Violent Revelations: On Heather Lewis’s “Notice”

Emmeline Clein reviews the reissued edition of Heather Lewis’s “Notice.”

By Emmeline CleinApril 4, 2024

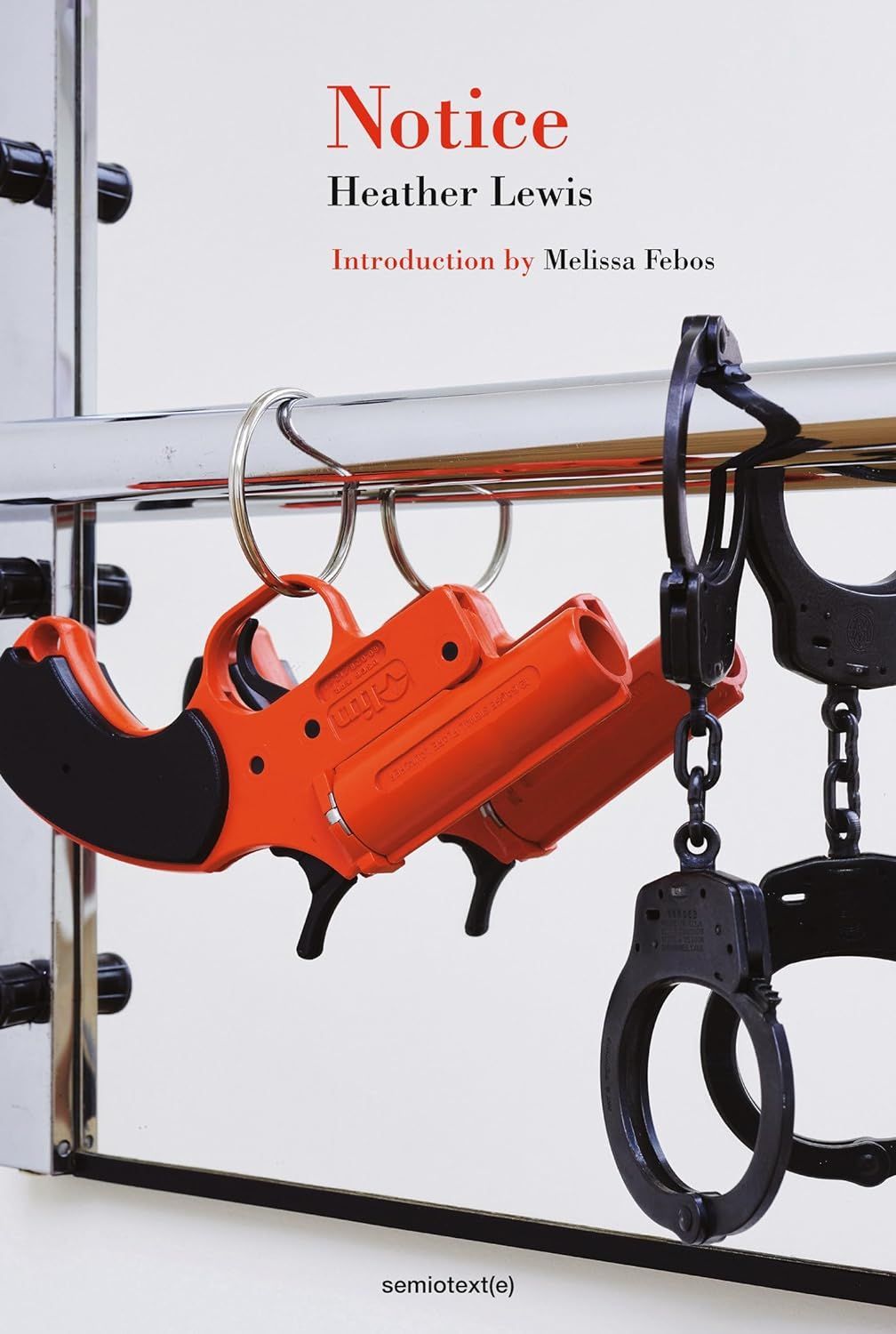

Notice by Heather Lewis. Semiotext(e). 248 pages.

TO NOTICE is revelatory. It’s also violent. To be on notice is to know that already, to bear a body inscribed with knowledge’s scars. To put someone else on notice is a threat as often as it’s an attempt at protection: eviction notice, hazard notice, final notice.

Is this the most disturbing book you’ve ever read? A Reddit user is desperate to know. Crime novel YouTuber @CriminOlly has an answer, definitively calling Heather Lewis’s Notice “The Most Disturbing Book I Have Ever Read.” According to Goodreads reviewers, it’s “human brutality laid bare in its purest form”; a “tough, bleak read”; “another level of horror”; “so raw and distressing I’m not sure [I] could recommend it to anyone.”

Notice was first printed by Serpent’s Tail in 2004, two years after Lewis’s death, and has been reissued this spring by Semiotext(e). “Brace yourself,” Melissa Febos writes in her own bracing, brilliant introduction to the new edition. This is a novel that puts you on edge from its first scenes. It elicited similar reactions when Lewis first sent out the manuscript: according to her friend and former mentor Allan Gurganus, it was “adjudged too dark and disturbing” by the 18 different publishers who turned it down.

The novel Notice follows a young sex worker, known as Nina to her johns. Lewis turns as many rhetorical tricks as her protagonist, and this is the first: by refusing readers any name but the one she offers those men, we’re immediately rendered johns too, paying to play and exploiting pain, sparking questions about “trauma porn”—is this the most disturbing book you’ve ever read? Isn’t autofiction an exercise in sadomasochism, after all?

Am I getting ahead of myself? If I am, it’s because this book gutted me and played me and broke my heart, invented a game of truth or dare that was also a round of Russian roulette, ran a race with no warning shot. The prose laps me even now.

Let me try to tell you what I mean. The three novels Lewis wrote over the course of a career cut short by suicide trace trauma—sexual, physical, emotional. They lay bare battered limbs and a bruised heart, the body of work that survived when the woman who produced it couldn’t. In his afterword to the first edition of Notice, Gurganus called his friend a “prophet of the test crash, and, therefore, a professional casualty.” Her stories are rife with falls, collisions, pummelings; people who keep getting up and going back for more; hurt women with access to powerful painkillers, seduced by the void, staring into despair, desperate yet tender at heart—and to the touch. This is where her work wants to take us, against all odds: into another woman’s arms. Hold on tight.

¤

A cross-dressing fifth grader sips an ice-cold glass of vodka after a long day of school. Her father will get caught up in Watergate around the same time she gets caught doing drugs with boys. Exposure follows exposure, which is followed by conversion therapy, incarceration in psychiatric institutions, incest—rebelling against the hedge-rimmed suburb she grew up in, learning early to hedge her bets. Adults can’t be trusted; children like Lewis and her autofictional protagonists have no time for innocence. They manage to maintain some nonetheless. There is “this place in me that felt early, as in ancient, but still very young,” the narrator of Notice observes, on her back in the arms of a woman she loves, who she is letting touch her despite how many times already touch has turned to terror over the course of her brief life. She is listening to the woman tell her things “that couldn’t possibly be true but which [she] wanted to hear”: that she means something, that she made a difference, that she saw something others hadn’t.

Lewis’s own life mirrored those of the protagonists in her three novels—House Rules (1994), The Second Suspect (1998), and Notice—who can each be read as one woman at three different points in her life. Those who loved Lewis found the parallels between her and that woman harrowing; in his remembrance of his mentee, Gurganus wrote of a “wish to believe [her work was] happening solely on the level of Allegory,” while Febos observes that “even many of Lewis’s close friends couldn’t stomach the book.”

While Lewis’s life was brief, it was also vibrant, ablaze with feeling. Her blood ran hot, so to survive she let her voice go cold. Her prose iced into stalactites; her words became weapons of murder and vigilante justice. Her oeuvre is rife with inverted, feminized holy trinities: trauma, terror, and tenderness; mother, daughter, and lover. I’m not leaning on sacred language for style; I’m using it because Lewis’s sex scenes are crucifixions, her depictions of syringes slipping into veins are resurrections, her bruised embraces are seances. The narrator is a holy ghost. She has seen too much, is gone too soon, has sold herself for a story and some solace on a dark night—which turns out to be most nights for her protagonists. For Lewis’s readers too, if we’re honest with ourselves. Which is why her work winds you. Knocks your breath out like falling off a horse or being hit in the face, both of which happen, often, to her characters.

¤

Like I said, I’ll try to tell you what this book is “about.” Be on notice, though: nothing I write here will prepare you. This saves me from the necessity of inserting spoiler alerts, but then, this book is an elegy for fruit left to spoil instead of sliced up and savored. It’s the sparkling edge of a storm cloud, lightning striking so many times in a row it feels like fate—or maybe just fiction.

As I’m sure you can tell, I’m struggling. I want to do this novel justice, but it burns when I touch it. Lewis wasn’t afraid to put her whole palm on a hot stove. I’m not so brave, not numbed or blunted or fearless.

Let me try again.

¤

In her contribution to A Woman Like That, a 1999 anthology of lesbian and bisexual coming-out stories, republished in zine form by Semiotext(e) alongside this novel, Lewis begins by ripping the closet door off its hinges. “I never thought of myself as ‘in’” she writes, “as in: in the closet, in hiding, incognito. If I was any of the ‘ins,’ the only one that fit was indiscreet.”

Playful, ominous, sidestepping the noir to find light where you least expect it, her sentences startle. Lewis began sleeping with women before she was 10, then turned tricks in her teens. Her wealthy parents didn’t pay much attention to all this, distracted behind suburban hedges by her father’s professional downfall. “Caught,” Lewis muses, “might be the right word” for what happened to Richard Nixon, whom her “father’d gotten in tight with,” but it wasn’t for her: “Noticed was more like it.” Yet capturing her father’s notice led the writer right into a series of predatory and vindictive traps—ones that Notice’s protagonist ends up mired in too.

Lewis endured conversion therapy and carceral mental institutions, a trajectory mirrored by the narrator’s harrowing journey through a local jail and an asylum, and puppeteered by an especially powerful john likely modeled, at least in part, on Lewis’s own father. For character as for creator, systems and spaces ostensibly intended to offer refuge and healing reveal themselves as instruments of an oppressive power structure. In them, syringes hold paralytics as often as painkillers. Hospital beds hide handcuffs. Wandering asylum halls among women who underwent lobotomies and electroconvulsive therapy, the narrator notes that “this wasn’t a place where people got better. This was a holding pattern and these women holdovers.”

Lewis and her protagonist do make it out, with the help of a therapist and lover who might be taking advantage of a vulnerable girl but also might just be in love with her. Lewis is a deft cartographer of the relational black hole; she has a finger, always, on the catch in the lock. What I mean, to borrow Febos’s incisive phrasing, is that she writes about “the love of a woman who fails to protect her.” Lewis describes her own predilection for passing as someone she’s not, playing “surrogate daughter, lover, confidante” to escape the violence of her childhood home, even as it led her into other catch-22s.

Freedom comes with a cost, as does truth. “The cover story of all time, that’s what money is,” Notice’s protagonist muses as she considers her decisions, her choice of profession: “The excuse of excuses no one will question because they so much need to use it themselves.” But she’s not fooling herself; she knows there’s another reason she seeks out experiences that scar, people in pain, men who get off on inflicting it. After getting tangled up in a sadomasochistic sexual triangle with a wealthy murderer and his ghostly accidental accomplice of a wife, she cycles through a series of violent situations, entrapped by alternately earnest and exploitative women falling fast down their own escape chutes.

Of course, Nina tries to pad their landings or grease their paths. She has given up on finding safety for herself yet stumbles lurchingly through her yearning for it, doing what she can for other women. “Not much else was asked but to be who she needed me to be, which was exactly the thing I’d been born” to do, she muses, reflecting on one such relationship.

¤

“You understand, right?” Nina asks us in the end. “How I could land on my back and just lie there? From that position, it’s hard to make sense of things. Hard not to get caught up in someone telling you the things you’ve wanted to hear your whole life, and so does it matter if what they’re saying is true?” Hard falls, nine lives, so many lies. She has picked up on nearly everything most of us are afraid to acknowledge, let alone say aloud, and these slippages into second person indict and accuse us. We fear notice.

And then there’s the other type of notice, the one born of care, the kind we take of the people we love. This, I think, is the real subject of Notice and the rest of Lewis’s work: the agony of yearning for someone else’s eyes, the devotion of attention, the gazes that cross and untie knots you’d never seen on your own. The first night Nina spends with the couple that almost kills her, the man’s violence veers unexpectedly toward his own wife, and the narrator flinches, fights back on her behalf. “He’d paid me enough to do it to me, but not to watch him do it to her,” she thinks. It’s a move the narrator makes often, shouldering the pain of others because she believes she can handle it, because she thinks others won’t notice how much pain she’s in herself.

¤

Most critical accounts of Lewis’s writing wax poetic about her dissociated tone. Her chilly accuracy and deadpan delivery of violence and violation are praised; comparisons are drawn to Hemingway. The accolades are deserved: Lewis wields her pen with the precision of a scalpel. (Vitally, Febos draws out the dichotomy between millennial fiction’s dissociated, privileged protagonists—whose numbness is “an affect, a style”—and Lewis’s narrators, who are “cool and detached because the only alternative is to go up in flames.”)

Yet obsessing over her prose’s apparent nonchalance obscures the anguish shuddering just beneath the surface. Her women try to ventriloquize overwhelming emotion into sex: “[I]nstead of letting it up,” explains Nina, “I pushed it down. I put it into my belly and then lower until it could be all about pressing against her.” These women have shifted gears, “gone on automatic.” But neglected bruises are still tender to the touch. “I wanted to feel deadness or at least hatred but instead could only feel loved,” Nina realizes, in the arms of a woman who couldn’t or wouldn’t protect her but seemed to want to save her, and at the very least saw her.

Dissociation by way of drugs or sex only leads to more feeling. Even in contorted, convulsive relationships—ones that approach the sororal before becoming sexual, eventually bending into the maternal until, finally, something like friendship emerges—Lewis’s narrators reveal and recognize their capacities for care, both toward others and themselves. For the narrator of Notice, one such affair leads to places she “didn’t want to go, but had to.” What she “found there wasn’t ugly, not exactly. Messy and massive, monstrous even, but not evil, more a behemoth than a demon.”

What Nina discovers is her own nascent longing, lurching around inside her until at last it arcs out, finding another woman. With that woman, she recognizes a “feeling” that “bathed that hulking place that’d been so sore, sore from my very beginnings.” Crying, finally, in the other girl’s arms, her shuddering body becomes “quiet and ageless,” “hushed and tranquil and endless.” As much as she tried to masquerade as a numb girl in a hardboiled noir, she had always known in that sore, ancient place, what she needed—“help in the most conventional of ways.” Notice thereby reads as Lewis’s precarious attempt at a kind of self-mothering—the book a broken umbilical cord, tied to a helium balloon.

¤

I wish Lewis lived longer and wrote more. What she left behind beckons and blisters, burns with yearning, and steers us, slowly, toward tenderness—even as its author hurtled somewhere most of us have never been brave enough to venture. Mercifully, she found the occasional, gentle reprieve: a few nights of sleep, a stretch of sunny days. I want to end on those, in the words Lewis put in a gentle teenager’s mouth, on an era that ended but nonetheless happened, days when she took deep breaths and saw something like serenity: “I began living in a quiet way. I did this suddenly. But at the same time, I’d slipped so silently into it, I might never have noticed. Except, lately, this type of thing was all I did notice.”

LARB Contributor

Emmeline Clein’s first book, Dead Weight: Essays on Hunger and Harm, is out now from Knopf. Her chapbook Toxic was published by Choo Choo Press in 2022. Her essays, criticism, and reporting have been published in The Yale Review, The Paris Review, The New York Times Magazine, and other outlets.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Catharsis Isn’t a Dirty Word: A Conversation with Melissa Febos

Lilly Dancyger interviews Melissa Febos about her upcoming craft book on personal writing and publishing, “Body Work: The Power of Personal Narrative...

A Queer Reading List from LGBTQ-Identified Authors at the PDX Book Festival

Sarah Nielson breaks down some of the discussions going on among LGBTQ writers at the PDX Book Festival in November, as well as some recommendations.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!