Acid’s First Convert, Cary Grant: On Edward J. Delaney’s “The Acrobat"

James Penner on Edward J. Delaney’s 2022 novel “The Acrobat."

By James PennerNovember 2, 2023

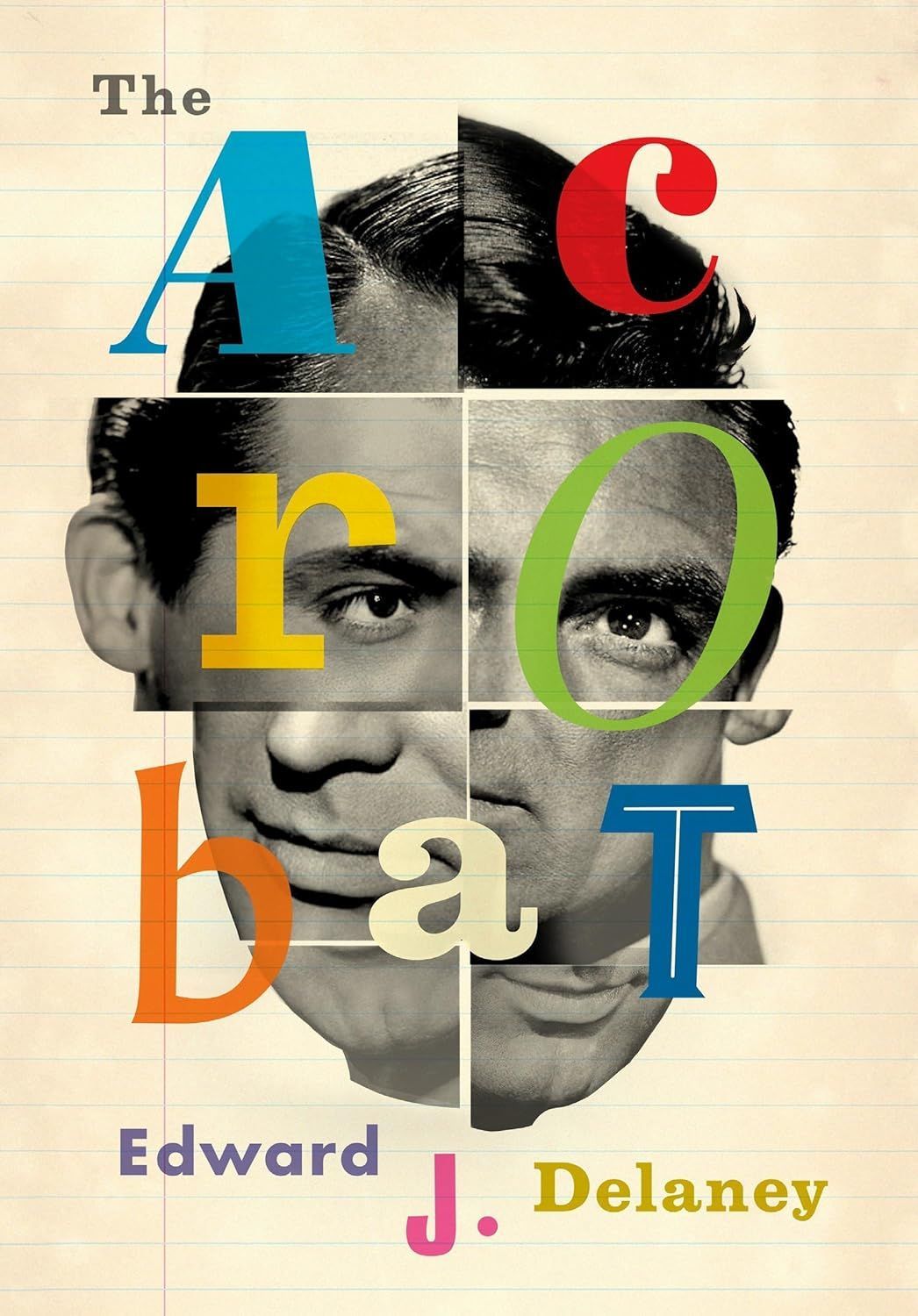

The Acrobat by Edward J. Delaney. Turtle Point Press. 280 pages.

WHEN CARY GRANT was not shooting a film, he went to the Psychiatric Institute of Beverly Hills every Saturday morning in 1959, using the back entrance to avoid being seen. In a small, beige-colored room modestly furnished with easy chairs, a sofa, and a phonograph player, he received five Sandoz LSD pills and a glass of water. Once the mind-altering drug took hold, the Hollywood icon started crying as Dr. Mortimer Hartman guided him through a psychic minefield: his traumatic childhood years in Bristol. The Hollywood icon learned that these painful memories could be repressed for a while, but they could not simply be willed away. LSD was therapeutic in the sense that it enabled him to reframe his traumatic experiences. After many tears, Grant’s catharsis would often culminate in feelings of ecstasy as Hartman played selections from Rachmaninoff and Chopin on the phonograph player. After the LSD psychotherapy session ended, Grant would be driven home by his driver, and as he watched the afternoon traffic go by his car window, he felt serene.

From 1958 to 1962, Grant had over 100 LSD sessions, and he credited LSD and Hartman with “saving his life.” Grant’s intense LSD psychotherapy sessions of 1959 provide a template for Edward J. Delaney’s 2022 novel The Acrobat—a new addition to the rather obscure genre of the LSD novel. LSD novels typically feature a protagonist who discovers mind-altering drugs that provide revelations and facilitate self-discovery, but these substances also inevitably steer the protagonist into serious conflict with the values and institutions of mainstream society. Once the conflict ensues, the psychedelic hero/heroine inevitably has to renegotiate their relationship with a repressive society that often questions the protagonist’s sanity. In other words, the trip ends and the transformed hero/heroine has to deal with “reality.” The most famous LSD novel is undoubtedly Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1971), but there have been several others that explore similar terrain: James Fadiman’s The Other Side of Haight (2001) and, most recently, T. C. Boyle’s Outside Looking In (2019), which examines the background to the scandal surrounding the Harvard Psilocybin Project of 1963.

As well as being historically interesting, Delaney’s novel is topical because it sheds light on the current “psychedelic renaissance” of the past 15 years. As psychedelics begin to gain medical respectability and FDA approval, Delaney’s novel asks the contemporary reader, Can we learn something from Cary Grant’s cathartic trips?

The title of Delaney’s novel is derived from Grant’s earliest occupation when he first traveled to the United States as an acrobat and performer in 1920. In the context of Grant’s midlife crisis of the late 1950s, the term refers to his ability to navigate his way through the psychic terrain of his past. Appropriately, the story begins with Grant in mid-flight, psychedelically speaking:

The Acrobat [Grant] revels in sensation, bright lightness made of molecules binding with imagination. He savors the blade of horizon cutting around him, a somersaulting azimuth, orbiting him as planets orbit a bright and burning center.

He inhales a thin and bracing air. […] [H]is mind makes its vaults and flips, now that the LSD has taken its fullest hold of him. Dr. Hartman sits in his chair, nearby, Virgil to his Dante.

Delaney’s prose captures the elasticity of expanded consciousness but also the unpredictable and surreal moments that inevitably transpire.

Grant’s sessions with Hartman quickly reveal that the actor has conflicting selves within his psyche. Although he was born Archibald Leach, a working-class lad from Bristol, he was persuaded to give up this name in the 1930s when he was hired by Paramount Pictures. When the movie studio christened him “Cary Grant,” he had no qualms about ditching “Archie Leach.” After years of playing a suave socialite with a mid-Atlantic accent, he began to feel like a fraud; it became increasingly difficult to live with the artifice he had created. In Delaney’s novel, Archie is at war with Cary Grant during his high-dosage LSD trips. During one intense session, Grant is confronted by all the characters from his cinematic and theatrical past. Grant remarks to Hartman: “Every character I ever played, together like a wild unhinged mob, coming to do me in. I always controlled them, but now they’ve broken free and they want to destroy me. Look at me. I’m still shaking.” Grant’s nightmarish trip reveals the dark side of self-reinvention and the importance of acknowledging the self that has been repressed and devalued.

In Delaney’s novel, Grant’s LSD therapy sessions function as extended psychoanalytic flashbacks that reveal his destructive behavior in each of his three failed marriages. His most recent marriage to Betsy Drake is unraveling when Grant decides to undergo LSD psychotherapy. Drake has had great success with Hartman, and Grant is curious about this new drug, which at the time is completely legal. One of Grant’s initial breakthroughs is that his marital conflicts and problems with women in general stem from his traumatic experiences with his mother. Grant learns to reframe the truth about her disappearance in 1915: Grant’s father Elias had actually placed her in an asylum in Fishponds, Bristol, and told his 11-year-old son that she was “going away for a while.” Although Grant learns the truth some 20 years later, he cannot overcome the debilitating feeling that he was abandoned by his mother.

While doing LSD psychotherapy, Grant detects a clear pattern of behavior in each of his marriages: he was unconsciously punishing his mother by being cold and indifferent to each of his three wives. Thus, Grant learns to recognize his self-destructive forms of behavior: “I had to face things about myself which I never admitted […] Now I know that I hurt every woman I ever loved. I was an utter fake, a self-opinionated bore, a know-it-all who knew little.” Some of Grant’s speeches in the novel are taken from interviews he did in 1959 and 1960. These passages lend historical credibility to Delaney’s depiction of Grant’s LSD-inspired transformation. In one interview, Grant also admits, “I was hiding behind all kinds of defenses and vanities. I had to get rid of them layer by layer. The moment when your conscious meets your subconscious is a hell of a wrench.”

Grant’s therapy sessions also contain light and humorous moments. In one session with Hartman, Grant’s “penis [becomes] a rocket ship, roaring into space. He feels the heat and light and noise, a powerful thing; it is neither elating or disturbing, just what seems a fact.” Grant is quite puzzled by his vision and asks Hartman to interpret the phallic symbolism. Hartman is reluctant to impose one definitive interpretation: “[Y]our rocket has served your own needs, but what are the new realities? […] The mind constructs scenarios to help you see the truth you might not want to admit.” For Hartman, LSD is a facilitating agent that allows the patient to observe past behavior without shame or remorse.

In most LSD novels, the protagonist eventually comes into conflict with the values and institutions of mainstream society. This moment occurs in The Acrobat when Grant cannot resist praising the effects of his LSD psychotherapy to a journalist. In a routine press event that was supposed to be about his new submarine film Operation Petticoat (1959), Grant goes off script and describes how LSD has completely changed his life. After the interview is finished, Grant and his handlers worry that his revelations about a drug that produces hallucinations will affect his public image; they also worry that the interview will produce negative publicity for the upcoming release of North by Northwest that same year. In this case, however, the public was actually fascinated with Grant’s description of his LSD trips. The truth is that few people had heard of LSD in 1959 and the drug did not yet have a bad reputation. Grant learns that he needs to stop obsessing about his public image.

Delaney’s novel concludes with Grant breaking out of the eggshell identity that he and the Hollywood studio system have created. The Bristol-born actor decides to liquidate “Cary Grant”: “I’ll hang him up in the closet like a suit I don’t care to wear anymore.” In one of Grant’s final LSD sessions, Hartman asks why he has never had children. “The thought terrifies me. I have no idea why. […] I was raised by two people who had no idea how to look after a child, or possibly had no interest. Why do I think I’d do any better?” Hartman gives Grant the answer that he has been searching for: “Maybe you’d do better for exactly that reason.” The novel ends with Grant deciding to give up screen acting and embrace fatherhood.

Since The Acrobat ends in 1959, it leaves out Grant’s post-1959 years. Although Grant’s last official LSD psychotherapy session was in 1962, the Hollywood icon obtained his own private stash of LSD and continued to trip for at least another decade. Despite his post-LSD optimism, Grant would go on to have another disastrous marriage, this time with Dyan Cannon in 1965. However, Grant would also finally become the proud father of a daughter, Jennifer. During his marriage, Grant would often urge Cannon to take LSD with him, but we know from her memoir Dear Cary: My Life with Cary Grant (2011) that these trips did not go well for her. While they were dating, Grant arranges for a three-way LSD trip with Cannon and Hartman. The trip goes well at first, but it turns dark when she looks at Grant and he begins aging right in front of her eyes:

I looked at Cary. I suddenly saw him as a boy of ten, twelve, fourteen … It was as if the years had first rewound, and now they were fast-forwarding. Cary was turning into an old man in front of my eyes. His skin sagged, his eyelids drooped, his neck hung like tangled bedsheets …

“I don’t think I like this,” I said. “Make it stop.”

Cannon’s bad trip was about her repressed fears about their 33-year age difference. In all likelihood, she would outlive Grant, and her fear of Grant’s aging triggered her bad trip. As a facilitating agent, LSD has the potential to reveal disturbing truths that have been repressed by the conscious mind; this is also why it can be beneficial to have a therapist nearby during the most fraught moments.

Delaney’s engaging novel provides a time-capsule view of 1959, shedding light on the utopian moment before psychedelics became stigmatized. In 1959, there was no counterculture, and psychedelics were simply a new drug that could assist psychotherapy. Between 1959 and 1961, the story of Grant’s conversion to LSD psychotherapy would be covered by several mainstream publications—Look, Time, and The Washington Post—as well as several women’s magazines, such as Good Housekeeping and Ladies’ Home Journal. In each case, the coverage was entirely favorable. However, the FDA began restricting access to LSD in 1962. Hartman and other prominent L.A. physicians, such as Dr. Oscar Janiger, were no longer able to use LSD for psychotherapy. * When the Harvard drug scandal of 1963 hit, LSD’s honeymoon with the press was definitely over. By the mid-1960s, a moral panic ensued, with psychedelics being linked to “bad trips” and the emergence of “hippies” and the anti-war movement. LSD would be banned in 1966 and declared a Schedule I drug alongside heroin and crack cocaine in 1968.

Although The Acrobat does not cover the 1960s, it successfully reimagines the historical moment when LSD was legal and used for therapeutic purposes. The psychedelic accoutrements that appear in the novel—wearing black sleep masks, playing classical music, and having a sitter nearby—have all come back and have been incorporated into the FDA-approved psilocybin trips administered by Johns Hopkins University Medical School, New York University, and UCLA over the last 15 years. Although Delaney’s novel captures the optimism and excitement of the early years of psychedelic therapy, it also documents the rhetorical power of celebrity endorsement. For the readers of Ladies’ Home Journal and Good Housekeeping, Cary Grant’s LSD trips were a source of fascination and romance. Each article stresses how LSD had given the aging movie star a “second youth” and made him a more sensitive lover.

If many historical discussions of LSD in the 1960s inevitably focus on familiar tropes—hippies, flower power, and the Summer of Love—Delaney’s supple novel manages to illuminate a moment of psychedelic history that has often been overlooked: the emergence of LSD psychotherapy just before the moral panic took hold. It also presents a convincing portrayal of Grant’s private psychedelic experiences and documents how LSD psychotherapy helped the Hollywood icon radically reframe the traumatic experiences of his childhood.

¤

* Dr. Oscar Janiger, a key figure in psychedelic history, promoted using LSD to enhance creativity. When Dr. Mortimer Hartman’s medical license was suspended, Cary Grant continued to trip at Janiger’s office on Wilton Place in Los Angeles in 1962.

¤

LARB Contributor

James Penner is the editor of Timothy Leary: The Harvard Years (2014) and the author of Pinks, Pansies, and Punks: The Rhetoric of Masculinity in American Literary Culture (2011).

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Untold Story of the CIA’s MK Ultra: A Conversation with Stephen Kinzer

Stephen Kinzer discusses his new biography, “Poisoner in Chief: Sidney Gottlieb and the CIA Search for Mind Control.”

The Anatomy of the LSD Romance in the 1970s: On Errol Morris’s “My Psychedelic Love Story”

James Penner analyzes the life and times of Joanna Harcourt-Smith and Errol Morris’s recent film about her, “My Psychedelic Love Story.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!