What Should I Do with Such a Man?: On “Black Spartacus: The Epic Life of Toussaint Louverture”

A new biography does the seemingly impossible: it casts new light on the much-studied founding father of Haiti.

By Adolf AlzupharNovember 26, 2020

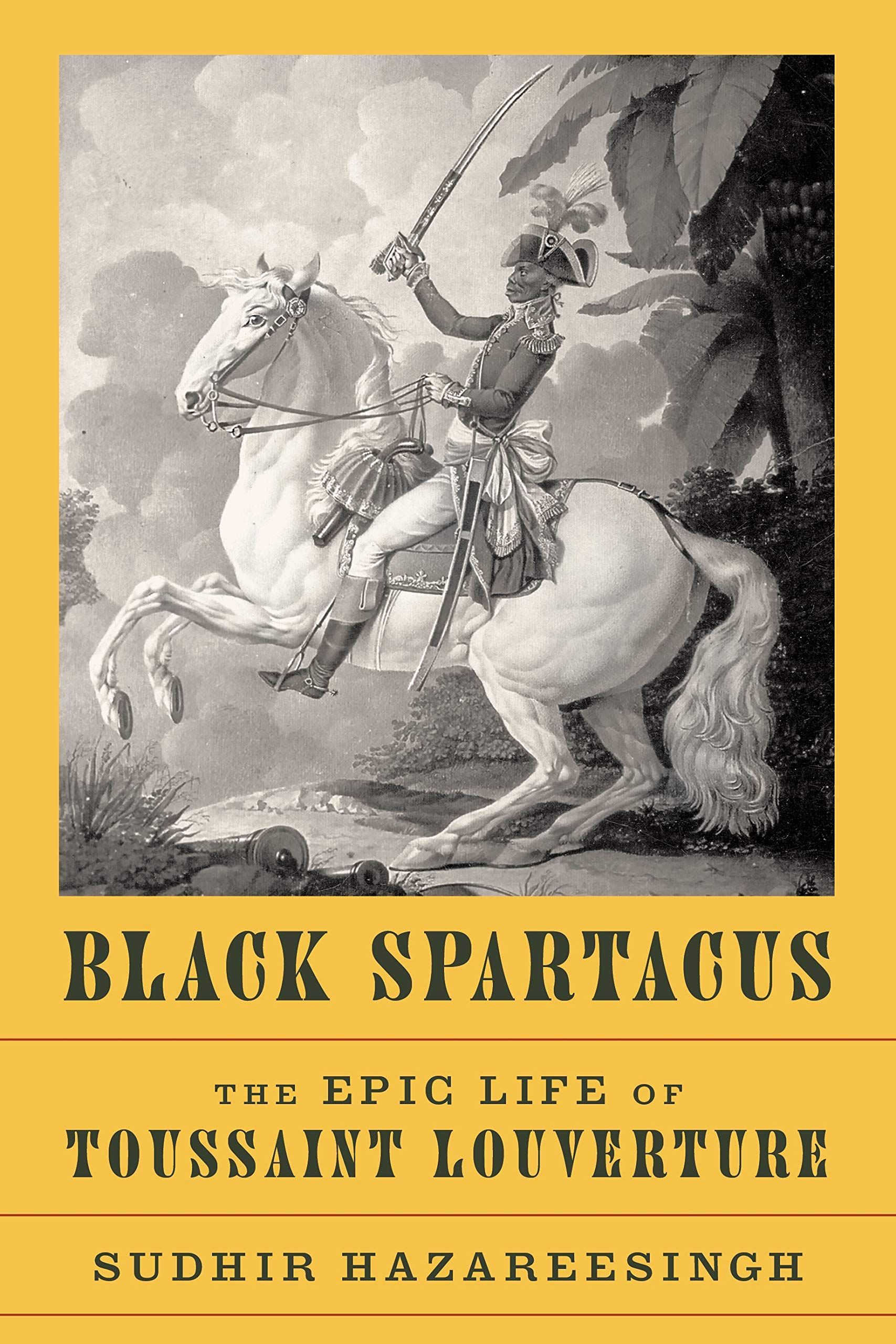

Black Spartacus by Sudhir Hazareesingh. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 464 pages.

IN BLACK SPARTACUS, British-Mauritian writer Sudhir Hazareesingh writes a mesmerizing biography of fellow creole Toussaint Louverture. Out of a morass of archival documents, especially of Toussaint’s own letters, Hazareesingh proves that Toussaint’s life and achievements were not only revolutionary but also compassionate, humane, fraternal, and respected by all communities of his beloved Saint-Domingue (soon to be renamed Haiti), which miraculously included the white plantation owners.

Toussaint’s instincts toward stability may, in fact, have sealed his downfall. A member of Saint-Domingue’s new black elite that he himself created, his reforms of the plantation system favored the white colons. His strict regulations were unpopular. His constitutional independence from France, in which Saint-Domingue was still a colony but had say over its governor-general, meant political and economic independence for his elite who could now be free to pursue regional interests but an affront to France.

Though Saint-Domingue prospered tremendously under Toussaint Louverture as governor-general, its newly emancipated ex-slaves wanted the total abolition of the plantation system. Hazareesingh argues the people of Saint-Domingue wanted less regulation, not more, and certainly not partial “reform.” And France wanted a subdued colony, however prosperous Saint-Domingue could be under Toussaint. These pressures from different directions only made him clench his fist tighter. By his final year in office, Toussaint had become a tyrant to those who had once followed him into battle.

He was born into a relative state of privilege, even while enslaved. At a young age, he became an ardent naturalist, and from this would come the conviction that he was given the soul of a free man by nature. He was a shepherd as a young man, and from this solitude came to not only observe the freedom in the ecology that surrounded him but also the terrain that he lived in, its mountains, rivers, plains, that would serve him well as a general.

He was first a fervent Jesuit, kicked out of the colony for threatening the supremacy of plantation owners, and then a Capuchin, the order that replaced the Jesuits and taught him compassion, humility, and amnesty. From vodou he learned traditional herbalist science as docteur feuilles, and how to communicate politically with fellow blacks (and surely the compassion, humility, and amnesty which can be heard in its songs). His readings, especially Herodotus’s History of the Wars of the Persians against the Greeks, Vegetius’s Scriptores de re militari, Caesar’s Commentaries, d’Orléans’s History of Revolutions in England and Spain, and the inescapable Lives of Plutarch, taught him republicanism. Toussaint became the right-hand man of a white plantation owner Bayon de Libertat. Through this relationship, Toussaint learned not to hate white colons. He also gained his own freedom in 1776.

Hazareesingh writes beautifully about why Toussaint fought for three different sides: rebellious slaves Jean-François and Biassou; the Spanish; and then the French. He built an army but tempered its zeal and installed a white chief of staff, Pierre Agé. What the author called the “Louverturian order” was primarily concerned with fraternal unity of the entire island, including whites. He guaranteed the safety of all persons and properties. Cities such as Môle St. Nicolas, Cap-Haïtien, and Gonaïves flourished as fraternal orders at the hand of administrators that he handpicked. Local assemblies were key to preserving liberty. Black Saint-Domingue, he discovered, had a vibrant democracy and a National Guard that served as a deliberative assembly.

We learn about how Toussaint outmaneuvered every French representative — Laveaux, Sonthonax, Hédouville, Roume — sent to govern the colony. And then he took over the eastern part of the island (today’s Dominican Republic).

Over the coming weeks and months Toussaint threw all his energy into Santo Domingo, introducing a series of sweeping reforms which touched all sectors of public and private activity. He appointed a new keeper of the public archives, reorganized the tribunal of commerce in the capital, brought in new municipal officers, created a corps of gendarmes in every commune (with the important stipulation that each should have a trumpeter), set up public schools, appointed eight public defenders (four in Santo Domingo and four in Santiago), built new roads (notably one connecting Santo Domingo to Laxavon, separated by eighty lieues), and opened six ports to foreign trade, while at the same time lowering taxes and duties so as to attract outside investment.

Toussaint’s diplomacy was a work of art. His subalterns were all white. He found an ally in US President John Adams, who not only chose to supply him but assigned a consul — Edward Stevens — to Haiti. Stevens was given a mission to, among other directives, help Toussaint attain independence for the colony.

The pages on Toussaint’s 1801 constitution illuminate with both the politics and philosophies that shaped the document. Toussaint’s constitutional assembly was presided by Borgella, a white colon and close advisor to Toussaint. The constitution ground itself in republican philosophy, all the while clearly moving away from France’s domination. But then came Toussaint’s downfall, when he was trapped by Napoleon and imprisoned at the Fort de Joux, where he eventually died. Economic order had become his most pressing concern, bringing both wealth and unhappiness to the island. He refused to abolish the plantation system and demanded even more from it:

According to many contemporary observers, the effect of Toussaint’s regulations on agricultural output was immediate, leading to tenfold increases in specific plantations; overall there was a surge in sugar and coffee production, which rose to a third of their 1789 levels by the end of 1801; a year later, cotton exports were up to nearly 60 per cent of their pre-revolutionary levels, and a report to the French government estimated that Toussaint’s revenues from cargo taxes alone were in excess of 20 million francs for 1801. In strictly economic terms, the governor’s plantation system proved to be “remarkably efficient.” But, as we shall soon see, it came at a political cost.

Fraternity broke down. Even his own nephew, Moïse, rebelled against him, and Toussaint ordered him killed. After war with Napoleon, Toussaint himself was captured and exiled to France, but not without prophesying that the tree of liberty has many roots and that the colony could not be subdued.

Was Toussaint a republican? Sudhir Hazareesingh tells us so often, even if the evidence is contradictory. Toussaint did not follow the directives of his superiors and he certainly paid little mind to French law if it got in his way. He was, however, working toward a new republic. His republicanism, however, was grounded not in law but in creole parables such as, “He who receives the blow feels the pain.”

“What should I do with such a man?” Toussaint asked before deciding to hold France’s representative Roume hostage, threatening him until Roume agreed to Toussaint’s plans to take over the eastern part of the island. This question seems to be the one that Toussaint asked throughout his revolutionary life, especially when relating with those who enslaved him.

Sudhir Hazareesingh still persuades us that Toussaint’s decisions were confrontational but fraternal, humane and guided by his love for black people and for Saint-Domingue. As Haitian poet Jeudinema writes, ochan pou laverite ki pa gen klaksonn, which translates to: “Praise be to truth that has no honk.” Ochan for Sudhir Hazareesingh’s Black Spartacus.

¤

LARB Contributor

Adolf Alzuphar is a Haitian human rights activist. He contributes to The Brooklyn Rail and the Los Angeles Review of Books.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Slavery’s End: On Tom Zoellner’s “Island on Fire”

A history of Sharpe’s Rebellion in Jamaica and its role in the abolition of British slavery.

Charisma: Now You’ve Got It, Now You Don’t

A rich and rewarding study of political leadership in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!