Why Does Mike the Millennial Meander?

Amy Silverberg on Mike Roberts's "Cannibals in Love."

By Amy SilverbergOctober 26, 2016

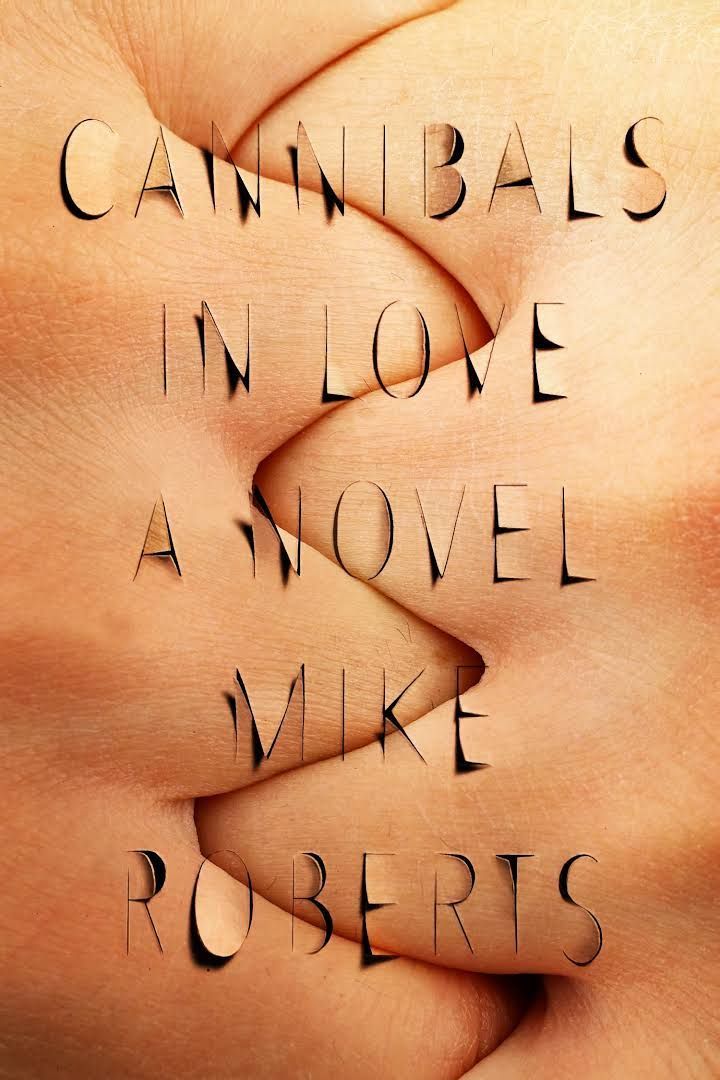

Cannibals in Love by Mike Roberts. FSG Originals. 352 pages.

MILLENNIAL is a loaded term, meant to encapsulate the generation born between 1982 and 2004. Think pieces abound on millennial behavior — our narcissism and attention deficit disorders — how to explain our devotion to social media, or why so many college grads still live with their parents. I am 28, and I fit (age-wise, at least) into the millennial category, for better or worse. Regardless, I cringe at the sight of the word; I cringed just typing it! Like most of my peers, I find the stereotypes of my generation to be just that: some true, some false. For instance, I am relatively inept when it comes to technology, and I have never once taken a selfie. And yet, as a kid, I did receive trophies just for participating in sports, regardless of how infrequently I touched the ball. I, too, was released into a professional world in which the options seemed limitless — if only you’d agree to be a professional intern. Most important, I understand the free-range anxiety inherent to growing up in the shadow of the most monumental terrorist attack the United States has ever seen — a feeling which Mike Roberts’s debut novel, Cannibals in Love, deftly interrogates.

Roberts’s protagonist, also named Mike, is fresh out of college, and struggling to find a place in the adult world. In 18 short vignettes, we see Mike work a series of odd and often humiliating temp jobs and date a variety of women — one more seriously than the rest. He bounces around from his hometown in upstate New York to Washington, DC, to Portland, to Paris, to Kansas.

The novel opens with him isolated in a sea of traffic, counting lampposts for the city of Lockport in upstate New York, where he grew up. Frustrated with the mind-numbing monotony of the job (marking the location of every burned out lamppost in need of attention), Mike is unable to connect with his elderly co-worker, Don. While Mike is just passing a little time before the next best thing, Don seems to have resigned himself to the bleakness of this job and the little effort it entails. Eventually, Don’s depression becomes too much for Mike to bear:

I sat down in a bus shelter and gave all four lampposts a single GPS location. And then I didn’t move. I didn’t know where to go, really. I stared out across the buzzing traffic, feeling shipwrecked. I didn’t care about Don’s suffering. I was thinking about myself, which is the only thing you know how to do when you’re young.

This is a fitting beginning, with Don as a harbinger of what might happen to Mike if he never gets his shit together. In these instances, Mike-the-millennial is like an experiment in a petri dish, unsure of how to react to stimuli. He tries a little booze here, a dash of violence there, and waits to see where the one or the other might lead. He’s a person learning how to navigate the world. And this world is utterly confusing. “Terrorism was not some abstraction on the television,” reflects Mike-the-narrator:

It was the promise of endless war. It was the fear of people and buildings. It was the suspicion of strangers and foreigners. It was the avoidance of crowds and public transportation. It was the brand-new paranoid connections that bloomed inside our heads with no clues for how they got there, or what to do next.

After all, how should someone respond to a stimulus that may or may not be there? The dangers in Mike and his friends’ lives are nebulous and widespread. Their pulses race as though they’re hiding, but they’re not sure what they’re hiding from. They’re often angry, but don’t know where to direct the anger. They’re at a loss as to how a person should be: “It made sense to behave erratically now,” Mike says, after hearing his favorite disc jockey on the radio break character and dedicate David Bowie’s “Heroes” to all the brave women and men of law enforcement. Mostly, Mike grapples with his anxiety in predictable ways — he whittles away the time in bars and tries to meet girls.

There is one woman in particular, Lauren Pinkerton, who becomes his on-again, off-again girlfriend through most of the novel. Upon their first meeting, he says, “Lauren radiated something bigger than confidence, bigger than sex.” Be that as it may, after their initial sexual encounter, Mike is often at the mercy of Lauren’s flightiness, the ebbs and flows of her moods, which are usually a mystery to him. Later, things between them get complicated; rather, they complicate their lives with constant fighting. They fight because they’re bored. They fight because they’re dissatisfied with their lives and jobs and economic status. They fight often for the sake of fighting. Needless to say, the relationship is tumultuous. And yet, this also seems indicative of a generational attitude. Roberts pinpoints a familiar malaise in his protagonist (caused, perhaps, by a surplus of romantic options and access to these options through technology — but this is only my theory), although like all good characters, Mike contains multitudes: he’s a romantic, yet he doesn’t necessarily want to untangle his own romantic discontent; he’s not quite sure what he wants — but he definitely wants. This is what makes the book so compelling: watching Mike attempt to channel his anxiety-ridden longing toward something that actually matters.

At his worst, Mike can be narcissistic and whiny. He makes mountains out of molehills and then curses while he climbs them. He is, in a word, self-destructive. “We were the children of privilege,” Mike-the-narrator explains, “insulated; overeducated; underemployed. Eternally running away from home and playing at being adults.” He has grown up with upper-middle-class privilege, and he’s able to articulate this privilege clearly, especially when describing the way in which he and his friends create their own problems. For example, when Mike drinks too much and crashes his bike, he must trick (or convince? charm?) the police into letting him get away unscathed. Much of the novel is like this — a series of events in which the protagonist outruns any real consequences. Perhaps it’s the irrepressible confidence of the young; they believe any bad decision can be undone. Then, too, there’s the underlying knowledge that Mike is not alone in the world. He has a safety net: parents he can count on, who will save him from any situation that becomes dire. It’s Roberts’s gimlet-eyed attention to Mike’s selfishness that allows the character to become fully realized, the kind of guy who might careen drunkenly off the pages and into your bushes on his bike. You might bump into this bleary-eyed person in a bar, or at your own temp job — he’s the antihero and the everyman; he knows what not to do, but does it anyway.

Eventually, Mike does channel his longing into something positive. You’ve probably guessed: he becomes a writer, or rather, he gives in to his long time desire to write. But though I did see this career path coming, it felt inevitable in a pleasurable way. From the beginning, Mike has all the requisite trappings: he’s an astute observer of his surroundings; he is ruthlessly self-aware and often self-deprecating; he drinks too much and then laments how much he drinks. Most important, he’s trying to make sense of the world and of himself. In a postmodern move, Mike-the-character blends with Mike-the-narrator until they are one in the same. In this way, the author Mike Roberts embeds his own definition of writing in his novel about a guy named Mike who becomes a writer: “I was interested in the gaps and discordances of experienced time,” he writes. “I was working through the role of memory and imagination as it functions in its fullest capacity, to fill those empty spaces with meaning. Because what was this construction, after all, if not fiction?”

During most of the novel, Mike talks about a swollen book project, previously written, that he knows will never come to fruition. He goes on to explain that his next novel will be “assembled like a mixtape, with all of the emotional modulations of an object that is constructed with an order and intention.” The outcome? Cannibals in Love. The vignettes serve as a collage, a watercolor study of growing up in a very particular time, in a very particular world, in which a silent and invisible danger lurks behind every tower. Whether funny, angry, or terrified, Mike has finally found his voice: “the voice I actually speak in,” he tells a friend. “The one I use in an email. Or a joke. That’s the way I’m trying to write.”

Personally, I could listen to this voice all day. It’s as if it belongs to a friend I grew up with, or someone I met at a bar, or found counting lampposts in my hometown — strangely familiar and wise beyond his years.

¤

LARB Contributor

Amy Silverberg is a Doctoral fellow in Fiction at USC. Her work has appeared in The Collagist, Joyland, Hobart, The Tin House Open Bar, and elsewhere. She also performs standup and sketch comedy around Los Angeles. You can follow her on Twitter @AmySilverberg.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Writing in a “Bubble of Idiocy”

Alyssa Oursler talks to Chloe Caldwell about her new memoir, "I'll Tell You In Person."

The Course of Love: A Crash Course in the Long-Term Relationship

In "The Course of Love", Alain de Botton debunks the myth of “happily ever after”.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!