A Galaxy of Monuments

Jill Schary Robinson visits “City of Immortals: Père-Lachaise Cemetery, Paris,” the recently published book by Carolyn Campbell.

By Jill Schary RobinsonJanuary 15, 2021

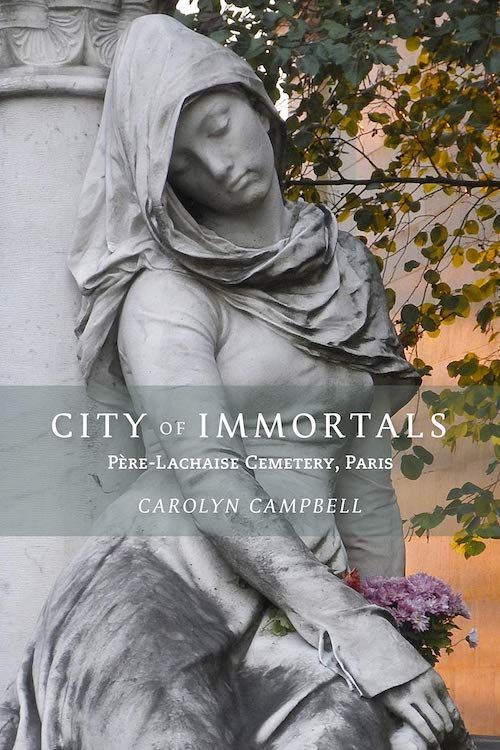

City of Immortals by Carolyn Campbell. GOFF BOOKS. 200 pages.

IN THE BEGINNING of her extraordinary book, City of Immortals: Père-Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, Carolyn Campbell tells us of her father’s urgent message as he was dying: “Carolyn, never put off your dreams.” “He never realized his own dreams,” she says, “of being a writer.” Carolyn, however, has realized this dream and, indeed, has given her father’s soul a place among the iconic artists in Père-Lachaise, the glorious cemetery in Paris, founded by Napoleon Bonaparte.

In our culture, death, in a sense the goal of life’s journey, is rarely given the dignity and grace it deserves. Carolyn was first introduced to this ultimate transition when she watched her grandfather’s casket carried by a horse-drawn caisson to his funeral at Arlington National Cemetery. There were gold braided epaulettes on the soldiers’ dark blue uniforms, and shiny swords. She watched the precision as they folded the flag, the posture of honor as the bugler played taps.

A lamp might well have been lit at this first funeral, for Carolyn studied under a Buddhist teacher: “[H]is practice focused on being in the present, but then he asked that I sit with the question: ‘I am going to die; how do you feel about that?’” “Understanding,” she explains, “goes deeper the more fully you relate to death. You become clearer about what is important and what is not, the more you accept death, the more you embrace life.”

City of Immortals is as much a photographic tour of Père-Lachaise as it is a memoir of Carolyn’s own artistic evolution. The celebration of the cemetery includes captivating conversations with the legendary spirits residing here. Authentic voices welcome her gift, reminding us of their stories; like an accomplished curator, she leads us through the galaxy of artists’ monuments, tombs, and sculptures: an enthralling network of paths, a woodland of symbolic images, tributes meaningful to each resident, garlanded by courteous vines, trees, brush, flowers.

The figures are nestled, perhaps leaning against the trunk of a tree, seasons of bark edited by storms. Ghosts study here, translating the musing of leaves. The slim traffic of wings and paws crisps through buds and bristles, telling stories from the other side of Beyond. With this treasure, our private fears of death avoid the bolts of despair. If I could lie and say I was born in Paris, I might be buried here when the time comes. This buoyant home where wi-fi has placed no roots, where inhabitants are cherished for their gifts to their grateful cultures.

Carolyn’s favorite season, autumn, glows here through the galleries of photographs, most taken by her but some provided by the splendid English photographer Joe Cornish. You enter a towering arcade of trees, like fans, leaves golden, topaz, sienna, and honeyed gray fluttering from the dark chocolate tree trunks. No one describes the sounds better than Carolyn:

Overhead, the trees form a latticed canopy. Occasionally, a brilliant beam will break through and spotlight a tomb, dust motes dancing in the filtered sunbeams. I hear the rat-a-tat of woodpeckers, the trill of the nightingale, the cooing of doves. Crows caw mournfully as they swoop low over the mausoleums. Feral cats squint into the midday sun from the crypt-top perches. Tree roots and vines aggressively embrace headstones and sometimes unseat them. A tree trunk has become one with a small chapel, at first strangling it, yet now oddly supporting it.

Photographs of the arbors, trees, symbols, and tombs capture the subtle sensual tones of Michelangelo, da Vinci. We are surely in another century, not the “past” we miss today.

Throughout the tour of the paths, Carolyn stops and summons the “residents” into exchanges where their spirits rise, stretch, and reveal their tragedies and lusty secrets. Like a maître d’ at a cherished restaurant, Carolyn leads us through, acknowledging the most revered guests. These visits are like reading an artful storyteller’s menu: each resident rises into a delicious conversation, saucy even when filled with sorrow, one of Talent’s favored cloaks. We pass now by the curved marble staircase leading to the second-tier memorial for Isadora Duncan, who was born in California. You catch the background music, her Shalimar fragrance, as she stepped into the open sports car with the young mechanic, who recklessly sped off; her long chiffon scarf tangled in the spokes of the rear wheel, breaking her neck. Thousands of people attended her memorial service.

You will meet people you only knew from their books, their music, their position in galleries and museums. Here we can stroke a bare cool shoulder, leave a flower by an alluring sculptured knee. We learn far more original details about people we once talked about at dinner parties following art openings, concerts of musicians we’d studied (or said we did) or listened to, long ago. While many of the artists, poets, and musicians of the Romantic Age are buried here, we also meet Jim Morrison, the American wizard who created The Doors. Here is the great Colette on what she called her Raft, a wide, rose-colored marble platform, graced with plants and trees; there is an urn with a pink primrose, sitting in a boa of gray brush, rather like a starched collar. Carolyn isn’t shy with Colette: she asks the difficult questions about her parents, the restrictions she suffered for the freedom to write. From many of these phantoms, we learn how artistic dream overwhelms the body, in order to maintain talent’s own priority.

The stories fade into the stunning images of Oscar Wilde’s tomb, the proud Sphinx with a tawny stone helmet. There’s a fresh coral daisy perched on a ledge, a gift from a visitor:

Carolyn Campbell: Mr. Wilde, your tomb is one of the most visited in Père-Lachaise. Why do you think that is?

Oscar Wilde: Well, I am very flattered to see the throngs of handsome young men; I would like to think it’s because of my literary genius, but I understand it’s more about my being seen as a champion of gay rights. Ironically, I lived during what was called the gay nineties (1890s that is), but it had a totally different connotation.

CC: Your grandson Merlin Holland wanted people to know that you were more than a rare wit quick with a bon mot, someone who today might even be a talk show host.

OW: My fellow Irishman George Bernard Shaw said that I was “incomparably the greatest talker of my time — perhaps of all time.” So maybe there is something to what Merlin suggests; perhaps we might have a talk show where I could discuss with my guests the importance of creativity. I’ve always said, “Art should never try to be popular. The public should try to make itself artistic.”

CC: Honestly, I couldn’t fathom why you didn’t flee England for France when your friends begged you to. You would have escaped your trial and sentencing for your affair with the Marquis of Queensberry’s son, Bosie Douglas.

[…]

OW: I have never been concerned with people’s fear or prejudices. […] What is important today is that my monument is a place of pilgrimage for people from all strata of society. I appreciate the flowers and letters left for me, addressed to “the martyred poet.” […]

CC: Mr. Wilde, I deeply regret that in some aspects not much has changed in the hundred years since you passed. Though some countries now recognize same-sex marriage, others have called for gay people to face life imprisonment or, in some cases, execution if they are convicted of being homosexual.

OW: “The evolution of man is slow. The Injustice of man is great.”

Carolyn tells us early on that she was in love with Oscar Wilde. She didn’t have to say — we know that, for artistic women, the most alluring lovers are often bisexual. The ideal lover needs the transformation of mystique, deep imagination, winsome charm, a touch of wit, and the patience of the excellent artist.

Throughout the book, Carolyn’s prose catches the senses. If you listen carefully, you’ll hear footsteps on leaves, like walking on tossed-off taffeta robes; you hear a violin, catch the steely gleam of a sword, and bolt as it glides. Shadows give mobility to lounging lavender stone figures. The spirit of sensuality enjoys the company of these engaging works of art. Of course, artists always knew Paris was the place to be. You won’t be alone on this visit, however, for in the back of every copy of Carolyn’s book is a beautiful map with directions to each artist’s resting place. The map is placed in its own triangular pocket, to be unfolded with each turn, to reveal who might be where. You might make a bow to Marcel Proust, up in 85, across the Avenue from Isadora Duncan.

Imagine if one could restore faith in the notion of the permanent soul. City of Immortals gives death its proper forum. Our fear of death is that we shall be forgotten. Here, one’s gifts will be honored forever. Reading this book is like walking through this City of Immortals. I slowed down and took each image and conversation as a new way to consider eternity.

¤

LARB Contributor

Jill Schary Robinson has written for The New York Times, Vanity Fair, and The Washington Post. She is the author of Bed/Time/Story (Random House, 1974) and Perdido (Knopf, 1978). She has a lifetime grant to coach writer’s workshops, originally in London and now in Los Angeles.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Rapt Rereadings

Viv Groskop’s new book is a passionate love letter to the classics of French literature.

The Wilde Woman and the Sunflower Apostle: Oscar Wilde in the United States

Victoria Dailey looks back at Oscar Wilde’s wild ride through the United States in the early 1880s.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!