Under the Tyranny of Memory

Memories of the Soviet Union haunt Ukrainian author Serhiy Zhadan's recently translated novel, "Voroshilovgrad."

By Amelia GlaserJune 29, 2016

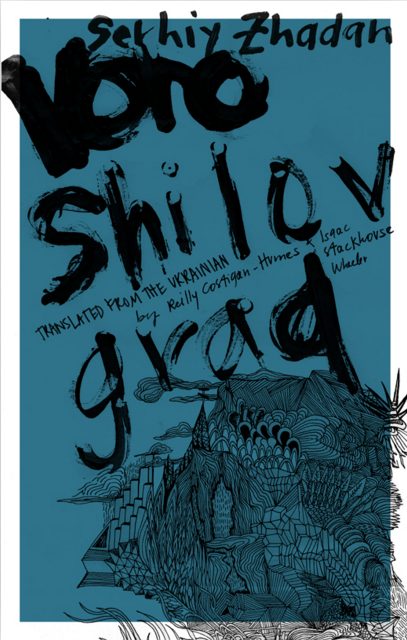

Voroshilovgrad by Serhiy Zhadan. Deep Vellum. 400 pages.

THERE IS A PACKET of postcards depicting the Soviet city of Voroshilovgrad in Serhiy Zhadan’s novel of the same title. Olga, one of the novel’s lonely protagonists, remembers sending them to her German pen pal during her Soviet school days. “I’d buy whole sets of them. I’d pick out the ones with tons of flowers because I wanted him to think that Voroshilovgrad was a fun city. I would just keep all the other ones, with all the monuments and stuff.”

Voroshilovgrad, which reverted to its earlier name, Luhansk, in 1990, is the administrative center of a large section of Donbass, Ukraine’s easternmost region, bordering Russia. The characters in Voroshilovgrad are so disenfranchised that they live in the suburbs of a city that exists only in their memory. They kill time. They fight. They drink bad alcohol. They occasionally kill each other. And yet they remain attached to their hometown, guarding their childhood memories with their lives.

The main protagonist, Herman, has left his unnamed hometown for Kharkiv, where he earned a degree in history, and where he holds a decent job ghostwriting government speeches. He lives with a friend and employer, a shady businessman from whom he hides money, appropriately but unsuccessfully, in a volume of Hegel. But the novel resists Hegelian dialectics, taking Herman, instead of forward toward progress, into a nonlinear realm of memories and other people’s dreams. He is spirited back to his hometown after the disappearance of his brother.

There, he takes charge of his brother’s gas station, a task that involves not only keeping cars supplied with fuel, but protecting the station from Pastushok, a local Communist Party member and corn baron who has already bought gas stations across the Donbass. Although it isn’t clear to anyone, least of all himself, why Herman feels so invested in fighting Pastushok’s “corn guys,” he stays on — leaving his job, cutting his ties to his city friends, sleeping with the lonely women of greater Luhansk, and letting his own memories intertwine with those of his brother, his friends, and his lovers. The novel is, on one level, a meandering story of one individual learning the meaning of friendship and coming to terms with his past. On another level, it is a portrait of the Ukrainian-Russian borderlands, neglected by all but its hardened residents since Ukraine declared its sovereignty in summer 1990.

Serhiy Zhadan is a pop culture icon in his own right, and his contributions have been increasingly important as violence has consumed his native Eastern Ukraine. Born, like his protagonist, in a suburb of Voroshilovgrad, he earned a degree in philology at Kharkiv University and briefly taught Ukrainian and world literature. He gave up teaching literature to write, translate, and front a rock band. He won the BBC Ukraine’s Book of the Year Award twice: in 2006 and 2010. Zhadan played an active role during the 2004–’05 Orange Revolution and then again in the 2013–2014 Euromaidan protests against corruption in Viktor Yanukovych’s government. He was among dozens of pro-Western demonstrators who were badly beaten in a violent clash with pro-Russian demonstrators in Kharkiv; news of his hospitalization quickly spread across traditional and social media. Zhadan later wrote on his Facebook page that, when asked to kiss the Russian flag, “I told them to go fuck themselves.” A few weeks later (and three years after the novel was published), Zhadan’s home region became the center of a major international crisis: the rebels declared it the “Luhansk People’s Republic,” adding another layer of trauma and turmoil to the already painful memories.

Zhadan, who speaks both Ukrainian and Russian, is making an important political statement by choosing to write literature in Ukrainian. And yet his literary subjects cannot leave their Soviet past behind. Products of a contentious border region, these characters fight to understand and even to defend their collective memories, which have been subject to perpetual political and cultural erasure. Maurice Halbwachs wrote of the importance of “place and group [which] have each received the imprint of the other.” Shared memories and a shared space connect Herman and his friends, even if this space is one of “emptiness without content, form, or connotation,” as one character puts it.

All characters in the novel struggle to hold on to their history. When Herman asks one of his love interests, a woman “already well over the hill,” whether she sees a future for herself in the valley, she answers: “No, […] But there’s a past. The past can also make you stick around.” Herman’s friend Kocha, an insomniac who works at the filling station, tells stories of improbable exploits with women and petty thieves. Another friend and co-worker, a pretty boy and former local soccer star called Injured, is an aging local hero who can still score a goal when need be. Ernst, a former history major like Herman, now spends his days digging up World War II remnants of German fascism, drinking in the city’s defunct airport, and agitating for its revival. A presbyter whom Herman meets at a funeral carries around — in place of a bible — an old beaten copy of a scholarly book on the history of Jazz in the Donbass. “What does death teach us?” wonders the presbyter in his eulogy. “[T]hat we must remember everything that has happened to us and to those closest to us. That’s the main thing. Because when you can remember everything from your past it’s not so easy to let go of it.”

The enigmatic statement might well sum up Zhadan’s poetic portrait of a no-place, which emerges in layers of memories, dreams, and longings. The wasteland where most of the novel unfolds is home to abandoned factories, the dead airport, and a shallow river. It’s often filled with a fog that blends with the characters’ reveries. “The remaining darkness had settled on the bottom of the valley like silt. Here on the hill, the air had filled up from the inside with white fog.” Ghosts, fantasies, and local hoodlums keep wandering through this ever-present fog.

Some of Zhadan’s representations of history and memory are over-determined. In a final showdown between Herman’s friends and the “corn guys” over the filling station, two rivals’ reveries become entangled. One character remembers humiliation about his latent homosexual desires; the other remembers an equally transformative heroic moment of heterosexual triumph. The psychologisms become a bit heavy-handed:

His whole family was the same — his whole greedy family. His mom didn’t have any sense of camaraderie, and neither did his dad. Nothing — not even active involvement in the Communist Youth League and a management position, which he finally achieved — could make him feel like less of an outsider.

With this descent into Freud, Zhadan seems to suggest that his characters’ private lives cannot be separated from the politics of their disputes; the trauma of memory in the Donbass ranges from psychology to geopolitics.

One memory, in particular, torments Herman. He tries, throughout the novel, to remember a victory party in summer 1990, after a soccer game against Voroshilovgrad:

It was evening, and we were celebrating the victory: our players as well as local gangsters, women wearing fancy dresses and men wearing white dress shirts or track suits, waiters — budding capitalists, all of us, sitting together with all kinds of crooks, hot waves of alcohol breaking over our heads. It made me think of when we’d dare each other to run into the sea at night: a bittersweet, black wave washes over you and then you run out onto the beach, a man, not a boy.

This heady coming-of-age summer is, of course, also the coming of age of independent Ukraine, and the end of Voroshilovgrad. This partial memory accompanies the gnawing sense that life’s greatest moment might be behind Herman and his friends, and, moreover, has been largely forgotten. And yet these waves of memories are what compel Herman to remain with his friends. Against all odds, they resist the force of progress in favor of their history in the valley. Soviet-era buses are the golden chariots that carry Herman deeper into his past. In one episode, he boards a bus crammed with his old soccer teammates, bound for a game deep in the cornfields. When he later learns that most of the players have long since died in fights or of alcoholism, the reader is left to question which parts of Herman’s Odyssey are real and which a dream.

The foggy ghost world that is Eastern Ukraine exists in its own dimension. And Voroshilovgrad, a city that Herman confesses to never having visited, not even before it became Luhansk, is itself a fantasy — the lost place of characters’ longing. By the end of the novel, Olga has discovered her misplaced postcards of Voroshilovgrad:

A whole stack of them. […] It’s funny, there’s no such city as Voroshilovgrad anymore, and the boy from Dresden doesn’t write me anymore, and it’s like none of that even happened, or it wasn’t even part of my life. […] Maybe these pictures are my past. Something they took away from me and forced me to forget. But I haven’t forgotten, because those really are a part of me.

With Voroshilovgrad, Zhadan has created an authentic poetics of post–Soviet rural devastation. His ragged, sympathetic characters aren’t the newly rich post–Soviets of Moscow, the urban oligarchs Peter Pomerantsev has described, who “sing hymns to Russian religious conservatism — and keep their money and families in London.” They are individuals struggling to come to terms with their place in history and with the history of their place. Zhadan’s literary Ukrainian is similarly a combination of colloquial language and soliloquy. To their enormous credit, Reilly Costigan-Humes and Isaac Wheeler have come up with vernacular phrases strange enough to remind us that the novel is a translation, placing the book firmly in its Eastern Ukrainian context, yet familiar enough for the English language reader to identify with characters negotiating their place in the world in the 21st century.

Zhadan’s rough, masculine writing has been compared to Charles Bukowski’s. However, his work also fits in with the best of borderlands prose. Gloria E. Anzaldúa’s poetic meditation on Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza comes to mind, as does Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children. The Russian-Ukrainian border is an oil border; the Donbass has long been mired in disputes over gas lines. As Herman traces the borderlands, occasionally traversing into Russia, he is constantly butting up against the gangsters and smugglers who deal in oil. The theme is present across Zhadan’s oeuvre. In his poem, “Lukoil,” he describes a corpse, laid out for his funeral beside “his newest nokia,”

Oh, death is a territory where

our credit won’t reach.

Death is the territory of oil,

let it cleanse his sins.

(Trans. Virlana Tkacz and Wanda Phipps)

Now that the territory has been torn apart by war, Zhadan’s 2010 novel seems eerily prophetic. Voroshilovgrad makes clear how unsurprising the ensuing confrontation in the Donbass should be. This hasn’t escaped Zhadan’s Ukrainian readers, and director Yaroslav Lodygin is currently making it into a film with music by Sergei Prokofiev. The gangs, violence, boredom, and economic fragility is a time bomb waiting to go off. “I knew that something was going to happen,” Olga says to Herman after a showdown at the end of the novel. “I could just feel it. But there was nothing I could do.”

But the novel also makes clear how tragic the Russian-Ukrainian war is for those in the East. As Mayhill Fowler has noticed, by writing Ukrainian fiction about the East, Zhadan differentiates himself from well-known Western Ukrainian language writers like Oksana Zabuzhko, Yurii Andrukhovych, and Taras Prokhasko. “Ukraine is not a non-Soviet place for Zhadan, but a place struggling with a Soviet past.” Notwithstanding his role in the Euromaidan demonstrations, he is enormously popular in Russia, where his books are translated quickly and sell well. He was nominated twice for the Russian GQ’s Man of the Year. Zhadan’s appreciation of a shared post–Soviet experience helps to explain just how much is at stake in Herman’s journey into the past. It is a journey to reclaim that part of himself still struggling with the Soviet past, struggling to sort out the complicated relationships that had reached a beautiful, messy impasse sometime around 1990, when Herman’s team briefly celebrated winning a soccer match, Voroshilovgrad was replaced by Luhansk, and Ukraine declared its sovereignty. In 2014, after his brow had been split open and his jaw broken, Zhadan nonetheless told Radio Free Europe, “We must now look for areas of mutual understanding, we must start talking to each other again.”

¤

LARB Contributor

Amelia Glaser is associate professor of Russian and Comparative Literature at University of California, San Diego.

LARB Staff Recommendations

“The Tribe” and the Language of Cinema

The more we meet "The Tribe" on its own terms, the more we are reminded that Sergey's tribe lacks something.

Eastern Europe: Return to Normality?

The supreme irony: just as Central Europe achieves "normal" status, joining the EU, the EU threatens to split apart.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!