Exploring Racial Imaginaries in Soviet Visual Culture

Yevgeniy Fiks’s new book offers a rare glimpse into the Soviet Union’s ideological views on race and Blackness.

By Sarah ValentineFebruary 7, 2022

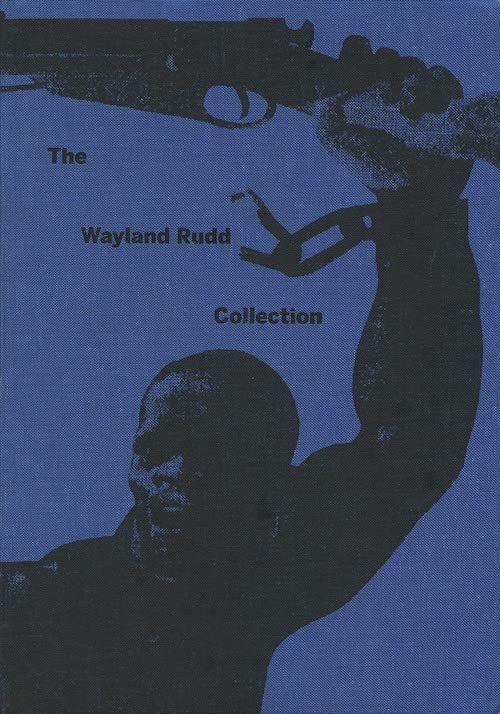

The Wayland Rudd Collection by Yevgeniy Fiks. Ugly Duckling Presse. 264 pages.

YEVGENIY FIKS’S NEW BOOK, The Wayland Rudd Collection, a gathering of anti-imperialist propaganda posters from the 1920s to the 1980s, offers a rare glimpse into the Soviet Union’s ideological views on race and Blackness. The images, which depict Black bodies in service of an international socialist narrative, are graphic. The Soviet Union’s ideological enemies with the worst histories of racial terror — the United States, South Africa, and Great Britain — are shown committing heinous acts, some depicted with cartoonish satire, others with a horrifying photorealism. In the more heroic images, showing workers constructing the socialist future or raising tomorrow’s children, Black bodies are celebrated.

A Russian émigré artist, Fiks developed an interest in the connections between Soviet and American communism. His research revealed a strong presence of African Americans in the Communist Party in the United States and direct engagement with antiracism in the Soviet Union. Pictures told the story. In 2010, he began collecting images of Black Africans and African Americans in Soviet art and culture. Soviet propaganda posters proved the richest repository of historical and ideological narratives, showing the intersections of art and race. Fiks’s personal archive now consists of over 300 images, 20 percent of which are objects like postcards and matchboxes, the other 80 percent being high-quality digital images of original Soviet art posters. In recent years, Fiks has drawn on this collection for art exhibitions and now for this book.

Fiks named the collection in honor of Wayland Rudd (1900–1952), an African American actor who left the United States in 1932 to pursue a career in the Soviet Union. Rudd’s likeness appears in several of the posters, implying that he either modeled for the artists or that they gained access to his image from photographs or playbills. Rudd served as the face of the “Negro” in more ways than one. His work in Soviet theater and film provided otherwise scarce representations of Africans and African Americans to Soviet audiences.

In the introduction, Fiks addresses the drastic changes our social and political realities have undergone since the project’s inception. He acknowledges that the collection may seem far removed from the urgencies of the Black Lives Matter movement and the protests for freedom in the post-Soviet Russian Federation. But as the materials gathered in the book show, the images, despite (or perhaps because of) their historical remove, are still startlingly relevant in that we get to see what has changed, for better or worse, in the realm of international racial equality, and what has not.

Ugly Duckling Presse has created a beautiful book. The volume is a cross between an art book, with full-color glossy renderings of images from the collection, and an anthology of essays, interviews, and other writings that respond to the images. It is the size of a hardback novel but feels heavy enough in the hand that you anticipate more than a reading experience. The cloth covers are strong enough to protect what’s inside, and the soft binding means that you will not have to crack the book’s spine to get a clear view of the art. The essays and images have equal importance, but the arrangement of the volume, with the art pieces beginning and ending the book, allows the collection itself has the last word.

Fiks provides the introduction and two essays. Then 15 other contributors offer their insights: Kate Baldwin, Jonathan Flatley, Joy Gleason Carew, Lewis Gordon, Raquel Greene, Douglas Kearney, Christina Kiaer, Maxim Matusevich, Denise Milstein, Vladimir Paperny, MaryLouise Patterson, Meredith Roman, Jonathan Shandell, Christopher Stackhouse, and Marina Temkina. Each piece provides a unique lens through which to view the artworks and Rudd himself.

The first section, “Lives,” delves into Wayland Rudd’s life and the experience of other African Americans in the USSR. In the opening interview, MaryLouise Patterson discusses her experience in the 1960s attending Peoples’ Friendship University in Moscow, a school geared for students from currently and formerly colonized countries that also recognized African Americans as a colonized people. Patterson describes the electricity of the political environment, with demonstrations over the Cuban Missile Crisis and the murder of Patrice Lumumba (for whom the university was renamed), and her feeling that she was part of an emerging new world order. She says she did not experience discrimination at the university and characterizes the years she spent there as the “best six contiguous years of my adult life.”

Patterson’s perspective is valuable because she provides a framework for understanding race and racism, or its lack, in the Soviet Union at that time. Given its geographic position, Russia did not participate in the Atlantic or Mediterranean slave trade, and while a sparse overland trade in slaves did exist, it did not become a significant industry, much less the backbone of the economy, as it did in Europe and the United States. For enslaved labor, Imperial Russia relied until 1861 on the institution of serfdom, wherein Russian peasants were tied to land owned by the gentry. Instead of selling enslaved individuals, the land was bought and sold, and the serfs along with it.

This is not to say that the only historical contact Russians could have had with Black and African peoples was through oppression. Traders, merchants, performers, sailors, and foreign dignitaries, among others, provided opportunities for encounter. Alexander Pushkin, the father of Russian poetry, famously had an African great-grandfather: an adopted godson of Peter the Great, he became a naval engineer and married into the Russian upper class, creating a legacy and mythos that resonates through Russian culture.

Delineating Russia’s history with Black peoples is important to understanding The Wayland Rudd Collection. In the 1930s and ’40s when Rudd lived in the Soviet Union, people of African descent were not assumed to be members of a lower social caste, as they were in the United States. There was no African diasporic population in Russia or the Soviet republics. Precisely because of this lack of historical and contemporary presence, Black and African people’s place in Soviet society was unclear. The Soviet propaganda machine used this to its advantage, carving out a well-defined narrative in which Africans and African Americans stood alongside white Russians and other peoples of the world as agents of socialism.

Rudd was part of a group of more than 20 African Americans, including the poet Langston Hughes and the artist Lloyd Patterson, who traveled to the Soviet Union in 1932 to work on an international film project called Black and White, about African American oppression in the South. The project was ultimately cancelled (though a short, animated version of the film was produced), and most of the group’s members returned to the United States. Rudd, however, stayed.

That decision determined the course of his life. In the Soviet Union, Rudd had a successful acting career on stage and in film, an opportunity denied him in the Jim Crow United States. By the 1950s, Rudd had become the “father” of the Black expatriate community in Moscow. When he passed away in 1952, his body lay in state with full Soviet honors in the Union Hall of the Theatrical Trade Union. Rudd’s success in the Soviet Union underscores the full horror of the repression that he and other African Americans faced in the United States. Stalin’s Russia was far from a utopia, but Rudd found there a society where his talent could prosper.

The second section of the book, “Representations,” opens with a powerful prose and graphic poem by Douglas Kearney that juxtaposes two images — one a propaganda image of a Black man hanging from a noose held by the Statue of Liberty, the other an infamous photograph of white men standing beneath the body of a Black man they have lynched. Kearney’s poem asks: “Do it feels this good being used?” As we often see in the media today, the Soviet posters, though they perform antiracism, also replicate the violence inflicted on Black bodies. Kearney writes: “To be used thus is to be both propped up and prop […] an object not meant to object.”

The essays in this section continue to deconstruct the posters’ messages. Fiks’s piece “Sorting through the Wayland Rudd Collection” treats clusters of symbols in the anti-American propaganda, such as the Slavic/Caucasian male (who features as the leader in many of the posters), the Statue of Liberty, nooses, dollar signs, and shackles. He also looks at the victims, mothers, heroic fighters, and colonial oppressors in the posters aimed at building African international socialism. And he points out that the racial stereotyping of the Black characters is at odds with the posters’ anti-imperialist, antiracist messages.

Jonathan Flatley’s essay discusses early Soviet campaigns against US racism. Flatley writes that the Comintern’s 1928 Congress included the “Black Belt Thesis,” which stated that “the Party must come out openly and unreservedly for the right of the Negroes to national self-determination in the southern states, where the Negroes form the majority of the population.” The thesis reasoned that American Blacks should rule politically in the areas where they were the majority. He writes that the Comintern organized training and education programs on Jim Crow and segregation, and created newspapers like The Southern Worker and The Negro Worker, which reported on the Black struggle. It would be interesting to know what impact, if any, these efforts had on the lives of African Americans in the United States — whether there was genuine outreach or if the efforts focused more on educating the Soviet population. Either way, Flatley has excavated a forgotten piece of history that invites deeper exploration.

The third section, “Reflections,” puts the collection in contemporary and historical context. Fiks includes some images from a 2013–’14 exhibition of the Wayland Rudd Collection at the Winkleman Gallery in New York, for which he asked 13 contemporary visual artists to contribute original work. Alexey Katalkin’s painting Searchlight superimposes a large beam of light, reminiscent of that in V. Boldyrev’s 1969 poster “The Great Lenin Lit the Way for Us,” onto traditional Uzbek fabric. As Fiks notes, the painting points up the “contradictions between the anti-racist, internationalist, anti-colonial, and anti-imperialist stances of Soviet propaganda [and] Soviet-era colonialism and imperialism towards Soviet territories of Central Asia.” Katalkin’s painting also comments on present-day Russian racism toward immigrants from Central Asia, including Uzbekistan.

It is a stretch to say that Stalin, who ruled the Soviet Union from 1924 to 1953, was an early advocate of Black Lives Matter. After all, no lives mattered to Stalin except those that could consolidate his power. His Great Purge and pogroms rank alongside the Holocaust as major acts of genocide and antisemitism in the 20th century. In the introduction, Fiks notes that the posters in the collection amount to a kind of “whataboutism,” messages designed to distract from criticism of the Soviet Union by focusing on the evils of its enemies.

In her essay “Anti-Racist Aspirations and Artifacts,” Meredith Roman discusses the importance the promise of physical safety played in the decisions of African Americans like Rudd to emigrate to the Soviet Union, despite the risks and uncertainties such a drastic move entailed. Roman contends that part of the value of the Wayland Rudd Collection is that it proves the propaganda campaign’s effectiveness. The USSR advertised itself as a safe haven for African Americans and others who suffered racist and imperialist persecution, and at least for some, the promise held true.

¤

LARB Contributor

Sarah Valentine is the author of the memoir When I Was White (St. Martin’s Press, 2019). She holds a PhD in Russian literature from Princeton University and has taught literature and creative writing at UCLA, UC Riverside, and Northwestern University.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“The Doctor of Cult Urology”: A Conversation with Vladimir Paperny

Sasha Razor interviews bilingual author, designer, architectural historian, culturologist, and video journalist Vladimir Paperny.

The Cold War Industry: On Louis Menand’s “The Free World” and Anne Searcy’s “Ballet in the Cold War”

Harlow Robinson weighs “The Free World” by Louis Menand against “Ballet in the Cold War” by Anne Searcy.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!