Healing, Dangerous Wonders: On Sylvia Legris’s “Garden Physic”

Paul J. Pastor reviews Sylvia Legris’s new collection of poetry, “Garden Physic.”

By Paul J. PastorJuly 5, 2022

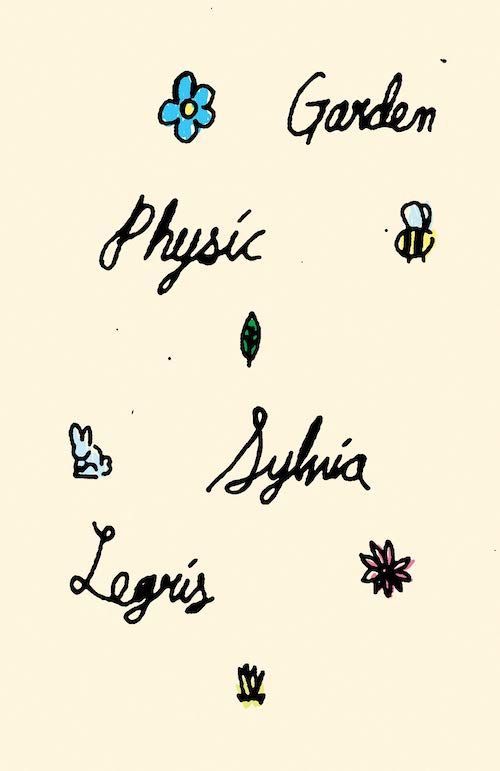

Garden Physic by Sylvia Legris. New Directions. 112 pages.

Give me truths;

For I am weary of the surfaces,

And die of inanition. If I knew

Only the Herbs and simples of the wood,

Rue, cinquefoil, gill, vervain, and agrimony …

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Blight” (1844)

In all Diseases, strengthen the part of the Body afflicted.

— Nicholas Culpeper, Culpeper’s Complete Herbal (1653)

¤

AS YOU READ THIS, perhaps in a folded magazine, perhaps on a computer monitor or the screen of a smartphone, you are likely to be only a few steps away from a plant. Perhaps a succulent, pushed (somewhat neglected) to the corner of a windowsill, perhaps a palm tree or a kitchen garden, perhaps merely a patch of unmown lawn. But the odds are good that, in a few steps, you could touch a member of the kingdom Plantae, one of those little photosynthetic engines with whose sprawling nations our species is so permanently entangled.

The odds are also good that you, like most of us, take these plants utterly for granted — perhaps not even knowing the name for the aforementioned flora in your near vicinity. Most of us in the “developed” world have the dubious privilege of living in a state of natural disconnection from the vegetable life that would be recognizable to nearly all generations of our ancestors. Our dependence is barely less of course, if at all, but our disconnection is profound.

We have become several steps removed from the logic of earth and root that feeds our bodies, provides our modern medicine (roughly 40 percent of drugs in the Western world still are derived directly from plants), or clothes us with fibers. This loss of intimate personal knowledge has, naturally, resulted in a loss of respect for poor, dear kingdom Plantae, a loss that relegates the power and diversity of its members to being, in the minds of many of us, “just plants.”

Of course, there are exceptions. Among such exceptions, folk herbalism is a living tradition. I had the great gift of encountering this tradition as a boy in Oregon, where, in the hills and hollows of the Coast Range and the Willamette Valley, real pockets of this old knowledge persisted. I remember old women in my boyhood church showing me what could be done with the soporific elderflowers and the blue-black berries that would come of them in the late summer. My uncle knew the mysteries of weeds that grew in lawns and backlots, and I grew up, in some small, grateful way, the recipient of an unbroken and living tradition that had been passed to me across many hundreds of years.

But so overwhelming is our general cultural ignorance that the term “plant blindness” was minted by two botanists about 20 years ago to describe the state of glassiness that results when asking contemporary people to truly see the plants around them — a “chronic inability,” according to the Carnegie Museum, “to recognize the importance of plants in the biosphere and in human affairs.” Such blindness is a loss, and for all. It is a loss for people and a loss for the plants, who suffer (with much of the natural world) the burden of human ignorance and disdain through environmental degradation and other species-level insanities. While our interdependence is barely reduced, the daily experience of that interdependence, and the myriad beauties, wonders, and dangers that arise from it, feels very far from the daily life of most of us. Would it not be a good thing, even in a small way, to be healed of such blindness?

It is against this backdrop of the unseen green that Canadian poet Sylvia Legris has offered us her latest collection, Garden Physic. The publisher’s (somewhat bubbly) cover copy promises “a paean to the pleasures and delights of one of the world’s most cherished pastimes: Gardening!” While I understand the exigencies of writing engaging marketing copy, this blurb is not remotely interesting or dangerous enough as a descriptor for the collection, and it runs the risk of turning readers off to the true spirit — and cold fire — of Legris’s latest effort.

To say that Garden Physic is a book about gardening is a sad reduction, something like saying that gardening itself is nothing more than a “cherished pastime.” Perhaps, for some — but to shrink it in such a way carves away the core of it. Sure, it is a pleasant hobby to trim the begonias. But the garden is also a place of revelation, revival, and survival. The garden forms the mythic backdrop of humanity’s great symbolic spiritual crises — Eden and Gethsemane, to name only two of the most archetypal — and, for many faiths, it is the very definition of Paradise.

Rather than “gardening” as such, then, this is a book of poetry about bodies in various states of dependence, power, and collapse, and the garden’s strengthening of those bodies by means of correspondences. In the tradition of old materia medicas, it is an assemblage of things that have worked.

The book praises — obsessively, deliciously — the generous and grotesque glories of the garden for its myriad linkages with the bodies we humans inhabit. In this, Legris is drawing inspiration from pre-modern medical texts (“physics”) that depended for their efficacy on the deft application of centuries of herbal lore and tradition traceable directly to Hippocrates. In this, Garden Physic pairs elegantly with Legris’s 2016 work, The Hideous Hidden, which draws the reader to the absurd and intimate exposures of old anatomical texts. Her interest in such lost bits of knowledge and the ephemera that evoke them is not dead but finds meaning and a living tradition well worthy of her muse.

This is gardening on the level of Hecate or Baba Yaga: sorcerous, numinous, cunningly manipulating the chemical elements of life and death. And in keeping with this magic, Legris’s love for language plays unbounded among the joys of the botanical lexicon. From the scientific names (Ranunculus, Gladiolus, Strelitzia reginae) to the unfathomable treasure of English common names for plants (Savior’s Flannel, Corncockle, Touch-me-not, Throatwort, Quillwort, Bellwort, Pewterwort, Paddock-pipes, Fescue, Pink-O’-The Eye), the richness of sound alone is magic in itself, each name rousing a culture encoded into our all-too-forgotten corners, left behind in a world of paved roads and sterile pharmacies, where a prescription is not given for something you must dig or discover, but where instead all the work and the danger have been done for you, hiding away from your soul and body a path of genuine healing — the doing of the thing, the lore, the knowledge, the connection, the wildness, the danger.

As a poet, Legris is a master of the curving tangent, working her way around a central theme while simply inclining, dropping clippings, allowing the reader to follow, suspended, her careful meanderings, often grounded by a hard-working title or subtle allusion. Her logic, especially in this collection, is not a modern one, and that is a good thing. But neither is she demanding that, by revisiting a largely forgotten herbal tradition, we return to anything remotely sentimental or stodgy, urging us instead to

Forget

the church fathers, the philosophers,

the appropriate and inappropriate authorities.

Forget the know-it-all anthologists,

The squirrelers of curios and collectibles.

(“Plants Further Reduced to the Ideas of Plants”)

Peeled to the quick like an oaken twig (good, I will note from my own interests as a folk herbalist, for tightening loose teeth in their sockets when brewed as a strong tea), Legris’s words know that they, like the efficacy of any cure, will be judged harshly, and by one standard: did this work? Fortunately, the answer is yes. “How to write about flowers without the nauseating sentimental / phraseology?” she asks, in “My Dear Love.” “No quaint, no dainty, no winsome. / This smells good, that / smells bad, my hands rank with manure. This at least is pure.”

Pure it is, with the purity of a slightly unsettling belief. The logic here is the logic of the garden, the old, spilling, rambling garden, full of cuttings and little dry stalks and the wildly diverging futures that any clump of plants can hold. In Legris’s world, as in our own, death waits for us in the hemlock and the monkshood. Life and health rest in the yarrow, the burdock, the meadowsweet, and lady’s mantle.

To fully enter the joys and horrors of this collection, one must think with its governing logic. This is perhaps best done via a principle that rests at the heart of traditional herbalism — the doctrine of signatures. In its most simple form this is the belief, much mocked today, that, say, a plant that looks like a human ear was meant as a curative for maladies of (you will never guess) the ear. In the cold light of science, we can quickly lose interest in such an antiquated — surely dangerous? — notion. But we do so unfairly. After all, does not the humble plantago (lawn plantain) have as its signature five unmistakable strings on the underside of every leaf? And does it not bind a bleeding wound as surely as stitching it together? Chuckle all you want! It does, and there is no better way to remember faithfully its energetic action or to teach it to your children.

And these correspondences, resting in the likenesses between unlike things, animate every page of Garden Physic. If we can suspend that part of the 21st-century mind that has no patience for the inefficiencies or unpredictability of true enchantments, then we can begin to appreciate the rich if imperfect tradition that defined medical life for a majority of our ancestors — and connect, with Legris, the bodies and the plants, the plants and their governing planets, the planets and the whole web of the cosmos. This requires a shift to a different kind of rationality, a mode of thinking where the language of poetry — which ought to be sharp as a diagnosis, attentive as an old doctor — can release the innate ability of our humanity to notice patterns, intuit the meaning and trajectory of those patterns, and harness them for our use.

The falterings in the collection are few, but they are there. One is in the form of the book itself. While the overall effect of the addition of photographs, scanned collages, abrupt changes in type, and so on is clearly in line with Legris’s intention (to create a cottage garden, somewhat messy and spilling over with life), she is a far better poet than she is a photographer or visual artist, and the collection would have been well-served by a firmer editorial grip, reducing visuals solely to attractive typesetting, and a more cohesive presentation of the author’s enigmatic prints of various flowers. This quibble is minor, however, and after the “huh” effect of, say, seeing a small and nearly indecipherable photo that we’re informed is of some bolted rhubarb, we soon return to the powerful physic itself, the genuine mastery of Legris’s lines:

A garden of Cyprian earth fired in kilns.

A garden of white lead scraped and pounded.

Flowers of cadmium from red-hot brass.

Of brass burnt from the nails of ships.

(“Part 2. Flowers of Brass.”)

In its unaccountably beautiful way, Legris’s collection is potent medicine, like a dark tincture or decoction to help treat our simple separation from the natural. Legris forms these too-forgotten names as spells, summoning desire in us to know, to learn, to reconnect. To rise and stand, to find the plant nearest to use, and to know something of it: its texture, perhaps its name. And in this knowing, who knows what we will find? Perhaps poison, perhaps physic. But in either case, with care, we are healed a little of something. The afflicted body, in its way, is strengthened. And so, in Garden Physic we are given a rich gift by a fine contemporary poet, a gift as simple and wonderful as compost, teeming with unpredictable, flourishing life. A gift that may help us pierce our common blindness, salving our eyes a little so that we can better see the truth — that we live, often insensible, in a world of healing, dangerous wonders.

¤

LARB Contributor

Paul J. Pastor is a poet, editor, and author, most recently of Bower Lodge: Poems (Fernwood Press, 2021). He lives in Oregon.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“Writing the Unwritten”: The Poetry of Tom Pickard

Alex Niven reviews Tom Pickard’s “Fiends Fell.”

No More Nature: On Ecopoetics in the Anthropocene

"Poetry might best represent what capitalism has spoiled." Jean-Thomas Tremblay reviews two new books of ecopoetry.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!