“The Doctor of Cult Urology”: A Conversation with Vladimir Paperny

Sasha Razor interviews bilingual author, designer, architectural historian, culturologist, and video journalist Vladimir Paperny.

By Sasha RazorJune 27, 2021

IN THE 1980s, Moscow-born Angeleno Vladimir Paperny did a rare thing — he turned his undefended dissertation into an academic best seller. His iconic study Architecture in the Age of Stalin: Culture Two (1985) changed the way readers and scholars viewed not only the Soviet Union’s architectural legacy but its cultural development as a whole. Yet Paperny has worn many hats: bilingual author, designer, architectural historian, culturologist, video journalist, and university professor. In 1981, he immigrated to California with his family, and in 1985, his book was published by Ardis. In subsequent years, the concept of “Culture Two,” which encapsulates the semiotics and stylistics of totalitarianism, has often been used in the field of visual studies. At the time of his arrival, Southern California was the site of a burgeoning Soviet émigré community and a hotbed of Slavic studies. Visits by Soviet authors in exile were also not uncommon, and Paperny arrived not long after the seminal conference “Russian Literature in Emigration: The Third Wave,” organized by Olga Matich and Michael Henry Heim. Since then, he has become a Californian-Russian writer himself, authoring several collections of short stories and essays, including Mos Angeles (2004) and Mos Angeles-2 (2009), Mos Angeles Selected (2018), Fuck Context (2011), Culture 3: How to Stop the Pendulum? (2012), and a memoir about his father, a famed literary scholar, Zinovy Paperny: Homo Ludens (2019). His recent Russian novel, The Schultz Archive (2020), presents readers with a daringly personal account of the times that shaped three generations of the Paperny family.

I interviewed Vladimir Paperny on Zoom about his new novel and writing practice, memories of Moscow at midcentury and California in the 1980s, as well as his take on contemporary Russia. We spoke in Russian, and the interview has been translated and edited for clarity.

¤

SASHA RAZOR: You worked as a designer in Los Angeles for many years, moved into academia, and now your Russian novel is out and even made it on to the short list of the influential Big Book award. What distinction do you draw between academic and creative work?

VLADIMIR PAPERNY: I have a great story about this. When I was a kid, I always pretended to be someone else, or rather, I presented myself as someone else — an actor or musician or cadet in military school. Later, I presented myself as an artist and joined the Stroganov Moscow State Academy of Arts and Industry with virtually no drawing or painting skills, despite the fact that I loved both growing up. It did not go too well at first, and I was a step away from expulsion, but in the end, my teachers suddenly said: “Look at that drawing. We’re going to keep it in the archives! Look at that sculpture, it took our breath away!” My undergraduate degree says I’m an artist-constructor, which was the Russian term for designer at that time. After graduation and a few years of pretending to be an industrial designer, I started pretending that I was a theorist, working in the sociology department of the Institute of Theory and History of Architecture. I ended up writing a dissertation that dealt with many “forbidden” subjects, which meant it couldn’t be defended in the Soviet Union.

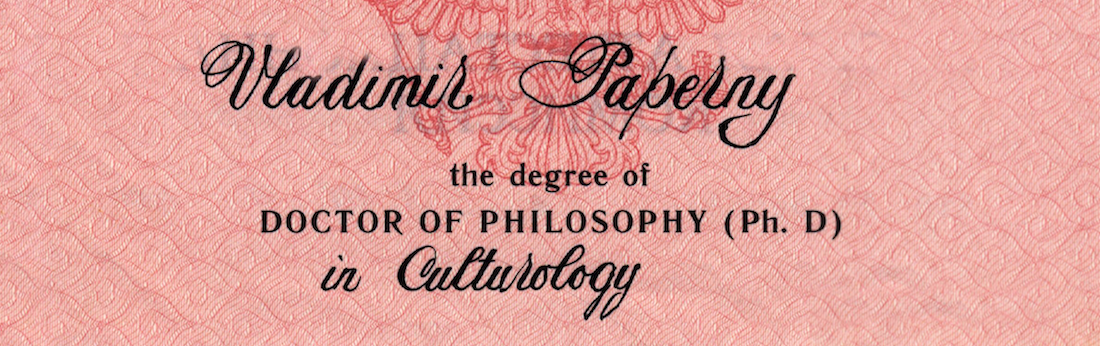

In California, too, life was a constant transition from one thing to another. I couldn’t teach at universities because I didn’t have a PhD diploma. So, I picked up my design career, and it was the most tenuous possible pretense. As traveling back to Moscow became possible, I had the opportunity to defend my dissertation 20 years later and received this fantastic certificate, which I can’t stop showing people. It says I am a Doctor of Culturology, but my spellcheck keeps saying Doctor of Cult Urology. This gave me the opportunity to join the UCLA faculty. All in all, my view of my own biography can be summarized as follows: I am a cyclical person who rotates between writing and visual arts. This cyclicality is manifested in my dissertation and in my novel The Schultz Archive. And I am still working in design because Russian novels usually don’t pay well.

Could you elaborate on that? How does The Schultz Archive relate to Culture Two?

I started writing the novel back in 1972, and I started my dissertation in 1975. They developed concurrently, and, in fact, there was no wall between them. Essentially, they are about the same thing and belong together. I am interested in the era that shaped my parents, grandparents, and me. In my dissertation, I abstained from personal digressions and only made a few remarks to the effect that “my father Zinovy Paperny wrote so and so,” but I let myself loose in the novel.

Initially, I was told by a good friend in Moscow to write a memoir instead of a novel because “people are more interested in reading about real life.” Yet I wasn’t able to follow her advice for various reasons, not the least of which had to do with legal and ethical issues. Having begun the book as fiction, I wasn’t so concerned with accuracy and altered both the names and situations as I went. In fact, I tried to move as far away from reality as possible, swapping names, professions, and locations — changing everything that could have been changed. There are a few stretches of dialogue that are documentary, but when people ask me to identify my protagonists, I absolutely refuse to do so.

You drafted your dissertation, which later became Culture Two, like Nabokov, on index cards. The title of your novel features the word “archive,” and its chapters contain the protagonist’s diary. Could you talk about your writing processes?

For my dissertation, the cards were convenient and easy to categorize and rearrange. Once I had assembled all the parts in a particular order, my thesis was complete, and I just had to pen it. In the novel, however, I worked with stacks of notebooks from my manuscript archive. Some of these texts had already been published, while others were waiting for their moment. I dreamed of writing a novel one day, and as the lockdown started, I realized now was the perfect time.

Regarding my archive, I tend to hoard all kinds of unnecessary records, and my family suffers greatly due to this. In addition to my own papers, there are also my mother’s documents and parts of my father’s library. I can show you my journal, which I’ve been keeping since 1964. It is swollen from multiple inserts and additions. Each year, I write an entry on a page assigned to a particular date of the month. I discovered that certain records repeat themselves time and again and that exact phrases may be reproduced word for word 20 years apart. I’ve incorporated this autobiographical feature into my novel.

Your main character, Sasha Schultz, is an architect. Does he have literary precursors?

As I was working, I didn’t think about any other novels built around an architect, but when people started asking me this question, I discovered Dickens and other writers as predecessors. Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, for instance, features architect Howard Roark, someone I find as disagreeable as the author herself, so I won’t make any comparisons here. What is it about me and architects? I’ve had an interest in architecture, studied it, and lived in two cities with a great deal of interesting architecture, Moscow and Los Angeles. Also relevant to this story is that my mother always wanted to be an architect, but it never worked out, so she wanted me to become one instead. She always bought me calendars when I was a kid, with objects to be cut out and glued together, like cars, steam locomotives, or ships, and I loved this. Whenever I had a sore throat (back then, children were supposed to stay home for several weeks), my mother stayed with me, and we cut stuff out for hours and hours. Those skills later came in handy when I became an art student in Moscow or had my own paper sculpture business here in the US.

Despite your reluctance to identify your characters, can we ask you to make an exception? Who served as a prototype for the African American family you portray in your novel?

Yes, Wayland Rudd was an actor and singer from New York who moved to the Soviet Union in the late 1930s and eventually married a white American pianist named Lorita Marksity. Her father, a Serb, fell in love with Marx so profoundly that he gave himself a new last name. So Marksity was an invented last name, and Lolita was the stage name the daughter went by. Her father brought her to the USSR at the age of 16. On the way, somewhere in Europe, Vladimir Horowitz caught a glimpse of her performance and then warned them not to go, but they went anyway. Lolita met Wayland during the war and married him. He died several years later, leaving her with two kids in Moscow. The kids, of course, couldn’t even leave the house without everyone staring at them, eager to shake their hands. And there had always been a steady crowd of people around their father. Despite my best efforts to embellish these details, I’m no Midas. I also authored one of the chapters in Wayland Rudd’s biography, which will be published shortly by Ugly Duckling Presse under the title The Wayland Rudd Collection. I was close to the Rudd family and have photos and videos in my archive.

Let’s move our conversation to America. During Nikita Khrushchev’s visit to Los Angeles, he wanted to see Disneyland but never made it. On the other hand, you landed in Anaheim and have been there countless times. What did you think of American architecture back in the ’80s, after Moscow and Rome, and how has it changed over time?

I’m sorry to say this, but my first encounter with America was a great disappointment to me. Our plane from Rome landed late at night, and the Jewish Family Service picked us up and took us to an apartment they had rented in Orange County. After the flight, we were in a haze, and I asked on the freeway where the city was as I didn’t understand anything. I was told that this was the city, and they laughed like I was some weirdo. The only thing I liked was the apartment. There was a modernist aspect to the building and interior, and I was deprived of that in Moscow. Disneyland and Anaheim, however, looked like cheap movie sets to me. After three months in Rome, the contrast was striking. I changed my mind about Disneyland after talking with my colleague, the art historian John Bowlt, who was very kind and helped us upon arrival. Learning about John’s enthusiasm for Disneyland, I realized I was still a modernist, not capable of appreciating the postmodern city.

You moved to Los Angeles in 1981, shortly after the “Russian Literature in Emigration: The Third Wave” conference was held here. Do you personally know any writers from this group, and did you meet any of them in L.A.?

Of course, I knew Olga Matich and the late Michael Heim, who, with his wife Priscilla, helped us enormously from the start. I even made a documentary about Olga and her dramatic biography for Russian television. The novelist Sasha Sokolov lived in Los Angeles for quite some time, and our paths crossed at parties and social gatherings. Additionally, I made a documentary film about Yuz Aleshkovsky and visited him in Connecticut. Vasily Aksyonov was also at the conference, and I spoke with him several times when he was in town.

But there is one poet from that conference whom I knew really well: the dissident Nahum Korzhavin. He was my parents’ friend and often visited us back in Moscow: my father read his parodies, Korzhavin read his poems. Everyone called him Emka. He had been in love with my mother, Karelia Ozerova, all his life and wrote a wonderful poem about Los Angeles, dedicating it to her. We lived on different coasts, but he treated me like family and scolded me for what I published in Panorama, the L.A.-based Russian newspaper. Korzhavin, like many Soviet immigrants, was politically conservative. I managed to keep our relationship free of polemics and respected him as a poet.

I have another story about Nahum. His wife, Lyubov, was a philologist, and when a job opened up at the USC Slavic Department, she decided to apply. At the time, Olga Matich and Alexander Zholkovsky were there. Korzhavin, hoping to help, began to emphasize his affection for Olga, which came across as a bit artificial. One day, my phone rings. I pick it up and hear him swearing in Russian: “Unfortunately, fucking unfortunately!” Taken aback, I ask: “What’s up, Emka?” He explains: “Tell them … your Zholkovsky and Matich … tell them that they could have used the telephone instead of sending a rejection letter by mail. Unfortunately, fucking unfortunately!” This phrase has entered our family lexicon.

My colleagues sometimes refer to this story on similar occasions, so I am pleased to hear it from the horse’s mouth. What’s your next project?

The next project I’m working on is also based on an archive, which belongs to the late film scholar Maya Turovskaya, who passed away in Munich in 2019. We worked with Maya on a comparison of American and Soviet cinema in the 1930s and 1940s. We first received a joint grant together from the Kennan Institute in DC and then met in Berlin to continue our work. Shortly before she died, Maya sent me her entire archive on this topic, saying, “The ball is in your court.” I wrote this book based on our conversations and her papers. It contains our collaboration story, her texts, my own texts, and an analysis of over 30 films. I feel a moral obligation to get this published.

In Culture Two, you analyze two cultural paradigms, the deconstructive youthful avant-garde of the 1920s and monumental Stalinism of the 1930s and beyond. How do you look at Russia over the past decade? What cultural paradigm predominates, or has Russia entered a new era?

Every time I went to Moscow over the last 10 years, my friends would ask: “Is this Culture Two already or not?” In my view, the answer is obvious, and I even assembled a table comparing the resolutions of the late 1930s with those of the early 2010s, which duplicated them nearly literally: the decrees on foreign agents, on homosexuality, on volunteer organizations, and many more. I even jokingly observed that someone in the Duma had been rereading old documents. That’s unlikely to be the case, and what we’re presumably experiencing these days is some kind of cyclical cultural mechanism playing out once again. The activation of this mechanism, however, occurs at a new technological stage. From a social and political standpoint, this is a different country, equipped with the internet and digital surveillance. Although the technology of terror has changed completely, the terror itself has not become fundamentally different. Its aesthetics are rather traditional and date back to the tsarist secret police. However, since the borders are no longer sealed, the atmosphere in the country is not the same. Those who don’t like the government are free to leave, and many do. Those who can’t have to shift their views sharply — either to the left or the right. When dealing with the state, they only have two options: fight it, suffer, and be beaten by the police, or disregard your own beliefs and make peace with conformity. It is almost impossible to remain a professional in today’s Russia without serving the government or joining the opposition. The loopholes are tiny, and as they continue to shrink, keeping out of politics in an ivory tower is becoming increasingly difficult.

¤

LARB Contributor

Sasha Razor holds a PhD in Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Languages and Cultures from UCLA. Her dissertation focused on the screenplays of Russian prose authors in the 1920s and 1930s.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“This Decadent Western Thing”: Joanna Stingray on the Soviet Underground Rock Scene

The L.A. rocker on her experiences in the underground rock scene in pre-glasnost Russia.

The Only One Left: A Conversation with James Lloydovich Patterson About Grigori Aleksandrov’s “Circus”

Sasha Razor interviews James Lloydovich Patterson, the son of an African American father and a Soviet mother who became a Soviet actor and author.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!