The Body in Topography

Mariam Gomaa reflects on the intertwining characteristics of health, surgery, religion, and philosophy.

By Mariam GomaaNovember 27, 2022

IN ONE OF my earliest memories, I am standing outside my brother’s bedroom. A firefighter walks past, stepping on my right foot with his large heavy boot. I am five or six years old, and my brother is two or three. It may be summer, but I can’t be sure. The power has gone out in our Upstate New York neighborhood. Outside, our neighbors stand and watch the fire truck pull up to our home and the firefighters carefully install a generator into our little townhouse in order to keep my brother’s ventilator working overnight despite the power outage.

My brother is an unusual medical case; he was born with numerous disabilities and survived meningitis with severe brain damage. I became a physician because of him, and in medical school, I unraveled his illness one lecture at a time. I learned about his physical disabilities in anatomy, examining cadaver joints and organs. In neurology and pulmonology, I learned about his breathing problems, and in the cardiac ICU, I learned how to put it all together to understand the reasons his heart kept failing him.

On Saturdays, growing up, we would spend the day in silence, speaking only in sign language to improve our skills and communicate with him. I would often grow frustrated learning this new language, but would become more frustrated with myself for not grasping the entirety of his illness. I wanted to know what my brother thought every day of his life that felt so different and yet so similar to my own. How was it that we existed, living parallel yet radically different lives, made so by mere consequence of the body? The body — that thing not chosen, but given to us, and to which we ultimately must adapt.

I am, in truth, obsessed with the body, which is, all at once, so mysterious and so plain. As a Muslim, I was raised with the idea that the human form is made from clay, dust, earth — a smattering of words each meaning, at their core, dirt. And at the heart of this meaning, the body itself, considered sacred, is somehow, too, debased by its sheer worldliness.

When you open a body, it’s largely the same, neat and organized in a predictable way. Yet vast differences exist among us, in personhood, in appearance, in pathology. A tumor, for example, can change the sanctity of our similitude.

My brother’s body reflects the rare genetic syndrome he was born with: fusion of the cervical spine, a solitary kidney, short stature, a flat occiput, missing cochlea. His body, though nontraditional in its makeup, is functional. Medicine, in all its physiologic intricacy, is largely formulaic, and has thus left his medical anomalies solvable. But medicine is not benign, and for all our understanding of what composes a human being, physicians make mistakes. I try not to fault the doctors who didn’t recognize the postoperative infection in his brain, try to remember that every intervention is not without consequence, but it’s hard to have empathy. I wonder what our relationship might be like if someone caught the illness early, how much they might have changed his life, and mine, without ever knowing.

The first time I made an incision during surgery, I was a third-year medical student scrubbed into a kidney transplant. I carefully cut the skin and opened the abdomen down to the peritoneum, smooth as saran wrap around the organs. I wanted to touch every one of them.

Over the past year, my brother’s solitary kidney has been failing. His name sits on a national transplant list. For years, Islamic theologians have debated the moral indications of organ donation. They wondered if removing organs could be considered a desecration of the body, which must ultimately return wholly to the earth, deteriorating to dust in its original form, in order for the soul to ascend to heaven. In recent years, clerics have declared it permissible, some going as far as deeming it sadaqah jariyah (eternal alms). What was once discouraged, the act of permanently altering the physical self, was now made holy by saving another.

I want to give my brother one of my kidneys. My mother opposes the idea. There is much at stake, spiritually, logistically, emotionally. Her own sister had two kidney transplants in her lifetime, a consequence of a long and complicated illness. She is afraid. I think I can understand. But part of me knows something she doesn’t, the intricacies of the surgery: the retrieval of the kidney from one body, the way the new kidney is seated in the pelvis of its recipient, and the flush it gains when blood reenters it. The calculated precision of the body, even in the ways it fails, is reassuring.

I think often about my own body and the story it tells. Like my brother’s, my body is syndromic. The word “syndrome” itself refers to a constellation of features that appear together, and when correlated with each other are assigned to a particular disorder. Mine, too, is rare, but relatively benign — a syndrome in which the lateral mobility of my left eye is limited due to a failure of neuronal migration. The syndrome itself has been studied and thought to relate to specific gene mutations, although it is rarely inherited. Incidentally, some individuals with my brother’s syndrome may also have mine. I’ve spent hours scouring the National Institute of Health’s Genetic and Rare Diseases database. The genetic correlation between our syndromes is unestablished. In fact, both these syndromes often occur as spontaneous mutations and are rarely inherited.

It seems like a strange stroke of fate for two of my parents’ four children to have rare genetic syndromes. But lightning does strike twice, far more than we know, and maybe it is just random chance that our genomes have deviated from the conventional. More than anything, it feels like our fates are tied together, like one snippet of genetic code could have changed our destiny such that we would live the lives of each other.

There are six antigens known to be most important to tissue typing for organ transplantation. We inherit three from each of our parents. It is rare to have a perfect six antigen match between two people, unless they are siblings, or better, identical twins. The body makes antibodies against another person’s antigens, which, if strong, will lead to rejection of the implanted organ. The better the match, the lesser the chance of rejection.

On average, a kidney transplant lasts about 10 years, sometimes more, sometimes less. If a kidney is unavailable, the person remains on the transplant list while undergoing dialysis, their entire blood volume extracted and purified through a machine 100 times the size of a kidney doing the work of the tiny organ. Recently, the Supreme Court ruled that insurance companies can limit a patient’s access to dialysis sessions despite physician recommendations, relegating patients to the sequelae of their deteriorating organs.

When the kidney fails, there are distinct metabolic abnormalities. Electrolytes become imbalanced, the body becomes acidotic, and nitrogenous waste compounds accumulate. The resulting uremia eventually leads to a number of end organ manifestations, including the decline of the central nervous system. One of my professors in medical school described dying from end-stage renal disease as much like falling asleep.

In Islamic theology, the soul (rūḥ) is separate from the ego (nafs). The ego itself is earthly in nature, associated with the body. The ego is divided into three parts defined by desire; the first for what is base and low and wrong; the last for what is divine and right and good. The part of ego that lives between is the one that desires both and lives in reproach of the self for transgression. Existence itself becomes synonymous with the challenges of the nafs; to have a firm grasp over one’s desire is to achieve serenity.

The nafs is constantly at odds with itself. Some days I understand my desire to give my kidney as a way to reconcile the thread of genetic code separating my life as a physician from my brother’s life as a patient — this eternal alms bringing our fates into a single line. Simultaneously, I understand my acceptance of my mother’s fear as a reflection of my own. Despite what knowledge I may have, I know physicians are fallible, myself among them. My ego remains imbalanced in one direction or another on any given day. My hubris meets fear and devotion. The nafs of love for the divine with the nafs immersed in this corporeal world: I am left wondering which is a reflection of the other.

Last week in surgery, I rested my fingers on a woman’s aorta, her heartbeat thrumming beneath my fingers, her entire blood supply passing by as we removed a tumor. She was under anesthesia, somewhere between the world of the living and the dead as my hand was resting inside her body — a fact she will never know or remember.

For all my understanding of the body, nothing about medicine or science has explained the abstract part of our being which defines the self, the very nature of being alive. Chemically, biologically, we can dissect every part of the human body and explain its mechanisms to the core. Spiritually, we all believe different things about how we come to exist in the universe. In truth, I don’t know that it matters if we are certain in our knowledge of either. At the end of the day, we live as best we can until we become obsolete.

I have thought often about the life my brother has lived thus far, and how the end of it might look. As a doctor, I know how I would want to die, at home with the people I love, with as minimal medical intervention as possible. Despite our family conversations about his health, death remains unfathomable. The thought devastates me.

And yet, Islam offers us eternal life, beyond the confines of this body. Because I am human, my ego questions my faith and the nafs collapses on itself in varying shades. But I never wonder if there is a next. I have to believe it. In that realm, my brother’s spirit can exist without limits. In that world, he is free from the tribulations of the body that fails him. We can meet, in our metaphysical forms, without the dynamic of dependency between us, as equals.

In some small way, the thought of giving my organ feels like a tangible manifestation of love for my brother, who has shared a lifetime alongside me, and for my mother, who was our first bodily home. A part of myself would always be with him, at least on this earth. Does that make it more or less divine?

On the phone with my mother recently, I ask if she remembers that night in New York many years ago. She reminds me that there was not one, but many, and somehow we can laugh at the peculiar ordinariness of it — how when the firefighters finished their work and trudged down the stairs, I turned back to the room I shared with my sister. I flicked the light switch and looked from the window into the street at our gaping neighbors, all astounded by the curious events that had become normal for our family. The hum of his ventilator echoed through the night. Someone waved. I waved back from my perch in the window as our house shone in the darkness.

¤

¤

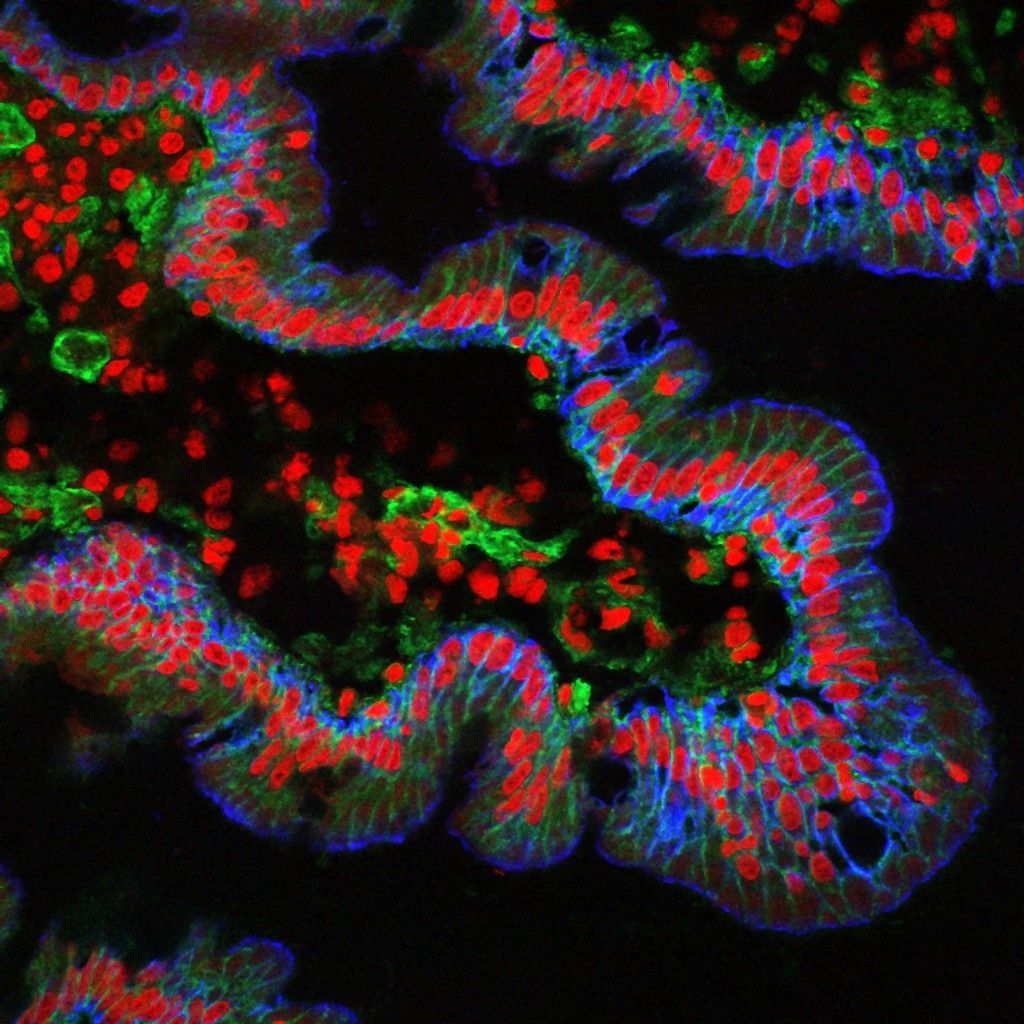

Featured image: S. Schuller. Villi from the Small Intestine. Wellcome Collection. wellcomecollection.org, CC BY 4.0. Accessed October 21, 2022.

LARB Contributor

Dr. Mariam Gomaa is a physician and writer based in Washington, DC. She is the author of Between the Shadow & the Soul. Her writing has appeared in Time, NBC News, Rhino Poetry, Mizna, Nimrod International Journal, and Readings for Diversity and Social Justice (Fourth Edition), among other publications. She loves Octobers, the smell of palo santo, and meaningful conversations on a rainy day.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Between Love and Envy

Jody Keisner explores love and envy between sisters in and outside her family.

The Things We Carried to Chemo

Lisa Glatt explores first her mother’s and then her own experiences with cancer in the context of national politics and family life.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!