When successful, brands achieve what Naomi Klein describes as a form of “corporate transcendence,” a value that exists not in the corporation’s material assets but in the minds of consumers “as experience, as lifestyle.”

The NFL is one of the most wildly successful lifestyle brands. It consistently ranks as Americans’ favorite sport (39 percent compared to 14 percent for the second-place MLB) and Sunday Night Football (SNF) nets the highest ratings of any television show on a weekly basis. But the brand is more than any quantifiable asset: it is a consciously sculpted public image. Take the first Super Bowl. While the league dates to the early 20th century and its modern form arose in the 1970 merger with the AFL, naming the title game the “Super Bowl” was one of the NFL’s first acts of brand identification. For the first few years of merger play, the name of the championship game itself was undecided until the NFL settled on the “Super Bowl” to promote a unified image of American football, and then retroactively applied to the first two championship games. That sense of a league brand would become fully realized in 1994 when, Michael Oriard notes, the NFL hired Sara Levinson, a former head at MTV, as the president of the NFL’s marketing division. The hire underscored the NFL’s decision to target casual fans, women, and children as they sought to manage the league not as a game for the diehard fan but as a lifestyle brand for the nation.

This is recognized today in the Encyclopedia of Global Brands, which identifies the NFL as the “premier sports and entertainment brand.” This generalization — from sports to entertainment company — recognizes the proliferation of promotional sites beyond the field. The points of contact between the NFL and its fans occurs in each individual player’s endorsement and Twitter feed, in jersey sales and the “Play 60” campaign, in the importation of football rhetoric to the workplace and the way people reorganize their idea of “Sunday” during the season. As brand analyst Rob Wolfe put it, “The NFL is not in the football business […] The NFL is a media company that captures the mystique — the football aura — that pulses into the soul of the football fan. And those who aren’t fans of the game are still touched in some way by the NFL brand.” The NFL is a way of life, whether you choose to watch or not.

Twenty-first-century brands combine the power of quantification with the penetration of rationalization into the deepest reaches of personal identity. Twenty-first-century brands, in other words, want to sell you back to yourself at every turn. The ascendance of social science statistics, George Gallup’s sampling methodologies, and advertising research has given Americans a way of seeing themselves as individual collections of data points. When Madison Avenue altered its model from mass marketing to niche marketing in the 1960s and 1970s, it worked in tandem with new post-Fordist production practices. Flexible specialization allowed factories to create diverse product lines for fracturing consumer groups. In football, this meant expanding from a single product line of team logo glassware sold at gas stations in 1959 to customizable jerseys delivered overnight. At the 2016 LA Food & Wine Festival, the NFL sponsored a “Slider Zone” where fans selected their team, crafted a burger, and photo-logued the end product on a team-logo woodcut board.

Consumer participation is the backbone of any successful lifestyle brand, which harnesses what Maurizio Lazzarato described as the consumer’s immaterial labor, a type of labor that produces the “informational and cultural content of the commodity.” That is, a brand may be regulated by brand managers, but allegiant behaviors beyond the site of consumption generates the equity. Lazzarato defines this as a kind of cultural work that takes place outside traditional labor while producing surplus value for the parent company. In the case of the NFL brand, the labor is performed not by the athletes (theirs is a different kind of embodied labor), and even less so Commissioner Goodell and chief marketing officer Dawn Hudson; it is performed by consumers.

Think of how much work fans perform in fantasy football leagues, one of the most popular extensions of the NFL brand. The fantasy football “armchair quarterback” constructs a league, establishes the rules, manages teams and player contracts, and in doing so creates uniquely monetized communities — from the new daily fantasy sports gambling sites to the entry fees and payouts of more traditional leagues. Fifty-seven million participants spent $4 billion dollars on fantasy games in 2014 alone, proselytizing the NFL brand with every draft room entered, every episode of FX’s The League viewed, and every ESPN ranking downloaded.

This is good for the NFL, considering it doesn’t directly make a lot of money from fantasy sports. The most popular hosting sites tend to be Yahoo, ESPN, and CBS Sports, and not the NFL’s in-house option. But the effectiveness of fantasy football in promoting the brand can not be overstated. A growing body of data makes clear that fantasy sports reduces fan intensity for individual teams, but shifts loyalty to the league. And while it decentralizes the league symbolically and economically, it transmutes passive viewers into active participants that promote the NFL across multiple access points and affirms the brand’s transcendence.

Brand Nationalism and Nationalist Brands

Insofar as lifestyle brands operate as communities of shared practices and beliefs, they parallel what Benedict Anderson describes as the imagined community of the nation. For Anderson, nations are imagined in that its members will never know one another but nonetheless remain united in their collective affinities. This social bond is facilitated by newspapers — daily best sellers — that promote a national simultaneity: the sense that all members of the community are experiencing the same event at the same time. While neoliberalism erodes national identity in favor of branded niche communities, today, pro sports are the last great bastion of national simultaneity. As news sources proliferate and more and more homes switch to streaming platforms, sports remain one of the only remaining live events that keeps the nation’s attention. Indeed, this is precisely why the NFL can charge so much for advertising: the limited game nights and compact schedule stabilizes viewership like no other.

The NFL thus functions differently from other lifestyle brands like Apple or Nike in that its chief product is a live simulcast. As more and more brands present themselves as alternatives to the nation in the neoliberal era — from Steeler Nation and Raider Nation to Colbert Nation and Pantsuit Nation — the NFL’s success hinges on its affirmation of nationalist pride. The “Paid Patriotism” scandal — in which the Department of Defense and the National Guard paid the NFL to promote on-field patriotic displays — hardly registered for fans. While the NFL reimbursed American taxpayers, the revelations primarily wound up confirming the already close ties between “America’s sport” and America itself.

Ben Fountain’s National Book Award–winning novel, Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk (recently adapted to film by Ang Lee), painted perhaps the most vivid portrait of military heroism packaged as the “sanctioned savagery” of a football game. The culminating stop on an Army-sponsored “Victory Tour” featuring Billy Lynn and Bravo Squad — the heroes of a fictional battle in Iraq — is a Dallas Cowboys Thanksgiving halftime show (headlined, aptly, by Beyoncé’s Destiny’s Child). Throughout the novel, Lynn is discomfited by the uneasy equivalence drawn between the military and the gridiron, leading him to the epiphany that the United States should send the Cowboys

[T]o fight the war! Send them just as they are this moment, well rested, suited up, psyched for brutal combat, send the entire NFL! […] Resistance is futile, oh Arab foes. Surrender now and save yourself a world of hurt, for our mighty football players cannot be stopped, they are so huge, so strong, so fearsomely ripped that mere bombs and bullets bounce off their bones of steel. Submit, lest our awesome NFL show you straight to the flaming gates of hell!

For Lynn, the Cowboys — and by extension the league — capitalize on the very same myths of masculinity and nationalism as the American military.

Hyping Bravo Squad throughout the novel is an agent trying to sell the motion picture rights to their story. But the truth is that the Cowboys halftime show is the motion picture. The same transitive property that allows Lynn to deploy the Cowboys to Iraq also allows the NFL to render Bravo Squad’s heroics on the gridiron, in all of its telecasted glory. The NFL’s glitz and glamour, its careful editing, its commentators’ skillful narration — it’s not just a good game, it’s good TV. When Jody Rosen praised SNF, he compared it to popular dramas like The Sopranos and The Wire, describing it as “a drama unfolding in real time, captured by dozens of cameras, cut-and-pasted on the fly into a tension-packed narrative, bolstered with graphics and telestrated X’s and O’s and bombastic interstitial music.”

Beyond any individual game, though, the league itself functions like a serial drama. Rosen concludes:

But consider the National Football League. Vampiric corporate overlords, labor exploitation, dubious racial politics, sexism, drugs, gambling, a chronic traumatic encephalopathy crisis, a cover-up of a chronic traumatic encephalopathy crisis — a veritable moral cesspool bubbles and boils beneath the green, green fields of Sunday. And let’s not forget the likes of Roger Goodell and Bill Belichick, antiheroes whose malevolence would send a shiver up the spines of Tony Soprano and Walter White. Talk about Peak TV.

The league’s scandalous pageantry is its gris-gris. The games are a real-time drama, punctuated by acts of controlled violence more spectacular than anything on reality television. It may be simple coincidence that at the height of the sport’s popularity, scandals have proliferated wildly. But the greatest hits of the past decade include a dog fighting ring, domestic violence, a shooting, sexual assault, cheating, on-field bounty hunting, murder, doping, bullying, a different kind of cheating, medical cover-ups, child abuse, and another kind of shooting. It is appropriate that the “greatest show on turf” — the nickname for the high-powered Rams offense from 1999–2001 — calls back to the grandfather of modern advertising, the huckster P. T. Barnum.

The Kaepernick Effect

So the thematic arc of season 51 is the “Kaepernick Effect,” and in more coded form, the decline of the NFL’s ratings. Kaepernick’s act elicited a national backlash toward what some fans and commentators called an ungrateful, anti-veteran, anti-American, narcissistic, cry-baby, half-white race-traitor millionaire. Rodney Harrison, a SNF commentator, suggested Kaepernick wasn’t black and didn’t have the requisite experience to posit an opinion on racial injustice. Trent Dilfer similarly remarked that, as a backup quarterback, Kaepernick’s job was to be a shadow. This was echoed by conservative pundits like Bill O’Reilly and vlogger Tomi Lahren who felt the protest drew attention to the man, not the issue (ignoring the fact that such attention is a function of media coverage, not the method of protest). But that critique got muddled when Kaepernick was joined by players from across the league, across levels (little league and college), and across sports (soccer, basketball). Kaepernick became less a man and more of an “effect.”

When the NFL refused to officially prohibit such political statements, opponents sought to silence protestors by appealing to the league’s sense of brand security. The conversation shifted to the ratings decline. As one writer for Breitbart put it, “if the news on the ratings are any indication, Americans are beginning to get fed up with the constant drumbeat of liberal politics shoehorned into their once beloved forms of apolitical entertainment,” and the NFL would need to make a change. Indeed, the economic sanctions had already begun when Broncos linebacker Brandon Marshall lost two endorsements after protesting. And as the league’s ratings continued to fall, it seemed like a boycott from the most reactionary of fans was working. Business writers, sports writers, and conservative pundits latched onto a Rasmussen poll four weeks into the season that found “Nearly one-third (32 percent) of adults say they're less likely to watch NFL game telecasts because of the Kaepernick-led player protests against racial injustice.” The message was clear: if the NFL wanted to preserve its 77 percent white fan base, it would take a hard line against such racialized protests.

The polls, not for the last time in 2016, proved misleading. Even at its worst, ratings only declined 14 percent: either respondents overestimated their concerns or the league demographic shifted. To the latter, that same poll showed 13 percent of fans were actually more likely to watch after Kaepernick’s protest. But Nielsen ratings actually show that black viewership was in greater decline than white viewership (14 percent and 12 percent respectively), contradicting the narrative that white viewers were the ones most offended by the protests. If history is any indication, though, the most likely answer is that the polls weren’t terribly scientific and respondents may have overestimated their anxiety. During the Ray Rice scandal of 2014, 15 percent of fans reported the incident would impact their viewing, but that never manifested in the ratings (-2 percent overall, +2 percent with women).

Further, the argument didn’t resonate with the league or its sponsors. Regular season advertising spots were still up eight percent from last year and Super Bowl spots are 10 percent higher, with no drop off in sponsors. The millions of dollars of “make goods” — an industry term for paybacks the league provides to sponsors when estimated and actual viewers differ — seen by some as evidence of an increased financial pressure against the league, is a number bound to viewership and not responsive to Madison Avenue anxiety. Instead Goodell consistently rejected the Kaepernick narrative, insisting the ratings drop was attributable primarily to the spectacle of the 2016 presidential election. That narrative seems to have held up, with ratings returning to normal since the election and, as Stephen Battaglio of the LA Times notes, “There is historical precedent for presidential politics pulling viewers away from the NFL” going back to “at least 1996.”

The protests are certainly a factor in this odd season for the NFL brand, but not in the way it has been presented thus far. Far from destroying the brand, the protests are the kind of story the league thrives on; the kind of story the league needs to resolve in order to make the Super Bowl the show audiences desire. Indeed, a report came out last week that the NFL was barring Lady Gaga — a noted Trump opponent — from making her halftime performance political. The NFL called the report “nonsense from people trying to stir up controversy where there is none,” but the attention such controversy draws is precisely what keeps viewers glued to the halftime show searching for the political statements.

For the most part, the NFL succeeds because it holds itself above the scrum. When it comes to scandals involving individual players — if this were just a Kaepernick thing — the league doesn’t suffer. It is up to individual players and teams to resuscitate their own images. The NFL can take this stance because both players and teams are interchangeable cogs in the machine. Players are abstracted X’s and O’s, replaceable after three years (the length of the average NFL career). Not even the quarterback is immune. When future Hall-of-Famer Tom Brady is out, the Patriots are still 13-5. Teams fare no better. From 1982–2002, the league averaged a team relocation once every three years and added four expansion teams. This season, the Rams moved back to Los Angeles with the Chargers joining them in 2017, as well as plans to expand in London and Mexico City. No team is too big to harm the league.

But when the NFL brand is at stake, the league must act. After Goodell bungled the punishment for Ray Rice and domestic violence became a central story line for the 2014 season, Hudson ran an ad from the anti-domestic violence group “No More” in a prime Super Bowl spot. Similarly, at the height of the concussion scandal, the NFL ran a 60-second commercial during the 2012 Super Bowl depicting the evolution of equipment and rules to protect players from injury, with Ray Lewis intoning: “Here’s to making the next century safer and more exciting.” Paired with other initiatives like the annual “Head Health Challenge” to promote innovation in detecting and preventing brain trauma (for both athletes and soldiers), the NFL takes its brand seriously.

What remains to be seen is how the NFL packages the Kaepernick Effect in Super Bowl LI. The protest captured national attention and has become a league-level issue, with players from seven of 32 teams still protesting in week 17, down from a high of 16 in week 3. The Seahawks continued to link arms in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement throughout the season and through two playoff rounds. And despite his subpar play this season, Kaepernick’s jersey ranked 24th in overall sales for the year and he was honored by his teammates with an end-of-season award for courage. It has become increasingly difficult for the NFL to maintain its brand identity as an apolitical extension of the nation when the nation no longer imagines itself outside the political. When the political collapses into the social, the cultural, and the economic, how then does the NFL cultivate its brand?

The NFL could weigh in simply by broadening the scope of “America’s Game.” The league vets all its ads, and may curate a particularly multicultural display of Americana in its sponsors (in the vein of Coca-Cola’s 2014 “America the Beautiful” ad). It could expand its nationalist fervor to include other kinds of national, non-military service. It could finally change Washington’s team name. It might also directly reform its own institutionalized racism by prioritizing the hiring of black coaches, diversifying its owner pool, relaxing rules against end zone celebrations, or expanding efforts to protect players’ physical well-being. The football stadium may be second only to the prison-industrial complex in regulating and destroying the black body.

Whatever steps the NFL does or doesn’t take to relieve the pressure building within it, the Super Bowl is the site in which all of these narratives coalesce. It is an artful exercise of brand management, conducted in real-time, experienced, built, and felt by millions. It’s unlikely that Super Bowl LI will intentionally address American racial tensions. It’s also unlikely to be able to ignore them.

¤

LARB Contributor

Aaron DeRosa is an assistant professor of 20th- and 21st-century American literature at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. His work has appeared in Arizona Quarterly, Studies in the Novel, LIT: Literature, Interpretation, Theory, and MFS: Modern Fiction Studies. He is currently working on a manuscript titled Advertising and American Fiction since 1945.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Sunday Night Football

Football’s Cancer

Exploitative Labor in America's Favorite Sport

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!