Throbbing Between World and Nothing: On Robert Glück’s “About Ed”

Rose Higham-Stainton reviews Robert Glück’s “About Ed.”

By Rose Higham-StaintonDecember 13, 2023

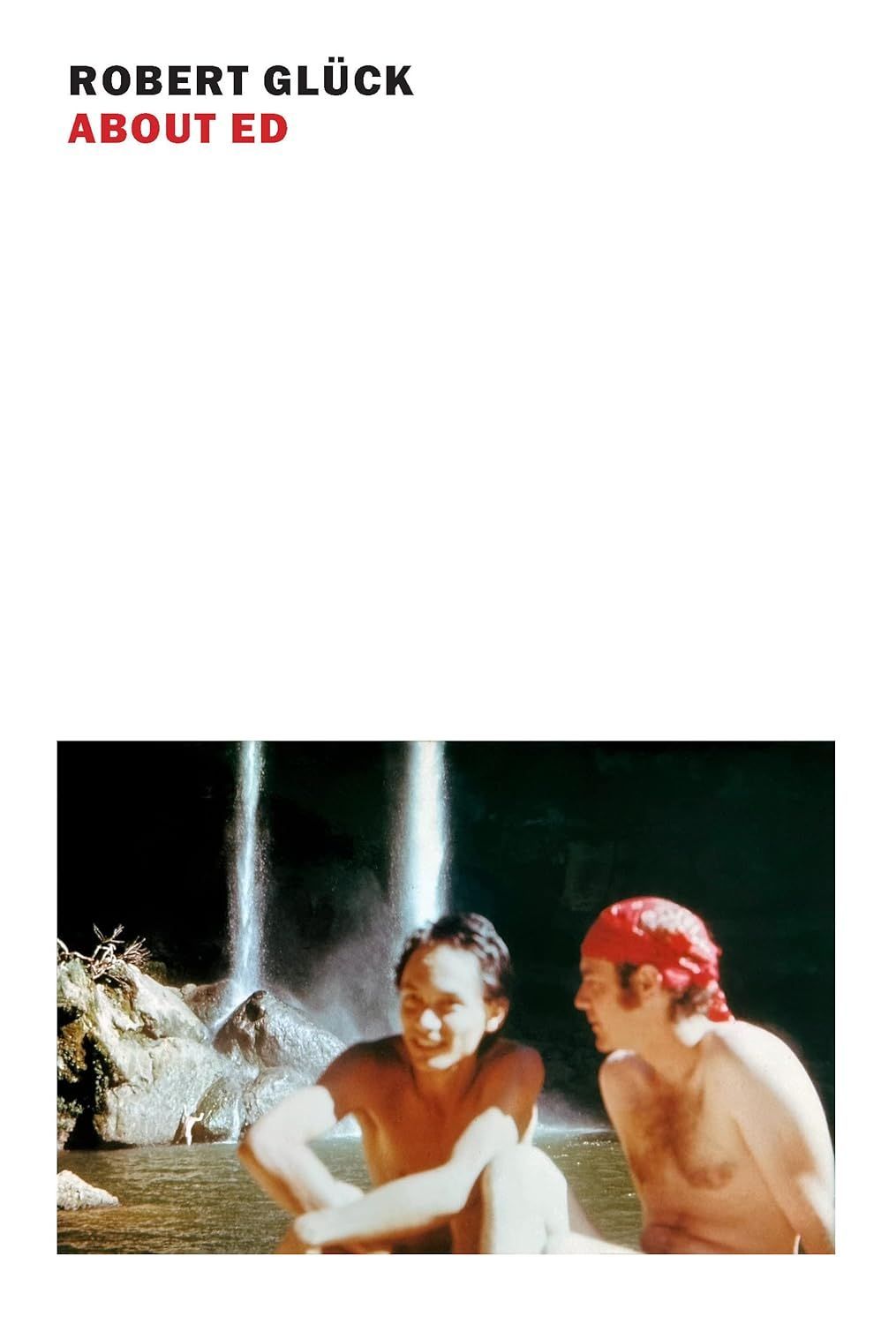

About Ed by Robert Glück. New York Review Books. 280 pages.

IN ROBERT GLÜCK’S new novel About Ed, the author grapples with what is unlikely and fantastic about death. “Nothing nothing nothing,” he writes, “is more unlikely—not hell or rising from the dead or bardo states or the Isles of the Blessed—nothing is more fantastic than for someone you love to stop, just stop, and be lowered into a hole and covered with concrete and actual dirt.” By “fantastic,” Glück means the inconceivable distance between death and life, while “nothing” operates as a refrain for the book, but also a kind of premonition—a premonition of the death of Glück’s longtime friend and sometime lover Ed Aulerich-Sugai. The novel chronicles Glück’s struggle to come to terms with the experience of not having—but also perhaps not wanting—love, company, or resolution.

About Ed recounts, in nonlinear fashion, the relationship between the author and founder of the New Narrative movement, Robert Glück, and his sometime lover, Ed, in and around San Francisco from the 1970s up until Ed’s death in 1994, and its aftermath. It is also Glück’s version of—or response to—the AIDS memoir, and Ed was not just compliant but complicit in it, providing notes for the day he was diagnosed HIV positive and permission to mine his dream diaries. These documents are interwoven with recorded conversations and Glück’s own memories.

Bob met Ed at a streetcar stop in San Francisco in August 1970. Ed had inherited his Japanese mother’s dark thick hair, which fell far below his shoulders; he wore a blue peacoat, we are told, that obscured his thin body. They were both new to San Francisco and arriving at their sexuality: “Learning about each other meant learning about gay sex.” For the next 10 years, it would be Bob and Ed—promiscuous, enraged, devoted, and fallible, in themselves and in the relationship. Their intimacy was the result of two lonely people coming together: “Ed and I were made for each other—loneliness so poor it couldn’t afford words,” writes Glück. Ed found fulfillment and satiation by having sex in parks and clubs with strangers and friends, while pursuing a painting career. Bob assuaged his hunger with poetry—“I beat back my isolation through writing,” he says—and by cooking, cleaning, and supporting his lover’s career.

Central to the narrative is the gay community—and the counterculture that sprung up around it—in San Francisco during the 1970s. “Ed lived the era, was committed to it; I only halfway,” writes Glück of his reticence about promiscuity, we might assume because of AIDS, which was at that point ferociously turning bodies against themselves. “I cared less that Ed fucked so many,” he laments, “than that I couldn’t manage to.”

The narrative stops and starts and digresses like relationships do. The book is split into three sections and numerous chapters; the first section, “Everyman,” builds a retinue of characters and encounters—morts and petites morts—in Bob and Ed’s lives. At the tender heart of the book, both structurally and conceptually at its middle, is the partnership of Ed and Bob—their isolation, their loneliness, and their loving. Glück arrives at the beginning of his and Ed’s relationship a third of the way through, before moving back to detail their individual childhoods and forward to their separation some 10 years later, then back again. So, although the book is about Ed, it is also about Bob, refusing the futile distinction between biography and autobiography. It is hard to write about a person without leaving a residue, Glück reminds us, and to pay heed to a life, there must be a certain kind of intimacy—some line that is crossed—between the teller and the one being told. Glück turns this into a narrative third dimension, the way that writing this book becomes for him a third separation (if we take into account their initial breakup and Ed’s death in 1994), but also perhaps a reconciliation, if not with Ed then with himself.

Along with Bruce Boone, Glück founded the New Narrative movement, which encouraged an unapologetic muchness and an unwieldy poetic prose that rejected the formalism of the group’s contemporaries, the Language poets, all while wearing its heart firmly on its sleeve. Six or seven years before the movement emerged, Glück and Ed and a number of others had formed a group known as “Parachute Salon”—a “literary school that underwrote its psychedelic surrealism with strong emotion,” holding forth at Intersection (for the Arts) and other venues in and around San Francisco, paving the way for New Narrative. Like Glück’s previous novels, Margery Kempe (1994) and Jack the Modernist (1985), and in the mode of New Narrative, About Ed seeks authenticity not in neat biographical details or facts, or in any kind of thesis, but in the scraps and residues of a life. The story builds a kind of density of feeling—a body even—via entries from Ed’s dream diaries, as his AIDS-related dementia sets in.

The novel’s form is not confined to the shape of the page or its syntax; Glück augments a particular kind of shape to his writing—has a spatial dimension that is fleshy and dense, brittle and easily bruised, but one that can also be emptied or hollowed right out. “My life was an emptiness I couldn’t fill,” Glück says in the wake of Ed’s death—but wasn’t it always? This phrase returns a page later like a stark refrain, emerging as the central focus of this book—one corroborated by Glück’s other great passion, pottery. For some two decades, Glück has made pots—votives and death rattles waiting to be filled with grief and memory. The same might be said of his writing—in About Ed, he excavates and purges himself, in order to make room for the words to enter, for Ed to enter. “I was bursting with Ed,” he writes towards the end of the book.

After Ed has died, Bob helps organize his possessions—“by the end there it was: Ed’s life, with its shape and no other.” Alive, Ed is all form and no content, no substance; insatiable and hungry, he constantly seeks ways to fill up—in plentiful orgasms, in the verdancy of his garden, where “[a] hundred tulip bulbs doze in the soil.” Dead, Ed is all content and no form—a series of physical possessions. Because, despite his vigor, his alternative remedies, his bottles and potions, death was an emptiness Ed couldn’t fill.

For Glück, that emptiness is life itself. “If my experience had not been so empty, I’d need to empty it myself,” he writes, delivering this assertion not with maudlin self-pity but with a kind of relief at being the custodian of emptiness. Over the course of the story, Glück reconciles with that emptiness, returning to the word “empty” over and over again, but he also makes a case for it—for turning negative space into an opportunity. Glück rarely appears on the page but we feel him, like the shape of a bottle or an empty shell.

This hollowing out also makes room for material stuff, the stuff of the body but also the stuff that bodies surround themselves with. Glück devotes a long passage to the great cedar bed that he and Ed built together, some three feet off the ground, and that Glück still sleeps in—a bed that “supported so many moments of fullness and emptiness that started with Ed and continue in the present.” But there are more ephemeral things too, like the lemon Bundt cake—a recipe from Glück’s mother—and the exotic microwave food he inherits from his neighbor Mac after his death; there are also the 18th-century scallop-edged Imari dishes, rendered in Glück’s attentive prose. Material things open and enliven the space between the living and the dead—what Glück calls a “throbbing between world and nothingness”—and holds them to account: who made them, whom they have belonged to.

“With a cock in me my darkness is vaulted with pleasure and the blurred lights of ornate chandeliers,” writes Glück, comparing his sexual experiences with grand interiors. “Eyes wide open,” he continues, “empty.” Despite or because of Glück’s (self-confessed) tendency to love too much—a reference to the anthology Writers Who Love Too Much: New Narrative Writing 1977–1997 (2017), edited by Dodie Bellamy and Kevin Killian—he longs to be emptied, purged or jacked off. The longing becomes its own poetry, from emptiness as invitation and space to be filled (an open palm or orifice) to something more anarchic, having to do with dissolution and breakdown of structures. Of his own generation, Glück writes, “We accepted the infinite—the expanding universe […] The opposite of physics, each new version was more disunited.” Glück co-opts physics, building a universe that expands narratives and conflates grief with lust. He also brings the reader into the story, addressing us directly as “Reader” and holding us to account; then sometimes Georges Bataille or Michel Foucault enters from stage right for a cameo part.

Glück is as explicit about the writing process as he is about the body and loving. Writing Ed and writing About Ed—doing it and failing at it—become a central preoccupation. “For decades I moved fragments from one journal page to another,” writes Glück of 24 years of notes about Ed, “pieces of Ed’s life and my own experience, decaying haystacks in the computer, events without dialogue, codes breaking down and formats degrading from one platform to the next, scraps spindling on my desk and in my head, gestures that yellow and fall from the branch.”

After the novel has “fallen apart,” Glück turns to Ed’s dream diaries—“Are they a condensed version of Ed? Shorthand?” he ruminates. The final section of the book is titled “Inside,” and for 50-odd pages we are inside Ed and his mind as he describes ponds and oceans, forests and animate life, bodies and orgasms, lovers and childhood trauma, in sometimes unnerving hallucinatory fragments that work against time. Each new fragment opens with the relentless refrain “Before that,” which is positioned at the tail end of the line on the page and spills haplessly into the next. At first, Ed’s lover Daniel is there, in the dreams, then Skip—the man he left Bob for—enters, and then Bob returns to augment his own death, and then later returns again as “Father/Bob,” referring to his role as carer during and long after their relationship expired. Arriving at the end of the book, “Inside” could be read as a kind of undoing of the novel, or perhaps Bob showing Ed his love and devotion by giving Ed the last, raw, inflammatory word, in a present moment from which he has been painfully and cruelly extracted, and amid a world that refused to acknowledge him as an artist and a victim of AIDS both when he was living and now that he is dead.

Glück’s part in the book ends with another sexual encounter, this time between him and a young preppy-ish man called Zack whom he meets on Craigslist and who, despite having a girlfriend, wants to experience gay sex and has chosen Glück as his older, wiser master. After the event, Glück writes, “[s]ex made me teary, as though mixing grief into my excitement made it honest,” and I am reminded of the form of the vessel, Glück throwing clay on a potter’s wheel and coiling it into pots, mixing in a little water with his fingertips as he formulates a space in which to reconcile with his grief—a grief that is not just about Ed but about his own life as it approaches death as well. “I started this book two decades ago, so now it has turned into a ritual to prepare for death, and an obsession to put between death and myself,” writes Glück, describing not only his book but also the empty space that it contains.

LARB Contributor

Rose Higham-Stainton writes about visual art, literature, and material cultures. Her work is held in the Women’s Art Library at Goldsmiths College and has been published by The White Review, Art Monthly, Apollo, Texte zur Kunst, Artforum, Worms Magazine, and Bricks from the Kiln. Her first book, Limn the Distance, is out now with the interdisciplinary publisher JOAN.

LARB Staff Recommendations

When One of Us Dies: On Mathieu Lindon’s “Hervelino”

Edmée Lepercq reviews Mathieu Lindon’s memoir “Hervelino,” translated by Jeffrey Zuckerman.

A Life Touched by Profound Illness: A Conversation with Meghan O’Rourke

Meghan O’Rourke discusses her new book, “The Invisible Kingdom: Reimagining Chronic Illness.”

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!