IN THE SUMMER OF 2016, ghosts haunted the Arctic.

The details are unsettling. A region in Siberia north of the Arctic Circle called Yamalo-Nenets experienced an unprecedented 18 straight 82 degree Fahrenheit days, and one sweltering 95 degree Fahrenheit day. For Yamalo-Nenets, this constitutes a heat wave of epic proportions. The fallout was immediate and alarming. Permafrost thawed, and then reindeer carcasses and human corpses suspended in the ice thawed as well. And then, far more alarming, the bodies released Anthrax spores, dormant bacteria encased in a tough outer shell. Since the last known Siberian anthrax outbreak occurred in 1941, the bacteria are at least 75 years old.

Here’s the story behind anthrax’s particular resurrection. Reindeer are the primary livelihood for Nenets, once known as Samoyed herders, who inhabit this region. This past summer, over 2,500 reindeer died of anthrax, and 90 people, including more than 50 children, have been hospitalized at this writing. A 12-year-old boy named Denis ate infected reindeer meat, contracted gastrointestinal anthrax, and died on July 30. Russian medical officials now worry that melting permafrost will revive other undead diseases from the 18th and 19th centuries, including smallpox.

Anthrax is not the only ghost haunting the Arctic.

In the Arctic Circle, life seems to keep its own time. If you travel across the Barents Sea from Yamalo-Nenets, you’ll arrive at a Norwegian archipelago called Svalbard. It is an otherworldly place, inhospitable to most life yet starkly and sublimely beautiful. Roughly 2,600 intrepid people, most of them adult men, live here. But you can’t die in Svalbard. No, inhabitants are not immortal. Rather, their life cycles are abridged in mundane ways: Norwegian officials forcibly evict the sick, disabled, and elderly, shipping them back to the Norwegian mainland to end their days. You can’t be born in Svalbard either. The governor orders women in their third trimester to leave. Svalbard is not, as citizens call it, a “life cycle community” — no concessions are made for birth and death, and only able-bodied working adults are welcome. Those verging on dotage are reminded that 20 retirees could bankrupt the town, a message reinforced by the hospital’s scant number of beds and its sole doctor. An elderly person who resists leaving home in the settlement of Longyearbyen is threatened with deportation.

The link between anthrax in Yamalo-Nenets and life in Svalbard is complicated, but key to understanding both is the climate and the ways in which arctic cold transfigures that which is old.

Between 74 and 81 degrees north latitude, north of Norway and east of Greenland, Svalbard is less than 1,000 kilometers from the North Pole. Over 60 percent of its land mass is covered by glaciers. Permafrost renders the ground nearly impenetrable. Three centuries ago, Russian trappers left their dead aboveground throughout the winter, because the earth only softened enough to bury bodies in spring. And arctic temperatures have kept the buried bodies from decomposing — that is, until now. Therein lies the problem. The thawing ground eventually forces bodies buried above permafrost back up until they surface again. So the dead remain fresh, just below the frozen earth, perpetually waiting to be disinterred.

In February 2016, I board a flight from Oslo to Longyearbyen. An anthropologist and historian of biology, I have spent the last 12 years studying changing definitions of “life,” especially in reference to time, most recently focusing my attention on the laboratories of synthetic biologists who design new life forms and attempt to resurrect extinct species. I travel to Svalbard seeking other ways in which life is bound to time — in particular, with regard to temperature. I’ve been promised access to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, colloquially known as the “Doomsday Vault,” a place where seeds are frozen for post-apocalyptic disinterral. But Svalbard, I soon discover, is home to other uncanny triangulations of life, time, and temperature.

On the flight from Oslo, I insulate myself between headphones, listening to Tanya Tagaq, the Inuk throat singer from the Canadian Arctic archipelago. Transported by her ecstatic and ghostly growls, I thumb through A Woman in the Polar Night, a memoir by Christiane Ritter, an Austrian painter who moved to Svalbard in 1934 to join her partner, a German glaciologist. The first European woman to overwinter on the archipelago, Ritter writes bracingly of the polar night: “Outside of time, everything is annihilated. The imprisoned senses circle in the past, in a scene without spatial dimensions, a play in which time stands still.” The plane descends and I see the summit of Platåberget mountain. The sun hasn’t risen since last October. Total darkness blankets the polar circle for four months of the year. Technically, the sun rose a week ago, but at this time of the year, it never climbs above the mountains on the other side of the fjord. During this perpetual twilight, a prolonged late-morning sunrise gives way an hour or two later to an early afternoon sunset that stains the mountaintops pink. It’s not really overcast — the light is limpid and the sky cloudless. But the sunless half-light is eerie and makes every hour seem untimely.

Platåberget, the mountain on which the Longyearbyen airport runway was built, is a desolate place — home, I learn, to an abandoned cemetery, two coal mines, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, and little else. “Gruva” is the Norwegian word for “mine” — from the Old Norse “gröf,” meaning cave, which also gave rise to the English word “grave.” Platåberget is full of vaults and faults, graves and caves. The mountain is now a place to unearth coal and bury coal miners, to immortalize seeds and resurrect viruses. On Platåberget, viruses that lived and died in the past have lately erupted into the present; ruins of coal mines are persistently in the present; and seeds in the vault are artifacts of the present that are now buried for future disinterral. At the ends of the earth, time seems out of joint. Here in the polar north, viruses, coal, and seeds are geopolitical and climatological relics, telling tales of coal extraction, contested land claims, and crumbling empires. And, in the Arctic, geopolitics is decidedly climatological — punctuated by global war, Cold War, and global warming.

Chasing the 1918 Flu Virus

On my first day in Longyearbyen, I look for the town cemetery, which is surprisingly hard to find. With a fjord called Adventfjorden on my right, I first walk to the church, its red spire visible from across the frozen river valley that cuts northwest of town. The church, like most other things in Longyearbyen, boasts being “northernmost”: northernmost commercial airport, northernmost newspaper, northernmost sushi restaurant. I circle the church once, but see no signs of a cemetery. I meet an administrator in the nave, who blinks quizzically when I ask for directions, and then directs me 300 meters along the Platåberget mountainside: don’t cross the bridge, she warns, and don’t pass the white house.

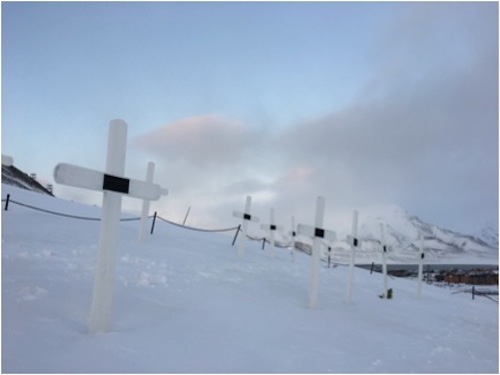

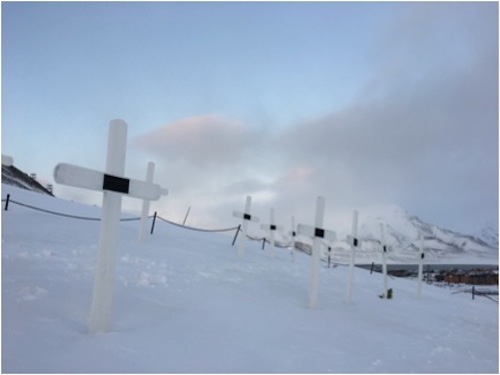

Three times, I mistake fields of wooden stumps for the cemetery. Narrow poles cant acutely from the ground, a kind of German expressionist gesture toward a burial ground. I later learn that these are the piles on which the original homes of Longyear City (now “Longyearbyen”) were built in 1906. German forces shelled and burned them during World War II. But they’re still here. I nearly miss the actual cemetery, though, unable to see it until I am already there: rows of white crosses barely visible against the snow-covered mountainside [Figure 1]. No one has been buried here lately — the highest row of gravestones mark the final resting places of seven miners who died of the “Spanish Lady,” as the 1918 flu was then called.

On September 24, 1918, 69 young men, most of them fishermen or farmers, traveled on board the Forsete from the Norwegian mainland to work in Spitsbergen’s coalmines. In the three days it took them to sail from Tromsø to Longyearbyen, all 69 fell ill. Seven men died within weeks of their arrival; the oldest was just 28. Their deaths are recorded in the diaries kept by Store Norske, the local coal company that had purchased Svalbard mines from the Longyear-owned Arctic Coal Company two years earlier. Store Norske buried them here, on this stark hill overlooking a town they would never see. To save money, their bodies were wrapped like fish in last year’s newspapers.

The bodies of the seven miners remained frozen beneath Platåberget for 80 years until forensic pathologists and archaeologists armed with new DNA-sampling technologies arrived in Longyearbyen to find out whether the flu virus was still biding its time in the Arctic tundra. Researchers had already attempted to exhume victims of the 1918 flu in other parts of the Arctic and in Iceland. As early as 1951, microbiologists had traveled to Brevig Mission (near Nome, Alaska) in an attempt to disinter bodies from a mass grave of Iñupiat flu victims. They were unsuccessful. Fifty years later, after exhuming six of the seven bodies in Longyearbyen cemetery, Canadian medical archaeologists extracted their lung, liver, kidney, and brain tissue using a boring device for taking tree core samples. The genetic material of the 1918 flu, researchers found, was still there — bits of ribonucleic acid (RNA) fragmented in the bodies. Back in the laboratory, researchers cultured the bacteria clinging to lung tissue; still alive, they grew hardily when placed in nutrient broth and heated to body temperature.

Seven years after the bodies were exhumed in Svalbard, the genetic sequence of the “extinct” virus was revived, not from the Svalbard samples, but from a different piece of human tissue kept frozen in a pathology archive in Washington, DC. The sequence was confirmed using another body that had been preserved in the mass grave in Brevig Mission, Alaska. That year, the entirety of the sequence of the 1918 flu was published in Nature and online, and researchers at the CDC in Atlanta sprayed the virus into the noses of mice, all of which died within days. The Spanish Lady’s resurrection ignited a furor among biologists and ethicists who were horrified by how easy it was to revive this latent flu. They worried that a bioterrorist could easily download the sequence from a public database, order the virus from a DNA synthesis company, and then have it shipped back via FedEx.

Does this mean that that we are now “haunted,” as newspapers and science journals would have it, by the “specter” of a virus that lived, died, and was brought to life again?

Coal [1]

Longyearbyen is named for John Munro Longyear, an American capitalist whose name itself suggests a kind of temporal slackening. Longyear arrived in Svalbard and espied riches in the plentiful Triassic coal seams that marked the land, exposed by glacial gashes. Coal is, of course, dead organic matter. All of that shiny black sediment is the detritus of deciduous forests and puzzlegrass that flourished in a balmier Svalbard 65 to 23 million years ago, their dead tissue inspissated by heat and pressure until latent energy condensed into something combustible.

Longyear’s Arctic Coal Company began operating in 1906; its first mine was dug into Platåberget’s slopes directly above the graveyard, though the graveyard wasn’t there yet. Coal-mining culture persists among citizens of Longyearbyen, recognizable in the small daily rituals of the townspeople. Taking off your snow boots in the mudroom before entering homes and businesses is a throwback to the days when miners avoided tramping coal dust indoors. Many citizens carry slippers to wear indoors, and schools, museums, and hotels provide communal shoes that guests can borrow.

One night I have dinner with a Norwegian paleontologist who is in town to lecture at UNIS, the local university. He tells me he first visited Longyearbyen as a teenager to work the mines. He points across the street to the building that now houses a coffee shop, a few outdoor clothing stores, and the local library. That used to be the company sauna, he explains. At the end of each day, miners would strip off their filthy clothes and steam themselves clean before putting on their evening clothes. Every morning, they went through the same ritual in reverse.

Even though coal mining in Longyearbyen is largely shuttered, its infrastructure remains scattered across Longyearbyen’s landscape [Figure 2]. The dark skeletal remains of coal tipples, lift systems, and aerial tramway conveyors litter the surrounding mountains, looking much the way Store Norske left them in 1958 — they resist decay because the temperature is too cold for liquid water to rot wood. They are ruins, and will most likely remain so indefinitely.

Across the fjord from Longyearbyen is a ghost mining town called Pyramiden. Abandoned to the elements in 1998, Soviets had designed Pyramiden to conquer the formidable climate of the high arctic: miners could swim in a salt-water swimming pool, eat from a greenhouse that grew cucumbers and herbs, and walk across green grass specially cultivated to be hardy enough to flourish in the frigid town square. The city also boasted a basketball court, a library, a nightclub, and a museum, among other urban conveniences.

Ten years after its closure, two archaeologists and a photographer documented the ghost town’s posthumous existence. They found there a weathered and blasted “antonym of the modern.” [2] After my bone-chilling pilgrimage to the Longyearbyen cemetery, I walk back into town and sit at one of the two local bars, eating reindeer steak and sipping aquavit beneath Lenin’s steely gaze. I ask the bartender what she knows about this bust. She shrugs, “someone found it over in Pyramiden a few years ago” [Figure 3].

Longyearbyen is now also an abandoned coal-mining town. Scientists are taking the miners’ place, propping up a flagging economy with research grants from nations around the world. The mines in the nearby settlement of Ny-Ålesund closed after an explosion killed 21 miners in 1962, but today the town enjoys new life as a research station. Each mining cabin now belongs to a different nationality of scientists, the Chinese station being the oldest. Ironically, these scientists are in Svalbard to observe anthropogenic climate change. As all that coal combusted, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels rose, and the glaciers whose tongues and feet and snouts had waxed and waned along depressed arêtes for hundreds of thousands of years began receding. As their mass balances shifted, they calved and let loose and the temperatures rose, and the waters rose, unleashing a terrible positive feedback cycle.

Seed

What will become of life, then, as the climate warms and these glaciers recede — as ecological catastrophe joins geopolitical catastrophe to make this and every other place precarious and unlivable? In 1984, agricultural researchers from a Norwegian university decided to conduct what they termed a “hundred-year experiment.” They gathered a small collection of seeds and stored them underground in Mine 3 on a Platåberget pass just past the Longyearbyen airport. The interior of the coal mine maintains an ambient temperature between -2.5 and -3.5 degrees Celsius, far enough below freezing that, the researchers suspected, seeds would be naturally preserved. Checking one year to the next, the researchers confirmed the seeds’ suspended animation: none have germinated. The Norwegian scientists made a proposal to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO): since there was plenty more room in this mine shaft, now repurposed as a naturally occurring cryobank, other countries might want to pay a small fee in order to archive their own seeds. The UN turned them down, on the grounds that intellectual property disputes might arise if one country stored a significant amount of its national germplasm in another nation’s territory. The mine shuttered in 1996 when its thin coal seam was exhausted. The seeds stored in 1984 are still there.

That is where a man named Cary Fowler enters the story. Raised in Memphis, Tennessee, Fowler has devoted his career to social justice and agricultural security. He fondly recalls days spent at his grandmother’s farm and tells me what it was like to be in the room when Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech. In the 1990s, he served the FAO and helped negotiate the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources. In 2003, the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) received 13.6 million USD from the World Bank to update its 11 gene banks, which collectively held over 600,000 agricultural genetic resources. As director of the Global Crop Diversity Trust, Fowler assisted in the project, which was overseen by his friend and colleague Henry Shands. At the time, Shands was also director of the National Seed Storage Lab in Fort Collins, Colorado.

Fowler and Shands celebrated the project’s end in 2005, after all the CGIAR gene banks had been updated. But in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, Fowler began to wonder whether agricultural diversity could ever truly be secure if cities were so vulnerable to geopolitical and ecological disaster. He and Shands realized that the gene banks were located in places where the best technological infrastructure could be quickly dismantled by political strife or natural disaster — Nigeria, Colombia, Nairobi, Kenya, Nepal. It was then that Fowler recalled the Norwegian scientists whose failed proposal had crossed his desk years earlier at the FAO. Back then, he had nixed the proposal, but now he thought differently: a vault dug into the permafrost beneath Platåberget seemed as safe a place as any, and perhaps safer than most.

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault broke ground soon thereafter.

The day after I went looking for the graves of Spanish flu victims, Fowler called to invite me to join him at the Seed Vault. He picks me up the following morning and we drive out of town, past the airport and up a mountain pass leading to Gruve 3. As Fowler and I ascend Platåberget, a small herd of reindeer forages dispiritedly on a few hardy lichens; Fowler points out an arctic fox peering down at us from a roadside crevasse. As he parks on a flat patch of icy earth on a cliff overlooking the water, Fowler tells me that he had hoped to build the vault somewhere more remote, a comment that strikes me as laughable, given our godforsaken surroundings. Gesturing downhill, he points out the air traffic control tower for the Longyearbyen airport, and explains that this location allows the air traffic controllers to keep an eye on the vault and sound an alarm if they notice an intruder.

A thin cement wedge piercing the frozen mountainside at a steep incline, the vault’s Brutalist exterior suggests how deeply it is lodged beneath the earth [Figure 4]. Above the doors and along the roof is an installation of prisms and fiber-optic cables that reflect the midnight sun in the summer and glitter like the aurora borealis during the polar night. It looks like a post-apocalyptic bunker, which, I suppose, is exactly what it is. Conspiracy theories about the vault swirl among citizens of Svalbard. Some claim it is actually owned by Monsanto; others whisper that it is a secret base for NATO. Earlier in the millennium, they said that it was built in preparation for the end of the world in 2012, as foretold by misreadings of the Mayan calendar. One rumor has it that the vault is part of a eugenics experiment in which one-half of Norwegians will be sustained underground as the rest of the global population is decimated, so that they may later emerge to repopulate the planet with their Nordic genomes.

At first, the Doomsday Vault seems to keep evangelical time. Millennial anticipation oscillates between apocalypse and salvation, with nothing in between. Millenarians either welcome doomsday with open arms or they stockpile beef jerky and Bitcoin, and sometimes they do both. The point is that the end: it’s nigh. The present is reduced to a horizon in which to anticipate the end of days. This is the pervasive attitude of our times — just turn on the news.

The doors slam heavily behind us, and we face a long hallway, really a tube of corrugated metal sloping downward into the mountain. Everything is duplicated: ventilation, backup generators, and pumps. There’s no use for one water-pump, let alone two, in a hole beneath permafrost, but the building’s designers have prepared for a future when the permafrost has thawed. Engineers have planned ahead in other ways as well. For instance, they surveyed the mountain to ensure that the vault is nowhere near a coal seam. Their reasoning was that a century or more from now, when the vault is forgotten, miners may return to this mountain seeking coal seams, only to inadvertently drill into the vault. The engineers also accounted for a 70-meter sea level rise, which is an estimate of what would happen if all the glaciers in the world melted. They compounded that scenario with a tsunami, and then built the vault five stories above the predicted waterline. Engineers calculate that, given the current rate of climate change, the vault would remain below freezing even if the electricity went out for the next two centuries. How long did you build it to last, I ask? Fowler: “Essentially forever.”

Fowler unlocks another pair of heavy doors: “This next room’s my favorite.” My twinkly-eyed trickster-guide is the Willy Wonka of the Eschaton, and the room into which he escorts me next is wondrous indeed: a stark and cavernous antechamber of raw limestone hollowed into vaulted ceilings and washed in white reinforced concrete, rock rimed in frost. “I really enjoy being here,” Fowler murmurs, and his voice reverberates. The wall opposite the doors through which we entered is gently concave; to our left, two doors are offset, and a third door is on the other side of the parabolic bare wall. Fowler explains that they avoided putting any of the interior chambers directly opposite the door leading to the hallway so that “if someone were to fire a missile down here … it wouldn’t hit the place where the seeds are.” So, too, the wall is concave so that shockwaves — from a ballistic missile or a plane crashing into the mountain, for example — can reflect back toward the entrance instead of propagating deeper into the mountain and injuring the seeds.

As I photograph the interior of the vault, I ruminate on my anthropological training. Salvage anthropologists and salvage biologists have been allied for over a century in their efforts to capture and preserve endangered cultures, species, plants, seeds, blood, languages, and ecosystems. In this sense, I have the uneasy feeling that, at least from a disciplinary perspective, Fowler and I have much in common. Bronisław Malinowski inaugurated modern anthropology when he was stranded on the Trobriand Islands during World War I. In the first sentences of Argonauts of the Western Pacific, he identifies anthropology’s origin in the tragedy of history: “Ethnology is in the sadly ludicrous, not to say tragic, position, that at the very moment when it begins to put its workshop in order, to forge its proper tools, to start ready for work on its appointed task, the material of its study melts away with hopeless rapidity.” A hundred years later, biologists bank on similar notions of endangerment to frame their scientific enterprise and to jumpstart a sensibility in which freezing can arrest the endangered past — in this case, a global agricultural heritage at risk of “melt[ing] away.”

The door to vault #2 is overgrown with frost, which has crystallized around the doorframe and bloomed across the door handle. Minus 18 degrees Celsius is a sucker punch. Yet here is abundant life: 860,000 different varieties of crops, and 120,000 different strains of rice alone. Seeds are sealed in triple-ply, puncture-resistant vacuum packaging and then loaded into plastic crates, which are stacked on shelves. Looking inside one box, I find ampules of squash and bags of anise. Every major crop in the world is in this room — not just wheat, oats, barley, potatoes, lentils, soybeans, and alfalfa, but also heirloom seeds and forgotten landraces. Boxfuls of foraged grasses are stored cheek-by-jowl alongside sorghum, foxtail millet, bur clover, purple bush-beans, pigeon peas, Kentucky bluegrass, and creeping beggarweed. Every country in the world is represented, as are several countries that no longer exist. Colombia, North Korea, Russia, Taiwan, Ukraine, Switzerland, Nigeria, Germany, Israel, Syria, Zimbabwe, Tajikistan, and Armenia share shelf-space in this pastoral League of Nations. With over 90 million seeds deposited in the bank, India represents the largest crop diversity, nearly three times as much as Mexico, the next most prolific contributor.

On February 26, 2008, the day the seed vault opened, Pakistan and Kenya were first in line to store their seeds. The previous year, the disputed election of Mwai Kibaki in Kenya triggered ethnic violence against Kikuyus. Karachi had catastrophically flooded and was scene to a bloody suicide bombing, and Benazir Bhutto was assassinated in Rawalpindi. One can speculate that, for Kenya and Pakistan, a cache in the Seed Vault is a way to refuse political and climatological vulnerability — to forecast a future that might, somehow, sustain life.

One shelf of the vault is half empty. Four years into the civil war and humanitarian crisis in Syria, violence barreling northward toward Aleppo jeopardized the Headquarters of the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA). Hundreds of thousands of seeds were banked here in Svalbard, including some of the earliest strains of Levantine wheat and durum, which are more than 10 thousand years old. The Syrian gene bank, now relocated to Morocco and Lebanon, recently requested 30 thousand samples from its original collection to help rebuild the country’s stores of barley, lentils, and chickpeas.

After an hour in the vault, my hands have become dumb appendages in a worryingly cadaveric shade. The cold has muscled through the seams of my coat, and my camera died within minutes of entering vault #2. Fowler and I retrace our steps and head back outdoors.

Standing at the edge of Platåberget mountain cast in perpetual twilight, Fowler marvels at the irony: “We’ve got the largest collection of agricultural biodiversity in the world here, where there aren’t any farms or gardens or trees or even an outdoor plant.” I nod in response, because here, on the surface of things, it seems as if nothing is alive. Yet Platåberget teems with subcutaneous life, paused and sedimented into the mountain’s warped and overlapping temporalities in a state of deferred potential. Here, some life is slower than molasses on a snow day, and some is stuck firmly in the past. But much of the latter is uncannily durable, perpetually present in the present. It lags; it persists. It promises to last forever, even as it is endangered. It can be patient as a saint, and quiet to the point of cryptic. Yet these temporal distortions, like those in Yamalo-Nenets, are climatological: time is tuned to temperature. And the temperatures are rising.

[1] Excerpts from this section were previously published online as “Ruin" in Theorizing the Contemporary, Cultural Anthropology website, September 30, 2016 (available here: https://culanth.org/fieldsights/959-ruin). Reproduced courtesy of Cultural Anthropology.

[2] Elin Andreassen, Hein B. Bjerck, and Bjørnar Olsen, Persistent Memories: Pyramiden -- A Soviet Mining Town in the High Arctic (Trondheim, Norway: Fagbokforlaget, 2010), 142.

The details are unsettling. A region in Siberia north of the Arctic Circle called Yamalo-Nenets experienced an unprecedented 18 straight 82 degree Fahrenheit days, and one sweltering 95 degree Fahrenheit day. For Yamalo-Nenets, this constitutes a heat wave of epic proportions. The fallout was immediate and alarming. Permafrost thawed, and then reindeer carcasses and human corpses suspended in the ice thawed as well. And then, far more alarming, the bodies released Anthrax spores, dormant bacteria encased in a tough outer shell. Since the last known Siberian anthrax outbreak occurred in 1941, the bacteria are at least 75 years old.

Here’s the story behind anthrax’s particular resurrection. Reindeer are the primary livelihood for Nenets, once known as Samoyed herders, who inhabit this region. This past summer, over 2,500 reindeer died of anthrax, and 90 people, including more than 50 children, have been hospitalized at this writing. A 12-year-old boy named Denis ate infected reindeer meat, contracted gastrointestinal anthrax, and died on July 30. Russian medical officials now worry that melting permafrost will revive other undead diseases from the 18th and 19th centuries, including smallpox.

Anthrax is not the only ghost haunting the Arctic.

In the Arctic Circle, life seems to keep its own time. If you travel across the Barents Sea from Yamalo-Nenets, you’ll arrive at a Norwegian archipelago called Svalbard. It is an otherworldly place, inhospitable to most life yet starkly and sublimely beautiful. Roughly 2,600 intrepid people, most of them adult men, live here. But you can’t die in Svalbard. No, inhabitants are not immortal. Rather, their life cycles are abridged in mundane ways: Norwegian officials forcibly evict the sick, disabled, and elderly, shipping them back to the Norwegian mainland to end their days. You can’t be born in Svalbard either. The governor orders women in their third trimester to leave. Svalbard is not, as citizens call it, a “life cycle community” — no concessions are made for birth and death, and only able-bodied working adults are welcome. Those verging on dotage are reminded that 20 retirees could bankrupt the town, a message reinforced by the hospital’s scant number of beds and its sole doctor. An elderly person who resists leaving home in the settlement of Longyearbyen is threatened with deportation.

The link between anthrax in Yamalo-Nenets and life in Svalbard is complicated, but key to understanding both is the climate and the ways in which arctic cold transfigures that which is old.

Between 74 and 81 degrees north latitude, north of Norway and east of Greenland, Svalbard is less than 1,000 kilometers from the North Pole. Over 60 percent of its land mass is covered by glaciers. Permafrost renders the ground nearly impenetrable. Three centuries ago, Russian trappers left their dead aboveground throughout the winter, because the earth only softened enough to bury bodies in spring. And arctic temperatures have kept the buried bodies from decomposing — that is, until now. Therein lies the problem. The thawing ground eventually forces bodies buried above permafrost back up until they surface again. So the dead remain fresh, just below the frozen earth, perpetually waiting to be disinterred.

¤

In February 2016, I board a flight from Oslo to Longyearbyen. An anthropologist and historian of biology, I have spent the last 12 years studying changing definitions of “life,” especially in reference to time, most recently focusing my attention on the laboratories of synthetic biologists who design new life forms and attempt to resurrect extinct species. I travel to Svalbard seeking other ways in which life is bound to time — in particular, with regard to temperature. I’ve been promised access to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, colloquially known as the “Doomsday Vault,” a place where seeds are frozen for post-apocalyptic disinterral. But Svalbard, I soon discover, is home to other uncanny triangulations of life, time, and temperature.

On the flight from Oslo, I insulate myself between headphones, listening to Tanya Tagaq, the Inuk throat singer from the Canadian Arctic archipelago. Transported by her ecstatic and ghostly growls, I thumb through A Woman in the Polar Night, a memoir by Christiane Ritter, an Austrian painter who moved to Svalbard in 1934 to join her partner, a German glaciologist. The first European woman to overwinter on the archipelago, Ritter writes bracingly of the polar night: “Outside of time, everything is annihilated. The imprisoned senses circle in the past, in a scene without spatial dimensions, a play in which time stands still.” The plane descends and I see the summit of Platåberget mountain. The sun hasn’t risen since last October. Total darkness blankets the polar circle for four months of the year. Technically, the sun rose a week ago, but at this time of the year, it never climbs above the mountains on the other side of the fjord. During this perpetual twilight, a prolonged late-morning sunrise gives way an hour or two later to an early afternoon sunset that stains the mountaintops pink. It’s not really overcast — the light is limpid and the sky cloudless. But the sunless half-light is eerie and makes every hour seem untimely.

Platåberget, the mountain on which the Longyearbyen airport runway was built, is a desolate place — home, I learn, to an abandoned cemetery, two coal mines, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, and little else. “Gruva” is the Norwegian word for “mine” — from the Old Norse “gröf,” meaning cave, which also gave rise to the English word “grave.” Platåberget is full of vaults and faults, graves and caves. The mountain is now a place to unearth coal and bury coal miners, to immortalize seeds and resurrect viruses. On Platåberget, viruses that lived and died in the past have lately erupted into the present; ruins of coal mines are persistently in the present; and seeds in the vault are artifacts of the present that are now buried for future disinterral. At the ends of the earth, time seems out of joint. Here in the polar north, viruses, coal, and seeds are geopolitical and climatological relics, telling tales of coal extraction, contested land claims, and crumbling empires. And, in the Arctic, geopolitics is decidedly climatological — punctuated by global war, Cold War, and global warming.

Chasing the 1918 Flu Virus

On my first day in Longyearbyen, I look for the town cemetery, which is surprisingly hard to find. With a fjord called Adventfjorden on my right, I first walk to the church, its red spire visible from across the frozen river valley that cuts northwest of town. The church, like most other things in Longyearbyen, boasts being “northernmost”: northernmost commercial airport, northernmost newspaper, northernmost sushi restaurant. I circle the church once, but see no signs of a cemetery. I meet an administrator in the nave, who blinks quizzically when I ask for directions, and then directs me 300 meters along the Platåberget mountainside: don’t cross the bridge, she warns, and don’t pass the white house.

Figure 1. The Longyearbyen Cemetery. Photo by author.

Three times, I mistake fields of wooden stumps for the cemetery. Narrow poles cant acutely from the ground, a kind of German expressionist gesture toward a burial ground. I later learn that these are the piles on which the original homes of Longyear City (now “Longyearbyen”) were built in 1906. German forces shelled and burned them during World War II. But they’re still here. I nearly miss the actual cemetery, though, unable to see it until I am already there: rows of white crosses barely visible against the snow-covered mountainside [Figure 1]. No one has been buried here lately — the highest row of gravestones mark the final resting places of seven miners who died of the “Spanish Lady,” as the 1918 flu was then called.

On September 24, 1918, 69 young men, most of them fishermen or farmers, traveled on board the Forsete from the Norwegian mainland to work in Spitsbergen’s coalmines. In the three days it took them to sail from Tromsø to Longyearbyen, all 69 fell ill. Seven men died within weeks of their arrival; the oldest was just 28. Their deaths are recorded in the diaries kept by Store Norske, the local coal company that had purchased Svalbard mines from the Longyear-owned Arctic Coal Company two years earlier. Store Norske buried them here, on this stark hill overlooking a town they would never see. To save money, their bodies were wrapped like fish in last year’s newspapers.

The bodies of the seven miners remained frozen beneath Platåberget for 80 years until forensic pathologists and archaeologists armed with new DNA-sampling technologies arrived in Longyearbyen to find out whether the flu virus was still biding its time in the Arctic tundra. Researchers had already attempted to exhume victims of the 1918 flu in other parts of the Arctic and in Iceland. As early as 1951, microbiologists had traveled to Brevig Mission (near Nome, Alaska) in an attempt to disinter bodies from a mass grave of Iñupiat flu victims. They were unsuccessful. Fifty years later, after exhuming six of the seven bodies in Longyearbyen cemetery, Canadian medical archaeologists extracted their lung, liver, kidney, and brain tissue using a boring device for taking tree core samples. The genetic material of the 1918 flu, researchers found, was still there — bits of ribonucleic acid (RNA) fragmented in the bodies. Back in the laboratory, researchers cultured the bacteria clinging to lung tissue; still alive, they grew hardily when placed in nutrient broth and heated to body temperature.

Seven years after the bodies were exhumed in Svalbard, the genetic sequence of the “extinct” virus was revived, not from the Svalbard samples, but from a different piece of human tissue kept frozen in a pathology archive in Washington, DC. The sequence was confirmed using another body that had been preserved in the mass grave in Brevig Mission, Alaska. That year, the entirety of the sequence of the 1918 flu was published in Nature and online, and researchers at the CDC in Atlanta sprayed the virus into the noses of mice, all of which died within days. The Spanish Lady’s resurrection ignited a furor among biologists and ethicists who were horrified by how easy it was to revive this latent flu. They worried that a bioterrorist could easily download the sequence from a public database, order the virus from a DNA synthesis company, and then have it shipped back via FedEx.

Does this mean that that we are now “haunted,” as newspapers and science journals would have it, by the “specter” of a virus that lived, died, and was brought to life again?

Coal [1]

Longyearbyen is named for John Munro Longyear, an American capitalist whose name itself suggests a kind of temporal slackening. Longyear arrived in Svalbard and espied riches in the plentiful Triassic coal seams that marked the land, exposed by glacial gashes. Coal is, of course, dead organic matter. All of that shiny black sediment is the detritus of deciduous forests and puzzlegrass that flourished in a balmier Svalbard 65 to 23 million years ago, their dead tissue inspissated by heat and pressure until latent energy condensed into something combustible.

Longyear’s Arctic Coal Company began operating in 1906; its first mine was dug into Platåberget’s slopes directly above the graveyard, though the graveyard wasn’t there yet. Coal-mining culture persists among citizens of Longyearbyen, recognizable in the small daily rituals of the townspeople. Taking off your snow boots in the mudroom before entering homes and businesses is a throwback to the days when miners avoided tramping coal dust indoors. Many citizens carry slippers to wear indoors, and schools, museums, and hotels provide communal shoes that guests can borrow.

One night I have dinner with a Norwegian paleontologist who is in town to lecture at UNIS, the local university. He tells me he first visited Longyearbyen as a teenager to work the mines. He points across the street to the building that now houses a coffee shop, a few outdoor clothing stores, and the local library. That used to be the company sauna, he explains. At the end of each day, miners would strip off their filthy clothes and steam themselves clean before putting on their evening clothes. Every morning, they went through the same ritual in reverse.

Figure 2. Remains of Gruve 1, Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani, Longyearbyen. Photo by author.

Even though coal mining in Longyearbyen is largely shuttered, its infrastructure remains scattered across Longyearbyen’s landscape [Figure 2]. The dark skeletal remains of coal tipples, lift systems, and aerial tramway conveyors litter the surrounding mountains, looking much the way Store Norske left them in 1958 — they resist decay because the temperature is too cold for liquid water to rot wood. They are ruins, and will most likely remain so indefinitely.

Across the fjord from Longyearbyen is a ghost mining town called Pyramiden. Abandoned to the elements in 1998, Soviets had designed Pyramiden to conquer the formidable climate of the high arctic: miners could swim in a salt-water swimming pool, eat from a greenhouse that grew cucumbers and herbs, and walk across green grass specially cultivated to be hardy enough to flourish in the frigid town square. The city also boasted a basketball court, a library, a nightclub, and a museum, among other urban conveniences.

Ten years after its closure, two archaeologists and a photographer documented the ghost town’s posthumous existence. They found there a weathered and blasted “antonym of the modern.” [2] After my bone-chilling pilgrimage to the Longyearbyen cemetery, I walk back into town and sit at one of the two local bars, eating reindeer steak and sipping aquavit beneath Lenin’s steely gaze. I ask the bartender what she knows about this bust. She shrugs, “someone found it over in Pyramiden a few years ago” [Figure 3].

Figure 3. Bust of Lenin, Longyearbyen. Photo by author.

Longyearbyen is now also an abandoned coal-mining town. Scientists are taking the miners’ place, propping up a flagging economy with research grants from nations around the world. The mines in the nearby settlement of Ny-Ålesund closed after an explosion killed 21 miners in 1962, but today the town enjoys new life as a research station. Each mining cabin now belongs to a different nationality of scientists, the Chinese station being the oldest. Ironically, these scientists are in Svalbard to observe anthropogenic climate change. As all that coal combusted, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels rose, and the glaciers whose tongues and feet and snouts had waxed and waned along depressed arêtes for hundreds of thousands of years began receding. As their mass balances shifted, they calved and let loose and the temperatures rose, and the waters rose, unleashing a terrible positive feedback cycle.

Seed

What will become of life, then, as the climate warms and these glaciers recede — as ecological catastrophe joins geopolitical catastrophe to make this and every other place precarious and unlivable? In 1984, agricultural researchers from a Norwegian university decided to conduct what they termed a “hundred-year experiment.” They gathered a small collection of seeds and stored them underground in Mine 3 on a Platåberget pass just past the Longyearbyen airport. The interior of the coal mine maintains an ambient temperature between -2.5 and -3.5 degrees Celsius, far enough below freezing that, the researchers suspected, seeds would be naturally preserved. Checking one year to the next, the researchers confirmed the seeds’ suspended animation: none have germinated. The Norwegian scientists made a proposal to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO): since there was plenty more room in this mine shaft, now repurposed as a naturally occurring cryobank, other countries might want to pay a small fee in order to archive their own seeds. The UN turned them down, on the grounds that intellectual property disputes might arise if one country stored a significant amount of its national germplasm in another nation’s territory. The mine shuttered in 1996 when its thin coal seam was exhausted. The seeds stored in 1984 are still there.

That is where a man named Cary Fowler enters the story. Raised in Memphis, Tennessee, Fowler has devoted his career to social justice and agricultural security. He fondly recalls days spent at his grandmother’s farm and tells me what it was like to be in the room when Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech. In the 1990s, he served the FAO and helped negotiate the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources. In 2003, the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) received 13.6 million USD from the World Bank to update its 11 gene banks, which collectively held over 600,000 agricultural genetic resources. As director of the Global Crop Diversity Trust, Fowler assisted in the project, which was overseen by his friend and colleague Henry Shands. At the time, Shands was also director of the National Seed Storage Lab in Fort Collins, Colorado.

Fowler and Shands celebrated the project’s end in 2005, after all the CGIAR gene banks had been updated. But in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, Fowler began to wonder whether agricultural diversity could ever truly be secure if cities were so vulnerable to geopolitical and ecological disaster. He and Shands realized that the gene banks were located in places where the best technological infrastructure could be quickly dismantled by political strife or natural disaster — Nigeria, Colombia, Nairobi, Kenya, Nepal. It was then that Fowler recalled the Norwegian scientists whose failed proposal had crossed his desk years earlier at the FAO. Back then, he had nixed the proposal, but now he thought differently: a vault dug into the permafrost beneath Platåberget seemed as safe a place as any, and perhaps safer than most.

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault broke ground soon thereafter.

¤

The day after I went looking for the graves of Spanish flu victims, Fowler called to invite me to join him at the Seed Vault. He picks me up the following morning and we drive out of town, past the airport and up a mountain pass leading to Gruve 3. As Fowler and I ascend Platåberget, a small herd of reindeer forages dispiritedly on a few hardy lichens; Fowler points out an arctic fox peering down at us from a roadside crevasse. As he parks on a flat patch of icy earth on a cliff overlooking the water, Fowler tells me that he had hoped to build the vault somewhere more remote, a comment that strikes me as laughable, given our godforsaken surroundings. Gesturing downhill, he points out the air traffic control tower for the Longyearbyen airport, and explains that this location allows the air traffic controllers to keep an eye on the vault and sound an alarm if they notice an intruder.

A thin cement wedge piercing the frozen mountainside at a steep incline, the vault’s Brutalist exterior suggests how deeply it is lodged beneath the earth [Figure 4]. Above the doors and along the roof is an installation of prisms and fiber-optic cables that reflect the midnight sun in the summer and glitter like the aurora borealis during the polar night. It looks like a post-apocalyptic bunker, which, I suppose, is exactly what it is. Conspiracy theories about the vault swirl among citizens of Svalbard. Some claim it is actually owned by Monsanto; others whisper that it is a secret base for NATO. Earlier in the millennium, they said that it was built in preparation for the end of the world in 2012, as foretold by misreadings of the Mayan calendar. One rumor has it that the vault is part of a eugenics experiment in which one-half of Norwegians will be sustained underground as the rest of the global population is decimated, so that they may later emerge to repopulate the planet with their Nordic genomes.

Figure 4. Exterior of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Photo by author.

At first, the Doomsday Vault seems to keep evangelical time. Millennial anticipation oscillates between apocalypse and salvation, with nothing in between. Millenarians either welcome doomsday with open arms or they stockpile beef jerky and Bitcoin, and sometimes they do both. The point is that the end: it’s nigh. The present is reduced to a horizon in which to anticipate the end of days. This is the pervasive attitude of our times — just turn on the news.

The doors slam heavily behind us, and we face a long hallway, really a tube of corrugated metal sloping downward into the mountain. Everything is duplicated: ventilation, backup generators, and pumps. There’s no use for one water-pump, let alone two, in a hole beneath permafrost, but the building’s designers have prepared for a future when the permafrost has thawed. Engineers have planned ahead in other ways as well. For instance, they surveyed the mountain to ensure that the vault is nowhere near a coal seam. Their reasoning was that a century or more from now, when the vault is forgotten, miners may return to this mountain seeking coal seams, only to inadvertently drill into the vault. The engineers also accounted for a 70-meter sea level rise, which is an estimate of what would happen if all the glaciers in the world melted. They compounded that scenario with a tsunami, and then built the vault five stories above the predicted waterline. Engineers calculate that, given the current rate of climate change, the vault would remain below freezing even if the electricity went out for the next two centuries. How long did you build it to last, I ask? Fowler: “Essentially forever.”

Fowler unlocks another pair of heavy doors: “This next room’s my favorite.” My twinkly-eyed trickster-guide is the Willy Wonka of the Eschaton, and the room into which he escorts me next is wondrous indeed: a stark and cavernous antechamber of raw limestone hollowed into vaulted ceilings and washed in white reinforced concrete, rock rimed in frost. “I really enjoy being here,” Fowler murmurs, and his voice reverberates. The wall opposite the doors through which we entered is gently concave; to our left, two doors are offset, and a third door is on the other side of the parabolic bare wall. Fowler explains that they avoided putting any of the interior chambers directly opposite the door leading to the hallway so that “if someone were to fire a missile down here … it wouldn’t hit the place where the seeds are.” So, too, the wall is concave so that shockwaves — from a ballistic missile or a plane crashing into the mountain, for example — can reflect back toward the entrance instead of propagating deeper into the mountain and injuring the seeds.

As I photograph the interior of the vault, I ruminate on my anthropological training. Salvage anthropologists and salvage biologists have been allied for over a century in their efforts to capture and preserve endangered cultures, species, plants, seeds, blood, languages, and ecosystems. In this sense, I have the uneasy feeling that, at least from a disciplinary perspective, Fowler and I have much in common. Bronisław Malinowski inaugurated modern anthropology when he was stranded on the Trobriand Islands during World War I. In the first sentences of Argonauts of the Western Pacific, he identifies anthropology’s origin in the tragedy of history: “Ethnology is in the sadly ludicrous, not to say tragic, position, that at the very moment when it begins to put its workshop in order, to forge its proper tools, to start ready for work on its appointed task, the material of its study melts away with hopeless rapidity.” A hundred years later, biologists bank on similar notions of endangerment to frame their scientific enterprise and to jumpstart a sensibility in which freezing can arrest the endangered past — in this case, a global agricultural heritage at risk of “melt[ing] away.”

The door to vault #2 is overgrown with frost, which has crystallized around the doorframe and bloomed across the door handle. Minus 18 degrees Celsius is a sucker punch. Yet here is abundant life: 860,000 different varieties of crops, and 120,000 different strains of rice alone. Seeds are sealed in triple-ply, puncture-resistant vacuum packaging and then loaded into plastic crates, which are stacked on shelves. Looking inside one box, I find ampules of squash and bags of anise. Every major crop in the world is in this room — not just wheat, oats, barley, potatoes, lentils, soybeans, and alfalfa, but also heirloom seeds and forgotten landraces. Boxfuls of foraged grasses are stored cheek-by-jowl alongside sorghum, foxtail millet, bur clover, purple bush-beans, pigeon peas, Kentucky bluegrass, and creeping beggarweed. Every country in the world is represented, as are several countries that no longer exist. Colombia, North Korea, Russia, Taiwan, Ukraine, Switzerland, Nigeria, Germany, Israel, Syria, Zimbabwe, Tajikistan, and Armenia share shelf-space in this pastoral League of Nations. With over 90 million seeds deposited in the bank, India represents the largest crop diversity, nearly three times as much as Mexico, the next most prolific contributor.

On February 26, 2008, the day the seed vault opened, Pakistan and Kenya were first in line to store their seeds. The previous year, the disputed election of Mwai Kibaki in Kenya triggered ethnic violence against Kikuyus. Karachi had catastrophically flooded and was scene to a bloody suicide bombing, and Benazir Bhutto was assassinated in Rawalpindi. One can speculate that, for Kenya and Pakistan, a cache in the Seed Vault is a way to refuse political and climatological vulnerability — to forecast a future that might, somehow, sustain life.

One shelf of the vault is half empty. Four years into the civil war and humanitarian crisis in Syria, violence barreling northward toward Aleppo jeopardized the Headquarters of the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA). Hundreds of thousands of seeds were banked here in Svalbard, including some of the earliest strains of Levantine wheat and durum, which are more than 10 thousand years old. The Syrian gene bank, now relocated to Morocco and Lebanon, recently requested 30 thousand samples from its original collection to help rebuild the country’s stores of barley, lentils, and chickpeas.

After an hour in the vault, my hands have become dumb appendages in a worryingly cadaveric shade. The cold has muscled through the seams of my coat, and my camera died within minutes of entering vault #2. Fowler and I retrace our steps and head back outdoors.

Standing at the edge of Platåberget mountain cast in perpetual twilight, Fowler marvels at the irony: “We’ve got the largest collection of agricultural biodiversity in the world here, where there aren’t any farms or gardens or trees or even an outdoor plant.” I nod in response, because here, on the surface of things, it seems as if nothing is alive. Yet Platåberget teems with subcutaneous life, paused and sedimented into the mountain’s warped and overlapping temporalities in a state of deferred potential. Here, some life is slower than molasses on a snow day, and some is stuck firmly in the past. But much of the latter is uncannily durable, perpetually present in the present. It lags; it persists. It promises to last forever, even as it is endangered. It can be patient as a saint, and quiet to the point of cryptic. Yet these temporal distortions, like those in Yamalo-Nenets, are climatological: time is tuned to temperature. And the temperatures are rising.

¤

¤

[1] Excerpts from this section were previously published online as “Ruin" in Theorizing the Contemporary, Cultural Anthropology website, September 30, 2016 (available here: https://culanth.org/fieldsights/959-ruin). Reproduced courtesy of Cultural Anthropology.

[2] Elin Andreassen, Hein B. Bjerck, and Bjørnar Olsen, Persistent Memories: Pyramiden -- A Soviet Mining Town in the High Arctic (Trondheim, Norway: Fagbokforlaget, 2010), 142.

LARB Contributor

Sophia Roosth is the Frederick S. Danziger Associate Professor in the Department of the History of Science at Harvard University. Her research focuses on the 20th- and 21st-century life sciences, examining how biology is changing at a moment when researchers build new biological systems in order to investigate how biology works.

Roosth was the 2016 Anna-Maria Kellen Fellow of the American Academy in Berlin and in 2013-2014 she was the Joy Foundation Fellow of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. She was previously a postdoctoral fellow at the Pembroke Center for Teaching and Research on Women at Brown University and a predoctoral fellow of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin. She earned her PhD in 2010 in the Program in History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology, and Society at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Roosth has published widely in journals including Critical Inquiry, Representations, Differences, American Anthropologist, Science, and Grey Room.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Climate-Anxious Late Environmentalism

"Green Planets" takes as its starting point the fact that we and everything else that lives on/in/through planet Earth are in a lot of trouble.

Is There Still Hope?: A Climatologist’s Perspective

Will we tackle this problem in time?

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fdev.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2016%2F12%2FRoosthArctic-1.png)