“Sir, You Do Realize I Am 9-1-1?”: On the Lives and Afterlives of California’s Firefighters

Jaime Lowe reports on the neglect and exploitation coursing through the civilian fire infrastructure revealed after the release of her book “Breathing Fire,” which investigated Shawna Jones’s life and her death—and the stories of the more than 200 women who worked on all-female crews as part of California’s incarcerated firefighting system.

By Jaime LoweMay 1, 2023

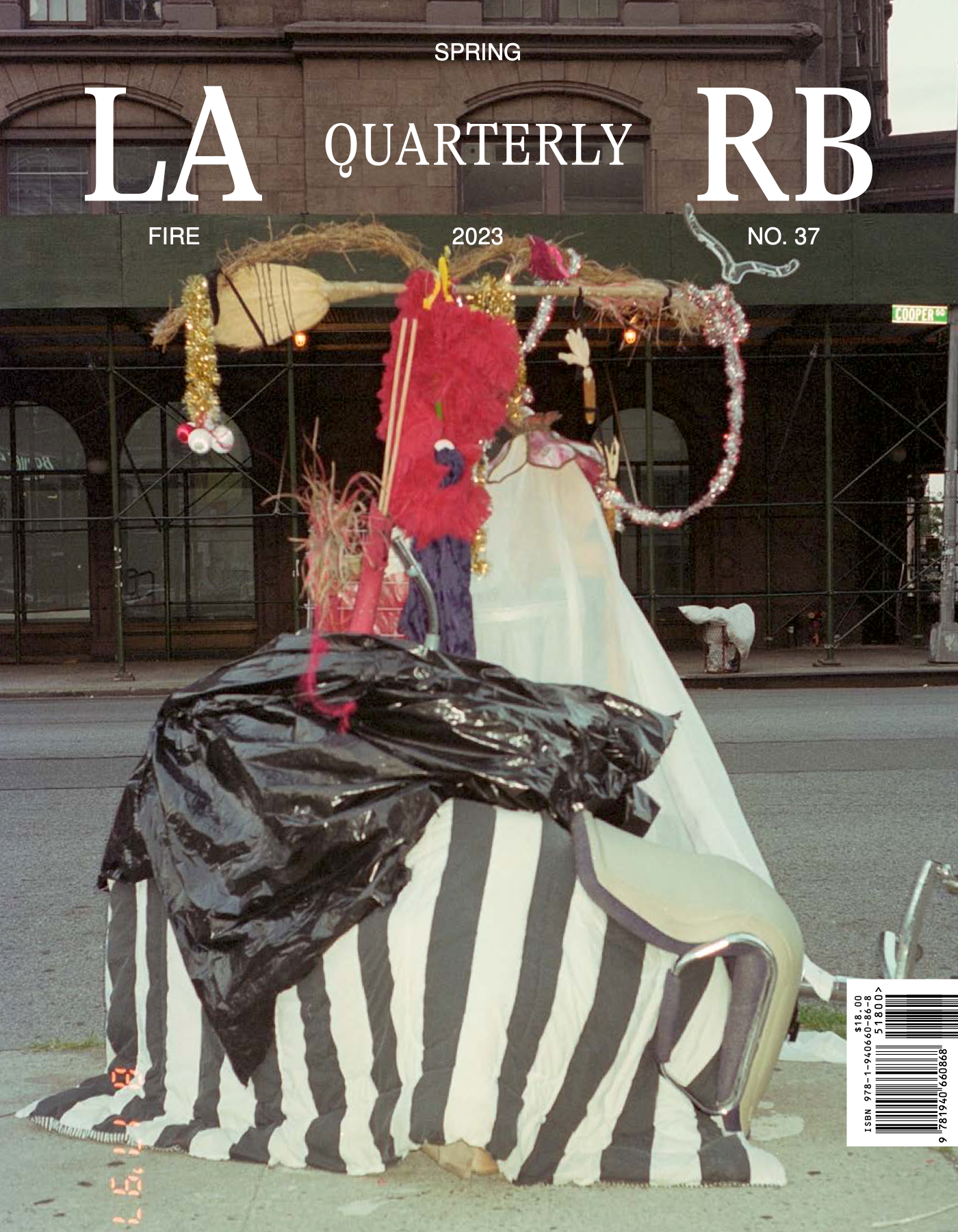

This article is a preview of The LARB Quarterly, no. 37: Fire. Preorder from the LARB shop.

¤

SHAWNA LYNN JONES was 22 years old when she was dispatched to fight the roughly 10-acre Mulholland Fire from conservation camp Malibu 13. It was February 25, 2016, and after serving eight months following a probation violation from a 2014 drug charge, Shawna was only three weeks shy of her release date. She and her incarcerated crew—13-3—were first to arrive on scene. This was not like their usual assignments—maintaining Malibu fire roads for multi-million-dollar estates and ranches. This was an actual fire. They hiked in, cut line, and worked through the night and early morning to put out the flames. By dawn, the catastrophic event was not the fire; it was that Shawna had been struck by a boulder and lay lifeless on a steep incline of the Santa Monica mountains.

In my book Breathing Fire, I investigated Shawna’s life and her death—and the stories of the more than 200 women who worked on all-female crews as part of California’s incarcerated firefighting system. Since the book came out, I have given countless talks and lectures. What I repeat over and over is something I’ve learned from people in the field: firefighting is one of the most physically and mentally demanding jobs. Doing it while incarcerated is nearly impossible. Incarcerated fire crews aren’t just responsible for fire. They respond to mudslides, floods, blizzards and, as recently as February, were tasked with shoveling and clearing snow in the San Bernardino mountains for stranded residents. They are on the front lines of the climate crisis. One of the many differences between civilian crews and incarcerated crews is that, after protecting California’s wildlands and neighborhoods built in high-risk fire zones, incarcerated crews return to the status of state prisoners: they’re confined to camp, monitored, and reprimanded by corrections officers. The women, and thousands of men, who make up incarcerated crews work for dollars a day. Upon release, they’re largely forgotten.

What started as a portrait of Shawna Lynn Jones, whose death shocked me, grew into an investigation of California’s prison system, its fire fighting brigades, and personal histories of the women who knew Shawna and the system that killed her. I wanted Shawna to be recognized by the community she served. I wanted people outside of the prison system and beyond her immediate family to know who she was and what she did: that she wanted to join the forestry service when she was released; that she had an absurdist sense of humor; that she skateboarded throughout the Antelope Valley; that she loved her mom; that she rescued puppies and stole food for them; that she was a whole person, more than just her sentence. I wanted to write about Shawna Lynn Jones because I wanted to give her an afterlife.

Books are fixed objects, but they, too, have an afterlife. Because of the book, I talk regularly with those who were in the incarcerated firefighting program and people who are imprisoned. They hear me on the radio or TV. If they’re incarcerated, it’s harder to get the book—hardcovers aren’t allowed in prison because California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) believes that they can be used as weapons. But my book has continued to circulate through the firefighting community. Last year I got an email from a man named Jason Hodge who, for roughly 20 years, had worked for the Ventura County Fire Department and as management on large-scale incidents as a Federal Wildlands Firefighter. The subject of his email was “Shawna Lynn Jones.”

When Hodge wrote to me, it had been six years since Jones died. There was still no official resolution about Jones’s death from the Los Angeles County Fire Department, Ventura County Fire, Cal Fire, or CDCR. Several women who were at the scene had told me there was another crew above them and that, even though the fire was contained and relatively small, rocks and loose soil fell on them from above. A falling boulder fatally struck Jones in the head. Her mom, Diana Baez, received no compensation from the state because it didn’t consider Jones a firefighter.

“First off, I believe her death was our fault,” Hodge wrote in an email to me. He and his crew of civilian firefighters were “careless and arrogant” because it was a small fire in February with no drought conditions. From that day forward, Hodge continued, his “life’s been a bit of a nightmare. A lot of it is still very raw to me. I’ve also spent years trying to get basic help from my department and it’s failed me miserably.” He included his phone number and said he wanted to talk. I wanted to hear his perspective—that of a civilian firefighter. Most aren’t willing to share details of deaths like Shawna’s. In searching for answers about her death and about why and how the incarcerated fire camps existed, I also found neglect and exploitation coursing through the civilian fire infrastructure. One of the women I profiled whose firefighting career started at Malibu 13 ended up on a Hotshot crew, and then on Helitack crew. As part of the federal brigades, her status was classified as seasonal. She had no job security, health insurance, or pension. Just last year, the Biden-Harris administration raised the minimum wage of federal wildland firefighters to $15 an hour.

Last June, CalMatters, a nonprofit news organization that focuses on California, released a four-part investigation into Cal Fire and mental health. In it, they found that, “with too few firefighters to cover all the fires, firefighters are on the front lines longer, with shorter respites at home. Some battle fires for months at a time.” The report included accounts from fire station leaders who are witnessing an unaddressed epidemic of PTSD and suicidal thoughts among their crews. Cal Fire does not collect any data on suicide or PTSD within its ranks and never has, despite having ample reason to. Firefighters are 40 percent more likely to take their own lives than the general population; in another study conducted in 2019, co-authored by former federal firefighter Patricia O’Brien, of more than 2,600 wildland firefighters surveyed, about a third reported experiencing suicidal thoughts; and nearly 40 percent said they had colleagues who had committed suicide.

When I called him, Hodge was forthcoming about his condition. He told me that he experienced suicidal ideation regularly. “They finally got me diagnosed with moderate to severe PTSD,” he said. “I started taking medication.” But, he explained, he has to pay out-of-pocket for psychiatric care.

He’d just gotten back from three weeks doing fire logistics in New Mexico and said that he was aware of the risks he was taking in talking on the record about his situation. He knew that he could have stayed silent, worked two more years, and retired. He feared losing relationships within the field and opportunities for advancement in his career. “You’re always afraid there will be repercussions,” Hodge said. He told me he wants to continue working fire long after he retires, but that he feared he wouldn’t be allowed to because of the stigma attached to mental health issues. Firefighters have long cultivated an air of stoicism. But a combination of fatigue, intensifying fires, and increasing workloads have left many crews understaffed. “Then it would have been the same for everyone else, and I’m just sick of us failing ourselves,” Hodge said. “Our world has changed, and we have not changed with it. The stress is going to get higher, and it’s going to get worse before it gets better.”

Hodge needed someone to talk to about the day Jones died. He described the still-smoldering mountains—stumps and roots glowing orange. He was standing a few feet above Shawna and three of the women on Shawna’s crew, joking with them. Hodge noticed another crew 20 feet up the mountain. “I had no idea who was up there. But they kept knocking rocks loose. And so, there were small rocks falling, and someone says on the radio to be careful because someone’s working up top. Well, first off, that’s fucking negligence,” Hodge said. He heard a crack, the sound of the boulder hitting Shawna’s helmet; then screaming, the sound of her crew’s reaction. “I ran down and Shawna had fallen somewhat down the hillside when it hit her. And then me and the other inmate, we both pulled her up and started cutting her gear off to do CPR. And as soon as I felt her head, I knew it was bad. I knew her skull was broken.”

Hodge told me that, after they had witnessed Jones’s death, the department “didn’t bother to put us out of service.” For some firefighters, trauma is a result of a single incident; for others, it’s an accumulation of a lifetime of service. For Hodge, it seemed to be both. “I do see five or six big fires a year. And I like it. And I want to keep doing it for a long time, even after I retire. But the system itself prevents me from healing at this point,” Hodge said. He told me about how he ignored symptoms of PTSD after Jones’s death—he was claustrophobic, he couldn’t get an MRI because of the tight enclosure, and after a lifetime of surfing, he could no longer swim with his head underwater. “I just couldn’t find a lot of peace in my mind,” he said. Every now and then, he searched Jones’s name and didn’t see any lawsuits or follow-up. “It was a fire in February, which we weren’t expecting, and we weren’t taking it seriously.” He went on: “At least if it was me who got killed, my wife would get a quarter million dollars or something.”

Two years after Jones’s death, Hodge was on a similar emergency response in which he administered CPR to a woman who suffered similar injuries to Jones. She also died. “I grabbed her head, and as soon as I did, the back of my fingers just went into her skull. And it’s the same thing that happened with Shawna, I had the exact same feeling,” Hodge said. It instantly took him back to the Mulholland Fire and Jones’s death. He called in sick; drove six and a half hours home to his wife in San Francisco; canceled his next shift; tried to drive back to Ventura but couldn’t bring himself to start his truck. “I had a panic attack,” he said. Hodge called the Employee Assistance Program, a counseling hotline for county workers. According to Hodge, when he first called, no one answered. He left messages. No one returned his call. When he did get through, the person on the other end of the line told him that the first available appointment was in four to six weeks. When Hodge told the operator he was suicidal, the operator suggested he call 9-1-1. “Sir, you do realize I am 9-1-1?” Hodge said. “Those are the last people I wanted to see.” That’s part of the problem, Hodge explained. The state’s strategy in dealing with the mental well-being of its firefighting brigade is to rely on peer counseling. “You don’t want to tell the guys that you work with that you’re going crazy,” Hodge said. “You feel so pathetic. You feel like you failed.”

Hodge knows that climate catastrophe means fires will only become more frequent, bigger, and more intense, and fire agencies—municipal, state, and federal—are unprepared. California’s worst fire season on record was 2020, with more than 8,600 blazes taking 33 lives and burning four percent of the state. Megafires have been replaced by million-acre “gigafires.” The United Nations estimated that highly devastating fires worldwide could increase by 57 percent by the end of the century. “We’re still putting Band-Aids on,” Hodge said. The department, according to Hodge, hands people in crisis stacks of paperwork and routinely denies Workers’ Comp claims, especially ones rooted in mental health. “The county told me to download a form for an injury—which, when you read it, asks what caused the injury. For example, ‘struck against concrete.’ Then it asks you how you can avoid this injury which at that point …” He trailed off sounding frustrated all over again. Hodge recognizes that he works for one of the better fire departments in the country and yet he still can’t get the help he needs. He said that he likes being a firefighter—friends and relatives call him a hero—but in reality, he added, “I just have the best seats for the apocalypse.”

When Shawna was riding in the fire buggy to the Mulholland Fire, she had just started to train as a sawyer, the lead position on crew responsible for holding the chainsaw and cutting branches and growth to create the containment line. She had asked her captain to train as a sawyer so that, when she was released, she could list the experience when applying for forestry jobs. Being a sawyer is the hardest position on crew because of the weight of the chainsaw and because each cut creates a path for the crew to hike. As the bus wound its way up the circuitous mountain roads, Shawna turned to her crewmate and said she was scared. She had never seen fire before.

¤

LARB Contributor

Jaime Lowe is the author of Breathing Fire: Female Inmate Firefighters on the Front Lines of California’s Wildfires (2021), Mental: Lithium, Love, and Losing My Mind (2017), and Digging for Dirt: The Life and Death of ODB (2008). She is also a contributor to The New York Times Magazine.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Universe’s Couch: A Conversation Between Bud Smith and Mike Jeffrey

Bud Smith and Mike Jeffrey discuss their semi-autobiographical fiction in the forthcoming “Fire” issue of “The LA RB Quarterly.”

The Water’s Edge: On Laura Aguilar’s Photography

Rosa Boshier González on Laura Aguilar’s Los Angeles from The LARB Quarterly, no. 36: “Are you content?”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!