Books to Hold and Hold On to: Kaouther Adimi’s “Our Riches”

Abby Walthausen appreciates “Our Riches” by Kaouther Adimi, translated from the French by Chris Andrews.

By Abby WalthausenApril 29, 2020

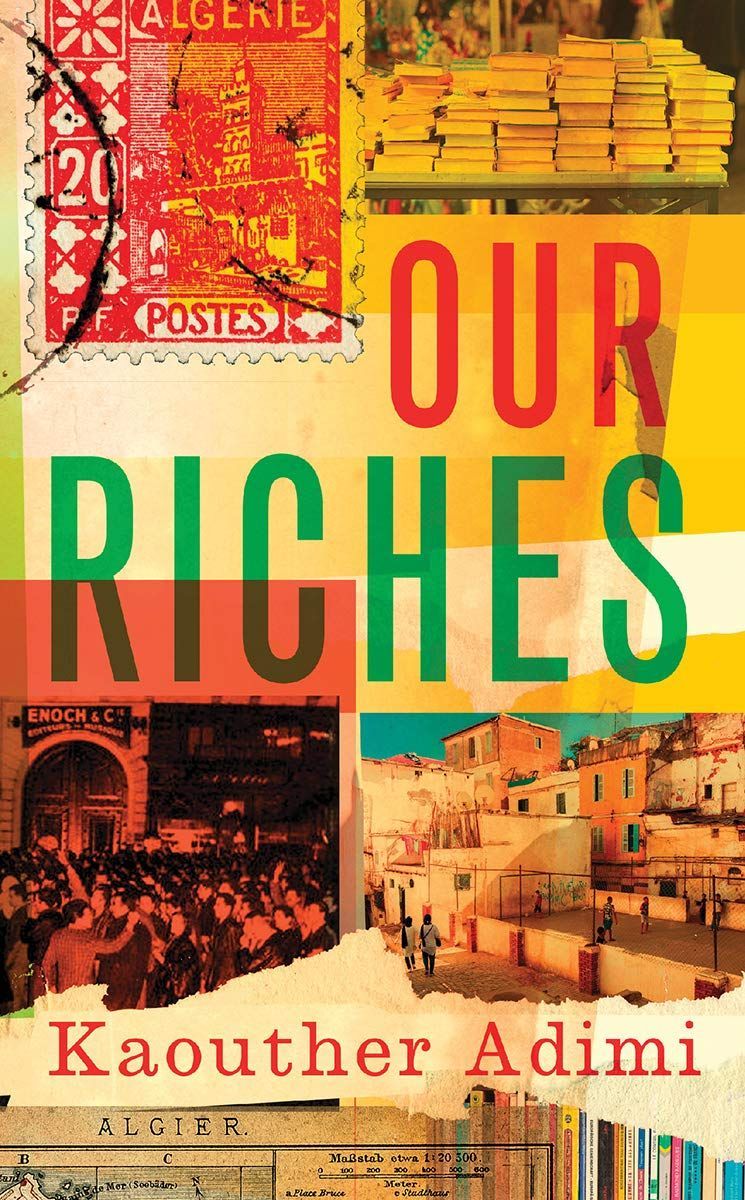

Our Riches by Kaouther Adimi. New Directions. 160 pages.

IN A QUARTET of early essays entitled Nuptials, Camus dwells on the sensuality of the Algerian landscape. Sometimes veering into a racist and imperialist attitude toward the “national culture,” Camus claims that the intellect suffers by the sensual riches of the land. He writes that “the land contains no lessons. […] Everything here can be seen with the naked eye, and is known the very moment it is enjoyed.” The corrective to this, according to Camus, is to find “clear-sighted souls.” But what Camus doesn’t divulge in the essay is that he has already found such like-minded souls stirring up an intellectual scene in Algiers. The essay itself would be one of the writer’s first published pieces, released in pamphlet form by his friend Edmond Charlot.

In Kaouther Adimi’s second novel, Our Riches, recently translated into English by Chris Andrews, the author tells the story of Edmond Charlot’s famed bookstore, Les Vraies Richesses. She juxtaposes two strands of its history — in one she creates a journal kept by Charlot telling about the store-cum-publishing-house-cum-cultural-space from its inception to its near destruction during the Algerian War. In the second strand, she follows a contemporary university grad named Ryad who is hired to clear the bookstore to make room for a beignet shop. Spoiler alert: The books and papers (among them correspondence with Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, André Gide, Jules Roy) are trashed; the place is readied for the beignet shop. It sounds like Camus’s old cynical critique, that the ephemeral pleasures always win in Algeria. That may be where a plot gloss leads, but in this engaging and place-rich book, it is Adimi’s project to marry the sensuality and the intellect that young Camus fretted over, and to show that there are as many ways to be a bibliophile as to be a sensualist.

Adimi does not begin the book with either plot line but instead with a direct address to the reader, leading us through the streets of Algiers, setting the tone for her relationship with the multilayered histories of the city. She harks back to the traditional flâneur of French literature — one who is reflective, and in a nod to Walter Benjamin, one whom she enjoins to ignore the Haussmann-style buildings and instead seeks out the alleyways and the courtyards and the secret stairs. But she sets us down firmly in the present, calling up alongside her flâneur modern-day flaunters, those parents who photograph their children next to old monuments and rush to share them on social media. This voice of the urban guide bookends the work, maintaining the tension between what is to be absorbed carefully, and what is to be consumed quickly.

It is in this wandering that Adimi says she got the idea for the book, that she noticed a store window painted with the words “One who reads is worth two who don’t.” It is an intriguing and reactionary statement, easy to agree with until you realize how it weighs people. It is a snobbishness that Adimi dispenses with immediately.

Abdallah, only semi-literate, has spent many years in charge of the bookstore, which is now an underutilized (five active borrowers only) branch library of the Algiers public library system. He is the “préposé aux prêt,” a bureaucratic if accurate term that Andrews chillingly translates as “loan officer.” The narrator tells us that we call him “bookseller.” He lives with the books, he cares for them, he stamps them and keeps them clean. He taught his daughter to love them and remembers a fond moment of her childhood, watching her absorbed by the books around her. He protects the bookstore from Ryad not through aggression, but by remaining close at hand to demonstrate the value of the books.

Ryad, upon his arrival, has a horror of books. He not only hates to read, but the presence of the books is formidable for him:

All these books are making Ryad anxious. He doesn’t like words bunched together in a line or on a page; they unsettle him. Those black characters printed on white paper remind him of mites. His mother is terrified of mites: she scours the house with bleach from dawn till dusk. Do publishers and printers even think about this? Are they aware of the risks associated with mite infestations? Do they even care? And do readers know what they’re picking up and holding?

Little by little Abdallah, even though he is not a reader, does what he can to present books as magical objects. One night he brings Ryad to a café where a blind man named Youcef can identify and quote from any book just by the feel of its cover. With this sensory skill, he holds court at the café, delighting a table full of attractive young women.

When the neighborhood bands together behind Abdallah to resist the closing of the store, they do not actually spring to the aid of the books. Hardly anyone takes books home, or tries to find new homes for them. Instead, they refuse to sell Ryad paint. It is no way of halting the destruction of the books and papers of Les Vrais Richesses, it is only a way to yoke Ryad with their physicality. In the end, Ryad cannot paint the empty walls of the bookstore with the blue shade of his French girlfriend’s eyes — he must scrub the walls clean until he sweats. Here Adimi forces Ryad to confront the mites he dreaded, as well as the very ink, skin, and matter of the men who’d worked on and read all the books he was disappearing. The books themselves are mostly destroyed in the rain, a far cry from the “desiccated” Algeria of Camus’s consternation. One very important one survives, though — on a whim, Ryad sends The Roundness of Days to his girlfriend. It is a book by Jean Giono, which Charlot printed and gave as an opening gift to his first customers. It is given new context; it comes around again.

In an interview on the French/German culture channel ARTE, Adimi claims that she prefers to call her books “histoires” or “stories” rather than “romans” or “novels.” At the outset of the book too she makes an important distinction between “History with a capital H, which changed this world utterly” and “the small-h history of a man, Edmond Charlot.” Though the book is carefully researched from what remains of Charlot’s papers, the research never feels heavy or academic. Adimi could easily have created a Ryad who was enthusiastic rather than apathetic, a character designed to read and delight in Charlot’s journals. He could have been a proxy for Adimi, a scholar interested in minutiae, and learned to deeply appreciate the history through them. But Admini daringly chooses a Big H approach and uses two non-readers, ones who never pick up the texts of the bookstore’s heyday. The joy and the excitement is lost on them — for Abdallah, the relics are sacred but mostly meaningless, like the Cairo Geniza filled with miscellaneous text but protected fiercely. For Ryad, they are simply a burden.

Still, the journals that Adimi writes in Charlot’s voice are brief and fleeting enough that they read like an oddity rather than a portrait of a literary influencer. Though the period spans Charlot’s entire career, a time during which he married and had children, all the sensual detail centers around book layout, binding, font design, a preference for texture Japanese paper over smooth vellum and so on. The personal life and the life of the body are elided, not in favor of the intellectual life exactly, but in favor of paper. And this choice serves the book well, because although Abdallah, Ryad, and Madame Charlot do not pick up the journals, it feels like they could. Adimi’s Charlot sketches out the lightest side of a love of books. He worries about materials and material shortages, rather than struggling with literature. There is an inclusivity in the way that literature is discussed, one that is much at odds with the snobbery of the window sign.

The tricky thing about books is that they are non-consumable. It is why Ryad’s employers say — especially so near a university — that a beignet store has unlimited possibilities. Even in all their sensuality, whether velvety pristine or grimy, books are not used up by the senses. They may be “for the young,” as a second window sign at the bookstore claims, but they stick around to watch the young age. Reading may be considered a piety that confers worth, but in Adimi’s universe protecting the physical book is selfless, and thus of more noble value than the act of reading itself. In our fascist times, those who honor books even without particularly liking them or reading them are the real heroes. They hold on for posterity, they keep the books for the young even through this era, when so much of the text that surrounds us is quick and ill-considered and without physical presence.

¤

LARB Contributor

Abby Walthausen’s writing has appeared in The Public Domain Review, The Paris Review Daily, The Atlantic, Zocalo Public Square, Atlas Obscura, Common-place, Mutha, Extra Crispy, and LARB. Fictional work has been published by Gigantic, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, the Made in LA anthology, and is forthcoming in Sycamore Review and Santa Monica Review. She lives in Echo Park, where she guides a tour about 20th-century printmaker Paul Landacre, and is at work on a novel, St. Cyr.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Logic of the Rebel: On Simone Weil and Albert Camus

Robert Zaretsky considers Albert Camus’s posthumous friendship with Simone Weil.

Writing Algeria

Kamel Daoud is a brilliant, indeed dazzling, thinker: his sharp turns in thought and language, as well as his subject matter, gave me motion sickness.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!