Beamed from Within: On Harlan Ellison’s “Greatest Hits”

Greg Cwik reviews the new compilation of work from writer Harlan Ellison.

By Greg CwikMay 24, 2024

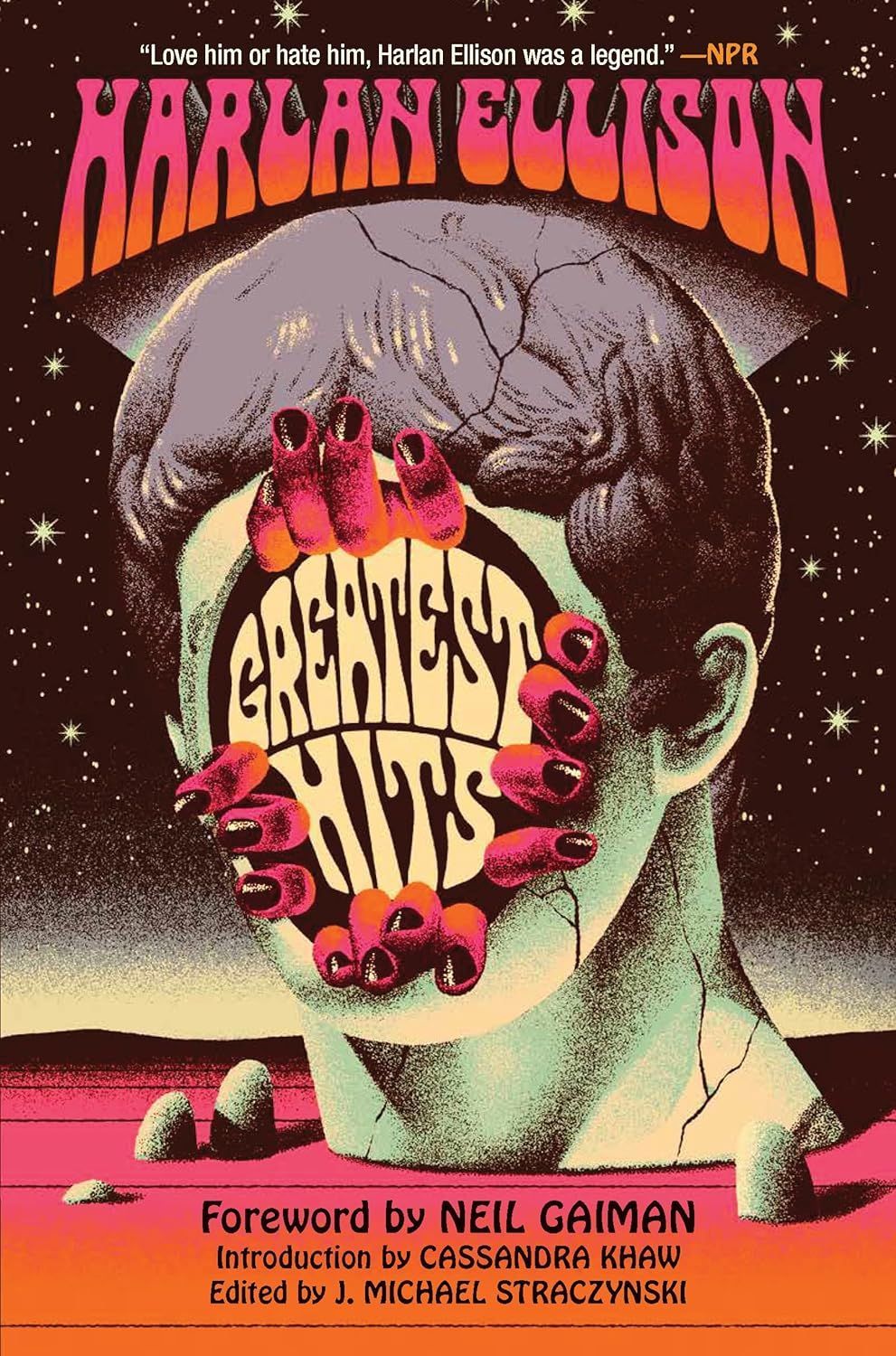

Greatest Hits by Harlan Ellison. Union Square & Co.. 496 pages.

Reality is not always probable, or likely.

—Jorge Luis Borges

CALLING THE GROUCHY and godly Harlan Ellison (1934–2018) a “science fiction writer,” pegging him as a single-genre scribe, is an inaccurate and constraining description. Granted, he wrote a lot of sci-fi, much of which remains redoubtable, replete with indelible, iniquitous, uproarious images conjured by his acerbic abstractions of language and oddball ideas, enigmas left lingering by the last sentence, taunting with its refusal of simple explanation; this is what he will always be known for. But he was just as deft at fantasy, horror, semirealistic (though still deranged) fiction, essays, and cultural criticism, all insightful, erudite, vulgar, angry, hopeful, exact, and exacting. He even dabbled in television, a medium he often disliked, sometimes fervidly, but which proved profoundly successful for him—his revered Star Trek episode, however much it got changed, does everything an episode of television can do.

Ellison, as irascible as an icon can be, is one of the 20th century’s indispensable writers, as larger-than-life as any of his fantastical conjurings, always imbuing his work with the ardor of a lunatic. He is an English-language heir to Jorge Luis Borges, a man who wields words like weapons to assault reality, to provoke us through discomfort. Tenacious in both terror and tomfoolery, fierce, and funny, Ellison wrote with ardor and a howling soul.

Herald Classics’ Greatest Hits (2024) assembles Ellison’s most popular, award-bedecked stories, science fiction or sci-fi adjacent all, mostly from his middle and early-late career, when he was at the apogee of his powers. Selections include “The Deathbird,” “The Whimper of Whipped Dogs,” “Shatterday,” “The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World” (God, he was good with titles), and other winners of Nebulas, Hugos, and Locuses. Given the fact that many of his best books are out of print and the behemoth The Essential Ellison (1987) costs a fortune, this book, while hyperfocused on his sci-fi output, is both an excellent introduction to the man for neophytes and a convenient volume for acolytes. It is a comfort in those times when you really just need to read about the Ticktockman and his Kafkaesque nightmarishness, or the tragic entrapment of lonely souls in an artificial world, cyber-Beckett, or a derelict gothic bastion of Poe’s dread fictions for the post-nuke age. Ellison’s lesser stories—or, rather, less-read stories—are tragically absent by nature of the collection’s goal, but everything that we do get is gold.

In 1996, the year he won a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Horror Writers Association, Ellison defined his writing for us: “What I write is hyperactive magic realism. I take the received world and I reflect it back through the lens of fantasy, turned slightly so you get a different portrait.” Ellison wrote like a man suffering from perpetual fever hallucinations, his stories governed by an inimitable eerie logic. I don’t want to spoil them for any newcomers, so let’s forgo the plot synopses—which are pretty hard to write anyway—and consider instead the writing. There’s an art-rock musicality to the syntax and rhythm that anticipates the elegiac and energetic lyricism and technological tinkerings of Iggy Pop and David Bowie’s The Idiot (1977), and Bowie and Brian Eno’s Berlin Trilogy (1977–79). “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream” is both the bastard progeny of Alfred Bester and Robert A. Heinlein and the forebear of William Gibson, whose Sprawl trilogy (1984–88) culls from Ellison’s postmodern brain-melter (in “‘Repent, Harlequin,’ Said the Ticktockman,” Ellison refers to the “communications web”), a work of existential oneira. Look at the rhythm, the strangeness:

I am a great soft jelly thing. Smoothly rounded, with no mouth, with pulsing white holes filled by fog where my eyes used to be. Rubbery appendages that were once my arms; bulks rounding down into legless humps of soft, slippery matter. I leave a moist trail when I move. Blotches of diseased, evil gray come and go on my surface, as though light is being beamed from within.

Outwardly: dumbly, I shamble about, a thing that could never have been known as human, a thing whose shape is so alien a travesty that humanity becomes more obscene for the vague resemblance.

Inwardly: alone.

Gray, a color, is written about as if alive, diseased and evil, a thing that is somehow subhuman. In “The Deathbird,” Ellison describes rocks in a “magma pool”: “White-hot with the bubbling ferocity of the molten nickel-iron core, the pool spat and shuddered, yet did not pit or char or smoke or damage in the slightest, the smooth and reflective surfaces of the strange crypt.” Notice how he imbues an ostensibly natural occurrence with the qualities of a living thing, bitter and destructive yet inexplicably unable to damage the slick, shiny surface—personifications Ellison often employs in his descriptions of technology. Notice his use of negatives to create a clearer image by restraining the possibilities of your imagination yet lighting a spark of curiosity: we have no idea what the crypt is, but it is seemingly impermeable, even by magma, and we must find out why. In “The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World,” the first sentence is a slippery but coherent account of wry efficiency detailing how a man, a name to us only, poisons and kills 200 people by corrupting their milk with insecticide. We learn about the man in subsequent paragraphs. “I’m Looking for Kadak,” one of only three stories not adorned with an award nomination, is a rambling soliloquy recalling a strange conversation between strange people, a debate really, peppered with italicized words, foreign and fabricated. There’s an eclectic array of subjects and styles here, yet it always remains unimpeachably Ellison.

Ellison’s writing has the electric shock of a malfunctioning machine, words like sparks spraying out. Yet there is humanity—bitter, yes, and often mean, with lust for life unrequited by the vicissitudes of fate, but Ellison’s best work is endowed with the spirit of man with a big, bruised, beating heart. He was a man fascinated by and disappointed with the society roiling around him, and thus his characters are also often denied penance and peace. Ellison is that rare beast, a writer who suffuses his work with smart-man musings without the boring, masturbatory listing of dead philosophers to boost intellectual credit. Except when he did do that (I’m not judging—I’m doing the same thing). In his nonfiction, he bemoans, with avidity, elitists’ tendency to intellectualize everything, while doing so himself, which he undoubtedly knows, just another layer of irony in the madman’s spiritual coils. He was a complicated, even hypocritical man of singular style and insoluble beliefs. (He also dressed real snazzy.)

Unsurprisingly, you find the blood of the famous existentialists coursing through the veins of his fiction and criticism, a postmodern augmentation of cynical scenarios and maniacal pontifications, hues of the standard brainiacs Roland Barthes and Walter Benjamin with (thankfully) few name-drops. He approached sci-fi like J. G. Ballard, a thinking man’s genre writer who finds in quotidian life horrors too horrible to articulate, except through the lens of the fantastical; Ballard found the humor in horror, the ridiculousness of human progress. Georges Bataille is another of Ellison’s kin, particularly Story of the Eye (1928), if not in the overt salaciousness, then undoubtedly in their shared, unrepentant affinity for perversion as a way of understanding—perversion as methodology.

Ellison was too confident, too egotistical, to resort to the thoughts of others. In his work, you find variations of the Übermensch as technology, and in his personality, you see the Übermensch (see: punching Charles Platt, then boasting of it years later). And yet he fought censorship and advocated for many progressive causes—a man of contradictions. He writes of lost souls purveying their fucked-up worlds in a desperate search for meaning, which they are denied, as are we. As Robert Burton says in his seminal and timeless 17th-century tome The Anatomy of Melancholy, “[H]e that increaseth wisdom, increaseth sorrow.” For Ellison, it is anger that increaseth, an acerbic anger.

Ellison’s interest in the machineries and machinations of systems is of a kindred spirit with the major American postmodernists, and their slang and juvenilia bombinate on every page of Greatest Hits. His sardonic humor and linguistic dexterity are always in service of deeper, darker thoughts, using genre as a vessel for ineffable, uncomfortable, uproarious ideas. Before Nick Land went insane on prodigious amounts of speed, he mentioned the “mystical delirium of [the] atheism” of the Marquis de Sade, and something similar could be used to describe Ellison: the spiritual and secular ruminations of a man torn between modernity and the epochal, a taste for the tasteless and the profundities lurking in it.

All throughout his career, Ellison’s love of (or perhaps obsession with) film manifests in imagery and language, as when he evokes Luis Buñuel’s eternal image of a razor slicing an eye, or mentions watching Marx Brothers movies on tape. In this regard, he again flashes postmodern urges redolent of Robert Coover, particularly Coover’s A Night at the Movies, or, You Must Remember This (1987). Ellison’s images are sharp, yet artfully obfuscated by precise, unexpected language. He fits words together like the many gears comprising Fritz Lang’s chthonic Babylon, paragraphs stacked like the looming metal-and-glass erections scratching the sky, carefully crafted and calibrated apparatuses manufacturing great glinting mysteries never meant to be solved.

And yet, Ellison had a labile, even incoherent relationship with moving images. In Strange Wine (1978), he opines,

I now believe that television itself, the medium of sitting in front of a magic box that pulses images at us endlessly, the act of watching TV, per se, is mind crushing. It is soul deadening, dehumanizing, soporific in a poisonous way, ultimately brutalizing. It is, simply put so you cannot mistake my meaning, a bad thing.

Abhorrer of the boob tube, yet enamored of the big screen, he also, for some reason, voiced an animated character modeled after himself on Scooby-Doo! Mystery Incorporated (2010–13).

Ellison’s film criticism is a strange Pauline Kael–ish style of amateur analysis, imbued with intense erudition and vulgar intellect, undeterrable in its honesty. His writing on movies captures his mercurial essence just as lucidly as his science fiction stories, constituting one of the great bodies of work in pop culture criticism, fiercely intelligent and vehement in love and hate, chockablock with the lucubrations of a stark-raving genius. Ellison’s evisceration of Star Wars (1977) operates at Renata Adler levels of gleeful vociferousness—it is astute and, even if deranged, utterly compelling. Meanwhile, his enthusiasm for auteurs who made films of moral murkiness, like John Frankenheimer and William Friedkin, vibrates with life.

Harlan Ellison wrote stories about modern society, stories with timeless ideas written in a new exciting way, perverse and prescient. He saw the present and wrote of the future. His work is stylishly sui generis, yet in communication with the forebears who have, throughout literature, used the fantastical to understand reality. Ellison’s work thrums with anxiety, and, in sharing these moments, in being unsettled or laughing at our being unsettled, we might feel better—for a while. There’s always a new anxiety looming.

Greatest Hits offers a reason for readers to rejoice, for it is a handy compilation of excellent and eclectic and eccentric stories. At the same time, the book is an example of the limitations of single-volume collections, particularly of writers whose output far exceeds the capabilities of paperbacks. The subjective selection reflects the editors’ tastes and their understanding of what makes a writer unique. As an affordable assemblage of great and popular stories, it rocks; unfortunately, by emphasizing only Ellison’s award-winning sci-fi works, the editors doomed many great gems to obscurity. Some of his best work includes the insane rantings of his exuberant nonfiction, which also sheds light on his more famous fiction.

One of my favorite left-out pieces, on the gleefully grotesque villains of pulp fiction, tells you so much about Ellison (no one would be shocked to learn that he has a fondness for baddies and brutality) and about pulp. But to read that one, you’ll have to track down The Black Lizard Big Book of Pulps (2007), a bulging, beautiful assemblage of gumshoes and dames (see: Ellison’s diverse fascinations?). Meanwhile, Deathbird Stories (1975), some of which is included in Greatest Hits, is an awesome array of insane tales about deities and sublime entities, as much magical realism as it is sci-fi. Still, science fiction will continue to be what Ellison is known for, not unjustly, and you won’t find a better collection of single-scribe sci-fi on the planet—or beyond it.

LARB Contributor

Greg Cwik has written for Reverse Shot, MUBI Notebook, Slant, The Brooklyn Rail, Vulture, and elsewhere.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Red Shredding: On Netflix’s “3 Body Problem”

Christopher T. Fan reviews Netflix’s new show “3 Body Problem.”

What Does “Stylist” Even Mean? On Steven Millhauser’s “Disruptions”

Josh Cook reviews Steven Millhauser’s new story collection “Disruptions.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!