They Wanted to Bury Us: A Conversation with Andalusia Knoll Soloff

Andalusia Knoll Soloff reflects on the sixth anniversary of the Ayotzinapa forced disappearances.

By Annie RosenthalNovember 24, 2020

ON SEPTEMBER 28, 2014, multimedia journalist Andalusia Knoll Soloff was enjoying a quiet afternoon at home in Mexico City when she received a text: there was trouble in the state of Guerrero. Two nights before, students from the rural teachers’ college in Ayotzinapa had commandeered passenger buses to head to a protest commemorating a 1968 government massacre in the capital. In the small city of Iguala, police had surrounded the buses and opened fire, injuring dozens of people and killing six. Forty-three of the students were abducted — and disappeared.

Over the years that followed, Soloff, a New Yorker by birth who has lived in Mexico since 2013, reported extensively on Ayotzinapa, sending dispatches abroad for Al Jazeera, VICE News, NBC, and other outlets as the case consumed the country. The Mexican government’s “historical truth” asserted that corrupt police officers had handed the students off to members of a local gang, who incinerated them. Independent investigations discredited that story, suggesting instead that the attack involved high-level cooperation between the police and military. Soloff spent three months living on and off in the Ayotzinapa school with the families of the disappeared, and many more months documenting the protests that have ignited Mexico with demands that the missing 43 be returned alive.

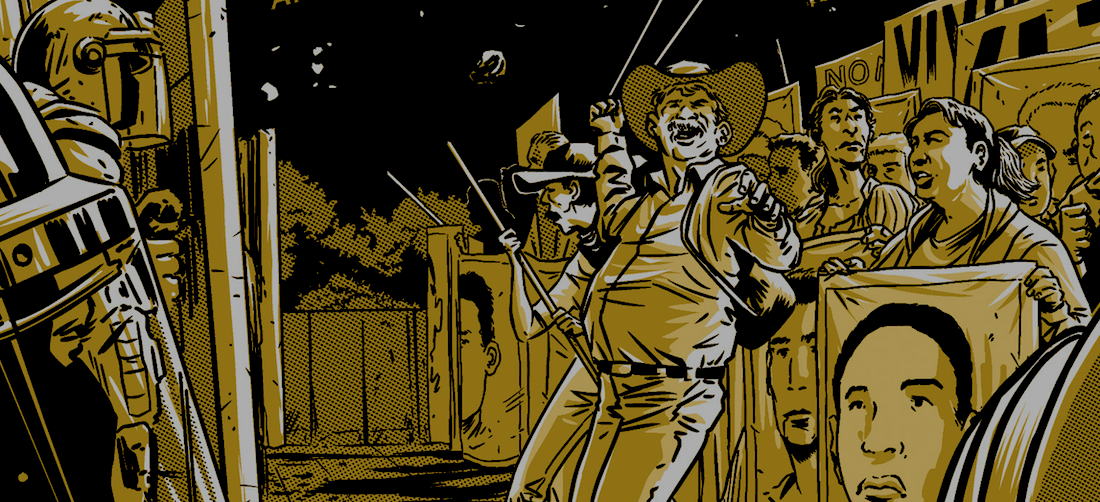

Still, Soloff — better known as “Andalalucha” — was unsatisfied with the emotional power of her short reports. So she settled on a new approach: a graphic novel. Vivos se los llevaron (Alive You Took Them), a five-year collaboration between Soloff and Mexican artists Marco Parra and Anahí H. Galaviz, follows the families of the 43 students, as well as survivors of the assault, through their first year in pursuit of justice. The book was published by Penguin Random House in Mexico last fall, and in the United States in March. (The first chapter is out now in English; a fully translated volume will likely be released this year.)

Six years after the attack in Iguala, forensic teams have identified the fragmentary remains of just two of the Ayotzinapa desaparecidos. The students are still among the ranks of more than 70,000 missing people in Mexico, most of whom have disappeared since 2006, when the drug war began. A few days after the sixth anniversary of the disappearances, I spoke with Andalusia over the phone about the potential of graphic journalism, the challenges of reporting on violence, new updates in the case, and what Ayotzinapa can teach US residents amid our own uprisings over police violence.

¤

ANNIE ROSENTHAL: This book is different from many others about Ayotzinapa in that it focuses largely on the families and their first year of activism, rather than just narrowing in on the facts of the attack itself. I’ve noticed that you tend to focus on activists and families in your other journalistic work too.

ANDALUSIA KNOLL SOLOFF: I often try to show that there’s dignity and resilience, because if you just focus on the victims of violence as victims and not also agents of change, it just makes the reader depressed. And I don’t think it actually helps instill social change, which is what I try to do with my work as a journalist.

I focused on the families partially because no one else was focusing on them. It was also part of spending so much time with them. I actually traveled on a caravan all across Guerrero with them where we went to the towns that they were from. Before Ayotzinapa, some of them didn’t speak Spanish; they spoke a native language. Many of the women were housewives and not very vocal. Maria de Jesus Tlatempa, who is one of the main characters of the book, was a housewife and also a street vendor. And little by little she became a spokesperson for the movement of the families. She traveled to New York, she traveled to Europe. I remember standing on this highway in Tixtla, Guerrero, after the families had just been attacked by the police, and her speaking so eloquently, asking, “Why is it that they attack us? Why do they care about these elections if all they do is just kidnap our children?” And that was when I was like, she’s my character.

Tell me how you came to the graphic novel format.

When I was a 19-year-old college dropout living in Pittsburgh and trying to figure out what I wanted to do in life, I used to spend hours and hours at the Pittsburgh public library, which had one of the first graphic novel collections in the country. I discovered Joe Sacco, Marjane Satrapi, Howard Cruse, who wrote Stuck Rubber Baby, Barefoot Gen by Keiji Nakazawa — I’m looking at my bookshelf right now. And Maus. I just loved them.

Mexico has a really long graphic tradition, but it does not have a journalistic or historical graphic novel tradition in the way that my graphic novel is. And so I kind of forgot about graphic novels and I didn’t read them for many years. Then I got a journalism scholarship at a university here and I was in a class on investigative journalism. During the break I was looking at Twitter and saw this tweet about a graphic novel on some conflict in Africa, I don’t remember what it said, and a lightbulb went off in my head. I was like, I know what I need to do.

What was it like to report for illustration?

If only I had reported for illustration! For nine of the 12 months of the book, I did not know I was doing the graphic novel. But in that time I essentially documented everything that happened, so the majority of the book is reported from my own archive of stories and videos and photos.

Once I decided on the characters, I did have to repeatedly call those characters, asking them for details of what had happened on this night: if the fiscal (prosecutor) that interviewed them had a mustache, if the room was big, if the room was small, how old he was. Many of these details are ones that seemed very absurd to the people I was interviewing. Now they see the book and they understand why I asked them.

Ideally, with a graphic novel, you write it and finish the script and then give it to an illustrator or you illustrate it yourself. But I had no idea how to write a graphic novel, and I was a full-time freelance journalist, working on Ayotzinapa and many other things that were happening in Mexico. The book became a really enormous collaborative effort. There were times when we were all staying at the studio at my house, working almost 24 hours and sending pages back and forth in taxis between the illustrator and the inker, then scanning them and sending them to Sinaloa, where someone was filling in the gray tones, and then to the state of Mexico, where someone was putting in the text.

Since 2000, more than a hundred journalists have been killed in Mexico, including at least five this year. You and Marco Parra have also collaborated on a short graphic novel called They Are Killing Us, in which you quote journalist John Gibler as saying, “In Mexico it is more dangerous to investigate a murder than commit one.” I’m curious about how you navigated protecting your own safety while reporting this story.

Journalists in Mexico often suffer attacks when they expose the relationship between organized crime and the government, and Ayotzinapa was exactly that, a collaboration between organized crime and the government. One example that was documented in the book: we went with three different cars of reporters to go investigate the garbage dump where the government had said that all the students had been killed and burned to death, and on our way back from that garbage dump, which was in a place with very little phone service, completely isolated, we were asking people if they had seen anything that night. Two big black SUVs rolled up right at that moment, harassing us about what we were doing there. They had no license plates and tinted windows and we could barely see their faces. So that was a very clear message, from whoever it was: We don’t want you to be investigating here. The only thing you can do at that point is get out of there.

Freelance journalists like myself also don’t have any media outlet backing us up when we are in these dangerous places. If we are attacked or detained or kidnapped, there’s often no one really paying attention. So that’s why I’ve gone on to found an organization called Frontline Freelance México, which is a combination between a press freedom organization, a somewhat informal trade union, and a mutual aid network for freelance journalists.

There’s also always a scale of advantage for reporters. I’ve lived in Mexico for years, and most of my colleagues are Mexican journalists. But I know that in my worst-case scenario I have a privilege that most Mexicans don’t have: I could get on a flight tomorrow and go to the United States. While the United States says it supports press freedom, journalists seeking asylum there have often been denied it and have had to return to work in the dangerous conditions that they had fled.

An added challenge to reporting on violence in Mexico seems to be how to cover it without normalizing or sensationalizing it.

Julio César Mondragón, who was one of the students who was murdered that night — his face was flayed. There was that picture that circulated all over the internet. What is the point of torturing a young man and stripping his face off? It’s to instill terror in the population. By sharing an image like that, you are repeating that terror. But also, you can’t deny that it’s a very brutal act that you do need to report on. For us it was important to show it, but we showed it in a much more discreet way, which you can do more easily with illustrations than you can do with photography or video.

There’s a whole genre of Mexican reporters who focus on the perspectives of the victims of violence. Many of them are members of Periodistas de a Pie (a network of investigative journalists) — Marcela Turati, Daniela Rea, Mónica González. I would say I follow in that line of journalism. You can never normalize when a mother is telling you that every single night she dreams that her son could come home, you know? I think it’s making sure that you don’t think, “Oh well, they live in a dangerous state and it’s a dangerous place so they were kidnapped and life goes on.” The victims themselves don’t normalize the violence, so as long as you are centering the victims’ voices, you will not normalize the violence.

It was eerie to read this book now, as people in the United States are taking to the streets to protest police violence here. There were so many clear parallels: the police crackdown on protesters, the outsize concern with property over human lives, the lack of government accountability. What do you think readers in the US can learn from the Ayotzinapa case in this particular moment?

Years back, there was a phrase that emerged here in Mexico: “Nos quisieron enterrar, pero no sabían que éramos semillas.” They wanted to bury us, but they didn’t know that we were seeds. I did notice that many people within the movement against police violence, largely within African American communities, were wearing shirts that had that phrase on it, because they also bear the same brunt of police violence and feel that their lives are not valued. One thing that both movements have done is put forth the families of the victims of police violence. And similarly, in both countries there’s a deeper critique, that it’s not just (a few) bad apples within the police.

I think that the strength of the Ayotzinapa families and the fact that the case is still being investigated six years later, whereas without their insistence the case would have been closed a long time ago — that strength and collective action can be an inspiration to people in the United States.

Just this past weekend, the Mexican government issued arrest warrants for dozens of members of the police and military whom they believe were involved in the disappearances. What do you think that will mean for the families of the missing 43 students?

Consistently, throughout the administration of AMLO [Andrés Manuel López Obrador], the families have felt a glimmer of hope that they are at least investigating the cases. Arrest warrants for soldiers has been a demand of the families for years. There’s a whole chapter detailing the army’s possible involvement and denial of medical services to the students on the night of September 26, 2014. So there is some hope now that what has been hidden for many years about the role of the army could reveal more information about what happened to the students on that night.

Finally, I’m curious about how your thoughts on your audience have changed over time — who you hope to reach and who the book has resonated with so far.

When I first started, I had thought that the book would be coming out first in the United States, that that’s where the audience for a graphic novel was. But then when we distributed the first chapter to the families, one of the mothers, Minerva Bello, said to me, “I never got past middle school and I can’t really read that well but I can understand your book.” That was when I was realized that there was a whole other audience of people who have had little access to formal education and don’t have very high levels of literacy — that the graphic novel also helps them understand the case.

Before the pandemic, we were able to travel to four different towns in Guerrero and do presentations. There was this amazing moment where I was in a town called Xochistlahuaca, which is an indigenous town, and it was their community radio anniversary. I presented the book and during the presentation it was being translated live in Amuzgo, the local language. All of a sudden, all these other people showed up to buy the book. And one of them said, “I heard that it’s a good book for teenagers to read, or young people, and I want to buy it for my son.”

When we presented the book at the Oaxaca Book Fair last year, I never thought I’d need to tell people what happened in Ayotzinapa, because it’s like this bloodstain on the history of Mexico and everyone knew the case. But I realized that many people in the audience had only heard the word Ayotzinapa and didn’t actually know what had happened.

When we started working on this, I never dreamed that it would take five years, but I did know that it was something important for the collective memory — a tool against forgetting.

¤

LARB Contributor

Annie Rosenthal is an independent journalist and writer. Currently a Yale Parker Huang Fellow and Overseas Press Club fellow focused on migration and the justice system, she's committed to telling stories about how communities and individuals reckon with and overcome violence. Follow her on Twitter at @AnnieRosenthal8.

LARB Staff Recommendations

High Art in a Low Place: On Don Winslow’s “The Border”

Jim Ruland visits “The Border” by Don Winslow.

American Idiots, American Killers, and the American Graphic Novel

Paul Morton reviews Jules Feiffer's latest graphic novel, "The Ghost Script."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!