Cold War Cold Files

A Hungarian author confronts his parents’ Cold War past.

By Ksenya GurshteinOctober 17, 2018

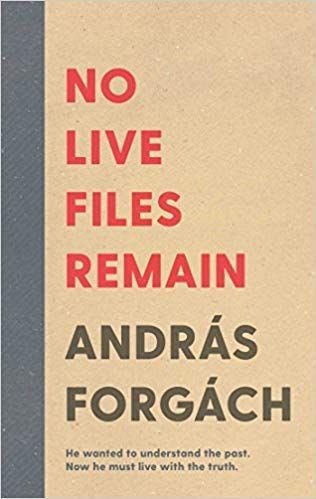

No Live Files Remain by András Forgách. Scribner UK. 400 pages.

AS SOMEONE WHO HAS spent a decade researching and writing about unofficial or semi-official visual art in Eastern Europe during the Cold War, I have come to believe that the American wing of my academic discipline — art history — is deeply disinterested in the place I study. Eastern Europe is too obscure and un-canonical to be of concern to “Western” art historians, and it is too European to count as “non-Western.”

Add to this the inevitable fact that, as the Cold War recedes into the past, it becomes an ever-smaller blip on the radar screen, despite the steady stream of news about the turn toward authoritarianism, chauvinistic nationalism, xenophobia, misogyny, and other manifestations of the politics of scarcity, fear, and hate across many parts of Formerlandia (the former Eastern bloc, former Yugoslavia, former USSR).

In this context, András Forgách’s book No Live Files Remain serves as a valuable reminder of the continued relevance of Eastern European thinkers who have brought great urgency to questions of personal and communal responsibility in the face of difficult historical circumstances. In a time when it might seem tempting to return to polarizing Cold War narratives, the work of writers like Forgách shows that there is much to be gained by searching for similarities between “us” and “them.” His book illuminates the ways in which we are all caught in history, bearing responsibility for how we respond to events.

No Live Files Remain tells of events that intruded suddenly and violently on the lives of the Hungarian writer and his older brother, the filmmaker Péter Forgács. (In 2016, the brothers jointly created a multimedia exhibition at Budapest’s Robert Capa Contemporary Photography Center dedicated to the subject.) In 2014, András learned from an acquaintance working in the secret police archives that both of his parents, Marcell and Bruria Forgács, had for years been “secret colleagues” — i.e., informants for various units within Hungary’s socialist-era Ministry of the Interior. Their code names were Mr. and Mrs. Pápai. This discovery, as might be expected, came as a huge jolt. His mother, Forgách writes, was “a tiny screw […] in the machinery of a petty apparatus. A component that […] couldn’t be more insignificant”; and yet,

how you feel about every moment you spent with this tiny screw or cog […] is changed […] Everything is now suspect, especially beauty […] There is a shadow over all of it, and it can’t be spoken about. Nor can it not be spoken about.

The book is Forgách’s attempt to come to terms with the unspeakable. In Hungary, as elsewhere in the former Eastern bloc, communities have been shaken by revelations like those about Forgách’s parents — most recently, when the philosopher Julia Kristeva was accused of having been an agent of the Bulgarian secret police, a charge she vigorously denies. Karen von Kunes, a senior lecturer in Slavic Studies at Yale, argues in a forthcoming book that a 1950 incident in which the Czech writer Milan Kundera inadvertently reported a political subversive to the authorities deeply influenced all of his novels.

Yet very few people (with some rare exceptions) have talked or written extensively about the experiences of children learning difficult truths about their parents’ pasts under state socialism. This gap points to a larger reluctance in post-communist societies to engage with the complicated ethical legacies of the Cold War era. The fact that his parents are dead puts Forgách in the particularly difficult position of trying to reconcile with the choices of people who can no longer explain themselves. The filmmaker Sarah Polley, in her 2012 documentary Stories We Tell, approached a similar problem by casting and staging “home movies” that would fill the gaps in her own family history. Forgách too decided to embrace the blurriness of the line between family memoir and fiction. With the laconic secret police files — reproduced in full, mostly in the book’s footnotes — as his starting point, he imagines his parents’ double lives in vivid detail, adding to cold facts the contextualization and empathy necessary to make sense of the past.

The result is an unlikely page-turner whose nonlinear narration keeps readers guessing how the protagonists will handle the tempests of 20th-century geopolitics. Over the course of the book, the story of his parents’ activities as informants unfolds against the background of their childhood as Jews in Romania and Jerusalem; their families’ losses in the Holocaust; their courtship as two young communists in British Mandate Palestine; their decision to settle in postwar Hungary; the family’s experiences during the 1956 Uprising; the couple’s stay in London, where his father Marcell was a correspondent for the Hungarian News Agency in the early 1960s; Marcell’s subsequent descent into madness; and the lives of the Forgács children as part of Budapest’s countercultural scene in the 1970s and ’80s. (Of the four children, Péter, András, and Zsuzsa all feature prominently, while the fate of the eldest sister, Vera, is conspicuously shrouded in silence.)

But the emotional heart of the book is Forgách’s enraged, anguished, unanswerable question of how his beloved mother, Bruria, could have done what she did. Toward the end, he formulates his indictment of “[t]he naivety that delivers us to evil” most succinctly:

It just isn’t possible that Bruria never sensed that she was constantly and increasingly crossing borders, not just those of nations but also those of ethical norms […] Her border crossings went on and on, their ripple effect affecting the everyday lives of others; not only of unknown strangers but also of friends and relatives, not always directly perhaps, but they undoubtedly buttressed a corrupt and petty bureaucratic dictatorship that served the interests of the Soviet empire and deprived its citizens of their freedom.

Most of the book is spent unraveling the dense tangle of Bruria’s motives for becoming Mrs. Pápai. The reasons for her decision Forgách reveals to be both political (her vehement anti-Zionism and earnest faith in Soviet-style socialism) and personal — i.e., concern for the well-being of her rebellious children, constant financial struggles, a wish to help family members from abroad visit Hungary, and an even stronger desire to visit her family in Israel, something that would have been impossible without her cooperation with the authorities given the tight restrictions on foreign travel in Warsaw Pact countries. Forgách ultimately explains his mother’s actions by chalking them up to her “unbending, maniacal fundamentalism” when it came to her belief in the goodness of communism and the evil of the Israeli state, whose deplorable treatment of Palestinians she could not forgive. Hence, the authorities of socialist Hungary, the enemies of her enemy, were her friends.

Yet, thanks to the vividness of Forgách’s descriptions of his family history, Bruria’s motives appear to have been constantly shifting, as she made difficult choices in the face of her profound power imbalance vis-à-vis the state apparatus. At times, she appeared to “game” the system in the only way available to her — it was thanks to a lie that she “spoon-fed her comrades,” for instance, that András was able to get a passport as a young man and travel abroad with his mother. At other times, she seems to have been on a one-woman quest for what she understood to be justice. One of her few metaphorical “gold stars” as a spy came from her reporting on a Russian scientist in Israel who aided Soviet Jews in their efforts to emigrate. Though her sons condemn her cooperation with the authorities on principle, Bruria was probably not wrong in thinking that an influx of Soviet Jews into Israel would only make the situation of stateless Palestinians worse. Given such a choice — between complicity with one form of state violence or complacency with another — I personally am not sure which option I would have chosen.

Formally, the book approaches the telling of its story in three different modes, a testament to the author’s ability to offer shifting perspectives on the past. In Part I, the longest and most successful section, an unnamed omniscient narrator takes us through a series of scenes in chronological order. Bruria Forgács is consistently the protagonist, but the narrator offers insight into the thoughts of many other characters, from Interior Ministry “handlers” to András himself, who appears as a peripheral figure in his mother’s story. Part II consists of a group of poems entitled “Marcell and Bruria,” which, whatever their merits in Hungarian, seem to suffer in translation, relying too heavily on off-hand allusions, mostly to Greek mythology, and only occasionally offering descriptions that capture his parents’ experiences vividly. The poems do, however, display a strong sense of fluid movement in time, which facilitates connections with the events discussed in Part I.

Finally, Part III, “Something More,” offers a straightforward narrative of Forgách’s family history from the author’s point of view. This part feels a bit too long and meandering, as Forgách wanders through all the stages of grief without, ultimately, arriving at any resolution. There is only so much railing, after all, that you can do against the dead. As for lessons for the living, two interconnected themes emerged as I reached the end of this family saga: the corrosive effects of pervasive distrust and their close relationship to madness.

In passing, the book identifies several other people who worked for the Hungarian secret police. We learn that “[w]hile Pápai could not have known this, his [only] friend, whom he’d worked with […] in the same newsroom, was writing reports about him, too.” Elsewhere, we are told that the Forgács family’s next-door neighbor had been recruited, as had the legendary filmmaker Gábor Bódy, with whom András worked closely in the 1970s. So had Mátyás Esterházy, a former count and the father of Péter Esterházy, one of Hungary’s most notable 20th-century writers. Forgách praises Peter Esterházy’s as-yet-untranslated novel, Revised Edition (Javított kiadás, 2002), which deals with his father’s role as an informant.

These revelations show only a tiny fraction of Hungarian society’s permeation by state surveillance, but they give an ample sense of the network of mistrust that formed the fabric of the world Forgách conjures. The price of this mistrust was the madness (and/or alcoholism) that seemed to lurk in wait around every corner. Forgách discusses his father’s “nervous breakdowns,” which took place in 1953, 1963, and 1973 and resulted in, among other treatments, electric shock therapy for severe paranoia. Forgách reproduces several of his father’s heart-wrenching written pledges to Bruria in which he vows to become sane: “I will exorcise my fears of persecution as of midnight on 20 June 1975 […] I promise to no longer bother with phantasms and to acquire my knowledge of objective reality from Bruria’s recommendations.”

Needless to say, these memos to self did not produce the desired effect. Marcell — who, according to his son, helped to destroy the Hungarian free press in 1949 and later had to participate in the show trial of his former boss — continued to believe that there was a secret committee tasked with destroying him. “There are no words to describe,” Forgács writes, “a body whose flesh has been gnawed away by fear.”

Perhaps the craziest part of Marcell’s story is that his madness was not an unreasonable response to his experiences as an informant. For how many others was this true as well? This question lends urgency to Forgách’s writing, making it important beyond the confines of his own family. “Let’s learn a new language, a new vocabulary,” he suggests.

[L]et’s get to know more intimately a world that revolts us […] a world that, until now, we’ve observed from such a comfortable distance. Those were always others. Other people it was always so easy to judge […] And, now, here it is, under our skin, worse than a tattoo, because it is invisible. […] [P]art of the tragedy is that it’s not exceptional.

The unexceptional tragedy continues to haunt Forgách, the son of two “network individuals” — a remarkably apt bureaucratic euphemism that points to the fact that pervasive informing bound everyone together, from those who wrote the reports to those who read them to those who appeared in them to those who could never be sure that they did not appear in them. Hence the interwoven tragedies — personal traumas bound up with familial, communal, national, and international ones, all passed down through the generations. And hence the need to speak about the unspeakable and to find a language in which to do so.

In researching this review, I came across an account of people from the former GDR who speak about their experiences of having been agents of the secret police, the notorious Stasi, or having come from families involved with the repressive apparatus. The article quotes Angela Marquardt, a German politician who had been involved with the Stasi as a teen, describing herself as an “affected person.” Though surely imperfect, like all terminology describing moral gray zones, Marquardt’s term captures the reality that, outside the limited scope of the juridical lustration implemented unevenly across Eastern Europe in the decade after the fall of the Berlin Wall, there is never going to be a satisfying, conclusive settling of the historical score, a neat division of everyone into the the righteous and the wicked. Though there is a time and place for designating villains, victims, martyrs, and heroes, it is equally important — for the living more so than the dead — to understand, from a place of compassion rather than judgment, the daily life of their forebears as an interconnected web of affected persons, a web from which later generations can extricate themselves only by speaking out about it, in books such as this one.

¤

LARB Contributor

Ksenya Gurshtein is an art historian, curator, writer, editor, and translator. Her academic research, which focuses on art in postwar Eastern Europe, has been published in ARTMargins, Studies in Eastern European Cinema, Russian Literature, and The Getty Research Journal. Her art criticism can be found online at Hyperallergic and on the Russian arts and culture portal Colta.ru. She lives in a weird place in her head and resides in Los Angeles.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Soviet Pseudoscience: The History of Mind Control

The long, strange history of Soviet mind control experiments.

Goodbye, Eastern Europe!

Jacob Mikanowski shares a few lessons about a vanishing Eastern Europe.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!