A Hymn to Life: On “Shatila Stories”

Isaac Nowell relishes “Shatila Stories,” a “hymn to life” written in the Shatila refugee camp in southern Beirut.

By Isaac NowellMarch 21, 2019

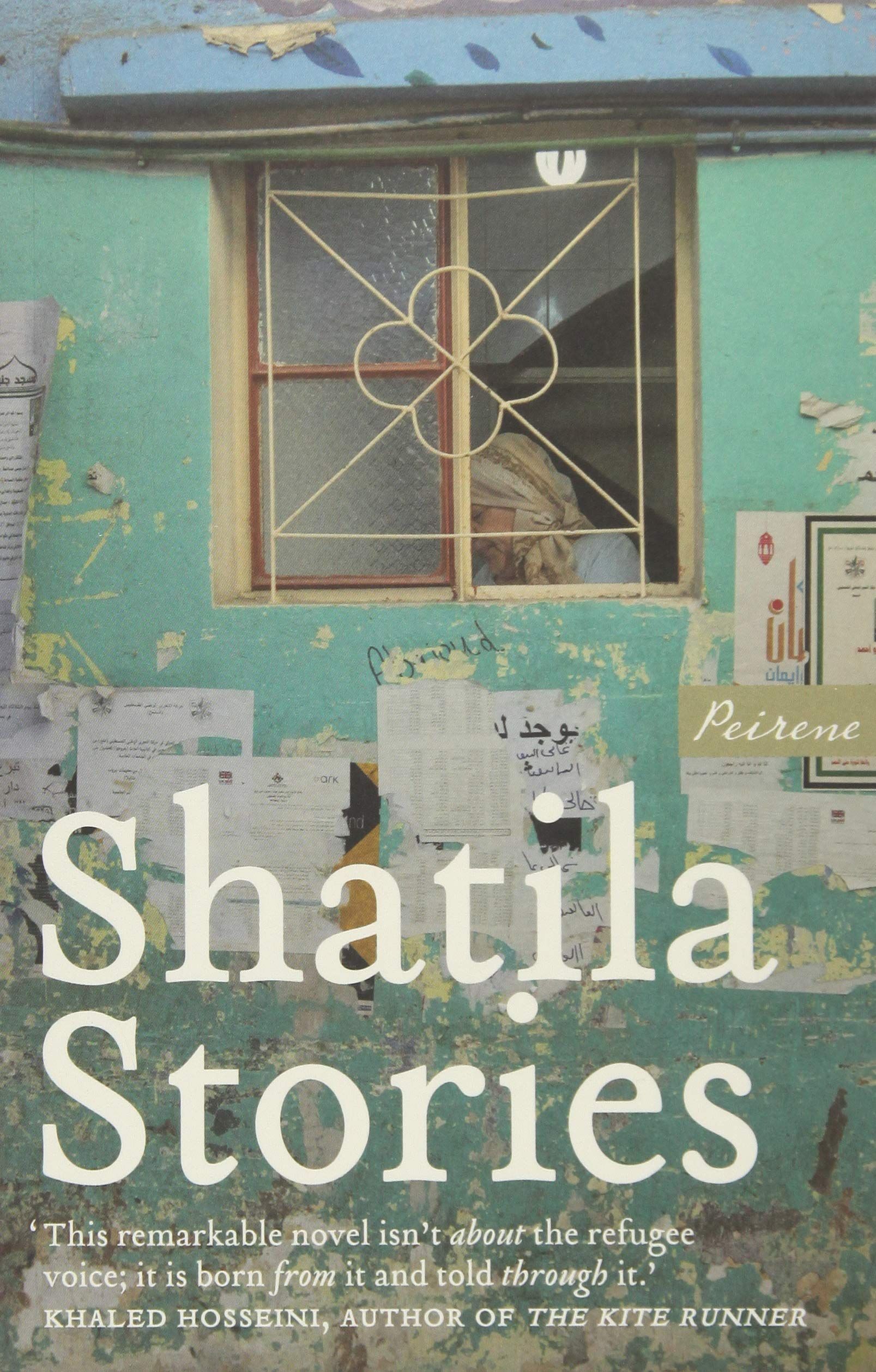

Shatila Stories

Buy Shatila Stories from the Peirene Press website. All sales go to support refugees.

¤

THE SHATILA REFUGEE CAMP in southern Beirut, Lebanon, is probably most famous as one of the sites of the Sabra and Shatila massacre. On September 16, 1982, at approximately 6:00 p.m., a militia close to the predominantly Christian Lebanese right-wing Kataeb Party — also named Phalange — began carrying out a two-day massacre in the Sabra neighborhood and adjacent Shatila camp, killing between 460 and 3,500 civilians. The Phalanges, allies to the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), had been ordered to clear out the Palestine Liberation Organization’s (PLO) fighters from Sabra and Shatila, as the IDF sought to maneuver into West Beirut.

By the time of the massacre, the camp had existed for over three decades. At the end of the 1947–1949 Palestine War — known in Hebrew as the War of Independence and in Arabic as al-Nakba, or the Catastrophe — the State of Israel claimed not only the area recommended by the 1947 United Nations partition plan for Palestine (General Assembly Resolution 181 [II]), but also nearly 60 percent of the area allocated to the proposed Arab state, including the Jaffa, Lydda, and Ramle area, Halilee, parts of the Negev, a strip along the Tel Aviv–Jerusalem road, and some territories in the West Bank, placing these lands under military rule. The Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan (later Jordan) claimed the remainder of the West Bank, which it annexed; the Egyptian military took the Gaza Strip. With Jordan occupying the West Bank and Egypt occupying Gaza, no state was created for the Palestinian Arabs. Around 700,000 of them fled or were expelled. Displaced, many sought refuge in the north, in Lebanon.

The Shatila camp was established in the southern suburbs of Beirut in 1949 by the International Committee of the Red Cross to house the hundreds of refugees pouring into the area from northern Palestine. In the wake of the Syrian Civil War, which erupted in 2011, Lebanon’s population increased by more than one million, and Shatila, according to a 2014 survey by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East, has swollen from an intended capacity of 3,000 to up to 22,000. The population has continued to grow, and in her introduction to Shatila Stories, Meike Ziervogel puts it at up to 40,000.

With the history of the atrocities bridging the Palestine War and the ongoing Syrian conflict in mind — as well as the stories and images of unimaginable suffering and inhumanity that meet us each day in the media — one might justifiably expect Shatila Stories to offer a detailed account of war, displacement, pain, and death. This is not what you will find. More precisely, while these things necessarily exist in the landscape of the book — lurking in the shadows and on the fringes, at times reasserting their presences — they are neither its focus nor its motive. As Ziervogel explains in her introduction:

I was clear in my mind that I didn’t want flight stories from the writers. These have been covered enough by our media. I wanted to address something else, something that comes from my experience as a writer of stories: the power of collaborative imagination to open up new ways of remembering and from that, perhaps, a vision for the future.

Shatila Stories is also not a “poor-refugee-can-also-write kind of book,” as Meike Ziervogel also feared it might be interpreted. Instead, the genesis, conception, and realization of the book testify to the powers of collaborative imagination. Ziervogel, the founder and director of London-based Peirene Press, which specializes in first translations of European novellas into English, reached out at the beginning of 2017 to the Lebanon-based charity Basmeh & Zeitooneh (which translates as “the smile and the olive”). The nongovernmental organization runs community centers in a number of refugee camps, including Shatila. “I wanted to find a group of Syrian writers,” she writes, “teach them the principles of storytelling and then publish a book of their work.” Suhir Helal, the Syrian editor of the book, similarly insists:

We normalised their lives instead of treating them as victims. We did not go there to deliver aid, money or food. We went there to deliver a unique workshop that touches the hidden aspect of our existence; the creativity and imagination of a human being.

Ziervogel arrived in Shatila in July 2017, accompanied by the London-based Helal. In the meantime, Basmeh & Zeitooneh had run a preselection workshop and sent them 20 short writing samples. Still, as might be expected, the project was anything but straightforward. “Suhir and I didn’t choose the best extracts. That was not an option,” explains Ziervogel. “We chose the nine least bad.” It was of course not simply that most of the participants “struggled to write proper Arabic and organize their thoughts” — many of the authors had never completed school and some had never read a novel — but that, over the course of the workshop,

the writers dealt with many challenges: mainly illnesses due to the atrocious hygiene in the overcrowded camp, but also the sudden deaths of family members. One participant’s niece was killed by the low-hanging electrical cables, a grandmother slipped badly in one of the camp’s muddy alleys and someone else’s father died in Syria.

After hitting rock bottom and scolding themselves for being so naïve as to undertake the project, toward the end of the third day, Ziervogel recalls, something changed: the authors became focused and determined. “I’ve needed this opportunity for such a long time,” said Omar Khaled Ahmad, one of the co-authors. “I had a lot of thoughts to write down but I didn’t know how to direct and express them. I have now learned how to organize my thoughts and I’m so happy to write the story.” In October 2017, Ziervogel and Helal returned to Shatila and sat down with each of the nine writers individually, in order to bring out the strengths in the stories and finish them. Afterward, Nashwa Gowanlock translated everything into English.

Whatever other admirable effects it may have had — a powerful exercise in art therapy, a continuing donation to a relevant charity (£0.50 for each book sold goes to Basmeh & Zeitooneh) — the novella is a remarkable work of art in its own right. Remarkable not only as a rare, if not unique, instance of collaboration between publisher, translator, editor, and nine co-authors, but also as a structurally innovative contribution to the genre of narrative prose fiction. “We received four good stories and five interesting drafts,” the introduction explains, which suggests a collection of nine stories by each individual author, but the piece is something much more cohesive and holistic: a fluid, continuous piece of prose with no visible seams, breaks, or awkward transitions.

Hiba Marei, the author of the opening chapter, describes a chaotic scene at the Syrian-Lebanese border that resembles her own experience. (A Palestinian-Syrian born in the Yarmouk refugee camp in Damascus, Syria, Marei and her family fled in December 2012 after the camp suffered an air strike by Syrian government forces.) Our central character’s name is Reham. Traveling by car across the border, images of “shooting and shouting and panic and fear and blood” flicker through her mind before she finally succumbs to sleep. When Reham arrives at Shatila, she and her family meet Muneef, a boy living in the camp, who guides them toward the apartment that would become their new home. She spots graffiti on a wall that Muneef proudly declares he had freshly painted that morning, which reads, “Don’t talk about the camp unless you know it.”

The first two chapters are written from Reham’s perspective and give an account of her life before her family’s flight from Syria. This centers on her marriage to Marwan, and its repercussions: “That’s the way for women in our culture: we spend our whole lives forgiving and getting nothing in return.” Reham’s story is her fight for independence, her discovery of her own strength and identity. It is also the story of women all over the world, of cultures past, present, and, no doubt, to come.

Each chapter is sensitively written and emotionally compelling, but equally compelling are the shifts in perspective between chapters. In the opening chapters we experience the camp from Reham’s point of view, but we are also introduced to Adam, her young brother. Later, we will see the world through Adam’s eyes and learn of his love for a young woman who has grown up in Shatila, Shatha. Later yet, we focus on Shatha, her family, and the complexity of her relationship with the camp: “I tell him how I feel deeply conflicted when it comes to the camp. That I both love and despise it, that it bores me yet I long for it, how I reject it and desire it.” In another chapter, Jafra, a young girl, is “named after the martyred hero […] killed in an Israeli air strike over Beirut in 1976, […] a national icon,” and in another we meet Youssef, a kind of Mafioso in the camp (which the Lebanese police refuse to enter), as he threatens a young man for not paying his electricity bill. It then turns out that this same young man, Ahmad, is the alcoholic father of Jafra. And so on. By the end, we’ve experienced a symphony of perspectives on life in the Shatila camp. The psychological proximity of each character to the other, the fact that there is no such thing as a minor character in this book, reflects the claustrophobia of the setting, with its narrow, bricolage alleys, its threatening, low-hanging electrical cables that crosshatch the sky, and some 22,000 human beings living in a space built for 3,000.

While Shatila Stories is an excellent work of narrative prose fiction, and ought to be measured and valued as such, it’s also politically charged. The poem that prefaces the book demands: “Spare us your good intentions, your quiet pity. / Instead, look up and raise your fist at the sky.” And the stories the book contains ask readers not only to bear witness, but also to consider their own responsibility. “One of the worst things that can happen to a person is to be forced to live without goals,” reflects Shatha, considering her own and others’ existence in the camp, “[a]nd the sign of ultimate failure is for them to live two identical days. As for me, my life is the epitome of failure.” But it is not her failure, because her life is circumscribed by forces beyond her control. “[A]ll of them,” she continues, “boys and girls, men and women — bear the same wounds. Born bearing the burden of the Palestinian cause into a country which refuses to accept them as citizens, keeping them as refugees, as outcasts, they have grown up suffering.” Here I was reminded of Hannah Arendt’s assessment of human rights: “The fundamental deprivation of human rights is manifested first and above all in the deprivation of a place in the world which makes opinions significant and actions effective.” How relevant these words have remained. Shatila Stories is a hymn to life in adverse conditions, but it is also a call for change, and this too must be acknowledged. “When I embarked on this project,” reflects Ziervogel in the introductory pages,

I had the idea that by pooling our imaginations we might be able to access something that would transcend the boundaries that surround individuals, nations and entire cultures. In the face of human catastrophes such as the Syrian refugee crisis, I wanted to see if it was possible to alter our thinking and so effect change.

Together, the authors, editors, translator, and coordinators have achieved the first of these goals. The second is left up to us.

¤

Isaac Nowell is a writer who lives in Cornwall, United Kingdom.

LARB Contributor

Isaac Nowell completed his masters on 20th-century literature at the University of St Andrews, specializing in the poetry of W. H. Auden. He currently lives in Cornwall, United Kingdom.

LARB Staff Recommendations

What Is Good in Man Is Love: An Interview with Elias Khoury

A lion of Lebanese literature reflects on art, religion, memory, and pain.

A Sidelined People: On the Crisis in Palestine

Two new books examine the consequences of the failed bid for Palestinian statehood.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!