What Not to Wear

Bharat Jayram Venkat explores the history of how the business suit became the unit of measurement for heat, in an excerpt from LARB Quarterly, no. 37: Fire.

By Bharat Jayram VenkatMay 28, 2023

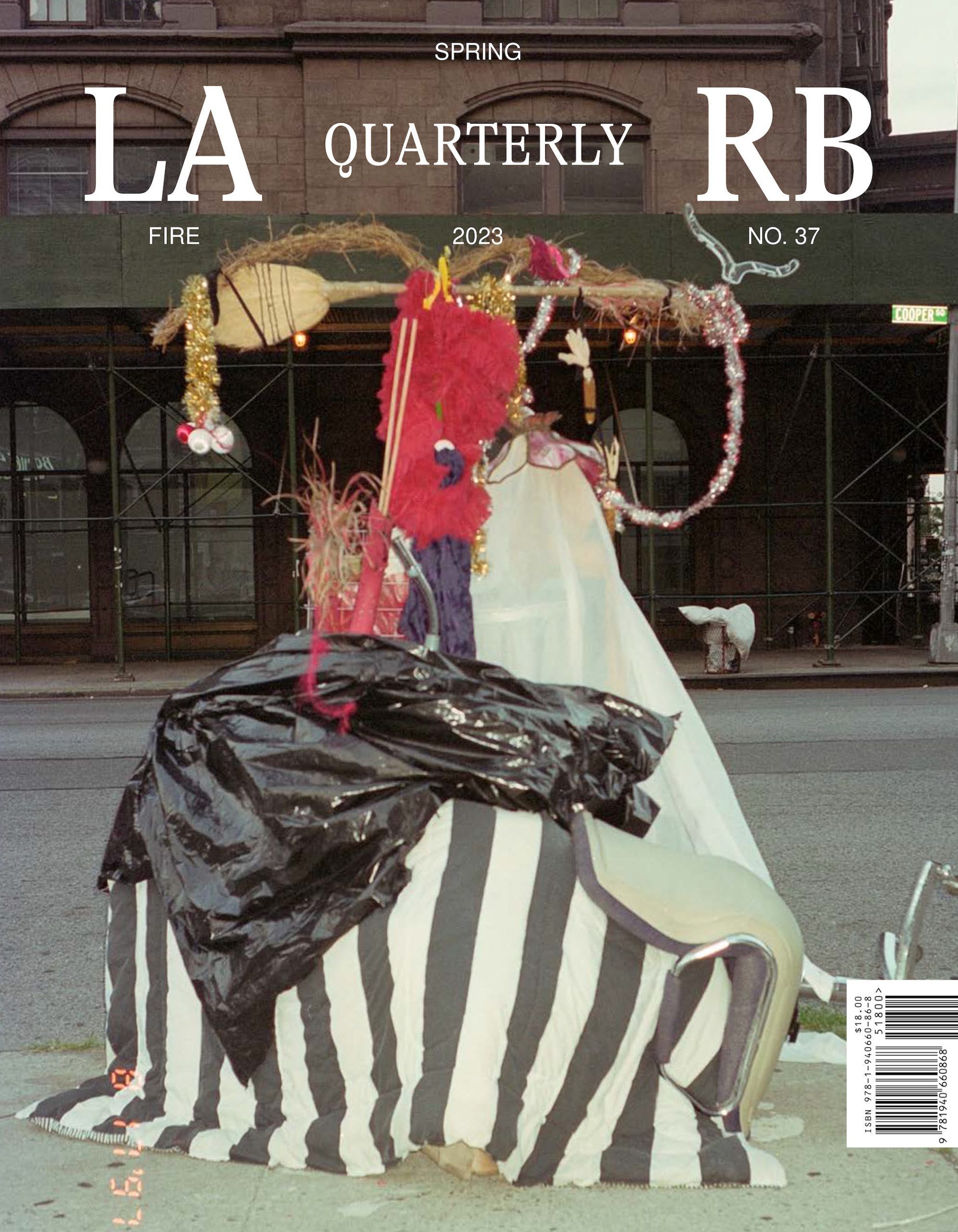

This article is an excerpt from the LARB Quarterly, no. 37: Fire. Subscribe now or order a copy from the LARB shop.

¤

IN THE FALL of 2019, Fiona Hill strode into the Longworth Office Building in Washington, DC, sporting a white blouse and a subdued chain-link necklace peeking out from below a black blazer. Her outfit, in the words of a writer at The Washington Post, was “ferociously, unapologetically dull.”

The dictates of feminist reportage would suggest that there’s nothing so regressive as obsessing over a powerful woman’s clothing choices (see, for example, much of the coverage of Hillary Clinton’s tragically unsuccessful presidential campaign in 2016). That day, Hill had an important job to do: she was to testify before the House Intelligence Committee. Her testimony would be televised, as a fact witness preceding the Senate’s first impeachment trial for then-president Donald Trump. Hill was a Russia expert, and the former senior director for Europe and Russia at the National Security Council; her words would undercut the right-wing narrative of Ukrainian meddling and point instead to the Kremlin’s investment in sowing discord in American politics, despite Trump’s claims to the contrary.

In the days leading up to her testimony, Hill met not only with her lawyers but also with a media consultant named Molly Levinson, known as a top crisis counselor, problem solver, and reputation manager. The stakes were high: everything Hill said (and didn’t say) would be dissected and analyzed. But Levinson’s concerns extended beyond what Hill said to what she wore.

“Molly knew the congressional hearing room well.” Hill wrote in her memoir. “The air conditioning was cranked up and the temperature set low to accommodate congressmen in their layers of undershirts, dress shirts, and suit jackets so there would be no risk of sweaty armpits and brows beaded with perspiration.” Levinson warned “that as a more lightly dressed woman, [Hill] risked freezing.”

To effectively transmit the seriousness of her message to the viewers at home, Hill could not appear cold. Levinson made Hill practice grinding the balls of her feet into the ground to prevent shivering. She also counseled Hill to wear pantyhose to hide the goose bumps that might emerge as her body responded to the chilled congressional hearing room (based on available photos, it’s difficult to gauge whether she followed this particular piece of advice). What Levinson offered was something like a finishing school for women in politics; rather than learning to stay afloat atop their heels, women now had to learn how to push their feet into the floor.

To the American public witnessing Hill’s testimony from the comfort of their homes, an involuntary shiver, as easily as a perspiring brow, might read as a sign of dishonesty. It was not only Hill’s reputation that was under threat but also her message: according to her testimony, Hill wanted to communicate nothing less than the “peril that […] we were in as a democracy.”

The emergence of mechanical air conditioning in the early 20th century made it possible to control thermal conditions on a previously unfathomable scale, ensuring that vaccines preserved their potency, bananas ripened at just the right time, and congressmen avoided unsightly pit stains. As the world outside became hotter—a reflection of our impending climate catastrophe—our interior worlds became colder. But the creep of climate control technology into nearly every aspect of our lives is only part of the story. What was also needed was a whole series of developments in the measurement of heat and its effects. Why, for example, did the business suit become the standardized unit for measuring how heat infiltrated the clothed body? And how could you safely study the impact of extreme heat without killing your test subjects?

¤

These questions began to find answers at the height of the Second World War. About as far away from the front as you could get, a physiologist named Harwood Belding—Woody to his friends and colleagues—sat in a basement at Harvard University. There, he grafted together his own contribution to the war effort out of sheet metal and stovepipes. Belding was employed as a civilian scientist working for the US Army as part of Harvard’s Fatigue Lab.

The Fatigue Lab was a critical site for the study of exercise physiology, labor, and adaptation to extreme conditions, including both temperature and altitude—in other words, conditions that went far beyond what might be narrowly defined as fatigue. The Lab was established in 1927, in the basement of the newly constructed Morgan Hall (named after the financier J. P. Morgan) at Harvard Business School, and ran for two decades. Test subjects included not only soldiers but also sharecroppers, miners, workers at the Hoover Dam, Olympic athletes, and even the scientists themselves (self-experimentation was far more acceptable in those days).

At the Fatigue Lab, Belding tested clothing and equipment for both the army and industry on human volunteers. The army had heavily financed Belding’s research, in the hopes that his findings could help fortify American soldiers against heat-related illnesses like stroke and fatigue as well as cold-related conditions like trench foot and frostbite. Soldiers were offered up to uncomfortable thermal conditions, had their vitals taken and their comfort levels questioned. But humans, it turned out, were unreliable narrators of their own experiences. The same soldier, subjected to the same conditions, might provide a different response the second time around. Moreover, the soldiers kept passing out under extreme heat conditions, which was both inconvenient for researchers and undoubtedly unpleasant for the soldiers themselves.

Inspired by a mannequin that he saw in a department store window, Belding’s solution to these problems was to construct what he called a manikin: a headless and armless automaton complete with an internal heating unit and a fan to distribute heat throughout its metal body. Manikins were built to emulate specific physiological functions of the human body; in this case, to sense heat. Two years later, Belding refined his rudimentary design with engineers at General Electric to build an electroplated, copper-skinned manikin transected by a single electrical circuit. The various parts of the “Harvard Copper Man,” as he came to be called, were created using clay molds produced by the Connecticut-based sculptor Leopold Schmidt. The measurements for these manikins were based on anthropometric measurements taken of male army recruits.

Thermal manikins could also be fitted with clothing, which allowed researchers to test how the things we wear mediate thermal sensation and comfort. Given that most humans are nearly always wearing some kind of clothing (except for when we’re bathing or making love), the effect of various textiles and layers on how we experience heat was and has remained an important thing to study—especially given that clothing (taking it off, putting it on, changing it) represents a straightforward way of adjusting our thermal conditions.

Though hardly fashionable as a group, thermal researchers nevertheless became highly sought out as clothing designers. The Yale-trained physicist Adolf Pharo Gagge, for example, helped to redesign the outfits worn by Air Force pilots, initiating a shift from the use of natural fibers to artificial materials that better maintained thermal comfort as aviators navigated intense atmospheric conditions. Gagge’s expertise was in physics; he served as chief of biophysics at the Aeromedical Laboratory at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, then at the Human Factors Division Directorate (also in the Air Force), and finally, as manager of what was rather sinisterly described as “cloud physics and weather modification” for the Secretary of Defense.

Around the same time that Belding was experimenting with his manikins, Gagge developed a unit for measuring thermal insulation that he called the clo. After acquiring his own manikin from General Electric, Gagge began to assess the insulative properties of a range of clothing ensembles. One clo was standardized as the insulation provided by a business suit and cotton underwear. By contrast, pantyhose only provided .01 clo, and a long-sleeved T-shirt and tie provided .29 clo.

Gagge’s use of the business suit as the standard measure for insulation was deliberate: to his mind, it was familiar to the general public and therefore a readily available reference. But while the figure of the suit-clad 1940s human might have been widely recognized—similar to the way that we might all recognize a firefighter or police officer—it only represented a very small portion of American society: one that was predominantly male, white, and white-collar.

So now we’re finally back to the business suit and the pantyhose. And we only have to think back to Fiona Hill’s description of preparing herself to testify before the House Intelligence Committee to understand how Gagge’s research shaped the climate of Congress—a climate built for a man in a suit, or more precisely, a manikin in a suit.

The clo was developed as a tool for better understanding thermal conditions and increasing comfort. Yet, the decision to take the business suit as the fundamental unit for insulation resulted in the standardization of thermal conditions that made certain kinds of bodies comfortable at the expense of others.

¤

In the early 1960s, Cold War anxieties about chemical warfare provided a new stimulus to thermal manikin research. The Soviets and their allies, it was feared, had built large warehouses stockpiled with chemical munitions. During World War II, the US armed forces had developed certain forms of protective clothing. But the effectiveness of troops while wearing this complicated and heavy outfit—which included a gas mask, long underwear, a buttoned-up combat uniform, cotton gauntlets, long socks, and a rubberized overboot on top of standard combat boots—was questionable. Experiments conducted with soldiers in climate-controlled chambers revealed that at high temperatures, the thermal conditions produced by wearing this complicated outfit could actually kill troops more quickly than chemical exposure. Manikins were once again utilized in an effort to develop lightweight materials that might offer chemical protection while avoiding overheating.

I was reminded of this Cold War research in July of 2022. While doomscrolling through my social media feeds, I came across a photograph of Chinese health workers encased in biohazard suits, delivering COVID-19 tests in the midst of a prolonged heatwave. The suits were meant to protect the health workers from infection. But they also caused them to overheat. A friend who worked in Sierra Leone during the recent Ebola epidemic described a similar dynamic, where suited-up doctors and nurses began to suffer from heatstroke in the midst of their long shifts. To avoid this fate, these Chinese health workers had taped popsicles (the ones that come in plastic wrappers) to their suits. They hoped that these frozen desserts would cool them down; a bit of cold comfort, indeed.

¤

LARB Contributor

Bharat Jayram Venkat is an assistant professor at UCLA’s Institute for Society & Genetics, with a joint appointment in the Department of History. He is the author of At the Limits of Cure (Duke University Press, 2021), winner of the Joseph W. Elder Prize in the Indian Social Sciences. He is also the director of the UCLA Heat Lab.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Thinking in Ruins: On the Llano del Rio Experiment

In a preview of LARB Quarterly's upcoming issue, Earth, Laura Nelson explores the Llano del Rio failed commune experiment in the California desert.

“Sir, You Do Realize I Am 9-1-1?”: On the Lives and Afterlives of California’s Firefighters

Jaime Lowe reports on the neglect and exploitation coursing through the civilian fire infrastructure revealed after the release of her book “Breathing...

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!