An Irresponsible Obsession: Tara Isabella Burton’s “Social Creature”

Lauren Sarazen reviews Tara Isabella Burton's Patricia Highsmith–esque novel, "Social Creature."

By Lauren SarazenJune 14, 2018

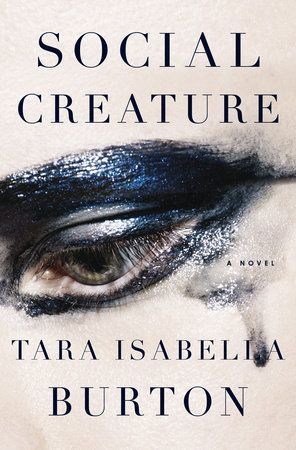

Social Creature by Tara Isabella Burton. Doubleday. 288 pages.

WITH SOCIAL CREATURE, Tara Isabella Burton presents a decadent portrait of wealthy, young New Yorkers and the lengths one might go to become one of them. Louise scrapes by in New York City juggling her barista gig, remote work for GlaZam, and SAT tutoring. At 29, the once-hopeful writer spends her scant spare time compulsively scrolling through clickbait rather than writing. Lavinia, on sabbatical from Yale, spends her days and nights chasing an idealized existence. The unlikely pair meet when Lavinia, desperate for a babysitter for her little sister, calls Louise for SAT tutoring. The agreed-upon three hours stretch until 6:00 a.m. as Louise waits for Lavinia to return and pay her.

When Louise offers to repair the torn hem of Lavinia’s feathered dress, these two disparate young women quickly accelerate into an increasingly toxic friendship. Drawn into nights of exclusive parties and expensive cocktail bars bankrolled by Lavinia, while cozying up to the city’s elite literary scene in borrowed clothes, Louise sees Lavinia’s finances and friendship open doors for her that had been firmly shut. But from the start, we know how Social Creature is going to end — the passionate, idealistic Lavinia will become the Dickie Greenleaf to Louise’s Tom Ripley, and it works.

Despite treading similar ground as Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley in its meditations on obsession and wealth, Social Creature remains distinct through its explicitly millennial perspective. Burton’s use of a close third-person narrative voice complements this perfectly, giving the story a healthy dose of dramatic irony as the characters continuously construct a parallel narrative online via their social media channels. Similarly, the choice to write in the present tense creates a compelling momentum as Louise’s role as best friend shifts following Lavinia’s abrupt demise.

Ironically, Lavinia is consumed by a fierce need to live. It’s a refrain throughout the novel, from captioning her photos “ah! je veux vivre!” to her New Year’s Resolution to “drink life to the lees.” Lavinia is no basic heiress. Prancing in fountains in vintage gowns, she likens herself to a millennial Anita Ekberg. Her photos are captioned with fragments of Edna St. Vincent Millay’s poetry and her casual speech is peppered with lines from Macbeth. Fueled by a quest for poetic exhilaration, her antics are impractical, sometimes illegal, yet free of consequence. Breaking into the High Line after midnight, “[t]hey drink and Lavinia tells Louise about all the places they will go together, when they finish their stories, when they are both great writers — both of them — to Paris and to Rome and to Trieste, where James Joyce used to live, to Vienna to see the paintings, to Carnevale.” Lavinia longs for an extraordinary life, but are her dreams truly unique or simply a recycled narrative? She values Truth, Beauty, Art, Virtue. She bemoans the lack of true talent among her friends, longing for “nineteenth-century Paris” or somewhere with “people who were above all this horrible, pretentious” pseudo-intellectualism. Yet when Louise mentions that someone from the party had said almost the same thing, Lavinia’s self-perception as a transcendental aesthete is cracked.

In this sense, Social Creature perfectly captures the danger and inner workings of curating an idealized identity online. Running parallel to reality, social media’s structure expects users to provide constant check-ins, stories, statuses, photos, and event RSVPs, and Burton’s characters all play along. Their choice to mass-blast their lives online is undeniably relatable. I spend too much time on the internet, and chances are, you do too; there’s a reason apps exist solely for the purpose of curbing time wasted scrolling. Yet, this acquired taste for sharing has transformed narcissism into a social norm. In fact, we might not even see our carefully curated social media feeds as narcissism — we’re just sharing our opinion, or a photo or two. We have to document the moment. It was “one of those nights,” after all. In Lavinia’s case, social media props up her (often ridiculous) absolute commitment to her ideals through likes, and the overwhelming approval of her peer group arguably encourages her to continue on her path. Alarmingly, consistent social media activity is cast as equivalent to in-person interaction, making it possible for Lavinia’s death to slip by unnoticed; everyone is too busy liking her status to really think critically about her glaring absence.

Burton even translates the meticulous detail of a curated Instagram post through her vivid and precise descriptions. Details that might have been insignificant — the hazelnut-cinnamon-pear-cardamom tea they brew in an Uzbekistan teapot, the exact hue of Lavinia’s wine-dark lipstick, or Sehnsucht, and her custom-made perfume mingling lavender, tobacco, fig, and pear — become paramount. Similarly, she artfully sets her scenes. Tapping into Instagram aesthetics, pivotal points of the novel take place in visually stimulating locations: they burn a handkerchief belonging to Lavinia’s ex on the snowy High Line at night, they sacrifice a ruined dress to the sea with the Cyclone looming behind them, and primp for nights out in Lavinia’s apartment with its antique fans pinned like butterflies against the royal blue walls.

Likewise, the novel’s attention to the rules that govern social media is precise. Lavinia’s sparkling social calendar is well documented, thanks to Facebook. Alternating sips from a flask on the frozen Coney Island boardwalk in the wee hours of January 1, “they take a selfie of their naked bodies, from the lips down. They use their arms to cover their nipples, because otherwise Instagram will censor it.” At Bemelmans, they snap a selfie on Lavinia’s phone, and she sends it to Louise to post. “Tag me,” she says. “And make it public, okay?”

One of Social Creature’s overwhelming strengths is just how well it chronicles this obsession. The reader is completely leaning in, and, while this reaction is a mark of a compelling narrative, within this particular world, our engrossed fascination is part of the problem. Throughout the novel, affluence is seen as the tipping point between being in and being locked out. Louise gains entry to New York’s literary world through Lavinia. And sure, Lavinia is distinct: she loves vintage and captions her photos in French and Latin; she lost her virginity to Liszt’s Liebestraum No. 3; and she enthusiastically performs her identity. She’s the type of girl who haunts the site of her first date, “[insists] they go all the time, in Lavinia’s opera cloaks, in Lavinia’s furs.” But would Lavinia be Lavinia without the money? Arguably, it’s her wealth that opens the door to cultivating her lavish eccentricities and brings her membership and clout within her intellectually poised group. At 23, Lavinia is sheltered by a seemingly endless pool of passive income (her bank balance reads $103,462.46 the first time Louise is sent to withdraw cash for her) and she lives rent-free in a lavish Upper East Side apartment that her parents own. Her complete disregard for Louise’s commitments to her jobs — and more poignantly, her lack of comprehension as to their necessary function for Louise’s survival — reveals just how oblivious she is to how people function in the real world.

In the aftermath of her first night as Lavinia’s friend, Louise realizes she’s trashed her borrowed dress, the dress that Lavinia considered a symbol of “beauty and truth and everything good in the world and maybe, even, the existence of God, is in shreds. There are wine stains. There are cigarette holes.” But Lavinia finds Louise’s genuine apology baffling. “We can always get another dress,” she shrugs. For Lavinia, there is always another dress.

While there is romance threaded through Social Creature, the central relationship at its heart isn’t a story of boy meets girl. Instead, Burton explores the darkness within female friendship. I used to think that some desperate thirst for male approval that was behind the insecurities that fractured young women, but after surviving catty high school girl groups, I’m persuaded to say it’s more likely to be toxic female friendships. A cursory glance at beloved narratives will tell you that we idealize female best friends: Cher and Dionne, Thelma and Louise, the real-life duo of Amy Poehler and Tina Fey. It’s you and me against the world, girlfriend. It’s a story we like.

But Social Creature is not that kind of story. Instead, Burton focuses on a different kind of friendship, the kind that builds in intensity until it becomes destructive. Louise discovers Lavinia’s friendships follow a careful pattern: an all-encompassing closeness that manipulates a fear of rejection to exert absolute control for about six months or so, then she discards them. When her demands on Louise’s time result in losing all three of her jobs, Lavinia seems to take pleasure in manipulating Louise’s dependence to get her own way. Yet Louise is unable to emotionally distance herself; her desperation is paired with adoration. Burton hints at this destructive dynamic almost at once. Mimi, Lavinia’s old best friend, mistakes Louise for Lavinia, kissing her neck, murmuring into her ear. After barely a minute with Mimi, Louise realizes that the “strange, pantomime way Mimi is talking” is designed to replicate Lavinia’s distinct speech. Both Mimi and Louise admire her with a ferocity that crosses the line of normal friendship. She becomes a point of comparison, revealing deep-seated feelings of insecurity and inadequacy. Lavinia is that friend — the effortlessly gorgeous one whose idea of a good time is an impossible cocktail of high-stakes risk and serendipity. She “made you feel so special. Until she didn’t […] [but] as long as you played the game…”

While Social Creature seems just too glamorous and magnetic to be true, New York magazine recently ran a piece concerning a fake German heiress. Anna Delvey, a social-climbing con artist, scammed her way through New York, defrauding both banks and her friend out of a collective $275,000. Though Burton confirmed that she wrote Social Creature before becoming aware of the story, the similarities hammer home the mirror it lifts toward our irresponsible obsession with status and effortless living.

¤

LARB Contributor

Lauren Sarazen is a freelance writer who lives in Paris, France. She graduated with a BFA in Creative Writing from Chapman University and received her MA in Literature from Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, where she is currently working toward her doctorate. Her words have appeared in The Washington Post, Vice, Elle, and Air Mail among others.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Aimee Molloy’s Maternal Horror

The gripping horror of Aimee Molloy’s “The Perfect Mother” lies in showing us the demons of motherhood in broad daylight.

Flung Out of Space: “Carol,” Genre, and Gender

"Carol" is unique among Haynes’s films in that it invites us to witness an intimacy that others have failed to notice.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!