Iran’s “Master Poet of Freedom”: On Ahmad Shamlou

Niloufar Talebi reflects on the towering legacy of Iranian poet Ahmad Shamlou on the anniversary of his birth.

By Niloufar TalebiDecember 12, 2022

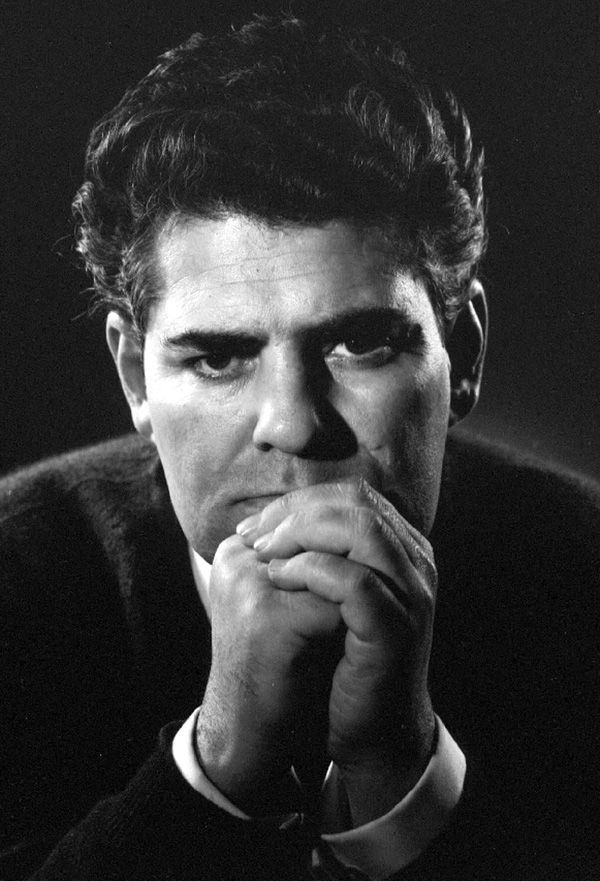

So much yet so little has changed in Iran since December 12, 1925, that bleak and snowy day when a child who would become a towering revolutionary figure was born in a spiritless house at 134 Safi Alishah Street in Tehran. The legacy of that figure, the poet, translator, essayist, and editor Ahmad Shamlou (1925-2000), known by his pen name, A. Bamdad or Alef Bamdad (meaning A. Dawn) — a legacy of unflinching struggle for creative and political freedom — continues to grow.

Shamlou’s birth year was pivotal. Reza Khan, a military officer in the Persian army of the Qajar dynasty who had dissolved the old government, was declared Reza Shah, the founding king of the new Pahlavi dynasty. In his drive towards modernization, Reza Shah enforced, against opposition from the clergy, the unveiling of women. In 1935, he also changed the country’s name on the roster of nations from Persia to Iran.

Throughout the 20th century, Shamlou witnessed foreign meddling in his homeland. In 1941, during World War II, English and Soviet forces occupied neutral Iran for six days, opening a north-south supply route that caused much havoc and famine and compelling Reza Shah to abdicate in favor of his son Mohammad Reza, who would rule the country until he was deposed in 1979.

Then came the CIA- and MI6-backed coup of August 1953, which overthrew Iran’s democratically elected Prime Minister, Mohammad Mossadegh, whose government’s policy was to nationalize Iran’s oil industry. The Shah, who had fled Iran for Italy, returned to power. This set the stage for the 1979 revolution that ended the Shah’s reign and replaced it with the current Islamic regime, which forced women back into hejab, despite popular opposition.

Another major world event has been unfolding in Iran since September 17, 2022, after 22-year-old Zhina Mahsa Amini died of head injuries while in the custody of Iran’s morality police for allegedly not wearing her hejab properly. Two young journalists documented Amini’s hospitalization and funeral for the world to see, though this kind of state suppression and brutality is a norm in Iran. Amini’s name became the spark of a revolution, unleashing 43 years of pent-up rage against the Islamic regime. The two journalists, Niloofar Hamedi and Elahe Mohammadi, have been arrested and accused by the Islamic regime of being foreign agents of the CIA.

Women, men, and young students have poured into the streets all over Iran in acts of civil disobedience. The government has inflicted military-grade warfare on its people. Tens of thousands of protestors have been arrested. Civilians, including children, have been murdered and terrorized in gross violations of human rights. But the freedom fighters persist, awing the world with their valor and vision.

Shamlou is very much a poet for our times, and for the ages. His career started when he awakened to the injustices in his country and dropped out of school to educate himself. His initial response to what he saw was political activism, until he discovered that the pen was mightier.

By the mid-20th century, Persian poetry was undergoing a renaissance and transformation, largely thanks to the efforts of Nima Yooshij (1895-1960), who reformed the florid language and fixed forms of classical Persian verse, which was rife with candles and moths and taverns and lady wine-bearers. These images no longer reflected the concerns of a bold, new generation. Shamlou drove this march toward Iranian Modernism further, pushing language, form, and content beyond Nima’s achievements, charging Persian poetry with a combination of humanistic ideas and literary innovations. One aspect of his genius was his ability to synthesize the east and the west, the high and the low, democratizing his literary mode without simplifying it. He speaks as and for the “everyman” in a remarkably wide variety of registers.

Shamlou authored more than 70 books, including 17 collections of poetry and dozens of translations, as well as children’s books, and a living compendium of street language, proverbs, idioms, and folklore called The Book of the Alley. He also wrote many essays and reviews, and edited literary journals. His body of work is a chronicle of Iran’s volatile cultural and political history. The themes of Shamlou’s poems range from love to social strife, and many are dedicated to people who risked it all to fight for justice, including Nelson Mandela, Che Guevara, and numerous Iranian activists who were executed under the Shah and the Islamic regime. Shamlou himself was arrested, interrogated, censored, banned, and imprisoned twice during the Shah’s reign. Yet he and his work survived every attempt to silence him. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1984, but his real “Nobel” is the esteem the Iranian people have for their “Master Poet of Freedom.”

The urgency of the struggle for freedom has not subsided in Iran. Evin prison in Tehran, where the best and the brightest have been brutalized for decades, is now overfilled.

The slogan of Iran’s current woman-led uprising is “Woman, Life, Freedom” — originally, in Kurdish, “Jin, Jiyan, Azadi.” The anthem of this revolution is a song compiled from a mantra of tweets and messages from people expressing why they’ve taken to the streets, starting with the Persian word, “Baraye” which means “For (the sake of)” or “Because of.” The song went viral and was submitted for Grammy consideration. Its composer, Shervin Hajipour, was arrested by the regime and charged with inciting violence. After his release, he has gone completely silent. Here are excerpts from the song:

For just the dream of a normal life for you and me

For all the children starving for a loaf of bread

For empty promises of heaven in the afterlife

For all the beautiful minds in captivity

For just a glimpse of a peaceful life

For women, for life, for liberty.

Cries for liberty have persisted for four generations since Shamlou began to write. His 1954 poem, “Of Your Uncles,” inspired by the poet and political activist Morteza Keyvan (1921-1954), who was arrested and executed after the 1953 coup, is a forerunner of the current revolution’s mantra. Its refrain is “(Not) For the Sake of,” a phrase I’ve truncated in this translation.

Of Your Uncles

for little Siavoosh

Not for the sun’s sake, not for the saga’s sake

but for the sake of her little rooftop’s shade

for the sake of a song

smaller even than your hands

Not for the woods, not for the sea

but for a lone leaf

for a droplet

brighter even than your eyes

Not for walls

but for a straw hedge

Not for everyone’s sake

but perhaps for the enemy’s newborn’s

Not for the world’s sake

but for your home’s

for your small conviction

that humans are a world unto themselves

For a dream of a moment with you

For your little hands in my big ones

and my full lips

upon your innocent cheeks

For a swallow in the wind

when you rejoice

For a dewdrop upon a leaf

when you sleep

For a smile

when you shall see me near

For an anthem

For a story in the coldest of nights the darkest of nights

For your dolls, not for adults

For cobblestones that lead me to you

not for distant highways

For drain pipes — when it rains

For hives and little bees

For the white herald of the cloud in the open still sky

For your sake

for the sake of all things pure and small

they fell to the earth

Remember them

I speak of your uncles

I am speaking of Morteza.

And as citizens are murdered in their homes and in prisons, as protestors, passersby, and students walking home from school are left to lie, beaten and dead, on the naked streets, having chosen to give everything up for liberty and justice, I think of Shamlou’s “Children of the Depths” (1975), a lamentation for the most desolate of children who wrestle with the abyss of their lives. The poem is dedicated to Ahmad Zibaram, a guerrilla who died for his activism in 1972, and ends with a reference to Kaveh, a figure in Ferdowsi’s 10th-century epic, Shahnameh (The Book of Kings). After losing several of his children to the serpent-shouldered king Zahhak, whose serpents’ hunger could only be sated by a daily meal of two human brains, Kaveh refuses the king his last child and raises his blacksmith’s apron upon a spear as a standard of rebellion to lead the overthrow of the tyrant.

Children of the Depths

song lyrics on the martyrdom of Ahmad Zibaram

for Alireza Espahbod

They grow in a street-less city

in capillaries of back alleys and dead-ends

tarred in brick-kiln ash and contraband and skin sores

colored knucklebones in pocket and slingshot in hand

Children of the depths

Children of the depths

A merciless swamp of a fate ahead and

vitriol of weary fathers behind them

curses of dispirited mothers in their ears and

no hope and tomorrow in their fist

Children of the depths

Children of the depths

They blossom in the spring-less forest

bear fruit on rootless trees

They sing with bleeding throats and in defeat

hold high a banner in hand

Kavehs of the depths

Kavehs of the depths

If Shamlou were alive today, how many more poems would we have to catalog this endless carnage, to consecrate these martyrs to freedom?

¤

The lyrics from “Baraye” were excerpted and translated from the Persian by Niloufar Talebi. “Of Your Uncles” (from Garden of Mirrors, 1955) and “Children of the Depths” (from Little Songs of Exile, 1980) by Ahmad Shamlou are translated from the Persian by Niloufar Talebi, with advise from Lida Nosrati, Saied Kazemi, and Alireza Abiz, and are based on the print versions in Collected Poems of Ahmad Shamlou (Negah). Ahmad Shamlou’s works are in the public domain in the United States. Additionally, translation and publication rights were granted by Aida Shamlou and the Alef Bamdad Institute that manages Ahmad Shamlou’s estate.

Photograph by Hadi Shafaieh.

LARB Contributor

Niloufar Talebi’s hybrid memoir Self-Portrait in Bloom (2019) is a literary biography with selected translations of Ahmad Shamlou. Its companion opera, Abraham in Flames (2019, co-created with composer Aleksandra Vrebalov), and her TEDx Berkeley talk are based on her encounters with Shamlou. She is the editor/translator of Belonging: New Poetry by Iranians Around the World (North Atlantic Books, 2008). Her theatrical projects include ICARUS/RISE (2007), The Persian Rite of Spring (2010, Los Angeles County Museum of Art), Fire Angels (2011, Carnegie Hall), and other works at Stanford Live and the Kennedy Center. Ms. Talebi was a 2021-2022 Fulbright U.S. Scholar to the country of Georgia and currently working on a book on Home. www.niloufartalebi.net IG: @niloufar_talebi_artist

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!