The Anatomy of the LSD Romance in the 1970s: On Errol Morris’s “My Psychedelic Love Story”

James Penner analyzes the life and times of Joanna Harcourt-Smith and Errol Morris’s recent film about her, “My Psychedelic Love Story.”

By James PennerJanuary 22, 2021

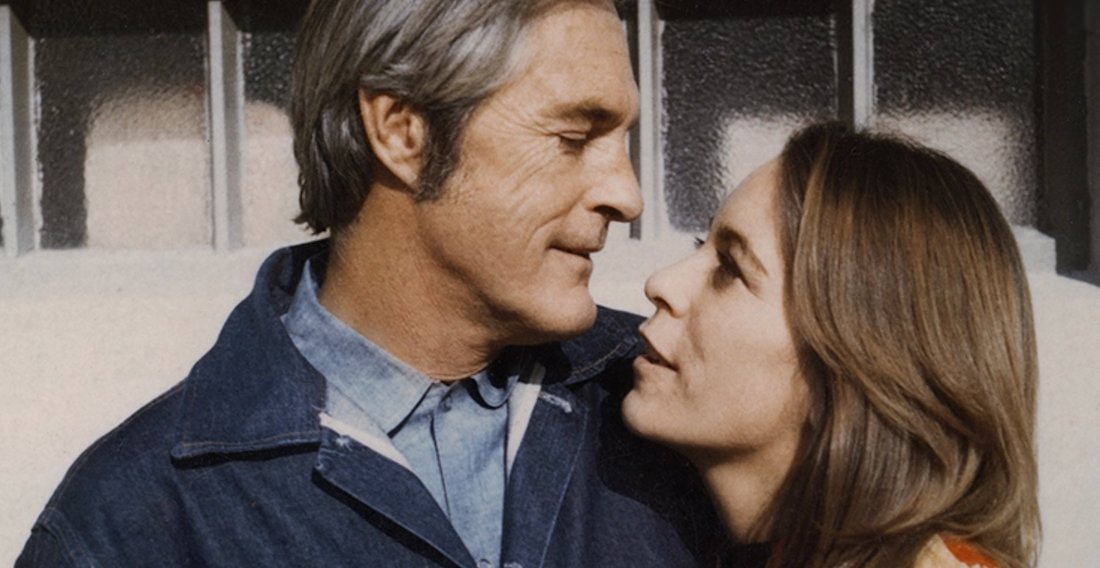

AT THE BEGINNING of her 2013 memoir, Joanna Harcourt-Smith jokingly remarks that she had always fantasized about sleeping with three men: JFK, Jimi Hendrix, and Timothy Leary. By 1970, the first two were dead, so she gravitated toward the latter. While her joke appears to be cocktail party banter, Harcourt-Smith, a Franco-Swiss socialite-turned-author, is a fantastically strong-willed woman able to bend reality to her wishes. Errol Morris’s new film, My Psychedelic Love Story, boldly chronicles Harcourt-Smith’s troubled childhood and her intensely fraught romance with psychologist and psychedelic drug advocate Timothy Leary in the true decade of excess: the 1970s. The film is centered around Harcourt-Smith’s whirlwind romance with Leary, which culminates with Leary’s capture and imprisonment in Afghanistan in 1973. The film also documents Harcourt-Smith’s three-and-a-half-year campaign to free Leary of a 25-year prison sentence.

The narrative arc of Morris’s new documentary resembles the chaotic trajectory of an intense LSD trip: ecstatic highs and Dantean lows with a miraculous release from bondage at the very end. And like all mind-bending LSD trips, My Psychedelic Love Story asks the crucial question when it’s finally over: “What the hell just happened?” Harcourt-Smith has not been able to satisfactorily answer that question some 45 years later. At the beginning of My Psychedelic Love Story, Joanna speculates that she might have been manipulated by CIA operatives seeking to ensnare Leary in a trap. The countercultural icon was, after all, wanted by the Nixon administration, the FBI, and the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD). Although My Psychedelic Love Story asks more questions than it can answer, it still ends up being an enormously satisfying cinematic experience.

Like many of Morris’s films, My Psychedelic Love Story defies generic categorization; it’s a love story wrapped in an espionage novel, with LSD constantly blurring the viewer’s sense of historical truth and reality. What it is, undoubtedly, is a Morris picture. It further evokes his 2010 film Tabloid, which also dealt with an obsessive love story and centered on a charismatically unhinged protagonist. And it can also be treated as a quirky companion piece to his miniseries Wormwood (2017), a chronicle of the CIA mind-control program known as MKUltra that went terribly wrong when a CIA chemist was dosed unknowingly and committed suicide. However, in Morris’s six-part docudrama, the alleged “suicide” is revealed to be a murder that has been covered up by the government authorities. Like Wormwood, My Psychedelic Love Story is a probing psychoanalytic journey into its subject’s dislocated psyche, attempting to lay bare the political and psychological forces that shaped Harcourt-Smith’s chaotic life in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Lastly, My Psychedelic Love Story also evokes The Thin Blue Line (1988) and Standard Operating Procedure (2008) in the sense that it examines how prison authorities are apt to use torture and manipulation to make subjects “confess” and tell the stories that they want to hear.

My Psychedelic Love Story is also an innovative film that attempts to transform the talking-heads format that is ubiquitous in documentary filmmaking. It begins with a lone talking head, Harcourt-Smith, pressing the button on a reel-to-reel tape player that plays the voice of Timothy Leary from Vacaville prison in 1974. The opening scene can be considered an homage to the old-fashioned talking-heads approach to documentary filmmaking, since Morris’s protean film slowly transforms before the viewer’s eyes as Harcourt-Smith narrates her tale. Morris and graphics artist Jeremy Landman punctuate Harcourt-Smith’s dialogue with symbolic objects — handcuffs, cars, revolvers, taxis, martini glasses — placed on colorful LSD blotter paper, ominous tarot card images, and color-drenched newspaper headlines that move across the screen in kaleidoscopic slow motion. Although most filmmakers simulate psychedelic experiences by showing rapid sensory-overload sequences, My Psychedelic Love Story slows it down and features a series of striking images that convey the internal life of Harcourt-Smith during her encounters with Leary in the winter of 1972. With help from his creative team (editor Steven Hathaway and music director Paul Leonard-Morgan), Morris has created a mise-en-scène that hypnotizes the viewer with visual and aural cues (the sounds of a Zippo lighter or a gun clicking). The end result is a cinematic style that is bewitching, but also germane to the story that Morris wants to tell; My Psychedelic Love Story is, after all, a grandiose tale about the alteration of consciousness.

The narrative of My Psychedelic Love Story is concerned with unraveling Harcourt-Smith’s past and her complicated family history. She was the daughter of Cecyl Harcourt-Smith, a silver-haired Etonian aristocrat who was a commander in the Royal Navy. Her mother, Marisya Ulam, was an attractive and domineering Jewish heiress whose family left Poland and settled in Paris in the 1930s. Marisya and her family eventually settled in Switzerland to escape from the Nazis, but many of her relatives in Poland were not so fortunate. Cecyl’s marriage to Marisya was brief, and he was never actually present in Joanna’s life. Although Joanna grew up in extreme wealth, her childhood was an unhappy one. In her 2013 memoir, Tripping the Bardo with Timothy Leary, Joanna Harcourt-Smith described her mother as a woman who “spoke seven languages and in her rage would effortlessly slide from one language to another for words with which to abuse me. Sometimes, even seven languages did not seem to suffice.” But perhaps the most disturbing episode of her youth was being molested by the family chauffeur at the age of 11. According to Harcourt-Smith, when she described the experience to her mother, she replied, “Lies won’t get you what you want, Joanna,” and then, “good servants are hard to find.” These experiences pushed her to search for a father figure who could heal her trauma.

The paths of Harcourt-Smith and Leary crossed when the ex-Harvard psychologist was living in exile in Switzerland in 1972. After his successful escape from the California Men’s Colony in San Luis Obispo in September 1972, Leary was living incognito in a modest Swiss chalet. Harcourt-Smith first learned about his whereabouts from her former lover Michel Hauchard, an affluent Swiss arms dealer with CIA connections. The CIA had been closely monitoring Leary’s movements in Switzerland and was aware that he might flee because his Swiss visa would be expiring in a few months. When Hauchard related the details of Leary’s prison escape to Harcourt-Smith, she became fascinated with the renegade psychologist; she thought to herself, “This is so exciting, I always wanted to be with an outlaw.” Her comment reveals her youthful naïveté and attraction to danger. Little did she know that her association with Leary would turn her life upside down.

Prior to meeting Leary, Harcourt-Smith had a habit of getting pregnant and ending up in marriages that she didn’t really want to be in. After two short-lived marriages and giving birth to a daughter and a son, she realized her "destiny" lied elsewhere. When she learned that Leary was living near Lucerne, she found his phone number in Michel Hauchard’s leather-bound address book and called him up. When Leary first spoke with her on the phone, he was worried that she might be a CIA plant trying to lure him into a trap. When Harcourt-Smith finally encountered Leary in a Kunsterhalle [art exhibition gallery] in Lucerne, their meeting could be described as “love at first sight,” or as a case of mutual obsession. When they are alone, Leary remarked, “You have come to free me and bring me back to America.” Although she did not know exactly what he was talking about, she would soon find out.

Although Leary and Harcourt-Smith took a lot of LSD together, she is not a drug-addled interview subject. Her emotional memories of her love affair with Leary are indelibly etched into her brain. Her description of her first sexual experience with Leary is particularly vivid: when the two lovers are tripping, Harcourt-Smith begins to undress, and before they make love, Leary places bracelets, necklaces, and various pieces of Indian jewelry all over her naked body and declares, “You are Lakshmi” [the Hindu goddess who nurtures all life]. Then the psychologist shows her a Life Magazine article from 1972 that contains pictures of the human brain. As Leary and Harcourt-Smith marvel at the black-and-white photographs of the brain, Leary points to the photographs and explains, “That is where I am going to make love to you.” This is the first of many lovemaking sessions that lead Harcourt-Smith to declare that they were “truly bonded.”

All in all, LSD bonding sessions would continue for some 49 days as Leary and Harcourt-Smith crisscrossed Switzerland and Austria in Leary’s canary yellow Porsche that was purchased with advanced royalties from his soon-to-be-published book, Confessions of a Hope Fiend. Although their relationship certainly could be described as drug-induced escapism, Leary was always aware that the BNDD was monitoring his movements and that he would probably be caught eventually. What is perhaps most striking about My Psychedelic Love Story is the film’s uncanny ability to recreate Harcourt-Smith’s memories — of LSD trips and the highs of self-destructive romance — so evocatively.

The second part of My Psychedelic Love Story deals with coming down from the drugs and the sex and experiencing the ultimate bummer: Leary’s being captured in Kabul by Nixon’s BNDD. Prior to capturing Leary, Nixon had famously described the ex-Harvard professor as “the most dangerous man in America.” Harcourt-Smith’s narrative suggests that Nixon’s capture of Leary in Kabul was timed to coincide with the president’s second inauguration celebration in January 1973. The public defeat of Leary, an LSD proselytizer and a vocal opponent of the Vietnam War, had great propagandistic value for Nixon’s “Law and Order” platform. As Leary is put on trial and imprisoned in 1973, Joanna begins to act as Leary’s advocate for his release. This is the point in the film where she shows her grit and determination.

Harcourt-Smith embarks on a Kafkaesque journey into American politics and the nation’s legal system, in which she learns that the Nixon administration is using the Leary trial to secure additional funding for a new government body: the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). Harcourt-Smith also learns that the ex-Harvard psychologist is regarded as an “ideological trafficker” and is placed in solitary confinement for four and a half months, given weekly injections of antipsychotic drugs without his consent. According to Robert Greenfield’s biography of Leary, on one occasion that Harcourt-Smith visits Leary in prison, she notices that Leary’s mane of hair has been shaved off and that the prison barber has left encrusted blood on his skull. When she realizes that Leary “may lose his mind” from forced Thorazine injections, she urges the countercultural icon to become a government informant. (Given the amount of torture he endured in 1973 and 1974, it’s a wonder that Leary held out as long as he did.)

When Leary becomes an informant, My Psychedelic Love Story becomes a meditation on the malleability of the human will under extreme duress and imprisonment. Morris highlights an evocative moment from Harcourt-Smith’s childhood when she was pressured to testify against the family’s gardener. Although she knew that the gardener had not touched “[her] pee pee,” the police used pressure to make her tell them what they wanted to hear. At this point, My Psychedelic Love Story suggests that Skinnerian-minded authorities can elicit a confession by exerting psychological pressure on the subject. Leary’s decision to become a “narc” is predicated on the fact that he would otherwise spend the rest of his adult life in prison; for the most part, Leary gave the DEA and the FBI information that they already had. Leary, after all, had been living in Europe for nearly three years, so whatever information that he had about the Weather Underground was outdated. [1]

The film ends with Leary’s release from prison in April 1976 and the demise of Leary and Harcourt-Smith’s relationship. Although the couple is reunited and renamed “James and Nora Joyce” when placed in the Witness Protection Program in New Mexico, their relationship quickly disintegrates into alcoholic fights and nasty recriminations. After one particularly awful fight, as Harcourt-Smith remembers it, Leary drove away from their A-frame house in New Mexico in a used Ford Pinto and never came back. There is no happy ending in My Psychedelic Love Story. Rather, the narrative of the film is Harcourt-Smith’s quest to heal her “pulverized” psyche and find out who she really is. Although Harcourt-Smith’s relationship with Leary could be described as an open wound, the film makes it clear that Harcourt-Smith never regretted her affair with Leary; however, she was profoundly saddened when their relationship did not continue once Leary was released from prison.

Morris’s film is especially powerful because it exposes the insanity of the war on drugs by documenting its casualties. I wish I could say that the subject matter of My Psychedelic Love Story is ancient history, but Americans are still living under Nixon’s Controlled Substances Act (1970), a federal law that considers cannabis, LSD, and magic mushrooms to be “dangerous drugs” with “no accepted medical use.” Although many states continue to legalize and decriminalize cannabis, the CSA is still often used by law enforcement to harass and subjugate people of color and psychedelic healers, especially in states where cannabis is still illegal. The fact that Leary was given a 25-year sentence for possessing a minuscule amount of cannabis will undoubtedly come as a surprise to many young people. [2] That said, My Psychedelic Love Story is ultimately not about Timothy Leary and his imprisonment. It’s a film about a woman who survived and has been trying to piece together her story and figure out what really happened to her.

For many decades, Harcourt-Smith had a bad reputation in psychedelic circles. In the 1970s, many suspected that she was a CIA agent and frequently greeted her with misogynistic abuse. In her post-Leary years, she became sober and eventually wrote her engaging autobiography. She gave up alcohol and other addictive drugs, but she continued to be an advocate for psychedelics and their healing potential. Harcourt-Smith’s story is an important one because historians of psychedelic culture have too often focused on the tales of larger-than-life men — Aldous Huxley, Alan Watts, Ken Kesey, Hunter S. Thompson, and, of course, Leary. To more fully understand the era, we need to talk more about the psychedelic heroines who lived equally extraordinary lives. For many decades, Harcourt-Smith’s story has been relegated to the margins of psychedelic history. Few people in the publishing industry took her story seriously, and all the major publishing houses rejected her memoir. The rejection letters that Harcourt-Smith received tacitly suggested that psychedelic narratives about women were somehow less important and less relevant than narratives about men. Morris’s film makes it clear that she is not merely a minor player in psychedelic history. Her self-published memoir and My Psychedelic Love Story speak to many people because they offer powerful narratives of redemption; she survived the wreckage of the 1970s and converted to Buddhism. In the last two decades of her life, she became a prolific podcaster, an activist for psychedelic healing, and a passionate critic of our nation’s inhumane drug policies. [3]

The last frame of the film reveals that Harcourt-Smith passed away on October 12, 2020, while surrounded by her husband, children, and grandchildren. Harcourt-Smith, who was 74 at the time of her death, learned that she had developed Stage IV breast cancer when My Psychedelic Love Story was being put together and edited. When the COVID-19 pandemic struck in early 2020, it looked like the film would probably not be completed in time for Harcourt-Smith to see it. I recently contacted Harcourt-Smith’s husband, José Luis Soler, and her daughter, Lara Tambacopoulou, to see if Joanna had a chance to see the film before she died; both told me that Joanna was able to see the completed film just three weeks before she died. They reported that she adored the film and watched it many times. She was at peace because she died knowing that her story was finally being told.

¤

James Penner is the editor of Timothy Leary: The Harvard Years (2014) and the author of Pinks, Pansies, and Punks: The Rhetoric of Masculinity in American Literary Culture (2011).

¤

[1] The leaders of the WU who facilitated Leary’s escape from the California Men’s Colony were never actually caught by the FBI.

[2] In 1970, Leary was given a 10-year sentence for possessing a few grams of marijuana. In 1973, he was given a 25-year sentence for marijuana possession and for escaping from the California Men’s Colony in San Luis Obispo. Since Leary was 52 when he was convicted, he would be 77 when released, according to John Bryan’s Whatever Happened to Timothy Leary? (1980).

[3] At the time of her death, Harcourt-Smith and her partner José Luis Gómez Soler had interviewed over 400 subjects for their podcast, Future Primitive (see https://futureprimitive.org/).

LARB Contributor

James Penner is the editor of Timothy Leary: The Harvard Years (2014) and the author of Pinks, Pansies, and Punks: The Rhetoric of Masculinity in American Literary Culture (2011).

LARB Staff Recommendations

Toward a Saner Psychedelia

Ido Hartogsohn’s new book explores the impact of LSD on postwar American society and culture.

“Retreat” and the Sick World

Madeline Lane-McKinley reviews "Retreat: How the Counterculture Invented Wellness," the recently published book by Matthew Ingram.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!