“What Is Emerging”: On Jana Prikryl’s “Midwood”

Nathan Blansett considers “Midwood,” a new collection of poems by Jana Prikryl.

By Nathan BlansettAugust 31, 2022

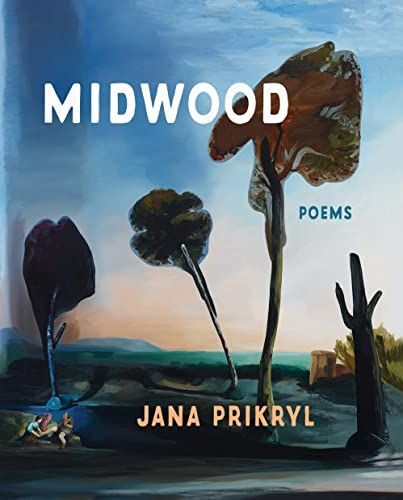

Midwood by Jana Prikryl. W. W. Norton & Company. 128 pages.

BECAUSE “THE LYF SO SHORT, the craft so long to lerne,” as Chaucer observed, it’s all the more impressive that the poet Jana Prikryl has published three books in the last six years — and that her most recent, Midwood, makes clear and unmistakable the increasing singularity of her artistry.

Many of us admire Prikryl for her work as executive editor of The New York Review of Books. She was born in the former Czechoslovakia, raised in Ontario, and lives in New York City. Her first book debuted rather nonchalantly; its title, fittingly, is The After Party (2016). Its guest list is erudite and eclectic: celebrities and semioticians alike make extended appearances. These poems proceed with an insouciant, therefore charming etiquette (“How calmly you indulge my moods”); they have up their sleeve a sleek and adventurous and riveting sense of that thing many poets don’t even presume to attend to anymore: enjambment. But it is the presence of a brother deceased 20 years that provides an emotional magnet.

When our speaker receives, at the end of the first section, a never-not-interesting piece of advice (“look the other way”), she takes note, and the archipelagic long poem that makes up the entirety of the book’s second half gradually discloses the considerable range of Prikryl’s lyric intelligence. How can a book ushered forward by a clever and aristocratic naughtiness of tone end with lines of such irenic and sated beauty, on a wordless and etherizing image of “each pine / […] expressing its individual silence”? It is a move that renders The After Party — in Hopkins’s terms — counter, original, spare, and earnestly strange. Though a fair number of poems betray too fond an admiration for John Ashbery, the book holds its own.

The abundance of run-on titles in No Matter (2019), Prikryl’s second book, has the effect of dropping us into the thick of things, into the pulverizing thrall of the metropolis, into a cityscape seemingly “soaked with dark water repeatedly and repeatedly wrung out.” A gust of wind blowing up the street is memorably “the one voice just stating the obvious.” The weakest here, as in The After Party, are crushed by overreliance on conceit. Just as many of them exude dramatic and enormous beauty.

With a beguiling front cover to boot (a Fauvist-inspired canvas by the painter Emma Webster), Prikryl’s latest shoots off at breakneck speed. Near the beginning of Midwood, the speaker of “Fence Post,” having witnessed “a train that collided with a convoy / of trucks,” observes “each vehicle and each car interlocking at precisely the right moment / like gears in a fine piece of machinery” — a chance occurrence, not unlike the spectacular collision and congruence of the various and disparate elements of a lyric poem. But our poet keeps looking:

so they went through each other, the train and the convoy,

it took some time for them

to move through each other and then each went its own way

What we witness is a near-collision, a near-meeting of parts — but not quite. The poet is filling us in on how, exactly, her lines are going to behave around and among one another; she is describing how, exactly, her lyrics may always “resist the intelligence / Almost successfully” (Wallace Stevens).

In “Our Second,” the seaside speaker looks closely at “a closed current / as small as a necklace.” Separated from her friends as they dawdle down the shore, the speaker expresses, and endures, anxiety about miscarriage. Uncertainty, and sly ambiguity, abound. Who, exactly, is “worried I’d solve this / the easy way”? Only one thing is certain:

one thing constantly

enters another, becoming not one with it

but taking its place, and on and on, a current

On and on indeed. As in Prikryl’s previous collections, repetition is a steering force here. Yet so thoroughly are some phrases tucked and collaged into new lyrical permutations that only faintly do we hear their recurrence. Note the series of 24 interspersed poems — a series apostrophizing trees — that provides the book’s title; “Midwood 1” recalls an archaic fragment:

Out of the garment of the land

out of the

of

There in the ravine the place

that’s deepest,

bent

Scratch that. “Midwood 1” seems less fragmented, more germinal; by “Midwood 12,” we recognize something similar, but much taller, and much sturdier:

Out of the

what if what is

emerging

don’t look

meanwhile the trees are doing their thing

late August thing, sounds like they need some moisturizer

[…]

what if what is emerging is what’s here

The trees in this series are reticent sibyls (“you stand looking gently / down shaking heads / preparing us, your very slow branches saying little”) and volatile diplomatic administrators (“suspends the visas / of the wind and strands the season’s envoy / in another country”); they are corrupt souls (“this is what they are, like me / annoying strivers / in constant danger of making bad choices”) and pure souls (“No one makes of sibilants / a thing as soft as you / do”); they are, at the end of the day, trees (“Out in the open trees behave differently”). Individual entries in this series are enigmatic and therefore praiseworthy. The series’ duration is its problem: it starts to feel effortful.

The book’s strongest poems put on display Prikryl’s self-replenishing gift for striking a match on the side of the most banal and platitudinous of speech:

I sensed you were about to say

Do you know how much I’ve loved you and I said, Oddly yes

but have been baffled as to why

Though increasingly it feels mindless to say that lyric poems demonstrate or exhibit “the logic of dreams,” we often come across this speaker laughing herself awake. A poem like “Custody Hearing” has in spades a dream’s particularity of scene and detail, a dream’s arbitrary dramatis personae:

Mom and I whispering, huddled on a set of bleachers that run all the way around

a conference table, behind the Czech supermodel who’s gained custody

of my son because she is his mother

But that, our speaker knows, isn’t entirely right; she remembers a “delivery room,”

and when the anesthesiologist appeared with his little bucket-like tray forcing

myself to say Actually, his eyebrows going up and my goggled obstetrician telling him

She said no, then the boy squirted out so I thought, well

I cheated and she, his wife, has my baby, it’s natural

Dreams are settings congenial to these unpunctuated poems, many of which feel like dispatches telegraphed from an uneasy, sometimes panicked consciousness. If Prikryl has forfeited the elegant tristesse of The After Party and the ambient grime of No Matter, she has claimed for Midwood a rewarding dailiness. Our speaker wakes up; she goes to sleep; in between, she extracts insight from hardened habitude. “Surprise was my own possession,” she announces. Prikryl’s book joins a consortium of other fine volumes published this year (another is Sandra Lim’s The Curious Thing) that take on the puzzle and astonishment of midlife, of the fact that “the hill we came down is as steep as the hill ahead of us.”

But the less obvious subject of Midwood is the surreality of becoming a parent. Our speaker is the mother of a little boy; groups of children appear readily and everywhere:

And scrambling down the hill

steep as scree, soft loam under dry leaves punctuated by standing figures, trees,

I came to the rear of the school groups and followed them against my inclination

up the mountain, jogging under the chairlift

Amanda who was friendly

and unattractive in an almost fascinating way riding upward to my right

uncomfortable with her weight

There’d been those two slim women in leather jackets

getting wet teaching children how to swim

in a kiddie pool, showing me its faucets

In this poem, “Field Trip” (among the book’s most poignant and resonant), we get to witness Prikryl’s defamiliarizing vision (“soft loam under dry leaves punctuated by standing figures”) and her flair for shrewd assessment (“Amanda who was friendly / and unattractive in an almost fascinating way”). The poem’s account of a dreamlike, mysterious investment in a group of school children on a ski trip (“against my inclination”) manages to communicate as much about the otherworldly experience of bringing another person into existence as any poem that features an explicit description of childbirth:

I felt too inward, unwilling to immerse myself

though down that slope

I’d picked up a small jacket

to carry the rest of the day in case I found its owner

Elsewhere, we glimpse memories and scenes from the speaker’s life before having a child: a life that feels not only like an anterior realm but also like another country, where people speak and write another language: a feeling Prikryl stunningly conjures when she imagines “letters you sent me […] folded in a box a whole day’s drive away.” Another poem remembers an intimate companion tracing “with a finger, slow words on my back or thigh or hand,”

I on yours, a correspondence absent light or sound

especially useful around others, in a car, at the dinner table

This little pas de deux feels like a page torn from the poet’s first book.

As a whole, I can’t help but feel that Midwood has the distractedness of something overgrown, that it would have benefited from more aggressive pruning. Yet individual poems have such an invulnerable coolness and gleaming angularity that I also can’t help but admire how assuredly they distinguish Prikryl from her contemporaries. Midwood’s poems do not invite, shock, take stock, allure, or comfort; they “move through each other” and, slipping out from under our grasp and our presumptions, go their “own way.” They, at every turn, resist us.

Perhaps only for poetry could this assessment be considered a point of profound admiration. I’m beginning to remember that Prikryl herself once wished, in an interview with The Paris Review, for lyric poetry to be more broadly and firmly defined as that “writing which defies mass appreciation, or penetration.” The title of a poem in this book is “Why Not”: it parses out “each shift / in my sled’s / position,”

as I sped down that way and thought

why not

enjoy this, meaning

look at it,

so I looked

It seems to me that “Why Not” is an expression full of encouragement, maybe slight risk; within and about our poetry, it strikes me as something I hope to hear more.

¤

LARB Contributor

Nathan Blansett’s recent poems appear in Ploughshares, New Criterion, American Chordata, and The Southern Review.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Tree of Many: A Review of Three New Poetry Anthologies

Rachel Hadas considers three recently released poetry anthologies.

Healing, Dangerous Wonders: On Sylvia Legris’s “Garden Physic”

Paul J. Pastor reviews Sylvia Legris’s new collection of poetry, “Garden Physic.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!