All the World’s a Stage: On Yukio Mishima’s “Star”

Jan Wilm reviews Yukio Mishima's "Star," recently released by New Directions in a translation by Sam Bett.

By Jan WilmJune 18, 2019

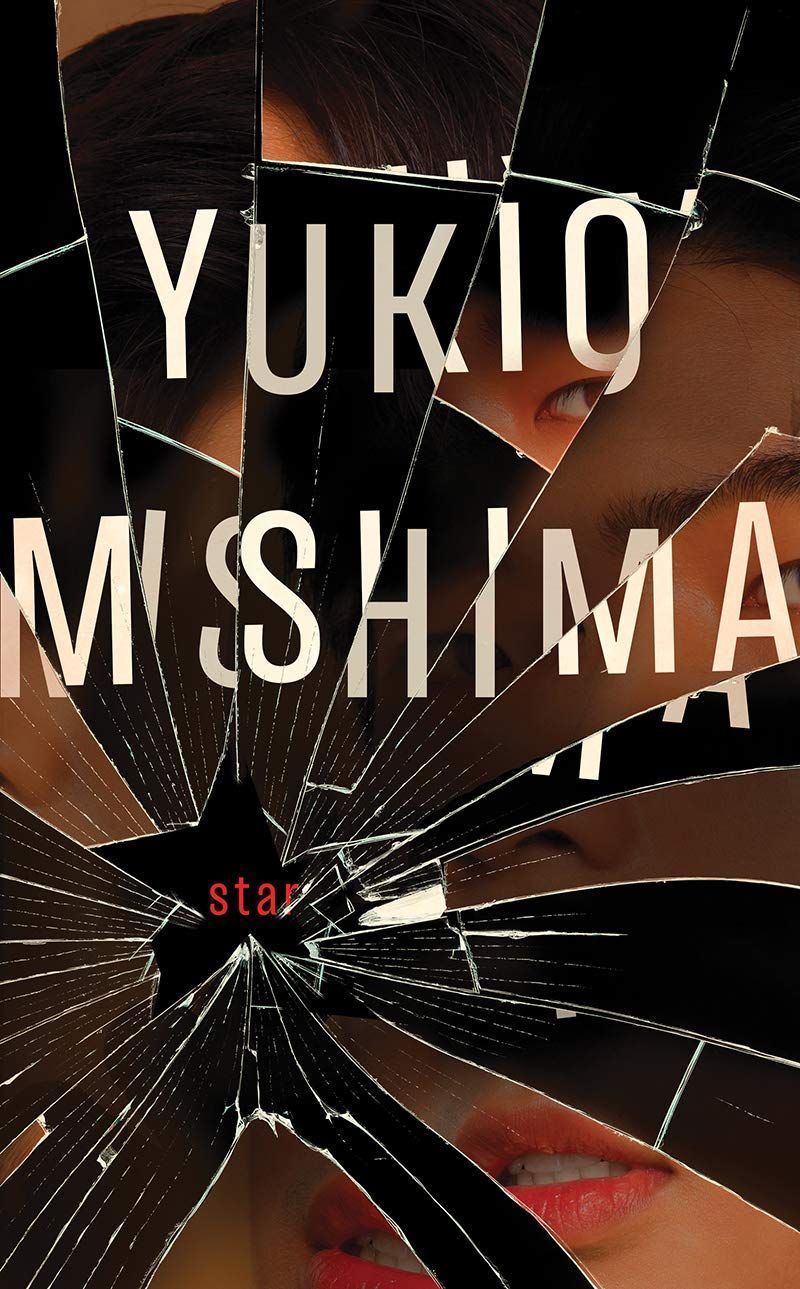

Star by Yukio Mishima. New Directions. 80 pages.

IT SEEMS BOTH the great comedy and the great tragedy of Yukio Mishima’s life that hardly any of his work’s plots live up to his death. While anything but a wallflower, Mishima didn’t have the topsy-turvy life of a Daniel Defoe or a Herman Melville — he was neither jailed and pilloried nor on the hunt for roly-poly whales. But when it comes to spectacular deaths among the writers of the world, Mishima is top tier.

The story goes that he didn’t wait for the ink to dry on his final entry in his Sea of Fertility tetralogy, The Decay of the Angel (published posthumously in 1971), until he made plans for his suicide, in public and full view of the world, when he killed himself after a failed putsch that might never have been wholly political and always a private death masquerading as a public spectacle.

When Mishima returned from the last balcony that his 45-year-old eyes would ever see on that cool November morning in 1970, having given a fervent speech to urge Japan’s return to samurai glory and having been scorned by soldiers annoyed about their curtailed lunch breaks, Mishima committed seppuku — the traditional suicide of the samurai warrior — in the Eastern Command of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces in Tokyo. Afterward and according to tradition, Mishima’s head was severed from his body by an apprentice.

At the time of his death, Mishima was a celebrity in Japan and one of the most widely read and revered writers of his time. In just over 20 years, he had amassed an impressive oeuvre of novels, plays, short stories, essays, poems, and even films as both actor and director. With some of the most impassioned, reflexive, and violent works of modern Japanese literature to his credit, Mishima put the finishing touches to his legacy by ending his life in a way that matched his work — life imitating art, as if he had turned his work inside out, had allowed his literature to spill over into his life and shower the images of suicide and violence on his existence in the most spectacularly public way possible. Readers and followers of Mishima had long known that suicide had always been in the cards for him. It was the only card for the man called Mishima, the man who called himself Yukio Mishima — the pen name, the mask, of Kimitake Hiraoka. After a lifetime of semi-autobiographical works and carefully staged glimpses of the man behind the mask, at the end Mishima had shown the world — just about literally — his insides.

The work is a steadily building oeuvre of obsessional finesse, often so finely wrought that one might forget the staggering swiftness with which he published dozens of novels and plays in but two decades. Wedged somewhere between the great novel that concluded his earlier period generally concerned with love, lust, and sensuality (while violence is never absent), The Sound of Waves (1954), and the master work that initiated his later period spiraling into violence, terror, and suicide (while sex is never absent), The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea (1963), is a small novella that seems like a reprise of preoccupations that drove his earlier work, while announcing the defining obsessions of his final years.

The novella Star, first published in Japanese in 1961, gives an apt introduction to Mishima’s preoccupations, but should be viewed as no more than an introduction to his greatness. Woe to those who go gently into that good night without ever having read Confessions of a Mask (1949), Mishima’s first and largely autobiographical novel, or the most perfect entry in his Sea of Fertility tetralogy, Runaway Horses (1969). In Star, Mishima fuses his major theme of the mask, the public role all humans are destined to play out, with the theme of suicide, an act which Mishima considered a work of art. All of his work is punctuated by suicide, and it is peopled with masks, with people knowing they are nothing but masks, who are aware that the center doesn’t hold because there is no center, that character is a flowing fixture, a paradoxical constancy and a definite variable, always.

In Star, which arrives in the first ever English translation by Sam Bett, the mask at the center of the book is nearly literally a wearer of masks, an actor who narrates this tale, and who might be fictionalizing his life as much as he is fictionalizing his role. Mishima’s curt style, devoid of needless realistic description and in favor of subtle suggestion, vexingly blends Rikio’s life with Rikio’s role. The role he is acting is that of a tough Yakuza in a mediocre B-movie similar to the ones in which Mishima had acted himself. Mishima writes the task of waiting around for another scene, another take, so vividly that it is impossible not to feel what Rikio feels, that the role supersedes the life.

Rikio’s life is nearly spent, even if he is a young man. But he is stuck “at twenty-three, an age when nothing is impossible” — except, of course, an authentic life, especially to an actor: “My physique was rugged and my build was solid, but the old power was escaping me. Once a mold has cast its share of copies, it cools and loses shape and is never strong again.”

While Rikio narrates, juxtaposing the mundane task of waiting around for the shooting of a scene against the extraordinary depth of his reflexive soul, Mishima constantly puts him in scenes where he is the mold for copies: he is filmed, he is seen in mirrors, he has a cardboard cutout of himself for company, and he is surrounded by nearly as many photographs of himself as Norma Desmond was. Mishima explores the idea that seeing is existing, as the old Bishop Berkeley would have it, esse est percipi, but that being seen, like existing, also wears one down, as if each eye laid on a person scraped off a tiny bit of their essence. As a result, Rikio is constantly fatigued; he is sleep-deprived and worn down, all too quickly burned down, like Millay’s candle, and this weariness is highlighted as an effect of his work.

And yet, Rikio’s author equally wears him down: Mishima’s probing style chips away at his character, as if to burn away the dross and arrive at Rikio’s hardened core. Rikio, like the reader, must discover that there might not be anything beneath the surface, that most masks stripped away reveal nothing but a gaping hole, that the mask might be the core. But like Robert Musil, Mishima imagines a man without qualities by writing a prose of such stupendous qualities that, in this case, I found myself unwittingly reading aloud in public the beautifully refined phrases, to the frowning faces of my fellow subway passengers or café companions. A moment Mishima would have cherished.

One such example of the exquisitely crafted style comes late in the story, when Rikio wanders around the film studio and, amid the industrial nondescript non-space, observes the production company’s “sapphire flag flapping from a pole at the peak of the roof.” This minor observation becomes the novella’s epiphanic high point, a mundane moment made magnificent through its structural placement after the fray of the plot has subsided, made beautiful through the author’s heightened sensibility:

The flag spasmed on the breeze. Just as it would seem to fall limp, it whipped out smart against the sky. Its cloth snapped between shadow and light, as if any moment it would tear free from its tethers and fly away. I don’t know why, but watching it infused me with a sadness that ran down to the deepest limits of my soul and made me think of suicide. There were so many ways to die.

Mishima’s sensibilities are too complex to be boiled down to mere symbolism; the flag is not just a stand-in for humanity’s hopeless condition of being simultaneously animated and static, like a flag tied to the pole of existence while violently yearning to flap free and thereby terminate itself. The flag punctuates and accentuates Rikio’s yearning, his extreme desire for both beauty and death, and how sometimes these are inextricably interconnected.

What has made this scene so pivotal, so delicate, is what has preceded it: moments of chaos and desperation in Rikio’s life and the lives that surround him. He is entangled in a peculiar relationship with his assistant Kayo, seemingly a sibling relationship, but also a sexual one. It is an archetype of relationships in Mishima, in that it always swings from teasing to tenderness, from ridiculing to longing. It is Kayo in whom Rikio will ultimately confide and confess his “unreasonable urge to die,” but only after the novella has steered through a suicide attempt on the film set by a young woman who is infatuated with Rikio’s public persona and who tries to gain his attention, at which she succeeds.

In this story so consumed by sight and seeing, it’s when Rikio sees the young woman convulsing with pain upon being rescued by a doctor, that Rikio understands the meaning of what a successful suicide attempt might consist of, how it quite simply offers a moment out of “the disgraces of this bright and garish world.” The twist that Mishima puts on suicide is this: because it is a planned, staged event, it doesn’t lack authenticity. On the contrary, it is true, it is whole, but at the same time, it is also an event of pure artifice. Rather than slipping into death unwillingly, suicide is the one act of death that is precisely that, an act, that is meaningful because it is based on choice, an act that comes closest to acting out what is otherwise a non-event. And this is what, to Mishima, turns it into an act of beauty.

In Star, Mishima is able to explore how seeing and being seen are acts and events of extreme privacy, which are suddenly part of public spaces and spectacles. Acting is one of the few professions in which its practitioners are continually asked to have private moments in public, and Mishima’s Star asks if every person is wearing a mask, is playing a role, and is an actor.

Rikio and his stardom are torn between the need to be seen and the necessity to be hidden from view: “It’s better for a star to never be around. No matter how strict the obligation, a star is more of a star if he never arrives.” Therein lie the star’s paradox and Rikio’s torment. It is Kayo who, perhaps, from watching, seeing the star without being one herself, is able to put into words the curious paradox of Rikio’s existence:

For a star, being seen is everything. But the powers that be are well aware that being seen is no more than a symptom of the gaze. They know that the reality everyone thinks they see and feel draws from the spring of artifice that you and I are guarding. To keep the public pacified, the spring must always be shielded from the world by masks. And these masks are worn by stars.

“But the real world is always waiting for its stars to die. If you never cycle out the masks, you run the risk of poisoning the well. The demand for new masks is insatiable.

These words might well be read from the vantage point of our image-ravaged era, our celebrity-strangled world, but like all great literature, Mishima’s complexity encourages more ahistorical readings, as well. He doesn’t let his readers off the hook too easily, doesn’t allow a one-sided reading, too narrowly limited to one aspect of modern life and culture. Through Rikio he introduces us to a shallow character, who is only shallow on the surface, who is capable of deep reflections about life, death, art, and culture, but who is also a deeply nihilistic character, reminiscent of Dostoyevsky’s people, bitten by self-doubt and self-destruction, haunted and hounded by fragmentation and disintegration, but also secretly desiring it. Ultimately, perhaps, he finds beauty in the disintegration, because that might very well be his last hideout.

Even if Star is a relatively minor work in the pantheon of Mishima’s greatness, it is an exquisite contemplation of existence and death, and Mishima’s prose is extremely powerful and the translation finely executed. At times, Sam Bett exhibits a wonderful punning playfulness, as when he has Rikio strike “a grave tone” during a discussion of death, or when he scatters the word “star” throughout the story via an amplified frequency of words in which it’s hidden, as when at a key moment Kayo’s voice is “startling” Rikio awake. Bett’s skillful rendering of Mishima’s beautiful prose is so assured that it is surprising at times to find phrases and expressions that stultify the reading, such as “take a breather,” “ass-backwards,” or when sexual excitement is actually implied through the international code for brainlessness: “Hubba hubba!” These instances of seemingly slapdash Westernization do indeed jar. But one should remember that the modern Japan which Mishima was imagining and representing in this novella (and in other works) is a culture that has itself been deeply jarred by its blind adherence to the stickiest aspects of Western culture. In fact, the title of the novella in the original Japanese is the English loanword sutā (“star”). This rift in his culture, which Mishima perceived everywhere, was in part what made him seek refuge in the rituals and traditions of the samurai, even if he did love cheap American films. And so, it is entirely appropriate — in the aesthetic rather than the moral sense — that his severed head donned a patriotic 14th-century motto, which was captured on film, photographed for the front page of the evening paper.

¤

LARB Contributor

Jan Wilm is a novelist and translator based in Frankfurt, Germany.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Sexual Abuse and Critical Abuse: On Christian Kracht’s “The Dead”

Jan Wilm considers Christian Kracht's latest novel to be translated into English as well as how his critics misjudge his works.

The Sad March of the Japanese Left

The Old Left of Japan soldiers on in its denunciation of nuclear power.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!