A Sane Man in a Demented Age: On Julian Barnes’s “The Man in the Red Coat”

Richard M. Cho appreciates "The Man in the Red Coat," the new biography of Samuel Jean Pozzi by Julian Barnes.

By Richard M. ChoFebruary 18, 2020

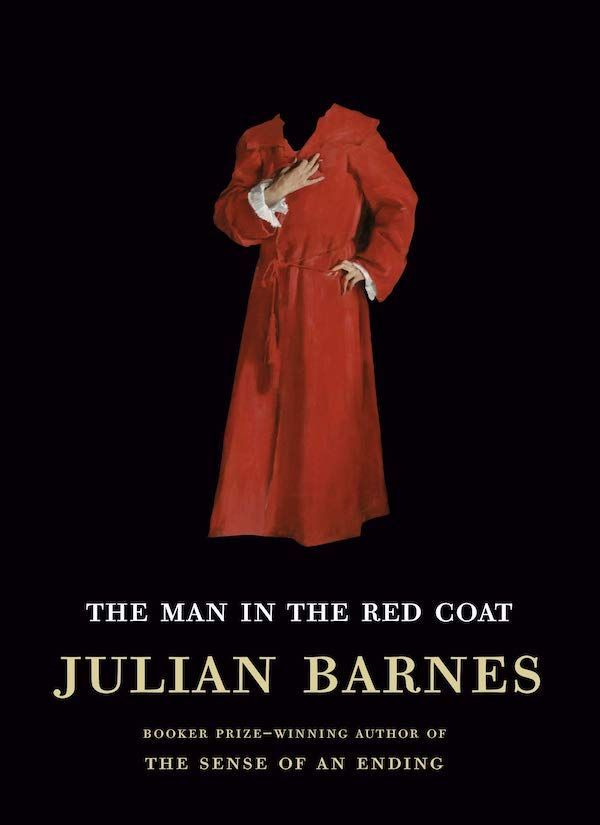

The Man in the Red Coat by Julian Barnes. Knopf. 288 pages.

THE HAMMER MUSEUM, located at the foothill of the Westwood Village in Los Angeles, has been home to a life-sized portrait of Dr. Samuel Jean Pozzi since 1990. Titled Dr. Pozzi at Home, it hangs regally inside the Armand Hammer Collection gallery on the third floor, occupying one whole side of a wall. Pozzi is primarily remembered as a pioneering surgeon and gynecologist in France during the time period retrospectively labeled as La Belle Époque.

The portrait was on loan in 2015, and it was then that an English novelist came across it in the National Portrait Gallery in London. Despite being a life-long Francophile, he was unfamiliar with its subject. According to the label, it was painted by the American artist John Singer Sargent back in 1881. Soon afterward, he read an article in an art magazine that described Pozzi as “not only the father of French gynecology but also a confirmed sex addict who routinely attempted to seduce his female patients.” The English novelist writes in his new book, “I was intrigued by such an apparent paradox: the doctor who helps women but also exploits them.”

That English novelist was Julian Barnes, the author of more than 20 books and arguably the most versatile writer alive. (He is often called a “trans-genre writer.”) When he encountered charismatic Pozzi dressed in all scarlet in the portrait, a muse descended upon him. Pledged to the ideal of producing a very different work each time, he has penned yet another truly innovative book that is like no other he has written before.

Barnes’s new book, The Man in the Red Coat, is ostensibly about Pozzi, but it readily challenges the tacit boundaries of conventional biography. Its panoramic gaze captures the vagaries of life, full of vanity and vainglory, during La Belle Époque. The French term is commonly translated as The Beautiful Era, and it’s fitting that a consummate ironist like Barnes has chosen to write about this specific period. Despite its uplifting name, the period resembled the “frenetic, rancorous, bitchy nature of the age,” its titular beauty borne out merely in context of the hideous destruction wrought by the two subsequent great wars. Full of meta-commentary on what writers risk when reconstructing the past, the book seamlessly weaves the stories of numerous personas navigating the demands and fashions of fin de siècle France.

Throughout his 30-year-plus writing career, Barnes has published a number of fictional biography, notable among them Flaubert’s Parrot (on Gustave Flaubert) and The Noise of Time (on Dmitri Shostakovich). During an interview with the London Review of Books back in 1982, he said: “The traditional, academic approach to biography — the search for documentation, the sifting of evidence, the balancing of contradictory opinions, the cautious hypothesis, the modestly tentative conclusion — has run itself into the ground; the method has calcified.” To this dilemma, he had devised a solution by introducing the elements of fiction in his account of historical figures. “Fiction, more than any other written form, explains and expands life.”

In his new book, however, he conspicuously withholds any fictional imagination from the narrative. The most repeated phrase throughout the book is “I cannot know,” as Barnes acknowledges that it is a powerful phrase when used sparingly in a biography. There is even a section preceded by the heading “Things We Cannot Know,” under which Barnes enumerates all the things impossible to know about Pozzi’s life. Then, he wryly comments, “All these matters could, of course, be solved in a novel,” while holding himself back from such indulgence. Even when he is delivering a seeming fact or a recorded dialogue, he cautions us if the information is derived from a single source. No gaps are filled with his usual novelistic prowess. What compelled this change in method for Barnes this time? Also, why write about Pozzi when a comprehensive biography, written by Claude Vanderpooten in 1992, already exists?

¤

Pozzi was called many things during his life: he was “a doctor, a public figure, a senator, a village mayor, a campaigner, a scientific atheist, a public Dreyfusard, and a Don Juan.” He is indeed known for his numerous romantic liaisons with some famous female socialites of the time, most notably with Sarah Bernhardt, a renowned French stage actress at the time, who called him “Docteur Dieu (Doctor God).” In a letter to Henry James, John Singer Sargent referred Pozzi as “a very brilliant creature.” Alice the Princesse de Monaco exclaimed “disgustingly handsome” upon seeing him for the first time. Not only was he one of the most accomplished surgeons in Paris, but was also a founder of the study of gynecology in France. He wrote a two-volume set titled Traité de gynécologie clinique et opératoire (Treatise of Gynecology) that is over 1,100 pages long — the first of its kind in his country — and published more than 400 scientific papers during his lifetime. Amid all this, he found time to translate Charles Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Another frequently repeated phrase in the book is: “But Pozzi was everywhere.” One can’t help but harbor a suspicion that Pozzi must have had a doppelgänger (or two).

But as the art magazine declares: was he a sex addict as well?

¤

The book “prosaically” begins and ends with Sargent’s portrait of Pozzi. In fact, it initially hesitates, contemplating a number of other possible opening paragraphs (Three Frenchmen arriving in London, Oscar and Constance Wilde honeymooning, a gun firing a bullet, and more). This narrative indeterminacy foreshadows the historical indeterminacy innate in all biographical works, affirming that a writer’s whim profoundly affects the telling of the past. The narrative then hopscotches, mainly in order to jump over the gaps in historical sources, bouncing back and forth in time, latching here and there to draw and comment on figures and events, gossip and trends of the day, guided strictly by archival sources. Often, many pages pass by without a single mention of Pozzi. Infamous artists make prolonged appearances: Oscar Wilde, whose maxims are “sophistry posing as paradoxical wisdom”; Joris-Karl Huysmans, whose book À Rebours (Against Nature) was “a dreamily meditative bible of decadence”; Edmond de Goncourt, from whom no gossip was safe and whose journal entries appear frequently in long excerpts; and Robert de Montesquiou, a flamboyant homosexual and incorrigible dandy whose eccentricity is embodied in fictional characters created by Dumas, Huysmans, Proust, and many more. The book can be said to be just as much about Montesquiou as it is about Pozzi. It is truly eclectic in its telling, full of pithy aphorisms and ardor.

Another formal technique newly taken by Barnes this time reaffirms its archival characteristic: the use of black-and-white photographs and paintings of the day. We are tempted to compare his new book to those of the great German writer W. G. Sebald, whose incorporation of photographs within the narrative had been superbly effective. For every person that Barnes’s narrative even skirts around, a cigarette card-sized headshot of that person appears on the page. Roland Barthes once wrote, in his signature book Camera Lucida, “Perhaps we have an invincible resistance to believe in the past, in History, except in the form of myth. The Photograph […] puts an end to this resistance.” Barnes’s formal choice seems to be urging us to distinguish myth from History, fake news from fact, and rushed, condescending misjudgment from rational analysis.

The book is especially strong and entertaining when it portrays the idiosyncrasies of the age, such as the duel (Pozzi was never involved in one whereas Jean Lorrain, Daudet, and Proust were all participants of this absurd way to settle volcanic egos) and dandyism (its motto: thought is of less value than vision). Barnes allows the concepts and fashions of the era to be defined by the written records of what people had said about them, presenting readers with the opportunities to observe through direct account, as though we are observing archival materials firsthand.

Although the book reconstructs the time period more than a century ago, it attracts a parallel comparison with the current political state of England and the United States. La Belle Époque was an era that witnessed “a rise of blood-and-soil nativism,” to which the Dreyfus Affair was a testimony. Conservatives blamed Jews, homosexuals, and effete males for the decline of the European race. At the moment, both England and the United States are suffering from the rise of nationalism. In the author’s note at the end of the book, Barnes professes that Pozzi’s maxim, “Chauvinism is one of the forms of ignorance,” came frequently to his mind as he witnessed the Brexit campaign and the United Kingdom voting to leave the European Union in a referendum called by David Cameron.

What gives Barnes hope is that even during the era described as “decadent, hectic, violent, narcissistic, and neurotic,” there lived a person who was “rational, scientific, progressive, international and constantly inquisitive; who greeted each new day with enthusiasm and curiosity; who filled his life with medicine, art, books, travel, society, politics and as much sex as possible (though all we cannot know).” Pozzi was an ardent Dreyfusard, the first to come to his aid when Dreyfus was shot at Emile Zola’s exhumation. Barnes draws the conclusion that Pozzi is a hero. But was he also a sex addict? Barnes answers: “Pozzi never emerges from documents of the time as the kind of ruthless libertine — indeed, ‘sex addict’ — into which he is being transformed by a twenty-first-century coarsening of language and memory.” Is he hoping to rectify the wrongly remembered past by writing a book drawn wholly with evidential narrative?

Barnes’s writing, once again, is clear, erudite, and deeply insightful. Reading his prose reminds one of what Nabokov once said: “The highest virtue of a writer, of any artist, is to stimulate in others an inward thrill.” Barnes is, without a question, that kind of writer, whose wit, intellect, and pleasant irony incite a lasting thrill in us.

So, Pozzi continues to greet visitors at the Hammer Museum. He looks on, reminding us that, like him, we should strive to remain sane and rational however demented this world may seem at any given moment.

¤

LARB Contributor

Richard M. Cho is a research librarian for Humanities and Literature at University of California, Irvine. His writing has been published in Tint Journal, Asymptote, LA Review of Books, and more. He is the founder of the book and movie review website, www.jjjreview.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Annotations of Pain: First Love in “The Only Story”

Thomas J. Millay finds Julian Barnes’s “The Only Story” a perplexing, profoundly enjoyable story about the phenomenology of love.

Irony: Truth’s Disguise

Irony states the opposite of what it intends to mean. But what if no one spots it and takes the ironic statement literally?

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!