Fetid Carpets and Toast: On “Lanny: A Novel”

Magdalena Miecznicka goes in search of “Lanny: A Novel” by Max Porter.

By Magdalena MiecznickaMay 14, 2019

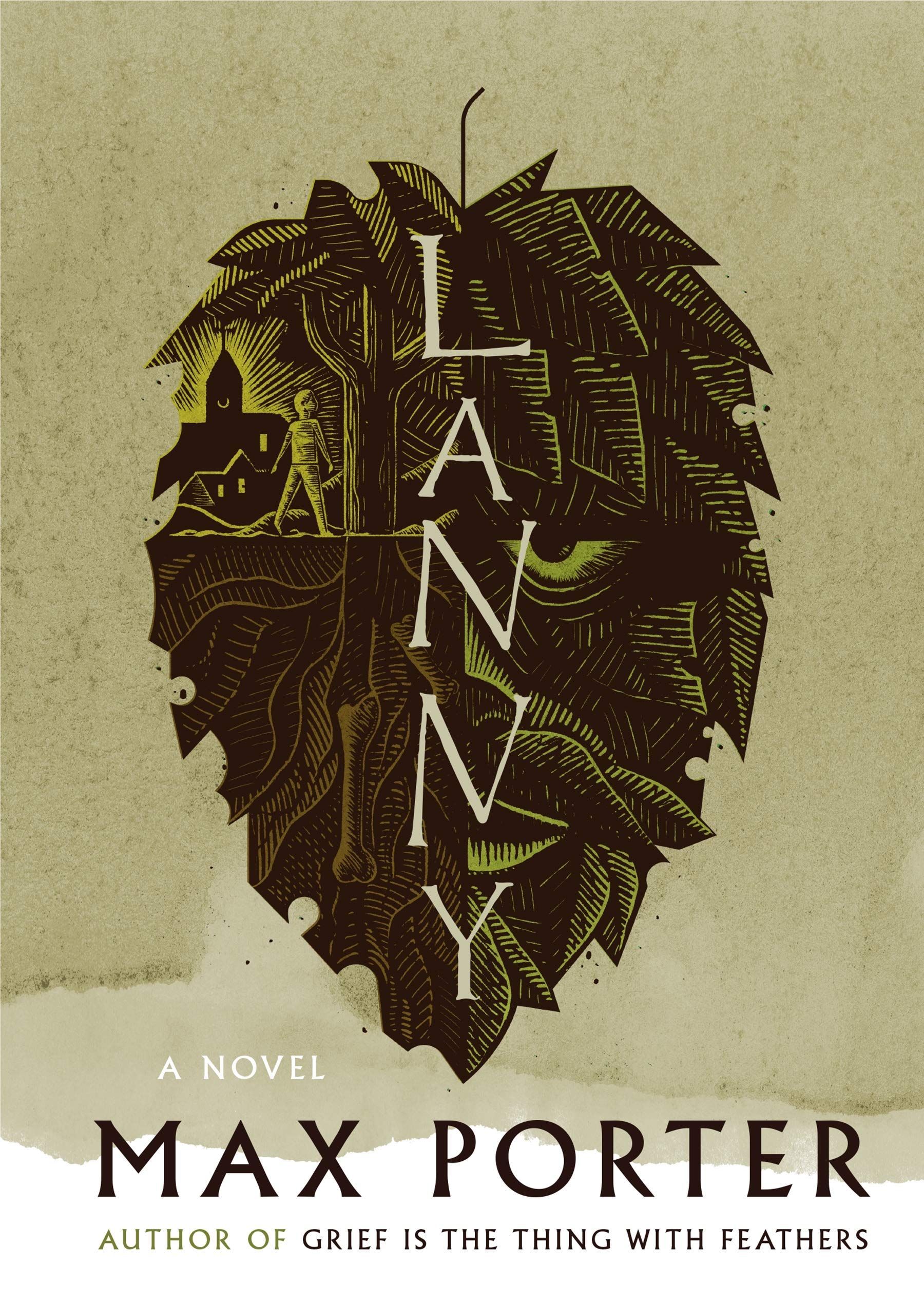

Lanny by Max Porter. Graywolf Press. 160 pages.

MAX PORTER’S SECOND novel, Lanny, comes out four years after his widely acclaimed Grief Is the Thing with Feathers. Porter once again puts a family drama center stage, but now he uses it as a lens to scrutinize not so much the human soul as a broader social scene.

Grief Is the Thing with Feathers is the story of a man and his two sons grieving after the sudden death of the wife and mother. It reads as a prose poem more than a novel: an attempt to describe, with matter-of-fact lyricism, the many different shapes in which human emotions wind around a sudden and unspeakable disaster. The accuracy of observation, tuned to the strangest, least expected detail of the work of grief, was stunning. So was the language, in which pain took on a plethora of forms — from playful self-mockery, through bitter irony, to spells of straightforward gravity. In all, it was a book as honest as it was ingenious. A beautiful realization of a rare genre, the biography of a feeling, which reminded one of Stendhal’s “crystallization” and “decrystallization” of love.

The premise of Lanny seems at first glance to be a logical follow-up. Jolie and Robert, an English couple, have moved from London to a village within commuting distance to provide their son Lanny with fresh air and a good primary school. The father takes the train each morning to his City job in asset management, and the mother, who has recently swapped an acting career for writing, stays at home to work on a thriller. She also arranges for her son to have free art lessons with the eccentric local artist, Pete, and allows the child to roam freely after school. One evening, Lanny disappears, and the whole village starts looking for him.

All one needs in order to understand human nature is one village, Porter seems to be saying in the style of Agatha Christie. His ambition is clearly to delve into the soul of each of the many characters who take turns at relating events and communicating their feelings.

What is it, though, that we are actually shown?

Take Lanny. We hear from the other characters that he’s an amazing, extraordinary child: “away with the fairies,” “carrying his strange brain around,” “almost possessed.” This is repeated so often in the book that we almost take it for granted. If we look closely, however, what we actually see is just a boy who sings to himself, enjoys painting, builds dens in the woods, and talks to imaginary beings hidden in trees. Now, wouldn’t that be pretty much every child if we take away their iPad and PlayStation?

Lanny might sound, on the surface, like the happy result of the middle-class dream of an artsy upbringing, but there isn’t enough in him to amaze us as he amazes other characters. Worse yet, he appears to amaze the novel’s narrative voice. This undermines the reader’s ability to suspend disbelief. In short, we simply find it hard to trust what we are told.

And this turns out to be a recurrent problem throughout the book.

When it speaks of the village and its history, the voice’s tone is one of amused astonishment. But what is so special about the village that we should be so constantly astonished? A mythical character is introduced: Dead Papa Toothwort, a sort of omniscient presence, the village’s Green Man, who has seen it all, known it all, and is now listening. His role in the novel, apart from weaving together snippets of conversations (and pulling the book toward the tricky genre of magical realism), is to give momentum to the events, place them in some perennial pattern of village history. But what is perennial about this particular plot if we look at it from the perspective of some 2,000 years of history, as we are asked to do? Hard to say. It is more as if the author is reaching after something profound to power his writing, a poetic intensity of the kind that drove his first book so well. This time, however, the subject will not supply it.

Or take Jolie. The book expects us to sympathize with her, but there’s hardly anything there to sympathize with. Even the promising fact of her being a former actress and a first-time writer doesn't add much, apart from explaining why she works from home. When Porter tries to make her more profound, in her newly found fascination with the artist Pete, all she does is commit an annoying contemporary bourgeois cliché: the idealization of the artist and the eccentric. Here she is dreaming of dinner parties with him instead of her City husband: “Dinners where nobody speaks for a while, where we talk about books we’ve read, and someone falls asleep and it’s not weird or eccentric, it’s just slow and kind, unhurried and accepting.” Yeah, and the coffee is fair trade, and the bread Lithuanian. She only becomes really alive when drama strikes: “And I saw myself, as it was beginning. A woman about to be crushed. Beginning to be rebuilt as a model of failure and agony.” This is when she steps out of the lukewarm temperature of the novel, in which she would need a lot more depth of character to be convincing, and into the heat of a poem.

The first half of the book presents the setup and introduces the characters, while the drama only unravels in the second half. This is where Lanny improves. The rising tension brings out strong feelings in the main characters, an emotional range in which Porter feels at home, and which, finally, we occasionally share. It also elicits some amusing remarks from the broader population: “There are several hundred people, at this very second, casting aspersions on their parenting. Judging. Telling stories. I don’t think you wanna be that person do you?” But most of the reactions are foreseeable, sometimes to the extent that one gets impatient at having to read them. The petit-bourgeois newcomer Mrs. Larton and her petit-bourgeois nastiness. The tabloids and their tabloidness. The people working at the pub and their interest in selling beer rather than in their fellow human beings. The book comes closest to a full, novelistic character in the depiction of the father, who watches porn in the bathroom, makes a thoroughly selfish choice of morning train, and finds himself not really missing his son when the latter disappears. However, he too is mostly a type, not a person, only a little bit more interesting than the rest.

In the end, it is hard to call the book accomplished in its psychological or social portraiture. The disparity between the meagerness of the world shown and the flamboyant tone used to talk about it can be irritating. It is as if the novelistic subject and scope of interest, which seemed so logical, didn’t prove to be the right step after all for an author who really has the heart for a prose poem. Yet there is one area in which Lanny succeeds: its political ambition. If we read it as a collection of the most generic contemporary British types, and not an attempt at poetry or fresh social or psychological insight, a canny depiction of the sociopolitical condition of post-Brexit Britain emerges. Some of the snatches of village talk would certainly amuse a student of the contemporary British mind. “Iranian or something,” “coming for our jobs,” “his dog's called Sir Walter Raleigh.” The Britain torn between tolerance and openness — here represented (rather unoriginally, but that’s fine in a political satire) by the arty London type (the mother), the sweet village type (Peggy), and the artistic type (Pete) — and the deeply rooted hostility toward newcomers, vigorously incorporated in the ultra-conservative Mrs. Larton, who grotesquely overdoes the sin of xenophobic vanity. Hostility not only to foreigners — as in “what next Polish adverts in the parish mag” — but even to fellow Brits who have dared to move in from 50 miles away, or even those who dare to be young.

Yes, this is the best thing in Lanny. The battle between the, “I despise your smell of fetid carpets and toast; Silk Cut, marmalade, gas and antiques. I feel sick just thinking about your yellow-stained lamb’s-ear fuzzy upper lip, your heirloom rings stacked on your Churchillian pug-knuckles, the inside of your huge dank house, your weighty silver biro in your splotched hand as you scratch away at the puzzles in your evil newspaper,” and the, “What if we, the generation of people who remember the war, actually told these frightful, entitled young people that this is a country we fought for, that you cannot simply buy a sense of belonging on your mobile phone.” Tut tut, indeed. It might not be an outstandingly profound picture, but it is often quite funny and rings true.

¤

LARB Contributor

Magdalena Miecznicka is a Polish journalist, critic, playwright, and novelist currently based in London. She holds degrees from Warsaw University and the University of Paris III-Sorbonne Nouvelle, and has studied under the auspices of the Open Society Foundations at Kalamazoo College in Michigan. She worked at the Institute of Literary Research of the Polish Academy of Sciences and Humanities as an assistant in the Historical Poetics Laboratory. Her academic research focused primarily on the work of Witold Gombrowicz. She is the author of two novels and several plays in Polish and is working on her first novel in English.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Futuristic Technology of an Alternate Past: Ian McEwan’s “Machines Like Me”

McEwan seems ultimately to have wanted to write a science fiction novel, but he couches it in his old historical upholstery.

Whatever You Say … Say Nothing: An Interview with Patrick Radden Keefe

Benedict Cosgrove interviews Patrick Radden Keefe, author of “Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!