Unthinking the Family in “Full Surrogacy Now”

Madeline Lane-McKinley considers Sophie Lewis's new book, "Full Surrogacy Now: Feminism Against Family."

By Madeline Lane-McKinleyJune 10, 2019

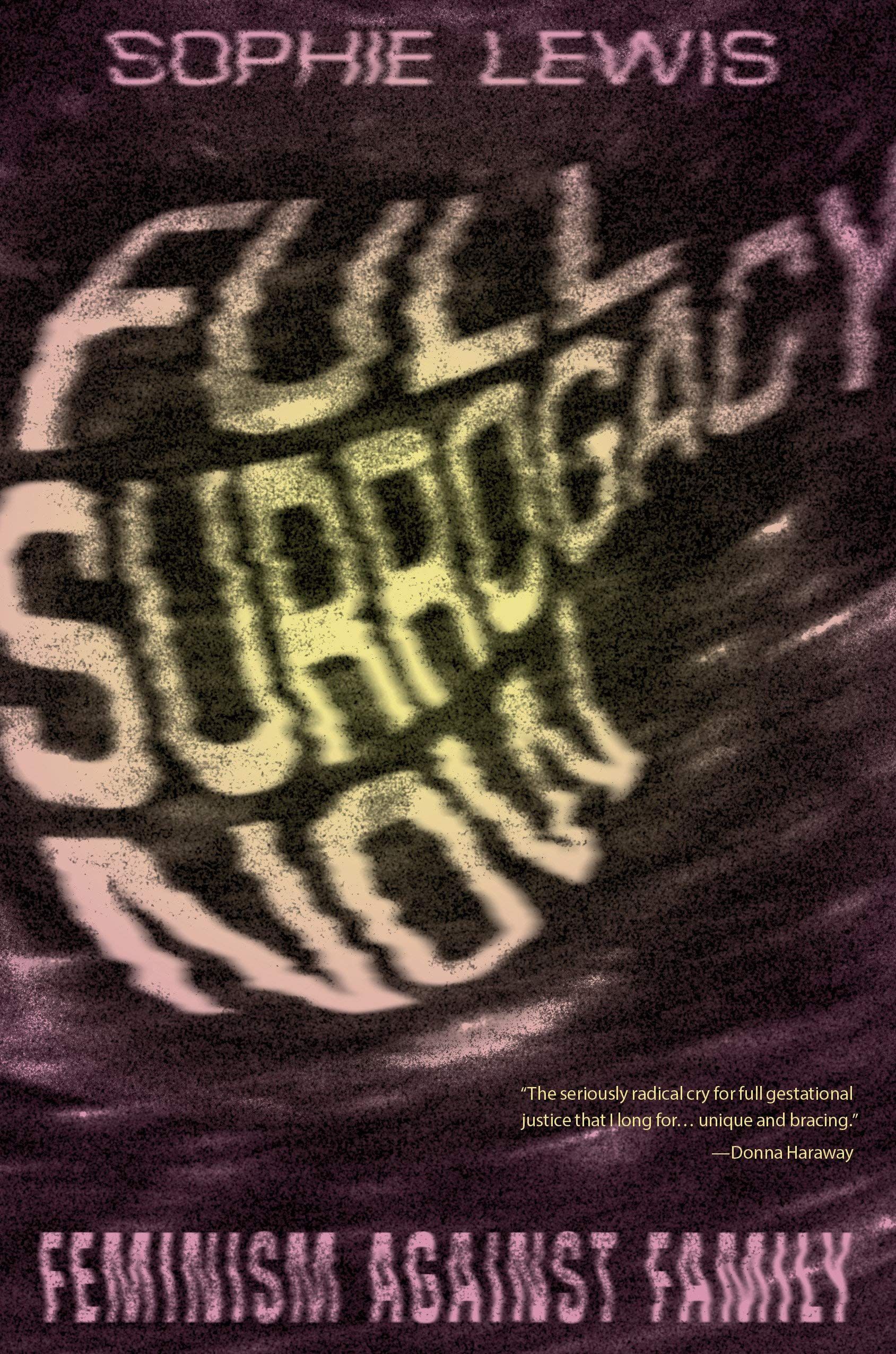

Full Surrogacy Now by Sophie Lewis. Verso. 224 pages.

“REALISM” — AND ITS attendant demand for plausibility, imaginability, and appeals to common sense — taunts a version of feminist history. “Softhearted and softheaded,” feminism has been perennially recast, Kathi Weeks suggests, as “more precisely, softheaded because softhearted” — like utopianism, it is “at best naïve and at worst dangerous.”

As doomed to such rebukes as any other text of its ambition and political scope, Sophie Lewis’s Full Surrogacy Now anticipates and thoroughly rejects this anti-utopianism that — specifically through gender — fancies itself somehow “realist.” Her debut text is a more properly historical materialist case against this “realism” on the one hand, and something of a science fiction on the other. Without naming itself as such, Full Surrogacy Now is a manifesto. And in the spirit of Donna Haraway’s A Cyborg Manifesto, it explores a multiplicity of feminisms and possible futures, through vibrant moments of genre-bending, speculation, and immanent critique. Provocatively, and with an often wicked sense of humor, Lewis historicizes and taunts back that which renders her project seemingly impossible, modeling (as her subtitle promises) a “feminism against family.”

The speculative future staged by Full Surrogacy Now is that of family abolition. As an addendum to Fredric Jameson, Lewis conjectures that “it is still perhaps easier to imagine the end of capitalism than the end of the family.” Certainly, the thought stimulates a wide range of frustrations and anxieties, along with the familiar proclamations of hysteria. Recalling a 2014 conference in London, for instance, Lewis describes an unnamed speaker in strong opposition to family-abolitionist thought: “We are not,” the speaker cried out, “about to march around with placards saying ‘Abolish the Family,’ which would be crazy.”

Inspiringly, Lewis’s critical utopian impulse is to face up to this “crazy.” The supposed craziness of family abolition is not so much challenged as profoundly integrated into the problem around which Full Surrogacy Now orbits: primarily, the problem of its own imaginability.

Of course, the thought of family abolition is crazy — and to sit with it is crazy-making. As Lewis makes clear, it is a matter of bumping up against, rather than shutting down, our capacity to even think, much less collectively enact, revolutionary struggle. Through these productive and often painful frictions with “realism,” the text “stands for the levelling up and interpenetration of all of what are currently called ‘families,’” Lewis asserts, “until they dissolve into a classless commune on the basis of the best available care for all.”

In this framing of a feminism against family, Full Surrogacy Now understands the work of “baby-making” precisely as work, ultimately asking of the possibility for all baby-making to be reimagined, through revolutionary comradeship, as surrogacy. Always in contrast to Surrogacy™ — the commercial surrogacy industry which generates an estimated one billion dollars a year — “full surrogacy” is a queer communist speculative future: “We are the makers of one another,” she writes, “And we could learn collectively to act like it. It is those truths that I wish to call real surrogacy, full surrogacy.”

Never hiding from full surrogacy’s lurking sense of unthinkability, Lewis calls for a mode of thinking about family abolition through an ongoing friction with nihilist visions of withdrawal, negation, or abandonment. “Couldn’t there be more (rather than less) opportunity for bonding and connecting,” she asks, “in a surrogacy context?” However “crazy,” her version of the end of the family is not at all the end of care. Rather, “full surrogacy now” takes the standpoint of a “plural womb and a world beyond propertarian kinship and work alienation.” As Lewis maintains, this is not the end of care but the beginning of real care.

To today’s Marxist-feminist focus on social reproduction, this demand for full surrogacy marks a crucial contribution: a “multigender feminism in which the labor of gestation is not policed by well-meaning ethicists but, rather, ongoingly revolutionized by struggles seeking to ease, aid, and redistribute it,” as Lewis describes it. The question of “life-making,” which Tithi Bhattacharya and Susan Ferguson raise in defining social reproduction theory, might be elaborated through this expansionary theory of surrogacy. The term “surrogate,” Lewis suggests, has the potential to bring together millions of precarious and/or migrant workers — gestators along with, to start, “cleaners, nannies, butlers, assistants, cooks, and sexual assistants” — whose work “is figured as dirtied by commerce, in contrast to the supposedly ‘free’ or ‘natural’ love-acts of an angelic white bourgeois femininity it in fact makes possible.”

In a moment charged with feminist revivalism, as well as competing and recuperative feminisms, Full Surrogacy Now is as much a demand of the impossible as a meditation on radical disinheritance. “Wanting a mode of gestation that itself contributes to family abolition makes my little book a clear descendant of disparate elements of the Second Wave,” Lewis acknowledges playfully, while calling the text a “disloyal, monstrous, chimerical daughter indeed.” Not only de-centering but fully eradicating the mother-child relation from how she conceptualizes gestation — that is, as labor — Lewis is consistently disloyal, to borrow her own phrasing, to the feminist theorists who made her work possible. She does not abandon but, in Haraway’s terms, she “stays with the trouble.” It is a loving disloyalty, seeking to unimagine, in broader terms, the labor of love. It is also a source of enduring conflict and ambiguity.

Among her disloyalties, Lewis finds fault with Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex (1970) and Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time (1976), calling both texts “insufficiently ambitious” in their determination to wish away the labor of gestation in search of what she describes as a “gestational fix.” In each case, she suggests, the problematic of pregnancy — whether figured as labor, love, nature, et cetera — is estranged and displaced, rather than fully dealt with. As Lewis observes of Firestone, what will be unfortunately most remembered of her “flawed masterpiece” is the proposal that “childbearing … be taken over by technology.” Quite powerfully, Lewis launches a consistent attack on the trans-exclusionary implications of Firestone’s work, as well as Piercy’s, both of which trade in biological determinism in differently problematic ways. Throughout the text and elsewhere, Lewis challenges trans-exclusionary radical feminism (TERF) as a dangerous and conservative strain in the battlefield of contemporary feminisms.

Staging direct confrontations at several instances in her text, Lewis models for us a way forward which takes on the radical kinship at stake in “full surrogacy” — not of canceling, forgetting, or forgiving, but of troubling. Reading Firestone’s utopia against the grain of her political theory, Lewis recovers the most revolutionary elements from The Dialectic of Sex as well. Most evocatively, Full Surrogacy Now continues Firestone’s often overshadowed dream of collective belonging, outside the terms of the mother-child “social bond,” and through the abolition of the capitalist family.

Entering into a love-hate relationship with Firestone is something of a rite of passage — and for this, I appreciate Lewis’s nuance and care, never at the cost of critical rigor. After publishing The Dialectic of Sex, with severe anxiety, at the age of 25, Firestone only published one more book, 28 years later, after years of institutionalization — not uncommon in her Women’s Liberation cohort. Certainly, there is an exhaustive list of low-hanging problems to pull at in The Dialectic of Sex: Firestone’s contribution to “sex class” theory, her appeals to nature, and her optimism toward technology are among the many. But what I have grown to feel about The Dialectic of Sex — which is perhaps more apparent in Firestone’s later work, Airless Spaces — is that its antagonism toward genre has been tragically overlooked if not misread. What she perhaps felt had to be framed as a grand synthesis of “feminism” with Marx, Engels, and Freud, becomes ultimately something more akin to the work of Charlotte Perkins Gilman: a feminist utopian thought experiment, which she describes as “the case for feminist revolution.” This mutiny against genre is something that Full Surrogacy Now shares in common with this flawed masterpiece from 1970, and quite knowingly.

Lewis has a much keener sense of her genre trouble than Firestone. While Lewis promises her text will not be a matter of case studies, she offers plenty, along with autobiographical interludes, theoretical conjectures, forays into various debates and generative conflicts. Fluidity is hardly to be missed as a motif that especially comes to life in her conclusion. Noting that “all humans in history have been manufactured underwater,” Lewis postulates that “[o]ur wateriness is our surrogacy. It is the bed of our bodies’ overlap and it is, not necessarily — but possibly — a source of radical kinship.” In these musings on wateriness, she offers a hermeneutic for the text.

It is no coincidence that some of the primary texts Lewis draws from are in some manner science fictions like hers. Besides Firestone and Piercy, Octavia Butler and Ursula K. Le Guin are crucial influences, alongside Haraway, Angela Davis, Mary O’Brien, Simone de Beauvoir, to name only a few. As Lewis reflects, “While the name on the cover of this book is mine, the thoughts that gestated its unfinished contents, like the labors that gestated (all the way into adulthood) the thinkers of those ongoing thoughts, are many.” Yes, the process described here is no different from any other text: there is never a “mine,” and there is always a “many,” though often unacknowledged. What is different, however, is how Full Surrogacy Now here and elsewhere actively seeks to be communized and de-individuated as a collective project — not as the “death” of authorship (or private property) but as its complete abolition. Just as Lewis asks us to unthink the proprietary bond between gestator and child, she begins to construct an epistemology of surrogacy, at points brilliantly elaborated through this analogy of motherhood and authorship.

Fittingly, and from the start, one of Lewis’s central antagonists is Margaret Atwood. In her reading of Gilead, Atwood’s reproductive dystopia in The Handmaid’s Tale, Lewis argues that “human sexuation is neatly dimorphic and cisgendered,” adding, “but that is apparently not what’s meant to be dystopian about it. It’s the ‘surrogacy.’” The “universal” agony at the center of Atwood’s narrative is the separation of a mother from her daughter, and moreover, the breeder’s deprivation of motherhood. Lewis is not alone in reading The Handmaid’s Tale as a deraced slave narrative, tending toward a version of “cisgender womanhood, united without regard to class, race, or colonialism, [that] can blame all its woes on evil religious fundamentalists with guns.” However, far more than taking up these questions in the 1985 novel, Lewis targets the narrative’s resurgence as what today’s cultural feminist front claims to be an “allegory of our times” in the Trump era. To the alarum “We are living in The Handmaid’s Tale,” she retorts, “People’s eagerness to assert that we are betokens nothing so much as wishful thinking,” in that “it promises that a ‘universal’ (trans-erasive) feminist solidarity would automatically flourish in the worst of all possible worlds.” It is in this sense, as Lewis suggests, that “the dystopia functions as a kind of utopia: a vision of the vast majority of women finally seeing the light and counting themselves as feminists because society has started systematically treating them all — not just black women — like chattel.”

These Atwoodian anxieties get us closer to understanding white feminism’s humanitarian impulses, as in the anti-surrogacy campaign, Stop Surrogacy Now, which Lewis detourns like much else. Contending with these anti-surrogacy and anti-sex work platforms, Lewis argues that these political rhetorics have been used to justify imperial wars and establish a “rescue industry,” seeking to “abolish the commodification without abolishing the work.” Entangled, quite generatively, in this analogy between sex work and surrogacy, which Lewis takes on as anything but simple, she redirects us toward the abolition of work: “All we really know is that their articulation as work in the first instance will be key to abolishing them (as work) in the long run.”

¤

What’s most frustrating about Full Surrogacy Now is also what’s most remarkable about it: how it lingers with the discomfort induced, so thoroughly, by the unimaginable. Throughout, Lewis demonstrates how the revolutionary possibilities of “full surrogacy” and family abolition can merely be grasped at, precisely because of the dystopia we find ourselves in. Where Lewis might slip easily into programmatism or reform-based solutions, she perseveres instead toward a troubling of her own language and key concepts, animated all the while by a sense of futurity. The work of this project, as she notes herself continually, is necessarily collective — and whether this project is to be continued is yet to be determined, but the prospects are good. Queer communist Jules Joanne Gleeson, for instance, has delved into the possibilities of this text already, not only underscoring Lewis’s commitment to a trans-inclusionary view of gestation, but asking of the “presently unclear relation” between this work on womb-labor and Marxist-Feminist thought in social reproduction theory.

Like Gleeson, I can’t help but hope that “Surrogacy” could bring together some of the more disparate yet potentially congruent “feminisms” today. Yet to the extent that Full Surrogacy Now could provide such a point of synthesis, it is likewise, quite clearly, something of an outsider text. Perhaps too occasionally, Full Surrogacy Now features moments of approximating and making concrete the possibility of its fundamental demands. “We need ways of counteracting the exclusivity and supremacy of ‘biological’ parents in children’s lives, experiments in communizing family-support infrastructures; lifestyles that discourage competitiveness and multiply nongenetic investments in the well-being of generations,” she writes, fully attuned to the rebukes of “realism” she finds herself taunting back.

These more practical moments are gestures throughout Full Surrogacy Now toward what is not-yet-conceivable, all with a built-in sense of urgency, potentiality, and familiar sorrow. Like Butler, Le Guin, or Samuel Delany — queer, feminist, anti-colonial writers, prone to science fiction precisely as a mode of abolitionist dreaming, untethered from chauvinist “realism” — Lewis pulls to the surface of her text ideas and desires that cannot survive with us here, in this toxic atmosphere. But these longings for “a world worth living in,” as she forcibly unravels, demand from us more than a moment of thought.

¤

LARB Contributor

Madeline Lane-McKinley is a writer and a founding editor of Blind Field: A Journal of Cultural Inquiry.

LARB Staff Recommendations

The Free Labor Force of Wives: A Conversation with French Feminist Writer Christine Delphy

Annie Hylton talks to French feminist Christine Delphy about domestic labor and #MeToo.

Your Child, Your Choice: How the United States Made Parenting Impossible

How the neoliberal rhetoric of "choice" has made it harder to raise children.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!