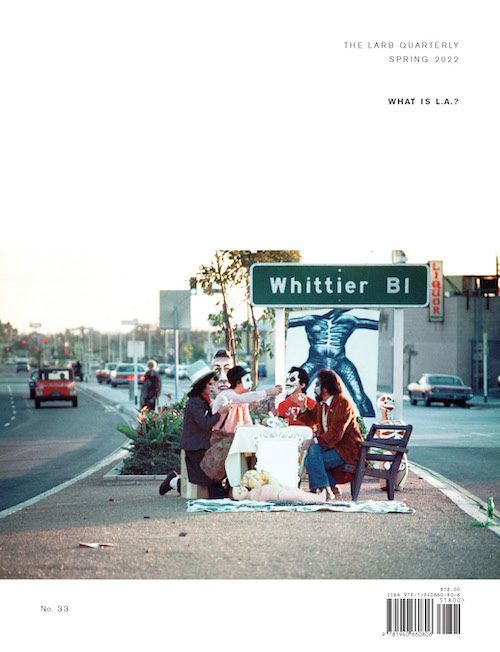

What Is L.A. Art?

Perwana Nazif on Suzanne Jackson and the character of L.A. art.

By Perwana NazifMay 8, 2022

This essay is a preview of The LARB Quarterly, no. 33: “What Is L.A.?” Available now at the LARB shop.

¤

TO ARTICULATE AN L.A. art ethos is counter to the ephemeral, decentered nature of the city itself, its fiction-making and philosophizing. The specificity of L.A. art involves a sprawl: from the pedagogical experimentations of CalArts’s heyday, to car-level murals blanketing the city, to the perceived lack of effective communal infrastructure that leads to art shows in the backyards of bungalows, closets, under freeway passes, dining rooms, alleys, basketball courts, garage entryways, neighborhood parks, old Western movie sets, motel rooms, hotel rooms, living rooms, warehouses. The list of art spaces in L.A. is exhaustive and, increasingly so, a “who owns” as opposed to “who’s who” in its renegotiations (and reproductions) of public-private taxonomies. Still, the spontaneity circumvented by the lack of heavy pedestrian traffic in Los Angeles is made up for by perpetual innovation. The through-line in Los Angeles art culture — from the capitalized, to the nostalgic, to the necrophiliac, to the golden-bathed, guava-splattered punctum in the sea of all that — is improvisation.

The stillness in L.A., its relentlessly sunny monotony, spawns anonymity. Strip malls, carpeted bars, the intimacy in moving vehicles’ windows, echo through the city’s built and affective infrastructures. If ever there were some way to articulate an L.A. ethos, the artists in the following portfolio certainly express it: they articulate the sentiment of plastic possibility. The range of works presented here, heterogeneous in medium, content, form, and process, refract the fixed and fixing parameters of L.A. and its art.

Suzanne Jackson:

Suzanne Jackson opened Gallery 32 in unit 32 of the Granada Buildings at 672 North Lafayette Park Place in 1969. With a name that referenced the numbering of Alfred Stieglitz’s Gallery 291, which was a meeting and educational exhibition space for avant-garde ideas, Gallery 32 was among few exhibition spaces that actively supported Los Angeles’s emerging Black artists at the time — although not exclusively. A space indicative of its time, when live-work-exhibition spaces were not unusual and affordable in Los Angeles, Jackson’s Gallery 32 set a precedent for what an official gallery could do in its openness to less formalized delineations, which allowed it to occupy myriad forms simultaneously and genuinely. Its pliancy generated an active and potent public.

Gallery 32 was a site of fecund experimentation, welcoming readings, fundraisers for organizations such as the Black Arts Council, Watts Towers Art Center, and the Black Panther Party, and performances, dinners, and discussions with Jackson’s community of artists, including Senga Nengudi, David Hammons, and John Outterbridge. Encompassing the social, political, the spiritual, and questions of Black aesthetic(s) of that particular moment, debates at Gallery 32 were not exclusive to after-dinner talk. A treasure of archival ephemera — announcements, images, mailings, and posters — renders palpable the gallery’s meditations on the community it enacted.

Its traces linger, like the layers of salvaged material found in Jackson’s most recent suspended acrylic works, which hybridize painting and sculpture, and often incorporate found organic matter. Jackson’s work reminds us of that very real possibility of decomposing into the earth, not unlike how the closure of Gallery 32 in 1970 gave way to something other than the “end” — something remained there decomposed, deconstructed, fertilizing the future in both spiritual and earthly ways. Los Angeles art gallery O-Town House, located in the same Granada Buildings, paid homage to Gallery 32 in Jackson’s solo exhibition there in 2019, while Jackson’s New York gallery, Ortuzar Projects, last summer revisited the landmark Gallery 32 exhibition Sapphire Show, spearheaded by Betye Saar in 1970. The original show, which included Jackson along with Gloria Bohanon, Betye Saar, Senga Nengudi (then known as Sue Irons), Yvonne Cole Meo, and Eileen Nelson (then Eileen Abdulrashid), was the first survey of African American women artists in Los Angeles. These contemporary iterations affirm not only the historical precedent, but also, and equally importantly, the regenerative power in Jackson’s curatorial and artistic practice.

To that point, Gallery 32 was not a “blank canvas” white-walled gallery space that would pontifically employ the radical in name only — its social and political engagements were active and material. Such was the reality of the racial violence that the gallery’s association with fine art did not protect it: Jackson and the artists she worked with were often targeted by police, and the FBI regularly visited the gallery after a three-day exhibition of Emory Douglas’s work hosted by the Southern California chapter of the Black Panther Party. The ever-present threat of state violence in response to (and in anticipation of) art surfaces in a very different politics of experimentation, and of the identification of the revolutionary from the conventionally touted experimental art scene in Los Angeles. The potency of Jackson’s practice preceded and exceeded the vitality of the aesthetic forms she presented.

Not that Gallery 32’s artists and audiences were always exclusively or explicitly politically active. The gallery was located at the nexus of several neighborhoods in Los Angeles, many of which were not immediately connected to fine art per se, and Jackson’s background in dance and theater drew diverse crowds of visitors to the often-packed opening nights. She reached further-flung patrons by mailing gallery announcements to names and addresses she found in local newspapers’ celebrity columns.

This ethos of pointed inclusivity is reflected in Jackson’s own artworks. Her suspended painting fly away mist (2021), composed of acrylic, acrylic detritus, produce bag netting, carpet edging, laundry lint, and D-rings, offers a wide spectrum of reds from purple and brown to yellow, separate and mixed. Its wayward rounded form and reds read into the experimentation of its assemblage-like nature. Then, to be Alone (2018) drapes over a long cylindrical rod to create a cascading shape. The painting’s translucency is increasingly made opaque with color and traces of color as one moves down the work. The overall work, then, forms the image of paint itself, suspended in the process of its making. Each suspended abstraction welcomes a rush of questions: Is it floating? Is it grounded by its suspension? Is it heavy or is it purely buoyant? Is it spiritual and ancestral, or rooted in material, in an earthiness? Is its improvisation limitless or is its freedom born of its knowledge of constraints? The answer being, of course, yes to all simultaneously.

The possibility of change (over time with slight contraction or expansion, outside forces that could sway the work) and the capacity granted to view Jackson’s paintings from below, from one side to another, to the edge and beyond, reiterate the ever-perpetuating nature Jackson generously seeded more than 50 years ago at Gallery 32.

¤

LARB Contributor

Perwana Nazif is an independent writer and curator in addition to her work as the art director for the Los Angeles Review of Books. Her essays, interviews, and reviews have appeared in The Quietus, Artforum, SFAQ, and the Vinyl Factory, among others.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!