Encountering Weegee: On Christopher Bonanos’s “Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous”

Geoff Nicholson exposes himself to “Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous” by Christopher Bonanos.

By Geoff NicholsonAugust 6, 2018

Flash by Christopher Bonanos. Henry Holt and Co.. 400 pages.

When Weegee Met Judith

THE BEST COMMENT on Weegee belongs to Judith Malina, of the Living Theater, who knew Weegee in Greenwich Village. She said, “He wanted to see the soul of the person. He wanted to see the essence of the person. And he certainly wanted to see the tits of the person.” The fact that she found this comical rather than objectionable suggests that Weegee’s lechery was always essentially laughable.

She made those remarks in an interview with Christopher Bonanos for his recent book, Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous. The only disappointment is that this comes in a section where Bonanos is fretting over whether Weegee was “an artist or an artisan.” Didn’t we stop asking, “But is it art?” about 50 years ago? Evidently, some of us didn’t.

When Usher Met America

In Cecil Beaton and Gail Buckland’s The Magic Image: The Genius of Photography from 1839 to the Present Day (1975), you’ll find a reference to a photographer named “Arthur H. Fellig (‘Weejee’)” — an error that surely can’t quite be explained by sloppy proofreading. Professional contempt on Beaton’s part seems a possibility.

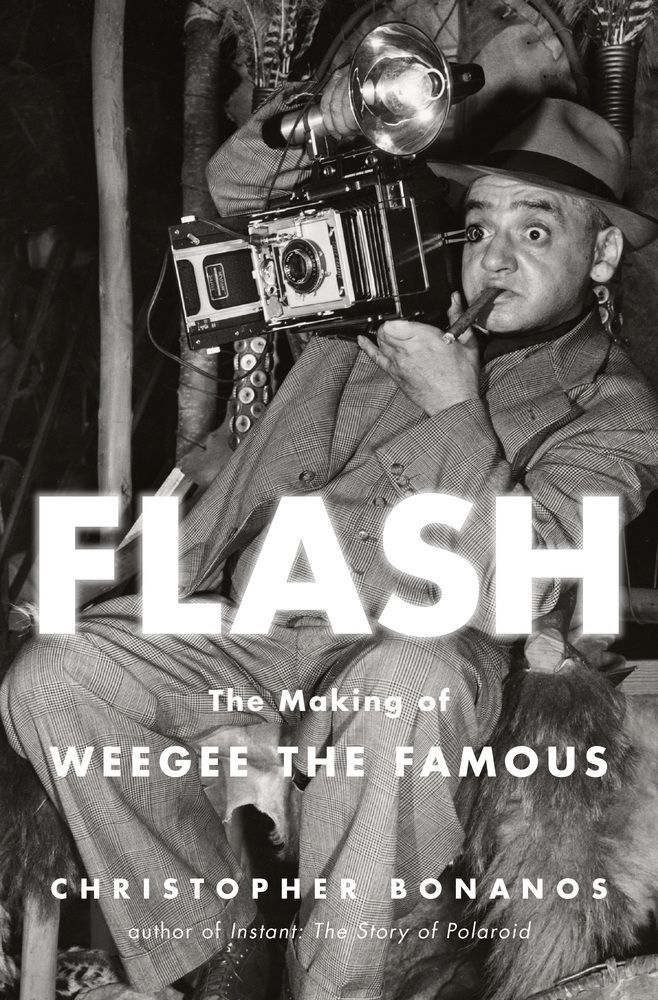

Be that as it may, we learn that Weejee (sic), “was a raucous self-advertising, cigar-chewing character, living alone in a room piled to the ceiling with his pictures of the alleyways and the dark side-streets of New York, the crime, robbery, murders, fires, and the drop-jawed crowds who came for excitement to see these lurid things,” which is a good enough summary as far as it goes.

“Weegee,” of course, was an invented name, a conflation of squeegee (he had been a squeegee boy in a photo lab) and Ouija, as in the board, an indication that he had a supposedly supernatural ability to know where the action was, and to get there and capture it on film. Having a police radio certainly helped.

But even the “real” name, Arthur Fellig, was an invention of sorts. He was born Usher Fellig, in 1899, in Zolochiv, then part of Austria-Hungary, now part of Ukraine. His father arrived in New York in 1906, the rest of the family followed in 1909, and Usher became Arthur as part of his assimilation.

Before and after him, there’s a considerable history of photographers changing, often Anglicizing, their names — Robert Capa, Man Ray, Peter Berlin. There’s also a continuing tradition of the single name photographer: Nadar, Brassaï, Rankin, Hiromix. It reinforces the brand.

Weegee instinctively knew all about branding, even if he wouldn’t have called it that, and he started referring to himself as “Weegee The Famous” in 1938 or so, when his fame was decidedly limited. Self-deprecation was not part of his deal. Bonanos writes,

Weegee was the one who went on talk shows, raced to burning tenement to beat the competition, got assignments that paid hundreds or even thousands of dollars; Arthur Fellig did not. Was that guy he created immodest? Self-aggrandizing? Pushy? Irritating, sometimes? You bet he was. This was New York, and he was in the newspaper business. Modesty was for suckers.

I don’t know that I’m entirely persuaded by this separation of the “real” man from his created persona. Surely they both ended up old, frail, and desperate, living in a depressing little room in Manhattan — although Bonanos does have a quotation from an interview in which Weegee speaks of himself as a Jekyll and Hyde character.

When Weegee Met Success

Although Weegee proclaimed his own fame, and indeed genius, to the end of his life, there’s a pretty good argument that he only produced really great work for about a decade, between 1935 and 1945. He did indeed become famous at this time. Those are the glory years, when he took photographs of bloodied corpses lying on the sidewalk, hideously crashed cars, firemen with ice caked on their helmets, transvestites, perp walks, and paddy wagons.

Weegee also understood the importance of a good selling line. There are photographs, very probably staged, that show him hammering out captions, or titles, on a typewriter set up in the trunk of his car. The words added value to the pictures.

A photograph titled “Their First Murder” shows a small crowd of people, most of them children, and although a few of them look upset, most look amused or entertained. If not for the caption, you might think they were watching a circus act. Another, titled “I Cried When I Took This Picture,” shows two women, one old, one young, clinging to each other in the aftermath of a fire. From the picture itself we can’t tell who they are and what they’ve lost, but we happen to know that the older woman is a Mrs. Henrietta Torres, who is clinging to her daughter, having just discovered that she’s lost her other daughter and a son in the conflagration. It is a great and appalling photograph.

Even in this period Weegee didn’t only deal with crime scenes and disasters. As a news photographer he knew what made a good “human interest” story: shots of Coney Island, children sleeping outside on a fire escape to avoid the stifling heat of their apartment, kids cavorting in the water spraying out from a broken fire hydrant. He also took pictures at a bar called Sammy’s Bowery Follies — pictures that demonstrate his ability to make scenes of celebration look much like crime scenes. One of my very favorite Weegee images, taken at Sammy’s, is a deeply melancholy 1947 picture titled “After the Opera,” which shows a droopy-eyed, upper-class, and no doubt very drunk, opera-goer stroking a pig that sits on a table, while a rough looking young man who may well be the owner of the pig looks on inertly.

By that time, it seems that Weegee had had enough of working the crime beat. Maybe he was slowing down, maybe he was feeling his age. Mid-40s is hardly old for a photographer — there are many famously long-lived members of the profession — but perhaps he was tired of dashing through the night to capture the latest atrocity. Maybe he just wanted a change. In 1943, he’d had a very successful one-man exhibition at the Photo League in New York, titled Weegee: Murder Is My Business — didn’t I say he was good with language?

When called upon to make public utterances at this time he employed some very grim but engaging humor: “The easiest kind of job to cover was a murder because the stiff would be laying on the ground. He couldn’t get up or walk away or get temperamental. He would be good for at least two hours. At fires I had to work very fast.”

In 1945, he published a book titled Naked City — Langston Hughes gave it a good review — and it was sold to Hollywood largely on the strength of the title. Maybe Weegee saw it as the end of an era. Maybe he thought he’d done all he could with this subject matter. In 1947, he moved to Los Angeles with his new wife, who, I kid you not, was named Margaret Atwood. They lived in a few different places, none of them very far from the corner of Hollywood and Vine. Man Ray was living lower down on Vine, at the Villa Elaine, but as far as I can tell the two photographers’ paths never crossed.

When Weegee Met Hollywood, When Hollywood Met Weegee

Weegee’s time in Los Angeles was not a great success. He was just another hustler in a city of hustlers, though he did get work, doing consultancy, sometimes using his newly devised optical distortions with what he called his “Elastic Lens” for a couple of movies, even doing some bit parts. He appeared for a couple of seconds as a murder suspect in Joseph Losey’s remake of Fritz Lang’s M (1951). But after four years or so, he’d had enough of Los Angeles. Things weren’t working out either in his career or his marriage. So he headed back to New York.

Naturally enough, he’d been taking photographs the whole time — at strip clubs, at premieres, on Skid Row — and he had enough material for another book, which became Naked Hollywood, though he originally wanted to call it Land of the Zombies. Mel Harris, an advertising man and designer, helped put the book together and got his name on the cover.

Weegee’s Hollywood is a strange but fascinating place, where the sun rarely shines. Sure, many of the photographs are taken at night with flash, and many are taken indoors, but even on the street in daylight the photographs seem dark and threatening. There’s a particularly gloomy picture of Hollywood Boulevard, decorated for Christmas and soaked in rain: a touch of The Big Sleep.

Naked Hollywood contains rather more gratuitous nudity than a modern sensibility thinks necessary, including trick shots of models with three legs and three boobs. The book is often dismissed as a falling off of Weegee’s talent, and, undeniably, its images aren’t as powerful as the early crime stuff, but some of them still look great. Weegee clearly felt an ambivalence, sometimes a contempt, toward celebrity. His portraits of Errol Flynn, Henry Fonda, Hedda Hopper, and others seem very modern in their aggressiveness.

Back in New York, he kept on hustling. A dignified retirement was not in the cards, and he needed to make a living. He picked up freelance work where he could. Some elements of this were more respectable than others. He lectured, he wrote “how to” books, which are very good and give the lie to the idea that he was some sort of primitive. This is from Weegee’s Secrets of Shooting with Photoflash (1953), “as told to Mel Harris”:

The […] most important part is Anticipation. This means to know what is going to happen […] before it happens.

Observe as well as look. This sense can be developed by training yourself to be aware. When walking in the street or riding a bus, look around you, notice the people, study their movements, their faces […] When going from one place to another don’t ignore the in-between.

That strikes me as pretty good advice for anybody, not just photographers.

He continued his involvement with movies. The highlight of this period was probably working as set photographer for Dr. Strangelove (1964): he photographed the climactic pie-throwing scene, which was cut from the final movie. According to a couple of interviews given by Peter Sellers, Weegee’s voice was an inspiration for the voice of Strangelove. Roger Lewis, Sellers’s biographer, states that this is simply untrue, and to my ears Strangelove sounds nothing like Weegee, but Bonanos is content to accept the claim at face value.

Most of his movie gigs were much more low-rent, including My Seven Little Bares (1963), in which he played the judge of a beauty contest in a nudist camp, and the cosmically bizarre The ‘Imp’probable Mr. Wee Gee (1966), in which he played the lead as a photographer — he never claimed to have range. The latter is a variation on the Pygmalion story, which has the protagonist falling in love with a mannequin. It is, I suppose, an experimental movie, although more Benny Hill than Andy Warhol, which brings us to …

When Weegee Met Warhol

In February 1967, Weegee and Warhol (born Warhola, of course) met at “Caterpillar Changes,” a multimedia festival at the Cinematheque in New York. They both had films in the festival, as did Jack Smith, Harry Smith, D. A. Pennebaker, Shirley Clarke, and others. According to Bonanos, “It [the Warhol-Weegee meeting] didn’t go well. Weegee always excitable and perpetually a little awkward when he wasn’t on the job was no match for Warhol’s sunglassed detachment.” (Sunglassed?) Bonanos quotes photographer Ira Richer, who witnessed the event: “Warhol snubbed him […] It was a hurtful meeting. […] I took it in an almost morally indignant way.” Why only “almost”?

On the surface, Warhol and Weegee had plenty in common: both from East European immigrant families, both deeply connected to New York, both outsiders fascinated by fame, celebrity, and violent death. Both also had a deep and no doubt prurient interest in sexuality and other people’s sex lives, without apparently having much of one themselves.

Yet it’s just as easy to see what the two men didn’t have in common. Warhol was rock and roll, hip and cool (not least in McLuhan’s sense). Weegee wasn’t cool in any way. He was an old guy — about three decades older than Warhol — in a pork pie hat with a cigar and a badly fitting suit: he was a square. It also seems possible that Warhol simply didn’t know who Weegee was.

A Warhol diary entry from June 20, 1981, describes Chris Stein, of Blondie, showing Warhol some “1950 Weegee photographs,” whatever that might mean, and he certainly doesn’t sound familiar with the work:

[M]ost of the pictures Chris bought were of a Greenwich Village party, and you’d think you were looking at pictures of a 1980s party — it looks just the same! It’s funny that things don’t really change. I mean, people think that they change, but they don’t. There were people wearing clothes with safety pins in them and two boys kissing in a window and a woman looking on, and then it was called “Living in Greenwich Village” and now it’s called New Wave or something. But it’s the same.

This sounds to me like he could have been seeing the pictures for the first time.

About three years later, on a rainy Sunday, April 15, 1984, another entry runs: “I stayed home and did research, looking at the Weegee pictures. He’s so great. People sleeping and fires and murders and sex and violence. I want to do these kinds of pictures so much.” Maybe Warhol had just caught up with Weegee’s work then — the man himself had been dead for 16 years — though it’s an odd remark, given that Warhol had been doing his Death and Disaster series since 1962.

When Weegee Met Fanny

Finally, a curious little personal note: in the 1960s, Russian cameras made their way onto the British market. It was known as “dumping.” The story went that Russian economic planning had created huge surpluses of goods, more than could possibly be sold within the USSR. By selling them off cheaply, even below cost, the stockpiles were reduced and, perhaps more importantly, Russia acquired Western currency. That was how and why, in my early teens, I bought my first SLR — a Zenith B (the first imports had the more Russian-sounding trademark Zenit).

I had very little idea how the commercial setup worked, but Flash explains that an Englishwoman named Fanny James, along with her nephew Raphael Hyams, set up Technical and Optical Equipment Ltd., the only authorized British importer and reseller of Soviet-made radios, TVs, microscopes, and especially cameras.

In 1963, Weegee met Fanny James and she offered to cover his travel expenses in England if he promoted her company. This took him, surprisingly enough, to Coventry. While there he made a distorted image of the statue of Lady Godiva that ran in the local paper with the shout line: “It was taken with a Zenit.” Also, while in Coventry, he had his portrait taken by a photographer named Richard Sadler. The image shows him with a Zenit 3M held up to his eye, and was good enough to appear on the jacket of a recent reprint of Weegee’s autobiography.

I don’t know what Weegee really thought of Zenit cameras. Bonanaos says “they could hold their own against many German and Japanese products” — but trust me, they very definitely could not. My own Zenith was certainly a tough old thing, but if this was the state of Russian technology, it was pretty amazing they’d put a man in space, and even back then, Dr. Strangelove not withstanding, it raised doubts about their fearsome nuclear capabilities.

Until I read Flash I had no idea whatsoever that Weegee was involved with promoting the Zenit, but if the promotional work for Technical and Optical had been less successful, then maybe I’d never have bought that camera at all. In fact, sales were good enough that the company took him to Moscow on a freebie. He seems to have enjoyed everything but the food.

¤

LARB Contributor

Geoff Nicholson is a contributing editor to the Los Angeles Review of Books. His books include the novels Bleeding London and The Hollywood Dodo. His latest, The Miranda, is published in October.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Thin White Dunc: A Jaded Dandy in 1970s New York

A portrait of punk-era New York’s art and music scenes.

Multiple Exposures: On “Double Vision: The Photography of George Rodriguez”

Geoff Nicholson focuses on “Double Vision: The Photography of George Rodriguez,” edited and introduced by Josh Kun.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!