Double Lives: On Louise Brooks’s “Thirteen Women in Films”

Maya Cantu puts actress Louise Brooks’s unpublished manuscript “Thirteen Women in Films” in conversation with the recent documentary “Silent and Forgotten.”

By Maya CantuAugust 15, 2020

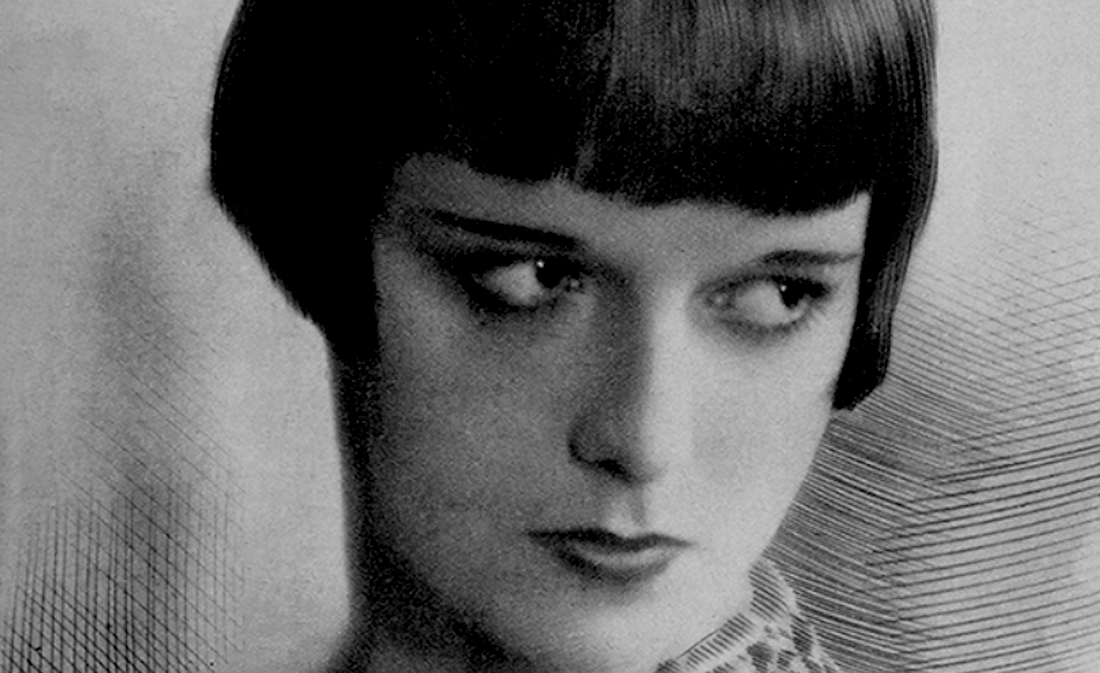

Featured image: Louise Brooks, interviewed in Lulu in Berlin, 1984

¤

IN 1966, GENTLEMEN PREFER BLONDES AUTHOR and screenwriter Anita Loos drolly paid tribute to one of the cinema’s most iconic brunettes. Loos had first been friendly with Louise Brooks “in California when she was an early-day sex kitten of the old silent films.” Almost 40 years later, in Roddy McDowall’s collection Double Exposure, Loos marveled at Brooks’s reinvention as a serious film historian and critic in Rochester, New York, where the actress had established herself in 1956:

[D]uring Louise’s middle years, when her career as a siren lay behind her, she went through a dramatic metamorphosis and turned into a highbrow. Her very image itself underwent a transformation; Louise became a spare, gray-haired and academic type of intellectual without a trace of her early seduction. […] Louise’s two widely different lives have provided her with a unique opportunity to learn the full value of female beauty as opposed to its counterpart, brains.

Though now diminished, the cultural opposition between beauty and intellect lingers. This divide has long kept Brooks, for all her acclaim as writer and critic, somewhat eclipsed by the Pandora’s Box image of Lulu, the Girl in the Black Helmet, and “the Dream Star Forever” (in the words of Jan Wahl). When the erotic cartoonist Guido Crepax used Brooks as the inspiration for his Playboy-era Valentina comics, and praised her in 1965 as a “twentieth-century myth,” Brooks quipped her appreciation: “I told him that at last I felt I could disintegrate happily in bed with my books, gin, cigarettes, coffee, bread, cheese, and apricot jam.”

All happy disintegrations aside, Brooks’s writing has endured. Roger Ebert described 1982’s Lulu in Hollywood, compiled from Brooks’s film journal essays of the 1960s, as “one of the few film books that can be called indispensable.” Brooks had been known for her profligacy in New York and Hollywood, where friends had nicknamed her Hellcat (“I like to drink and fuck,” she famously exclaimed). Exiled in the Weimar Republic Berlin evoked by Cabaret, in which Liza Minnelli took visual inspiration from Brooks, Pandora’s Box director G. W. Pabst chastised her: “Your life is exactly like Lulu’s, and you will end the same way.” Defying Pabst’s prophecy of doom, Brooks acquired an almost monastic discipline during her studies of film at the George Eastman House. Based in Rochester from 1956 to her death in 1985, Brooks developed into a prolific but fiercely self-critical writer who left behind volumes of unpublished notes, letters, and abandoned projects.

The most potentially impactful of these discarded works may have been Thirteen Women in Films, a book of essays on Hollywood icons including Joan Crawford, Gloria Swanson, Greta Garbo, and Clara Bow. Brooks’s conceptual groundwork and notes on Thirteen Women not only magnify her significant profile as a discerning feminist critic, but also frame her as a pioneer of star and celebrity studies. Over half a century later, the makers of Silent and Forgotten (2018), have picked up where Brooks left off, creating an inventive meta-documentary that borrows from Brooks’s own approach and is informed by her concept of the actress’s “double life.”

“As expendable and cheap as canned peas…”

In a midcentury era defined by its conservative gender roles, Thirteen Women in Films might have seemed the renegade spark of a rebel star. In 2020, the project seems freshly relevant, in light of a revised cultural context, and contemporary reframing of Brooks’s life, work, and image.

Working on the project between 1957 and 1963, Brooks conceived Thirteen Women as (to quote Barry Paris’s 1989 biography): “[A] study of extraordinary, uniquely beautiful women and the success with which they preserved their originality of face and personality against the vicious grindings of the producer who would reduce them to a commodity as uniform, as interchangeable, as expendable and cheap as canned peas.” Brooks’s resistance to women’s commodification in show business is no longer a countercultural sentiment. After more than a decade of popular third- and fourth-wave feminism, and three years after Harvey Weinstein’s exposure, Hollywood has never been under more pressure to interrogate its own power structures. Recent media addresses the sexual exploitation of women working in the industry, and the construction of the feminine image, as well as its intersection with the “vicious grindings” of sexism, ageism, and racism.

In critiquing contemporary power structures and beauty myths, artists and critics have turned to reexamining the icons of “Golden Age” Hollywood. Bolstered by podcasts like Karina Longworth’s You Must Remember This, this impulse has found expression in films and shows ranging from Ryan Murphy’s Feud (FX, 2017), and Murphy and Janet Mock’s Hollywood (Netflix, 2020) to Alexandra Dean’s 2017 documentary Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story, the latter of which explodes the dichotomy between beauty and brains by centralizing the actress’s scientific achievements.

In Silent and Forgotten and other works, this sea change has also shifted the portrayal of Louise Brooks from a symbol of ’20s glamour to a more fully dimensional woman. In her 2012 fictionalization of Brooks’s biography, The Chaperone, Laura Moriarty neglects neither Brooks in her maturity, nor an essential, formative fact of her early life: Brooks’s sexual molestation, at the age of nine, by a Cherryvale, Kansas, neighbor. As narrated by the Kansas matron who accompanies the teenaged Louise to New York, The Chaperone concludes with Brooks’s phoenix resurrection, after a period of drifting that Brooks looked back upon as her “hellish years,” from 1935 to 1955.

In 1955, Henri Langlois, curator of the Cinémathèque Française, set in motion the erotic apotheosis of Brooks into a “twentieth-century myth.” Langlois launched a rapturous Brooks revival among French cineastes, proclaiming: “There is no Garbo, there is no Dietrich, there is only Louise Brooks!” The “Cult of Louise Brooks” was equally fueled by Eastman House curator James Card, who offered Brooks refuge in Rochester. In her viewings at the Eastman House’s Dryden Theatre, Brooks found herself “smitten” by the Hollywood films whose commercialism she had once scorned and transfixed by their female stars. In 1957, ensconced in her Rochester apartment with her cat (“me for Suzy, gin and scribbling,” Brooks wrote to friend and author Jan Wahl), Brooks got to work on Thirteen Women in Films.

“Every word snarls at you till you get it right…”

And, yet Brooks struggled with the project. “Louise often rode a high horse to oblivion,” observes Wahl, who collected his correspondence with the star in Dear Stinkpot: Letters from Louise Brooks (2016). “She had a habit of throwing her efforts away. Thirteen Hollywood Women was not to be.” Brooks herself, in her letters to Wahl, suggests complex reasons for the demise of the project (to which Brooks gave several working titles). Idealistically devoted to the pursuit of truth in her writing, Brooks also feared rejection. In December 1961, she wrote to Wahl: “Now I must […] work up an outline of WOMEN IN FILMS. […] It isn’t the work that I dread. But I read the reviews of all the acclaimed and the reviled junk in Sat. Review and why should I add up to the destruction of forests?”

Brooks was not yet known as a writer, but she was also ahead of her time. For Brooks to have established herself as a feminist film critic and historian in the mid-1950s would have been swimming against the tides both of academia and of the emerging, masculinist auteur theory. As Paris observes of Thirteen Women in Films: “The concept was novel in every respect — and therein lay its publishing problem. […] Only NYU, UCLA, and USC had film-studies departments; there were precious few film histories or critical works in book form.” According to Barry Paris, Brooks first proposed Thirteen Women in Films in July 1957 to Charlotte Painter at the Macmillan Company, only to be rejected.

Questions remain as to what a completed Thirteen Women in Films might have looked like, and which actresses might have made the final cut. Paris identifies the women as: “Joan Crawford, Lillian Gish, Greta Garbo, Clara Bow, Gloria Swanson, Marion Davies, Norma Shearer, Joan Bennett, Pola Negri, Betty Bronson, Marlene Dietrich — and possibly as a finale — Louise Brooks herself.” Brooks, in her letters to Wahl, identifies Constance (not Joan) Bennett and Constance Talmadge as among her subjects.

Beyond its inclusions, the project raises questions about the extent of Brooks’s collaboration with James Card, whose editorial mentorship can be assumed. In his 1994 book Seductive Cinema, the Eastman House curator wrote (in a claim of co-authorship repeated in Paris’s Brooks biography): “The plan was to have each of us write a chapter on a dozen actresses whose work interested Louise; the thirteenth was Louise herself, who would write herself into each of her chapters as one who knew personally the actress under her often savage scrutiny.” In her correspondence with Wahl, Brooks does not discuss writing Thirteen Women with Card. In one June 1961 letter, written before establishing her voice in journals like Sight & Sound, Brooks scoffs over general assumptions of Card’s authorship: “But to take up writing — the beautiful and dumb — serious stuff — of course Jim writes for her…”

“And leading a double life will not confuse her…”

Whatever the level of Card’s involvement in Thirteen Women, it is hard to doubt the primacy of Brooks’s voice and perspective. Tantalizing glimpses of Thirteen Women glisten within Brooks’s 29 notebooks at the George Eastman Museum, unsealed in 2010 (25 years after Brooks’s death, per her instructions), and which I viewed as a visiting researcher in 2015. Varied in subject matter, the notebooks reveal Brooks’s comments, reflections, and quotations on topics ranging from modernist literature, to the history of “Whore Plays and Such” on the London stage. Brooks continued to research Hollywood actresses after Thirteen Women’s rejection, taking notes both from televised films, and from her viewings at the Eastman House.

Even in their raw, unedited form, Brooks’s notes vibrate with a sensuous, incisive attention to the surfaces and substances of film glamour: to details of actresses’ costumes, makeup, and the subtle, often contradictory interplay of personality and Dream Factory allure. Viewing Josef von Sternberg’s 1927 crime drama Underworld in February 1959, Brooks observes of Evelyn Brent’s performance: “[Screenwriter] Ben Hecht said he named the character ‘Feathers McCoy.’ She wears them inside.”

In her notes for Thirteen Women in Films, Brooks pushes against her own mythic construction by exploring feminine duality in the personae of other actresses: including Garbo and Dietrich. In his book Seductive Cinema, Card quotes Brooks as saying that, at the start of their careers, actresses are chosen for roles based on the close coordination of “looks and personality” with the characters as whom they are cast. The actress, producer, and audience together “create” the star; as Brooks explains of the actress’s experience, “leading a double life will not confuse her because she will see the vision she projects on the screen and know the person she is in private to be separate yet harmonious.”

This concept of the actress’s double life informs many of Brooks’s notes and writings. Describing the 1948 crime thriller Smart Woman, Brooks lauds Constance Bennett, starring as lawyer Paula Rogers, as an actress able to blend personality, voice, and gesture into an unmistakable star persona translating across media:

Her voice had the greatest and the surest emotional range I have ever heard. In medium or long shots without tears or facial contortions she had perfected the exact degree of relaxation or tension in her voice — flat indifference — warmth to a husky whisper, using almost no tonal range. […] Her walk, from the hips, stiff-kneed, slow-footed, the shading of her skull — all these things made her known at whatever distance. On TV, it becomes apparent that a great star may be known by the distance of her identification.

Viewing Joan Crawford in the 1947 Warner Brothers noir Possessed (with Van Heflin and Geraldine Brooks), which she caught on TV in 1959, Brooks considered that Crawford occupied a less-than-harmonious space between projected image and private person. She regarded Crawford’s performance, as the romantically infatuated nurse Louise Howell, as a magnificent one, but marred by the star’s need to play to audience sympathies:

A better title, Possession — because if Crawford had played her part straight clear through it would have been simply the story of a woman who drives herself mad because the man she wants to possess tosses her off and turns to another girl. But she must have the sympathy of madness — schizophrenia — making her lovable, passive self her REAL self. While her REAL self was the primitive, violent, self-loving creature who only feigned the curbs of society.

Brooks found several scenes “superb,” including those that allowed Crawford to authentically channel darker emotional registers: “The two scenes with G. Brooks in which Crawford treats the girl with uninhibited viciousness (the shooting of Heflin misses because she goes back to sympathy). […] The sneaking evil of Crawford’s close-up waiting for G. Brooks at the top of the stairs is one of the truest and most terrifying faces of a woman ever seen on the screen…”

Strikingly, in her notes on Possessed, Brooks alludes to the star’s great rival, underscoring the dualities of “movie star” and “serious actress” that Crawford and Bette Davis represented in the popular imagination. Brooks opined that Crawford’s performance in Possessed makes “Davis’s evil women pale to the spasms of irritability and hypertension which they were.” Decades later, interviewed for John Kobal’s People Will Talk (1985), Brooks contradicted herself about Davis: “Oh, look, here’s my favorite actress. I liked whatever she did. I think she’s a real actress.”

Reflecting the racially segregated Hollywood in which she worked, Brooks does not seem to have considered actresses of color for Thirteen Women in Films. Yet, the notebooks convey Brooks’s fervent admiration of Lupe Vélez, who worked to evade the confusions of leading a double life, in her stereotypical casting and persona as “the Mexican Spitfire.” Praising Vélez as a “faultless spontaneous actress” in the Columbia musical Honolulu Lu (1941), Brooks loved Vélez’s “charming, grotesque, original movement” as cabaret performer Consuelo Cordoba. Asserting her individuality through her skill at parody, while satirically performing white femininity, Vélez delighted Brooks with her “imitations of Dietrich, Swanson, (and Katharine) Hepburn…”

“We are many and we are one…”

Easy to overlook within the babel of Prime Video, John Lewis’s Silent and Forgotten continues Brooks’s unfinished work. Drawing extensively from the published essays of Brooks’s Lulu in Hollywood, Silent and Forgotten does not allude to Thirteen Women in Films. Yet, the film’s focus and structure strongly suggest that, in another way, it finishes what Brooks started. Silent and Forgotten recalls Thirteen Women both in the number of women featured and in its narrative framework, which evokes Card’s description of Brooks subjectively writing “herself into each of her chapters.”

Written and directed by Lewis, Silent and Forgotten defies easy categorization; it suggests a mix of feminist documentary, film biopic, and theatrical one-woman show. The film self-reflexively layers direct-address monologue, silent film footage, and reenactments of both off-camera interactions and scenes from referenced films. With its giddy formal experimentation, Silent and Forgotten reframes “Great Man” documentary tropes as collective female biography; the film trades linear master narrative for a self-multiplying chorus of female voices, unified by the perceptions of Brooks.

Like a sober classmate of Drunk History, the film leans into its camp instincts and gaudy artifice. The film makes no effort to hide its low budget, such as when performer (and the film’s co-producer) Jacquie Donley, who plays all 13 stars, portrays Pickford with little more than a fright wig that looks assembled out of ramen noodles. If Silent and Forgotten at times embraces the maudlin implications of its title, the film is commendable as an idiosyncratic tribute to Brooks and her peers, a work that reflects both the themes and conceptual novelty of Brooks’s Thirteen Women.

In Silent and Forgotten, Brooks/Donley narrates her flight out of Kansas, which flung her into the Broadway of the Ziegfeld Follies and, then, the Hollywood Dream Factory: Ozian fantasy lands roiled by treacherous sexual politics. Donley, as Brooks, candidly discusses the systemic prevalence of the casting couch: a topic that the actress discussed openly in the 1970s. Brooks’s turn to film history serves as an interweaving framing device, as the actress comments upon the narratives of 12 other women who worked in silent-era Hollywood: Bow, Pickford, Gish, Davies, Dietrich, Pepi Lederer, Lottie Pickford, Virginia Rappe, Olive Thomas, Theda Bara, Colleen Moore, and director Dorothy Arzner, who worked with Bow on The Wild Party.

Silent and Forgotten celebrates actresses who defied producers’ ideas of their “interchangeability,” reflecting Brooks’s intentions for Thirteen Women in Films. A medley of male actors play the film’s impresarios, studio heads, and directors, from B. P. Schulberg to William A. Wellman. By contrast, Silent and Forgotten subverts Hollywood’s history of typecasting actresses as virgins and vamps. Donley plays not only Brooks, but all of the “Silent Stars,” sometimes simultaneously in the same frame. “We are many, and we are one,” Donley, as Brooks intones at the film’s beginning. Yet, Donley being white, silent-era actresses of color, such as Vélez and Anna May Wong, are excluded from the collective, even as revealing their worse experiences in Hollywood would have added further complexity to the film’s argument.

Most prominently, the film narrates the stories of Pickford and Bow, the former as an entrepreneurial trailblazer whose negotiation skills allowed her to spectacularly monetize, if not completely control, her image as “America’s Sweetheart.” With more pathos, Silent and Forgotten dramatizes the story of Bow, raised amid an environment of poverty and abuse in a Brooklyn tenement. As the flapper star, Donley narrates her hypocritical treatment by a movie industry that profited from her “It,” but couldn’t handle her unashamed sexuality or disdain for Hollywood’s high-society pretentions. The film echoes Brooks’s Thirteen Women notes on Bow, whom the former adored in the 1926 comedy Mantrap: “Clara a remorseless little tramp — and empirical triumph.”

As if inspired by Brooks’s critical example, the other Silent Stars begin to comment on each other’s lives and careers. Though opposed in their star personas, Pickford and Bow both move beyond narrating their own stories to eulogizing the legacies of one another. Silent and Forgotten builds upon Brooks’s film criticism to recognize not only actresses’ dualities, but to envision a culture of solidarity within a Hollywood system that so often pits women against each other (a particular “vicious grinding” that Brooks critiqued in her Lulu in Hollywood essay, “Gish and Garbo”). The final scene of the film returns focus to Brooks, now retired and aging, as she quotes a 1972 letter she wrote to her brother Theodore: “For I failed in everything — spelling, arithmetic, riding, swimming, tennis, golf; dancing, singing, acting; wife, mistress, whore, friend. Even cooking. And I do not excuse myself with the usual escape of ‘not trying.’ I tried with all my heart.”

Amid this chronicle of self-criticism, Brooks never mentions writing. If Brooks failed to complete or publish Thirteen Women in Films, this formative work shaped her skills as a historian and critic, roles which she performed with increasing confidence and authority in her essays of the 1960s. Brooks observed: “When you write about something you know, every fact, every word snarls at you till you get it right.” Silent and Forgotten advances conversation about Brooks as a prescient feminist critic, analyst of celebrity, and a complicated woman who fearlessly dismantled the myths around her own star persona, all in the service of knowledge.

¤

LARB Contributor

Maya Cantu teaches on the Drama and Literature faculties at Bennington College. She serves as Dramaturgical Advisor at Off-Broadway’s Mint Theater Company, and as Editor of Book Reviews for New England Theatre Journal. She is the author of American Cinderellas on the Broadway Musical Stage: Imagining the Working Girl from Irene to Gypsy (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

LARB Staff Recommendations

“Lights, Camera-maids, Action!”: Women Behind the Lens in Early Cinema

Gordon and Grimm consider how the camerawoman fought for relevance and visibility in the days of early cinema and ask why we continue to forget her.

The Astonishing and Multiple Achievements of Alice Guy-Blaché

Sarah Gleeson-White reviews a new documentary about a female cinematic pioneer.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!