Where Are You Taking Me, Father?: Three Sons Live Through Apartheid South Africa

Kaleem Hawa reviews three recent books on South African apartheid.

My Father Died for This by Abigail Calata and Lukhanyo Calata. Tafelberg Publishers Ltd. 272 pages.

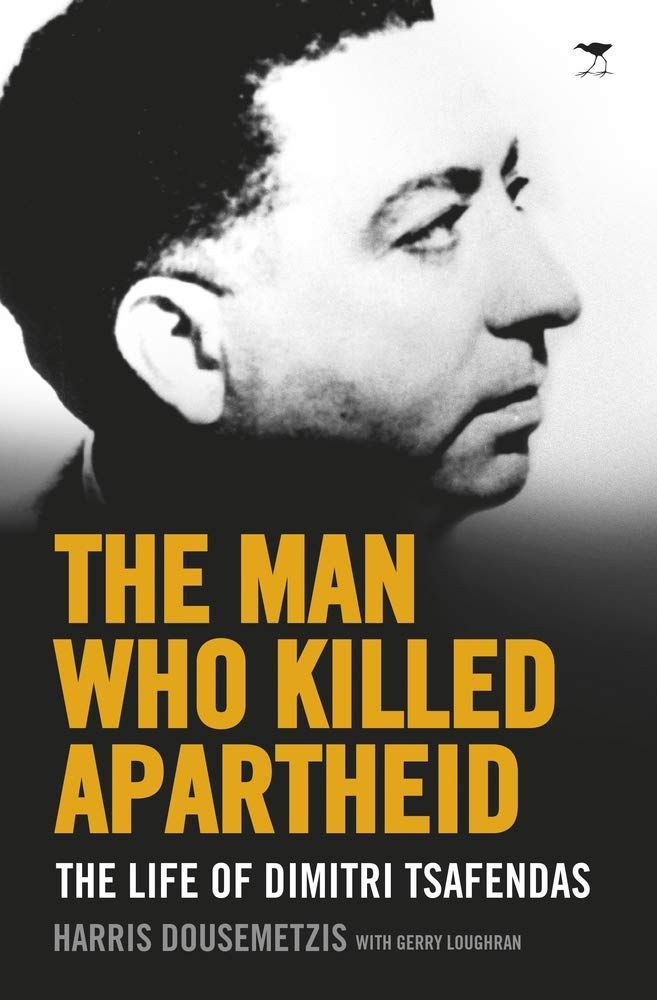

The Man Who Killed Apartheid by Harris Dousemetzis. Jacana Media. 504 pages.

Verwoerd: My Journey through Family Betrayals by Wilhelm Verwoerd. Tafelberg. 280 pages.

THE MAN WAS BUYING a knife. It is morning in Cape Town, 1966, and Dimitri Tsafendas enters the store on Hout Street, knowing exactly what to look for — his father used to make knives, when he worked for the Iscor Iron and Steel Works in Pretoria. Dimitri buys the knife, and then another. Hours later, in the messengers’ room of the House of Assembly, Dimitri takes out a well-worn photo of his father, the Cretan-born Michalis, an “engineer-cum-revolutionary.” He looks at it once, wondering what his father would think about what he was about to do, before returning it to his wallet and entering the parliamentary chamber. He walks up calmly to the figure seated at the desk before him, and he stabs.

There is a brief, stunned silence, and then a flurry of action:

The chamber became deathly silent as Dr Morrison breathed air noisily into Dr Verwoerd’s lungs and another doctor rhythmically pressured his heart. The prime minister remained inert. Dr Radford felt for the pulse in the victim’s left wrist. It was absent and he and Dr Fisher, speaking quietly, agreed that the prime minister was dead. […] Ghostly pale, South Africa’s leader lay slumped in his seat, his head tilted back. He had never uttered a word or a sound from beginning to end of the attack.

As the seventh prime minister of South Africa, Hendrik Verwoerd, lay bleeding on the chamber floor, the MPs and spectators began to realize that he was dead:

Two MPs collapsed in the lobby, others bellowed with rage. Many stood stricken, uncomprehending or unwilling to accept what they had witnessed. Cabinet Minister P.W. Botha, a future prime minister, turned to Helen Suzman, the lone MP for the Progressive Party and the only anti-apartheid voice in the House, and shaking his finger in her face, shouted furiously, “It’s you who did this, all you liberals. You incite people. Now we will get you. We will get the lot of you.”

This is a moment that has been replayed throughout South African history, marking the murder of a man considered “the architect of the world’s most ruthless, racist regime since Nazi Germany.” The assassin, Dimitri, would be hurriedly depicted as insane, tried by the ruling National Party, and imprisoned with little fanfare.

But questions had always lingered. In April 2018, a “Report to the Minister of Justice, advocate Tshilio Michael Masutha, in the Matter of Dr Verwoerd’s Assassination” was submitted by Judge Jody Kollapen on behalf of Harris Dousemetzis, a journalist and academic. The 2,192-page, three-volume report ultimately advances the case, long overlooked and marginalized, that the assassination of Hendrik Verwoerd was not an act of insanity by Tsafendas but was instead a politically motivated act of resistance by a mixed-race activist and lifelong communist disgusted with the apartheid state. Released as a follow-up in January of 2019, Dousemetzis’s book The Man Who Killed Apartheid dramatizes his research and represents the most exhaustive excavation of the life and motivations of Dimitri Tsafendas that has ever been published. It joins two other books that came out in this past year, each addressing what we owe our families in the context of intergenerational trauma and reconciliation.

¤

Almost two decades after Verwoerd’s assassination, another politically motivated murder will occur, this time in Cradock, a rural town in the Eastern Cape. In 1983, Fort Calata and Matthew Goniwe help found the Cradock Residents Association and Cradock Youth Association, radical campaigns of nonviolent resistance against apartheid that attempt to “render the country ungovernable,” and which begin to spread to townships all along the Cape.

After departing Cradock, Matthew and Fort — alongside two other activists, Sparrow Mkhonto and Sicelo Mhlauli — are ambushed on the road by (it is believed) a secret police hit squad. They are abducted, tortured, and killed, their bodies discovered a few days later. The murder of the “Cradock Four” is a central focal point of Lukhanyo and Abigail Calata’s memoir, My Father Died for This. And while the murders have been written about significantly in many accounts and articles, Lukhanyo, who is Fort’s son, produces the definitive personal portrayal, rigorously researched, and yet also raw and pained.

The book begins with another form of activism. Lukhanyo is among a group dubbed the SABC 8, eight dissident journalists dismissed by the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) in 2016 for speaking out against its “state capture” and corruption. After his dismissal, Lukhanyo issues a statement condemning the SABC’s actions and is asked to come to the headquarters of the African National Congress (ANC) at Luthuli House in Johannesburg, where he briefs the deputy secretary general, Jessie Duarte. He is eventually reinstated.

His statement, which comes during the 31st anniversary of Fort (the book’s eponymous father) being murdered, is part of a lineage of activism in Lukhanyo’s family. His great-grandfather, Arthur “Tatou” James Calata, was a famous South African politician and priest, who served as the secretary general of the ANC through most of the 1940s, and later, as canon of Grahamstown. Tatou’s wife and Lukhanyo’s great-grandmother, Miltha, was herself arrested for leading strikes and stayaways when Tatou was serving house arrest for participating in the 1952 Defiance Campaign against the Pass Laws.

It is clear in reading the book that Lukhanyo perceives a traceable lineage between the lives of his great-grandfather, his father, and his own, and that there pulses between them a commitment to liberation that transcends the specific political contexts in which they operated.

In many ways, Dimitri Tsafendas is similarly motivated by this commitment to liberation. Back in 1966, it slowly becomes clear to General Hendrik van den Bergh, the intelligence official presiding over Dimitri’s arrest after the assassination, that his charge has fought alongside the communists during the Greek Civil War, has been arrested many times by the Portuguese for his anti-colonialism, and is a supporter the British anti-apartheid movement, announcing at a meeting in London years before his assassination of Verwoerd, that he was willing to do “anything that would get the South African regime out of power.” As the regime begins to realize that Verwoerd’s murder is politically motivated, they undertake an extraordinary process of concealing Dimitri’s commitment to communism.

But while the book begins with the assassination and its aftermath, it quickly backpedals in order to explore Tsafendas’s upbringing. Like Lukhanyo, Dimitri was named in relation to his great-grandfather, Dimitrios, a “famed rebel chief.” His father Michalis was a Cretan living in Mozambique (then a Portuguese colony), while his mother was half-Mozambican and half-German. Raised with his half-siblings in Alexandria, and later, in Mozambique, Dimitri starts making bombs, is exiled on account of his politics, and eventually returns to South Africa, having amassed a massive Portuguese intelligence dossier detailing his subversions against the state.

Dousemetzis allows himself to ask moral questions in his work as well: when, if ever, is violence justified in the face of injustice? And while this idea has been explored by many thinkers, the context here is complicated by the fact that, for all intents, Dimitri is part of a social and cultural class that is inoculated from the most insidious effects of apartheid. Dousemetzis is interested in what could bring a man not expressly threatened by the apartheid system to kill its leader, to “remove the monster’s head,” believing “the body would soon die”?

The book’s third chapter — entitled “The Son of an Anarchist” — details Dimitri’s relationship with his father Michalis, who was “a deeply committed radical: anti-racist, anti-royalist, anti-fascist and anti-colonialist.” Michalis jokes after Verwoerd was wounded by gunshot in 1960 that “it was a shame the prime minister survived,” and “that if he had not had a family, he would have himself have taken a gun and shot everyone in the South African parliament.” The book adds that, “not unnaturally, Dimitri worshipped his father and tried to imitate him,” and that “there was a blood tie and an ideological one between father and son.”

Dousemetzis, however, problematizes this neat linearity by also exploring Dimitri’s burgeoning racial consciousness and the ways it ties his sympathies to that of the black South Africans. Dousemetzis tells of Dimitri first reading Uncle Tom’s Cabin as a child:

The story of racial discrimination and violence in America shocked the boy deeply and had a tremendous effect on him. Weeping, he ran to his parents and implored his father to tell him if such things really happened. […] This was the moment when the United States became a hate figure for the young Dimitri. Unaware of his own black origins, he felt a deep need to fight for equality for all, if only to prove that he was not like the whites in the book.

Dousemetzis suggests this was difficult, that “when Tsafendas was a child he was referred to as ‘blackie,’” that after discovering his own racial heritage he “never hid his mixed origins during his time in apartheid South Africa, determined to dissociate himself from the racist rule around him.”

In fact, he comes to value it; shortly before the assassination, Dimitri writes a letter petitioning the state to be reclassified from “White” to “Coloured.” His application is denied.

¤

On January 25, 2014, a different sort of letter is being written. It begins, “Dear Oupa Hendrik. Nearly 50 years ago, I was drinking milk in your lap. It’s been almost 50 years since your bloody death. Still, it feels strangely right to write this letter to you now.”

The writer is Wilhelm Verwoerd, the grandson of Hendrik. This year, Wilhelm published My Journey through Family Betrayals, which details his and his family’s relationship to his grandfather. In the book’s opening, Wilhelm visits his grandfather’s memorial collection in Orania, an Afrikaner settlement. There, he sees the clothing the elder Verwoerd wore before he died — Dousemetzis’s first chapter is replayed, but this time as an adopted memory, a faded relic to a man long-dead:

[W]e find ourselves in front of a display cupboard with the clothes my grandfather had been wearing on the day of his murder. Besides the old-fashioned, formal work outfit there are familiar pictures of him as prime minister. […] The jacket is marked with four red flags where the knife struck. The white shirt doesn’t need any pointers. The blood stains are diluted, but clearly visible.

We learn later that Wilhelm’s mother was tasked with washing the late prime minister’s clothing when it was returned to the family: “Cold water, cold water, cold water … until you’re sure there’s no more blood in the fibres of the suit. Pa asked me to do the washing, because he was not up to it.”

But, “the water continued to turn red no matter how often she repeated the process.” And she stares with horror at the scene in front of her, a baby Wilhelm in the house at the time: “‘And your hands … your hands…’ my mother said. ‘Soap and soap and soap and soap and more soap…’ ‘But the smell remained?’ ‘Yes, it lingered. Working all that time with the bloody water, the smell soaked into my skin.’”

Wilhelm reflects on “Oupa Hendrik’s” blood in his veins, on “Apartheid blood on the hands of Verwoerd.”

This legacy has haunted him throughout his life. Wilhelm was raised in the “white Afrikaner identity of Stellenbosch,” a world which would have had “no time for the ‘communist ANC.’” After graduating, he travels to Holland to continue his studies — “an innocent, protected theology student” who “ended up in this hornet’s nest,” surrounded by anti-apartheid activists and homosexuals.

He applies to a Rhodes scholarship and is accepted to study at Oxford University. In Utrecht and in Oxford, he is exposed to the experiences of black South Africans, to the writings of the international boycott movement, to activists and intellectuals who look at his family’s history through very different eyes. He starts to read books banned in South Africa and slowly his worldview begins to unravel, his increasing agitation and horror transcribed in the letters he sent home to his family and to his love, Melanie. These letters, published fully in My Journey, show a man grappling painfully with his family’s legacy. In 1986, he writes, “I am realizing more and more that apartheid is wrong, and worse, always has been; that our people (my grandfather and co.) were deaf/blind to those people (the majority) who did not agree with their ideological/theological framework.”

If the children in these three books are influenced by the settings in which they grew — Dimitri in Alexandria and Mozambique; Lukhanyo in Cradock; Wilhelm in Stellenbosch — it is often schools and schooling that serve as a locus for radicalization. This isn’t always through formal instruction — take Matthew, whose brother dropped out of school to join the ANC’s armed wing, the uMkhonto weSizwe — but for Fort, who served in Cradock’s schools, teaching was a calling, a forum to educate students in service of future resistance.

From Oxford, Wilhelm writes another letter, this time to his parents: “This must be one of the experiences which shocked and disillusioned me most lately […], that the world in which most of the inhabitants of our country have been living, especially during the past century, is so different to our world: so full of pain and rage and frustration.”

There is always pain, of course. Wilhelm and Melanie return to South Africa in June 1990 and join the ANC, an act that leads Wilhelm’s father to disown him. From early 1993 onward, Wilhelm is asked to help campaign on behalf of the ANC, traveling to rural Afrikaner communities to share their message, to challenge the prejudice.

Above all, Wilhelm is writing about what is means to betray “one’s family,” and while he is sometimes talking about his father and immediate relatives, he also defines family far more loosely, stretching it past those who are related to us simply by blood and into a collection of identities and allegiances that are often interconnected with race and gender and class. After all, Afrikaners view his grandfather as having “sacrificed his life for his volk,” and as his father reminds him on the day of their fateful reunion: “You are a traitor to the Afrikaner people. And to your grandfather.”

Tsafendas, too, is cutting against the grain of his community, a Greek–South African society that, for the most part supports apartheid, ordering their identity around whiteness to reap the benefits of the discriminatory system. Dimitri’s world, however, is additionally mediated by his experiences of estrangement as a mixed-race child.

In some ways all three authors see their obligation to their families as responsive; that is to say, that they could not and did not choose to be born with their bodies, with their histories, but that growing within those parameters requires engagement with the past. To see this as uncontroversial is to misunderstand the overwhelming erasure impulse that follows a social and racial cataclysm of apartheid’s magnitude. It is unsurprising that for most, it feels right to attempt to exist independent of all that came before, to bury the past and its pain.

For Lukhanyo, these burials are physical — his only memory of his father is his funeral. And just like Fort with his grandfather’s passing, Lukhanyo’s mother Nomonde does not get the chance to privately mourn her husband’s death:

On that cold Saturday afternoon in Cradock, an estimated 60,000 mourners not only defied a government ban to travel there, but they made the funeral one of the biggest political rallies of the time. It was a true turning point in black South Africans’ struggle against oppression and injustice.

When thousands attend the funeral, how can you ever hope to translate your pain to them? How can you ever capture and comprehend theirs? And so, time and time again, South Africa’s citizens “put up the face”: Dimitri channels his pain into anger at the injustice of “reconciliation”; Wilhelm masks it in shame, and then redoubles through a commitment to peace.

Is this pain useful then? Is it anything? Wilhelm discovers his Ouma’s diary upon returning to Blaas ’n Bietjie, the old family holiday home in the Western Cape. After a while, he stumbles upon her first letter after her husband’s death; reading his grandmother’s pain is an otherworldly experience for Wilhelm, and he struggles with how to reconcile this, how to both “express sorrow and ‘sorry.’”

In the diary, there is a startling entry, dated March 1967:

Last night a peculiar dream. We were at an insane asylum, H. and I. Then a nurse points at a higher floor, from inside and says: “There is the man (the murderer).” I think, "no, how can she say this?" and H. and I half-smile at each other. Then she takes me up many stairs to see him and I realise she knows what she is talking about. When we got to the man where he was sitting working (I think writing), he was just getting up to sort of hand in his work (I think papers): a small, dark little man with long hair — looks like an artist. I wonder whether I should feel I must attack him now over what he’d done, but no, there is no anger or hate or resentment. I wonder if H. would have also felt like this. Actually I know he would have.

The Calatas, too, dream of their dead: Abigail sees a vision of Fort, and relays the message to Nomonde, who interprets it as a sign that he has come back to apologize for leaving her. These posthumous reconciliations are essential parts of the texts, and sometimes it is clear the dead have their purposes in the afterlife. In her speech during the funeral for the Cradock Four, Victoria Mxenge, a human rights lawyer and widow of the murdered attorney Griffiths Mxenge, says: “The dead had gone to deliver messages to the ancestors. […] Go well, peacemakers. Tell your great-grandfathers, we are coming because we are prepared to die for Africa.” Two weeks later, she too would be shot and hacked to death in front of her children at her home in Durban.

And if the Dousemetzis book appears less urgent than the other two on account of its third-person narration, it more than makes up for it with exploration of the despondency felt by Dimitri while incarcerated, abandoned by his mother and sisters as a disgrace to the family. In 1997, filmmaker Liza Key, whose humanizing documentary A Question of Madness (1998) was one of the first to break open the Tsafendas issue, provided a submission to the TRC, concluding:

To some people Tsafendas might seem a monster, a creature beyond human understanding, a Frankenstein. But I would remind you that the power of Mary Shelley’s famous story of Frankenstein lay in the sense of humanity which the monster shared with mankind. I would, as a friend of Tsafendas, like to conclude by quoting the following words of Frankenstein’s monster in Mar[y] Shelley’s novel: “Am I to be thought the only criminal, when all humankind sinned against me?”

In 1999, at the age of 81, Dimitri dies while in psychiatric custody at Sterkfontein Hospital. He is buried in an unmarked grave.

¤

As much as we may want to be separate, to be different from our predecessors, we are made in their image, and they exist within us. Father Paul Verryn writes in the foreword to the Calata book:

There was a point in the celebration when he mounted the stage, and like his great-grandfather and father, made music for the community. His ability to blend into the harmonies made me think that there must be something in the essence of this family that is quite regal in its ability to listen and give of themselves.

It is tempting to leave the story here, to see some families as “destined” for greatness and plumb the histories of their lives for insights and intrigue. Lukhanyo’s father “received his political education […] from a man who would later be described as ‘one of the greatest sons of Africa.’” Both Wilhelm and the Calata men were raised in this context of “greatness” within their communities, with an expectation of great works to come. In this version of the tale, Lukhanyo’s commitment to social justice was a means of honoring his family’s legacy of activism, just as it was for Dimitri an opportunity to do what his father hadn’t, and for Wilhelm, a chance to undo what his grandfather had.

But we know this isn’t the entire story. The men in these works often have fraught relationships with the women in their lives: Fort fathered his son out of wedlock; Tatou was often absent, leaving Miltha to raise the children; Michalis impregnates his housekeeper Amelia, and eventually sends Dimitri away from her to be raised with his new Greek wife; Wilhelm’s father disowns him over the objections of his wife.

In her review of My Father Died for This and other books — including The Resurrection of Winnie Mandela (2018) — Jacqueline Rose writes in the London Review of Books that maybe this is the point, that maybe “the killing of these men can be understood as a sinister type of continuity, enshrining an absence that was already there in these women’s lives.”

Michalis is largely raised by his grandmother, a woman “born in Crete to Greek-Jewish parents,” and comes to see her as one of his most important childhood figures. And the Calata family women are forces to be reckoned with: Miltha, a leader of protests; her daughter, Sis’ Ntsiki, a fighter in her own right; and then there is Nomonde. Nomonde, who leads youth movements in Cradock. Nomonde, who Abigail sees as the “true hero” of the family. Nomonde, who must sit with the grief of her husband’s murder as she raises her three children.

With regards to Wilhelm, the usual criticisms often relate to his positionality: that, regardless of his sincerity and commitment to reconciliation, for him to receive commendation for his politics is a further affront to the work of the thousands who devote their lives to liberation. But this is ultimately reductive — I interviewed Wilhelm before the release of his book, and no one who meets him will make the mistake of thinking he is interested in plaudits. And regardless, what more powerful notice can be appended to the history of Afrikaner nationalism than its repudiation by the sons of its forefathers, the wholesale rejection of its intrinsic racism from within, cast away as the violent ideology that it is?

A fairer criticism perhaps relates to the structure of the nonfiction bildungsroman Wilhelm has built. We are told, that in the same way Cecil Rhodes became synonymous with the most pernicious British colonialism, Verwoerd “became synonymous with apartheid.” And while it is clear Wilhelm understands the pain his grandfather personifies in South Africa, evasive epithets like these can lay the systemic culpability of white and Afrikaner South Africans (for whom apartheid conferred enormous economic and sociopolitical advantages) at the feet of specific individuals. As such, any review of these three works must be careful not to essentialize movements of people down to the stories of their male “heroes.” To do so risks framing African women as silent or apolitical and ignoring their historical and ongoing contributions to resistance.

¤

My Father Died for This takes its darkest turn in its seventh chapter, in which Lukhanyo awakes in the middle of the night to find his father being taken:

When I looked around, the house was packed with police and soldiers carrying these huge guns. They were everywhere. My mom recalled that Dorothy and I woke up, due to the commotion in our tiny two-bedroom home. I asked, “Tata, uyaphi? [Father, where are you going?],” to which he replied, “Ndiyabuya, kwekwe [I’ll be back, my boy],” before they led him out of the room.

This father-son call-and-answer is echoed in various works of resistance poetry and literature. In “The Eternity of Cactus,” the Palestinian poet and revolutionary Mahmoud Darwish writes of a father and son cast away from their homes in Palestine. The poem opens with the son asking, “Where are you taking me, father,” as they leave their home, to which his father responds, “Where the wind takes us, my son…,” reminding him of the land’s long history, and an assurance of a return when the soldiers are eventually worn out by the passage of time. Both Darwish and Calata are recalling a feeling of helplessness, of a father’s displacement by the machinery of the state, and they speak to children’s passivity in the face of their family tumult, always watching, hurting, learning.

The Palestinian experience has long been illustrative for black South Africans who see in it echoes of their own apartheid. And if South Africans, the ANC, and pro-labor groups have taken up solidarity with the Palestinians as an animating cause, then this stems from a belief that pervades the three books in question: that support for the oppressed transcends borders and that stories of intergenerational trauma often repeat. After all, this connection is more than simply mimetic; Sasha Polakow-Suransky writes bracingly in The Unspoken Alliance (2010) of the historical enablement of South Africa’s apartheid regime by Israel’s government. This confers a unique relationship to the Palestinian struggle; Tsafendas was committed to an international liberatory communism, and it is no surprise that Verwoerd, after leaving South Africa for a decade, devoted himself to reconciliation work in Ireland and in Israel-Palestine.

But in the same way Darwish’s vision for the material liberation of the Palestinians has yet to be realized, Lukhanyo must also struggle against a “post”-apartheid reality that does not bring justice to his father. The negotiated settlement that leaves many crimes unpunished is a source of pain and anger for Lukhanyo, who demands to know why the government will not pursue those who killed his father.

It is also a source of rage for Dimitri, who cannot understand the anti-apartheid fighters who themselves ask for amnesty, finding it “absurd that those who had committed violent acts for apartheid and those who had committed violent acts against apartheid were put in the same category,” the latter of which he saw as “acts of resistance against tyrants and thus morally justified.”

In contrast to the other two, Wilhelm is more sanguine, more supportive of the TRC, writing in his book, that he sees it as part of the equation for a more just South Africa. On this, Lukhanyo writes:

My mother was among the first people to testify at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings chaired by Archbishop Desmond Tutu in the East London City Hall in 1996. Author Antjie Krog, who at the time served as a radio reporter for the SABC, would describe the moment my mother was overcome by her emotions during testimony as “an indefinable wail that would become the signature tune” of the TRC hearings.

This is the “one long scream” in Jacqueline Rose’s article, the famous expression of pain that she sees as standing in for any one of the cries of South Africa, of the widows and widowers and martyrs’ children who put on a brave face, who swallowed their hurt for so long, and who let it loose during the long “reconciliation,” in an expression of broken faith.

This idea of a shattered covenant exists in all three books, where religion is often represented with pseudo-physicality — an animating impulse stems from its desecration, just as “the desecration of Fort’s body remains a devastating demolition of the image of God in the life of a person.”

But if all of the three books’ subjects had religious families — Tsafendas was raised as a Greek Orthodox Christian, Wilhelm as a devout member of the Dutch Reformed Church, the Calatas in the Anglican Church — all grow to have very different relationships with their faith.

We are told that Canon James Calata saw his faith as a wellspring from which his compassion for the rights of the dispossessed and his commitment to fighting injustice stemmed. And in a letter to his grandmother, Wilhelm writes of his education abroad as “a time of intense, inner grappling, a protracted crisis of faith, and, eventually, a political distancing from that Verwoerd.”

Wilhelm’s book is littered with biblical passages, and some, like Isaiah 51:1 (“Look to the rock from which you were hewn”), are a bit on the nose. But he becomes “disillusioned with the white Dutch Reformed Church in the mid-Eighties,” largely as a result of its work to entrench and provide theological justification for the apartheid system. Wilhelm keeps his faith in other ways though, seeing in it an inclusionary tradition, but takes care that it remains “a faith commitment to help heal, rather than pass on, collective, historical trauma.”

For Dimitri, his Jewish history — bestowed on the Tsafendas family by his great-grandmother Victoria — affects his worldview, underscoring a revulsion for Verwoerd, who was a virulent antisemite. It also informs an abiding interest in Hebrew history, a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and his courtship of Sarah, a Jewish South African he becomes smitten with, but nevertheless, there is no indication that Tsafendas sees his religion as foundational to his assassination of Verwoerd.

And as much as faith can be a wellspring for activism in the books, the relationship can also be adversarial. In Cradock, the church embodies this duality, serving as a physical place for convening and organizing protest, but also, on occasion, as a collaborator with the state, helping the police identify agitators during the student protests. But it is the individuals within the church who persist, unafraid: when Mrs. Calata is arrested breaking curfew regulations, she leads the Anglican women in a refrain, singing “freedom songs as police marched them into the station.”

¤

When the statue of Cecil Rhodes finally fell at the University of Cape Town, the response from young South Africans was jubilant. Similarly, when the news breaks that Prime Minister Verwoerd has been assassinated, the African nations are, in particular, celebratory: “In Nairobi, the ruling Kenya African National Union characterised the assassination as ‘a symbolic and heartening act, from which millions suffering from apartheid would draw hope.’ In Lagos, many Nigerians shouted ‘Hallelujah’ and danced in the streets.”

This joy is viscerally contrasted in the world of Wilhelm’s family, where his grandfather is seen as having sacrificed his life for the Afrikaner cause. Wilhelm has a complex relationship to mourning in the context of his grandfather. He obviously understands that there is a difference between private remembrance and public honoring, especially when that person represents so much pain to his fellow South Africans. But he sees the public impulse more troublingly, as an additional violence that transcends generations, insofar as it is often framed as a project of “separating” Verwoerd’s legacy as a public servant from his material effects in that role. Both he and black South Africans rightly point out, not only that the two cannot be separated (for the sum total of his life’s work must be seen as the propagation of apartheid), but also that the impulse to memorialize Verwoerd often does not come from some sanitized commitment to honor service, but from a support, or nostalgia, for the program he administered. It is hard to argue with this.

But if it is from this core that we must view efforts to memorialize these “Great Colonialists,” then this perspective from a son of apartheid has implications for a modern approach to historical legacies. Those of us at Oxford University who support the Rhodes Must Fall movement in both its South African and Oxonian incarnations see it as part of a transnational vision of justice. Wilhelm, a Rhodes scholar who supports RMF, believes that it does not “erase” the past to acknowledge the pain that comes from honoring it. He works at Stellenbosch University now, as part of their Historical Trauma and Transformation Unit, and since March has sat next door to Dorothy Calata, Lukhanyo’s older sister. In 2015, he is asked to speak at an event to remove the university’s commemorative plaque honoring his grandfather. Reflecting on this in his book and citing from his speech, he asks:

How do I listen … listen … really listen to the heartbeat of the untransformed pain behind the clenched fists and the bubbling anger of mostly black fellow citizens? How can I play a positive role with regard to deeply rooted, unhealed emotional, moral and soul injuries from our apartheid past?

Sometimes the answer is to hear to what they’re saying. This is the thrust of John Fabian Witt’s article “Slouching Back to Calhoun” in the Yale Daily News. Witt, who chaired Yale’s committee for establishing a set of principles that ultimately led to the renaming of Yale’s Calhoun College — which commemorated John Calhoun, a South Carolina statesman and prominent defender of slavery — says that it is essential to examine the “principal legacies” of figures that have been honored by institutions.

But if this is the case, then what argument is there to not rename the Rhodes scholarships? A distinguished academic and the warden of our Rhodes House, Elizabeth Kiss, has claimed privately, and then publicly in The Times in October, that she and The Rhodes Trust view Cecil Rhodes’s legacy with regards to the Rhodes scholarships as needing to be primarily understood in relation to his work to establish the scholarship, that we risk “running away” from the past otherwise. But one wonders how much historical revisionism it requires to view the “principal legacy” of Cecil Rhodes, a colonial administrator of Zimbabwe, as being the endowment of a scholarship for a few dozen graduate students. One also wonders what the Trust would say to the South Africans who view the “principal legacy” of Hendrik Verwoerd as prosperity, stable leadership, and good governance!

This isn’t always an easy sell. Wilhelm’s two children, who are in their late 20s, struggle to understand why they, as individuals, should pay for the “sins of the father,” the intergenerational questions of responsibility that are as central to South African lives as they are to ours in North America.

But if children imitate their parents — learning from them ways of being in this world, outlooks and hatreds and loves — then what we pass on is essential to this undertaking. Lukhanyo writes about his son, Kwezi, and about these obligations insofar as they are bestowed by his fatherhood:

Although Kwezi’s birth in our flat in Mowbray remains the singular highlight of my life, I was then, and continue to be, daunted by the prospect of fathering him. How do I become the best father I can be when my father was not there to model what fatherhood is for me. My frame of reference for what fatherhood is, is largely pieced together from the odds and ends my mother has relayed to me over the years about the kind of man my father was.

Lukhanyo understands that for reconciliation to be a lifelong project, it must extend past one’s own life, into the lives of those you bring into this world. And on this, the dedication to My Father Died for This is instructive, beginning the book much the way it ends, with an incantation, a summons:

To our son, Kwezi,

and the next generation

of revolutionaries.

¤

Kaleem Hawa is a graduate student and Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University.

LARB Contributor

Kaleem Hawa is a graduate student and Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Mining Nostalgia

An exhibit of apartheid-era photographs by David Goldblatt presents them without adequate context and loses a huge opportunity.

A Relic of Apartheid: Daniel Magaziner’s History of Art Education in South Africa

Alex Lichtenstein reviews Daniel Magaziner's "The Art of Life in South Africa."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!