An Interview With Myself, After Reading This Book: “Black Rock White City” by A. S. Patrić

Ben Paynter reviews A. S. Patrić's "Black Rock White City."

By Ben PaynterSeptember 28, 2017

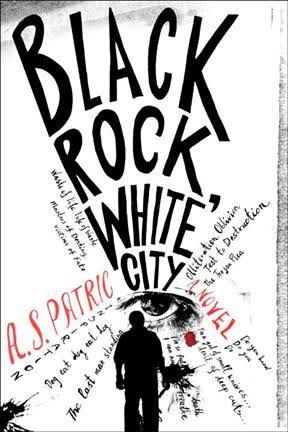

Black Rock White City by A. S. Patrić. Melville House. 240 pages.

I: THANKS FOR TALKING to the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Me: No problem. It’s a wonderful journal.

I: So, tell us a little about the latest book that you’ve read.

Me: Well, I’ve had the pleasure to read the debut novel of the Serbian-Australian author A. S. Patrić. It’s entitled Black Rock White City. It tells the story of an immigrant Serbian couple, Jovan and Suzana, who have set up home in Melbourne after fleeing the horrors of the war that raged in the Balkans throughout the 1990s. They’re both traumatized, but we only find out more about this further into the book. To begin with, the focus of the story is on a series of strange and disturbing acts of vandalism in the hospital where Jovan works as a janitor. Since it’s his job to clean them up, he becomes intimately acquainted with the details of the crime, and with the questions provoked by them. The criminal can only be a hospital employee; but who exactly? Any of the people who Jovan knows personally? And what is the motivation for these precisely calculated, cruel acts? As the reader progresses through the book, these immediate questions begin to overlap with the story of Jovan’s and Suzana’s personal sufferings. The cumulative effect is one of an examination of human cruelties, and the various labors involved in overcoming them.

I: Interesting. Can you elaborate a little on those “acts of vandalism”?

Me: Sure. For example, Chapter One begins with a description of vandalism done to some medical X-ray panels: the phrase “The Trojan Flea” inscribed over the images of three car-crushed skulls. As I’ve mentioned, it’s often Jovan’s job to fix or dispose of the damaged items. Shortly afterward, he’s engaged in removing graffiti reading, “I am so full of your death I can now only breathe your rot,” which has been written in a stairwell. Before long, it gets either more affronting, more revolting, or more incredible: the word “INSPIRATION” carved “from throat to navel” into a cadaver; “DOG EAT DOG” stenciled into canteen crockery; the water in a drinks dispenser replaced with unguent human fat; it goes on. As the novel progresses, the attacks become more targeted against particular individuals, having worse consequences. Although Jovan isn’t always directly involved in the matter — for instance, the human fat must be removed by an expert in a hazmat suit — he easily keeps abreast of developments through workplace rumor.

I: So what relation do these bear to him, other than his mundane obligation to clean up afterward?

Me: Good question.

I: Thanks.

Me: Well, probably merely for narrative purposes, the impression is given that Jovan is the person with the closest, most intimate relation to these crimes, other than the criminal themselves (who comes to be dubbed “Graffito”). The other hospital workers, excluding those directly targeted, are shown as intrigued and appalled yet largely standoffish. It’s Jovan who seems to wage the real, subtle battle against the perpetrator. This, in fact, is a crucial aspect of his character portrayal: the stoic-faced, physically imposing man laboring quietly yet unceasingly to eradicate these wrongs. The more we understand about his psychological makeup, the more we appreciate the mental duress he comes under when faced with such things.

I: You’ve hinted at the complexities beneath the surface of this protagonist. Can you elaborate a little?

Me: Yes. As mentioned, he’s described as being fairly expressionless or plain in the performance of his duties: “His thoughts never register on his face. Looking at him you would think there’s nothing more to him than the effort to dislodge ink from a concrete wall.” His difficulties with the adopted nation’s English language mean that “many of the hospital’s employees speak to Jovan as though his slow, thick words are a result of brain damage.” Compounding this somewhat Neanderthal impression is his bulky physique: “six-foot-four and broad, thick boned with hands that can wrap halfway around a basketball.” Patrić shows considerable accomplishment in balancing this version of Jovan — the humbled immigrant laborer, subject to prejudice and stereotyping from other Australians — with the version that his close associates know. Early in the story it’s related that Jovan was in fact a published poet in his past life, as well as a lecturer in Yugoslavian literature at the University of Belgrade. His wife had also held an academic position. The narrative of the novel is punctuated with italicized phrases of what can only be poetry occurring spontaneously to the protagonist, as in: “Clean, virginal snow, a disguise for the Blue Sky, in love with its floating White Angels, draped over the everything below of Shambling Feet, burying all in the heavy Broken Beneath.” These provide an insight into the — to resort to cliché — sensitive poetic soul of the man whose daily labors might otherwise belie it. Furthermore, since in the whole book Suzana seems to be the only person who knows him profoundly, this poetic aspect serves as an access for understanding the deeper zones of their relationship.

I: We’ve heard mostly about him; what about her? And what is the significance of their partnership?

Me: Jovan does, indeed, stand center-stage for much of the novel; indeed, this could be seen as a shortcoming of plot, but I’ll come to that. For one thing, he’s the agent of interaction with the hospital and its theme of mysterious cruelty in the form of “Graffito.” His affair with a dentist is also described in some detail, a scenario that seems justified mainly in its juxtaposition of a brutally simple and purely sexual relationship alongside one which is damaged and infinitely more complicated yet ultimately of vital importance.

Suzana undoubtedly occupies the passenger seat in this fictional vehicle, although she progresses gradually to greater prominence until almost occupying center-stage herself. One regard in which this plays out is the transfer of attention (intended or not, I cannot say) from Jovan’s poetry to her newly forming novel. This is not incidental, but relates to a major trope of the book overall, which is the issue of whether words can at all retain their beauty and soulfulness in the aftermath of catastrophe; what their meaning is to the traumatized. One of the first descriptions of Suzana relates how she prefers to leave post-it-notes around the house rather than communicate with Jovan directly. Their dialogue is always tortured and troubled, and their conversations depicted so: “No dinner banter. Wordless meals. Afterwards they talked about the lovely weather, as though they were strangers with little in common.” Jovan himself remarks to another character: “I never taught you how useless words are, did I?” Even the scriptural nature of Graffito’s vandalism bears on the issue. This strikes me as unsurprising from a writer who works as a bookseller. Whereas her husband seems to have all but abandoned his actual intention to write, Suzana is making huge efforts to express herself again. These efforts, and their results, represent one victory over the depression of exile and alienation. The process affords her some degree of reconnection with her cultural and social history, not to mention with herself and, in time, her husband.

Whilst trying to avoid spoilers, it has to be mentioned that both Jovan and Suzana were the victims of atrocities perpetrated during the war, incidents that have made their partnership almost impossible to endure; yet that even these sufferings are overshadowed by the loss of their children in the same period. It’s the latter in particular that goes some way to explain their curious state of limbo or aphasia within the fairly meaningless outer sphere of Melbourne: his stoic dealings with Graffito, her cleaning and caring for clients in wealthy suburbs, their routine silence and distance. The novel handles these immensely delicate issues with an intriguing deftness, examining their different aspects, so that at one moment it seems like the couple will surely sunder apart and at another moment like the grief is precisely what keeps them together.

Patrić does succeed in creating an interesting and distinct character in Suzana. Her relationship with her friend Jelka, solidly supportive yet witheringly critical, and practically bawdy in language, feels authentic. Her depression is conveyed convincingly, and the author shows care in his treatment of her femininity. Still, I can’t avoid the suspicion that her character suffers the flaw of being a mind-and-body counterbalance to the main role of the male. Jovan is a doer — in spite of his poetic interludes, we witness or experience him foremost in action, whether it be mopping blood off floors or making love to his mistress, discussing the crimes with colleagues or fixing his van. His engagement with the past is limited to a kind of persistent, low mental aching that only the narrator can hold up to the light. Suzana, by contrast, acquires little physicality across the pages and exists more as an emotional entity, disturbing the fabric of Jovan’s life outside the hospital, and retreating alone to mourn. An example of the disparity is that Jovan’s psychological strife is packaged as an ineffable descending “blackness” that we can only really witness from the outside, whereas Suzana’s inner conflicts are relayed more directly. Does this partly reflect a culture where men are traditionally expected to be more resilient? The final scene of the book seems to exacerbate this issue, and will doubtless leave some readers wondering whether the couple’s relationship isn’t a little too narrowly defined. I’d be interested to know what female readers think of the character of Suzana.

I: Okay. And the significance of “Graffito” in all this?

Me: Graffito seems ultimately to be some kind of meta-plot, inasmuch as his crimes could be interpreted as representing the crisis of language and the sublime against cruelty and mortality that afflict the protagonist’s mind; however, since this isn’t much hinted at, it could equally be described as merely coincidental horror that triggers certain traumas. If the latter, it’s also open to accusations of being a trick to lure readers in; though it’s hard to see why that would be necessary, given the book’s topic of war. Perhaps violence in the sterile hospital is needed to demonstrate that the evils that cause refugees to flee in the first place are, in fact, lurking and haunting them everywhere, rather than being confined to a theater of conflict. Nevertheless, the point of the whole Graffito plot line doesn’t seem to be sufficiently resolved, from my perspective.

I: Does the book do justice to the conflict? Is it a war book? An émigré book? An Australian story? To whom does it appeal?

Me: In this sense, Patrić has certainly accomplished something notable. His book manages to do all those things, considerately, at once. It does justice to the conflict in its precise, harrowing historical recollections, and simultaneously in its refusal to get drawn into vulgar drama. In its distancing, then, it’s resolutely not a war book and is a book about refugees and their trauma. (This stands to reason, since the author himself is a Serbian émigré to Australia, and likely has close personal relations to the conflict.) Whether or not it’s an Australian book is possibly irrelevant, possibly problematic. Either way, both the Australian landscapes and inhabitants come across as somewhat wooden supports to the central personal dynamic. The city is barely described, the land itself loosely, and most attention given to the ocean. The people, similarly, tend to be annoyingly empty — as much to the reader as to Jovan and Suzana. Could this be the symptom of a profound sense of alienation from the adopted culture? Is it just that it wasn’t necessary to go into such details? Personally, I would have preferred a richer appreciation of peoples and place.

I: So. The big moment. Good read or not?

Me: This is a good read, no question. As a debut novel, I’m pretty sure — or at least hope — that this marks the emergence of a force to be reckoned with in Australian literature. I enjoyed the writing, and was kept going along nicely by the plot, which might have been smartly edited.

I: Bags of popcorn, soda cans?

Me: I’d have to give this book three out of five popcorn bags, and maybe four out of five soda cans for its depiction of the central relationship.

I: Thanks!

Me: My pleasure. LARB is such a high-quality journal.

(Interviewed August 14.)

¤

LARB Contributor

Ben Paynter is a journalist, editor, and writer with a background in book-selling. He holds degrees in Literature, Philosophy, and Creative Writing from the universities of East Anglia and Manchester, in the UK. He currently resides in south Germany.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Land Down Under

Jean Hey reviews David Francis’s novel "Wedding Bush Road."

War and Girlhood

“The war in Zagreb began over a pack of cigarettes.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!