World Revolution of Youth! On Abigail Susik’s “Resurgence!”

Johanna Isaacson reviews Abigail Susik’s anthology “Resurgence! Jonathan Leake, Radical Surrealism, and the Resurgence Youth Movement, 1964–1967.”

By Johanna IsaacsonSeptember 30, 2023

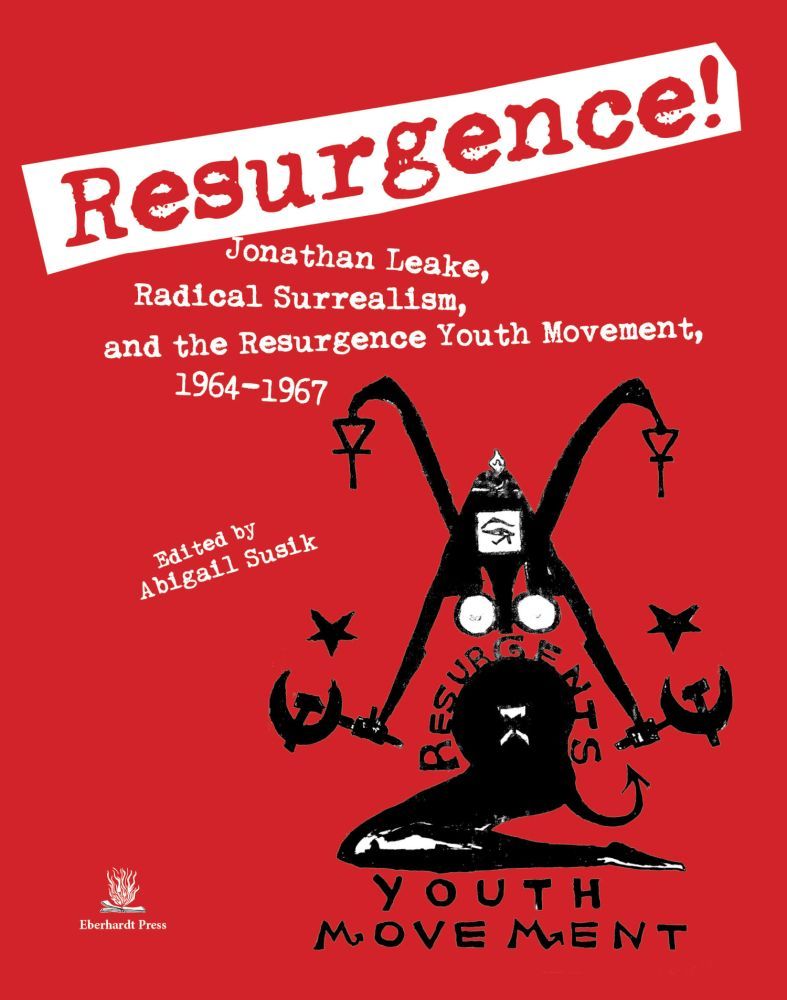

Resurgence! Jonathan Leake, Radical Surrealism, and the Resurgence Youth Movement, 1964–1967 by Abigail Susik. Eberhardt Press. 224 pages.

IT’S MAY 2023, and I’m here to report that young people are not doing well. As a community college teacher in California’s Central Valley, the most impoverished part of the state, I receive apologetic messages every day describing the depression, illness, family strife, domestic abuse, houselessness, and other dire life circumstances that affect students’ performance in school. Ernst Bloch, in his exploration of “the principle of hope,” says that “[b]old youth imagines it has wings and that all that is right […] can only be […] set free by youth.” One’s early years should be guided by this exuberant anticipation and assuredness, but many of my students come of age with their wings already clipped.

Even ambitious and relatively happy students seek little more than they are getting. For most, a boring middle-class job and a 30-year mortgage are considered a stunning piece of luck. The kind of abundance that Kristin Ross calls “communal luxury”—euphoric, prefigurative collectivity aimed at dismantling capitalist waste, violence, and privatization—is not on their radar. In the face of this imaginative conservatism, it is difficult to recall the not-so-distant past when the United States was infected with a contagiously exhilarating sensibility among the young, a feeling of entitlement to joy, comfort, free time, and love—not just for oneself but for everyone.

Resurgence! Jonathan Leake, Radical Surrealism, and the Resurgence Youth Movement, 1964–1967, edited by Abigail Susik, has rescued a fragment of this submerged history by collecting and working with an engaging array of contributors, including Paul Leake, Penelope Rosemont, Sean Lovitt, and Maggie Wrigley Leake, to frame the life and work of Jonathan Leake, founder of the 1960s collective Resurgence Youth Movement (RYM). While researching her previous book, Surrealist Sabotage and the War on Work (2023), Susik came across Leake’s legend through surrealist artist Penelope Rosemont. After painstakingly tracking down Leake, copies of RYM’s publications, and others involved in the group, Susik worked with the independent publisher Eberhardt Press, an innovative and extremely small-scale DIY project based in Portland, Oregon, to share this obscure gem of radical history.

Jonathan Leake believed that he, his entire youth cohort, and indeed the world were entitled to communal luxury. Unlike my students, he was born into privilege. But his wealth did not liberate him from what he perceived to be stifling cultural, political, and psychological norms. Instead of following the well-worn path to middle-class ease, he blew up his predetermined individual future and became a full-time agent for collective transformation. At age 15, he was already an activist on the brink of expulsion from high school. Characteristically, he went out in dramatic fashion after attempting to burn down the chapel at his boarding school. Following this, he was consigned to a mental hospital, only to be freed by a group of radical friends who broke him out by disguising themselves as Catholic priests.

By age 16, he had fully given himself to the radical scenes in New York City, participating in Industrial Workers of the World agitation. But finding himself at odds with the old guard, he instead immersed himself in youth rebellion, rock and roll, drug culture, surrealism, and insurrectionary anarchism, while allying himself with Black and Puerto Rican liberation movements. Taking up surrealism “as a direct-action praxis for revolution,” as Susik puts it, Leake committed to a tempestuous path that conflated art, politics, and everyday life, striking Rosemont as a person who “desired to push us and our consciousness to the very edge and over that edge.”

Leake’s extravagant and passionate politics drew other young radicals to him. Together, probably inspired by the Harlem uprising of 1964, they formed RYM. Those involved participated in radical actions such as rent striking, street protesting, and fighting cops while producing incendiary literature in the form of 12 issues of an underground zine entitled Resurgence.

The group both directly and indirectly served as a formative source for the radical underground publications East Village Other, Rebel Worker, Heatwave, and King Mob Echo; revolutionary groups such as the Wobblies, the Diggers, Provo, and Black Mask/Up Against the Wall Motherfucker; and politicized Black and Latino street gangs and underground comix. Conservative pundits saw Leake and RYM as particularly degraded examples of youth nihilism, and this notoriety only spread the word of these incendiary surrealists further into the counterculture and radical milieus. As anarchist youth movement scholar Sean Lovitt argues: “By bridging the anarchist and artistic subculture, Resurgence gave voice to a new radical tendency that resonated with young militants.”

RYM’s disbanding was tragic, abrupt, and political. The group itself was murdered when Leake’s close collaborator, Walter Caughey, was stabbed to death in what many believe was a retaliation for Caughey’s collaboration on rent strikes with Black and Puerto Rican activists. At age 21, Leake’s time with RYM was over, but he did not abandon his radical path. His involvement with creative youth uprisings lived on through his participation in punk and other radical communities. In her contribution, Maggie Wrigley Leake, his partner, tells of his post-1960s involvement in anti-eviction movements, mutual aid, direct action, squatting, poetry, and music in New York. And as Lovitt argues, apart from Leake’s direct activities, RYM’s sensibilities continue to resonate within contemporary anarchist zines, affinity groups, and black blocs affiliated with Occupy, Black Lives Matter, and other recent movements.

The centerpiece of the book is a reprinting of significant selections of the underground publication Resurgence and Leake’s unpublished memoir “Root and Branch,” both of which will be essential to researchers of American radicalism of the 1960s and ’70s. These are important and highly endangered materials; in fact, there is only one known existing copy of Resurgence’s fourth issue.

In her essay “The Left of the Left,” Susik prepares us to navigate Resurgence by framing its main concerns and highlights, while elaborating on RYM’s views on surrealism and anti-racism. And Leake’s collaborator and brother (who was just 14 when he began participating in RYM) describes it as a magazine that “provided a literary platform where ideas could be expressed, insurgency news could be shared, and poetry had a voice.” Produced with what Lovitt describes as a “wild design style and unpolished, DIY layout,” the magazine’s manifestos and poetry are a mix of surrealist aesthetic declamations, calls for youth insurrection, anti-capitalist screeds, mystical incantations, and allegiance with and reportage on global and anti-racist uprisings. As the journal’s masthead reads, the group was committed to the following:

permanent insurrection : : antipolitics : : cultural sabotage : : towards the structive personality : : invisible sociology : : history as hallucination : : subversive fantasy and science fiction : : juvenile delinquency : : cosmogony : : prophecy : : autonomy : : surreality : : studies in the language of night : : a mantic workshop : : fraturgency:::::::::

As the group’s thoughts evolved, they underscored the relationship of teen revolt to key issues of the day: the Berkeley Free Speech Movement, the anti-war movement, Black Power, and an array of Third World guerrilla liberation movements. They insisted that poetry, nomadism, and juvenile delinquency were political, contrasting these to the conformist culture that was building to “THE NAZIFICATION OF AMERICA.” They read messages of youth resurgence in contemporary psychedelic and folk music: “Something is happening, but you don’t know what it is, do you, Mr. Jones?” And of course, world revolution is “dancing in the streets.” They took up the slogans of Black rioters: “BURN BABY BURN!”

One of the journal’s unique contributions was to see surrealist expression as totally contiguous with “teen revolt,” viewing these two strands of action and expression as the means for white youth to support ghetto uprisings and Third World guerrilla warfare. Through poetry, reportage, and manifestos, they broadcast militant calls—“BARBARIANS UNITE,” “LET THE STATE DISINTEGRATE,” “SUBMERGE EUROPE,” “DEFEND HALLUCINATIVE FORCES,” “ART IS MAGIC”—all building to a “WORLD REVOLUTION OF YOUTH!”

The confluence of bold didacticism and surrealist dream logic infuses the paper’s literary contributions. One poem asserts, “The new world shows itself on the pavement, in the grey teeth of the rain.” Another menaces: “America / You might love me / If I wrote poems about humility / But today I am hungry and I tell you / The fat of yr naked right arm makes my mouth water.” An ode to the miseries of capitalist half-life and violence complains: “Here, sullen iceboxes yawning death to our bellies, here ravines stuffed with bodies, and houses gravestones to life’s green throb. Here we need the need that makes struggle our song. Here, the waiting, here the bulk blasted babies on ironclad horizons.”

Then, this manifesto-like prose poem goes on to meditate on the potentiality springing from this decay:

We are born in order and disorder, the sperm and egg within us, a stillbirth careened into the garden of earthden, eyes glazed and fingers melting, body and soul arched forward, wondrous, pondersome, colossal, agitators of atoms and energies[,] children of universal challenge and change.

The rage, wonder, and transformative imagination pulsing through this journal bypasses the “capitalist realism” that makes the youth of today feel that their lives are over before they have even started. We may see this as impractical and hubristic, or we can view the demands and declamations in Resurgence as a higher realism in which transformative hopes actually matter. As Rosemont says of Leake: “His information was accurate.”

The surrealist insistence on demanding the impossible throws established discourses of moderation and maturity into relief. According to mainstream pundits, youth anarchy is irrational and violent while centrism is measured and pacifist. Yet it is the gradualism that characterizes “sober-minded” politics that has led us to this point, in which our daily lives are immersed in violent extremes—environmental catastrophes, police murders, youth suicides, and on and on.

The revolutionary elan that travels from RYM to today’s black bloc is belittled by “mature” custodians of “civil” language and actions. But this dismissal is ultimately a way of disenfranchising youth in all areas of life. “If resurgence is childish,” one screed from Resurgence puts it, “it is because some of us are children and children will also make the revolution.” RYM diagnoses the feelings of so many youths today who are “desperate, afraid and tempted to withdraw and just try[ing] to survive in a system that has little tolerance for [them].” The group’s revolutionary consciousness transformed them into a collective that “will do all, give all, to see our children grow and build and love in a world free from war and waste.” RYM’s boldness proves Bloch’s emphasis that, ideally, for youth, the “voice which calls for things to be different, to be better, to be more beautiful, is as loud in these years as it is unspoilt, life means ‘tomorrow,’ the world ‘room for us.’”

In preserving and framing RYM’s short, wild life, Susik and the book’s other insightful contributors join a long line of essential workers: custodians of what Greil Marcus calls the “secret history” of artistic rebellion that is consistently written out of dominant narratives. Those who refuse anything less than the “revolution of everyday life” commit to a politics of love and personal transformation that surpasses abstract political structures, and for that they are dismissed as childish dreamers. RYM was a beating heart of this sensibility in the 1960s, and their riotous light is in danger of being extinguished and forgotten.

In these compromised times, we should treat ourselves to the unmitigated pleasures of uncompromising demands: “NO MORE LAWS, NO MORE PRISONS, DESTROY POLITICS! DESTROY RELIGION, DESTROY THE OLD WORLD! TEENGANGS UNITE! GUERILLA! GUERILLA! BUILD THE NEW MOVEMENT OF REVOLUTION!” RYM’s story helps us remember that the accepted arbiters of culture and politics may tell us we can’t have everything (or anything), but that doesn’t mean we have to stop wanting, demanding, and fighting for it all.

¤

LARB Contributor

Johanna Isaacson writes academic and popular pieces on horror and politics. She is a professor of English at Modesto Junior College and a founding editor of Blind Field Journal. She is the author of Stepford Daughters: Weapons for Feminists in Contemporary Horror (Common Notions Press, 2022) and The Ballerina and the Bull: Anarchist Utopias in the Age of Finance (Repeater Books, 2016), as well as many articles in academic and popular journals. She runs the Facebook group Anti-capitalist feminists who like horror films.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Utopian Horizon of Memory Art: A Conversation with Andreas Huyssen

Abigail Susik speaks with Andreas Huyssen about his book “Memory Art in the Contemporary World: Confronting Violence in the Global South.”

The Kids Want Communism: A Conversation with Joshua Simon

Joshua Simon talks about his years-long art project that celebrates the archival histories of communism.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!