These Family Legacies: A Conversation with Ruth Madievsky

Sasha Vasilyuk speaks with Los Angeles–based author Ruth Madievsky about her debut novel, “All-Night Pharmacy.”

By Sasha VasilyukAugust 7, 2023

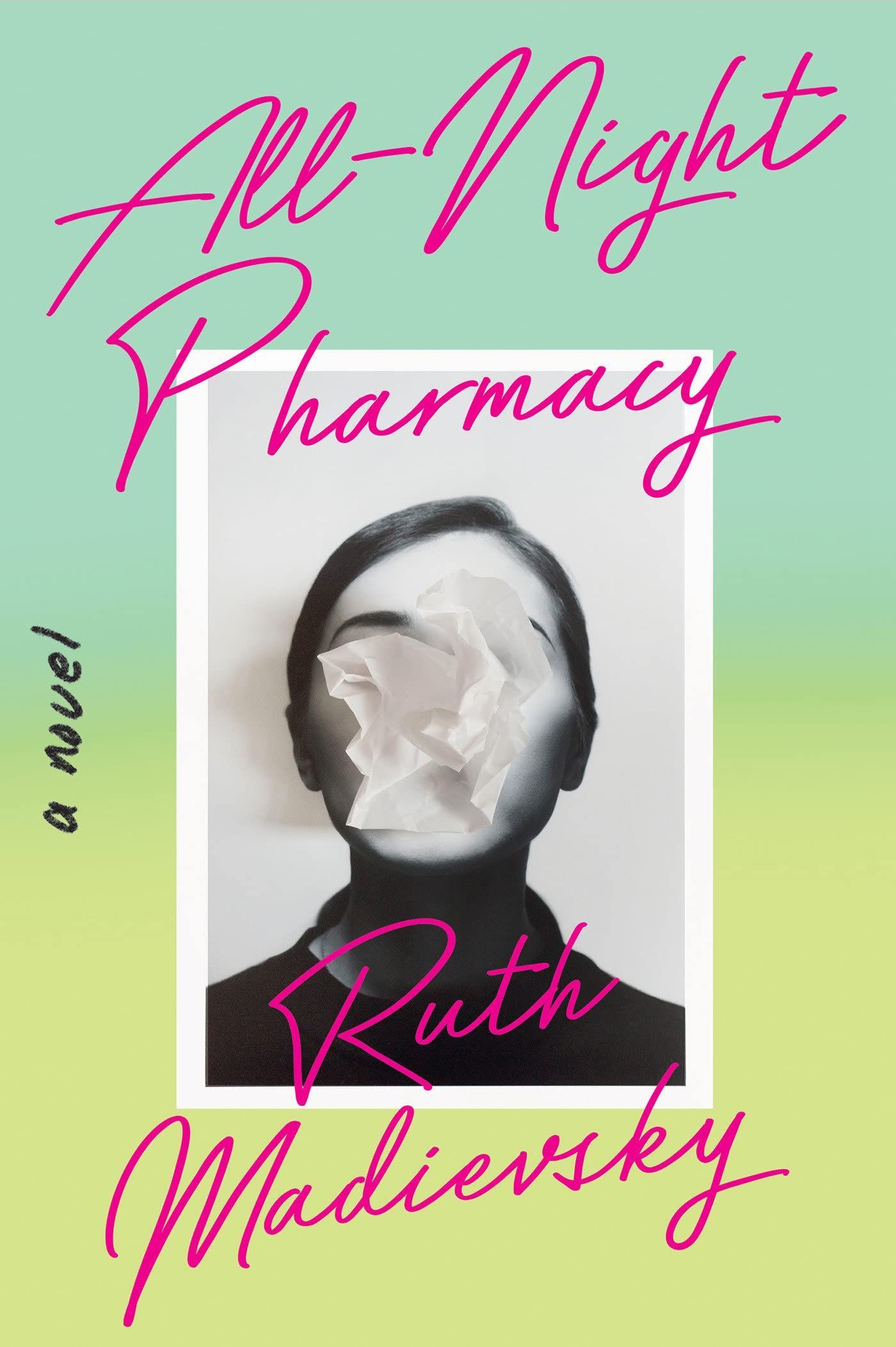

All-Night Pharmacy by Ruth Madievsky. Catapult. 304 pages.

I FIRST HEARD Ruth Madievsky read from her debut novel All-Night Pharmacy (2023) as part of a group reading of post-Soviet writers in Los Angeles, entitled Embattled Homeland. The passage she chose took place at a Jewish cemetery in Moldova, the country where Ruth was born and where she lived until her family immigrated to Los Angeles when she was a toddler. I remember the funny-sad affect of Ruth’s voice as an enigmatic character named Sasha told the narrator the story of a World War II–era cow named Nochka that blew up on a land mine.

I had previously interacted with Ruth online in the first weeks of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, when those of us from the former Soviet Union who now lived in the safety of the United States were suddenly reexamining our homeland, the new war and the old one (World War II), and our very languages and identities, which we had thought were immutable but which turned out not to be.

All-Night Pharmacy is not, on its surface, about any of those things. It is a quippy, rollicking novel of women behaving badly in a gritty Los Angeles, where a young unnamed narrator struggles to untangle herself from her toxic older sister, Debbie, until Debbie goes missing. I could almost say that All-Night Pharmacy is sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll, except that I’d need to replace rock ’n’ roll with a Soviet babushka who embodies the generational trauma underpinning the arc of the story.

Ruth, who works as a pharmacist and is the author of a poetry collection, Emergency Brake (2016), spoke to me about the journey behind the novel and what’s it been like to see All-Night Pharmacy reach the USA Today bestseller list a week after publication.

¤

SASHA VASILYUK: What was the genesis of All-Night Pharmacy?

RUTH MADIEVSKY: It started out as a linked short story collection, where I would write a new short story twice a year when T. C. Boyle would come to the USC campus to meet with PhD students in the creative writing program. I was in the doctor of pharmacy program on a different campus altogether, but because I hung around the creative writing program’s events so often, they took pity on me and let me meet with him. And that was how I ended up with a handful of short stories about this unnamed narrator, a recent high school graduate who has a toxic older sister that has gone missing, and who is guided by this enigmatic Soviet Jewish refugee who claims to be a psychic, Sasha. And eventually it became clear that the stories needed something else to push them into a book worth reading.

That’s where your trip to Moldova came in, right? How did it help crystallize the novel for you?

I went to Russia and Moldova in 2018. That was my first time going back to Moldova since we emigrated, and that trip really inspired the second half of the book. It helped me tease out the thread about how historical traumas affect people who are several generations removed, which is something I didn’t even realize I was writing toward until after I took that trip. It helped the book become more than a story about sisterhood and addiction in Los Angeles but also a story about the immigrant experience, about generational trauma, and about the legacy of the Holocaust and Soviet terror.

I also felt like there are two parts to the book, even though it isn’t explicitly marked that way. Can you talk about the two halves and whether you like one more than the other?

I’ve always had a soft spot for the first half because those are the original stories that I’ve worked on since 2014. And I think that’s the more fun half, because that’s where you get all the drugs and a lot of sex, a lot of partying. We get the most weirdos packed under one roof in the first half and then the second half is the comedown, the repercussions, the recovery. I think that the second half brings it home more because that’s where we really tease out the generational trauma thread, where we see the narrator harness some agency rather than just be someone that things happen to.

The grandmother character centers the generational trauma thread. Grandmothers are a favorite topic for a lot of post-Soviet émigré writers. I’m thinking of Maria Kuznetsova, Katya Apekina, Masha Gessen. Why did you choose to make the grandma character whose modus operandi is to “dump all this horror on you, and then act affronted when it fucks you up”?

I mean, I also think she’s pretty funny. She is definitely very tough-love, but she also has this Soviet Jewish orientation toward life in terms of gallows humor. She doesn’t understand why her daughter and granddaughters are so messed up when they haven’t experienced a quarter of the trauma that she has. She has that kind of toughness that we see in some immigrants, where they have all these strong convictions about how to live and everything else feels indulgent, like therapy or being in touch with your feelings. I’m sure the narrator imagines that, for her grandma, queerness is an indulgence. So, I was interested in that generational divide.

In the past year and a half of the war in Ukraine, I’ve thought a lot about the pathological silence of the older Soviet generations. But in All-Night Pharmacy, there is a lot of dumping of trauma and also guilt-tripping. I haven’t personally experienced that. What I experienced was very much the opposite—everyone trying to spare you their trauma.

Yeah, it’s interesting. I’ve had both versions in my family. My late grandma, my mom’s mom, was in the “spare you” camp. When I was younger, she told me that her dad had died of a heart attack, and he’s the one who was killed by the KGB as an enemy of the state. She fully lied to me about it because I think she thought it would be too hard for me to know. My other grandma has gotten very chatty in recent years. She will tell me all kinds of family secrets. Now that she’s in her mid-eighties, I think she wants someone to hear the stories.

I was also thinking about a conversation I had with a friend whose grandparents were Holocaust survivors, who never spoke about their experience with their kids or grandkids. And so, there was this huge, unspeakable presence in their home at all times. I was interested in the different versions of how these family legacies make their way into future generations, with the thought being that they always do in one way or another.

And now we have our own trauma, with the war in Ukraine. What was it like to work on this book during the war? Has it impacted your understanding of that region, your own identity, or what role your book plays in the canon of Eastern European literature?

Like a lot of us from the region, I was thinking much more about my ethnic identity than I ever had before. About how I and a lot of my fellow immigrants who speak Russian always identified ourselves as “Russian” just because that was the language we spoke. It was kind of an easy shorthand. Only after the war started, it hit me: why do I say that? My family is from Moldova and Ukraine, but we’re not Moldovan or Ukrainian, because we’re Jewish. Now, what is the right term to call myself? Is it post-Soviet Jewish American? That’s kind of where I landed, even though it’s a mouthful. I was thinking about a lot of this stuff while I was writing the book and trying to be intentional about using the word “Soviet” or “post-Soviet” rather than “Russian” for anyone who spoke Russian.

It also felt more important than ever to capture how grim and abandoned the Jewish cemetery in Moldova was. And I wanted to capture some of the beauty of the country, the wildflowers and the hospitality of the people and how good the food is, even though Moldova has been one of the poorest countries in Europe. Thinking about the war and how Putin seems to be actively trying to destabilize the region, it felt more important than ever to try to do the country justice.

All-Night Pharmacy definitely puts Moldova on the map with the tremendous response it has received. What’s been the most surprising thing about the reception of the book so far?

It’s been really heartening to see how many people are into the generational trauma thread and understand why it’s important to the book, because that was definitely the most contentious part of the book when it was on submission. There were some editors who felt like this was a book about sisterhood and addiction, and not about the slippery aftermath of generational trauma. From the reviews that have come out and the people I’ve interacted with who have read it, no one has brought that up as a weakness of the book, and I think people generally see it as a strength. It’s been nice because that was something I was worried people wouldn’t understand.

Why do you think it has resonated so much with folks?

I honestly don’t know. I think that there’s definitely a hunger right now for stories about women behaving badly. I mean, there has been in recent years, so that’s not something that’s just happened this season, but I think that’s a fun genre of literary fiction for a lot of people. And I think that there’s more interest maybe now than there was 15 years ago in coming-of-age stories that don’t center coming out, in immigrant stories that aren’t just about racism, or these “capital letter” topics, but are more nuanced. So, I think that all of that might be in my favor, but truly, I have no idea. I just hope that people are into the story and the writing.

¤

Ruth Madievsky is the author of a bestselling poetry collection, Emergency Brake (2016), and a novel, All-Night Pharmacy (2023), and she is a founding member of the Cheburashka Collective, a community of women and nonbinary writers from the former Soviet Union. Originally from Moldova, she lives in Los Angeles, where she works as an HIV and primary care pharmacist.

LARB Contributor

Sasha Vasilyuk is a journalist and the author of a debut novel, Your Presence Is Mandatory (Bloomsbury, 2024), which spans from World War II through the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Her nonfiction has been published in The New York Times, CNN, Harper’s Bazaar, Time, The Telegraph, Narrative, USA Today, the Los Angeles Times, and elsewhere. Sasha grew up between Ukraine and Russia before immigrating to the United States at the age of 13.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Good Evening, We Are from Ukraine: The Subversive Radicalism of a Viral Wartime Slogan

Maria Sonevytsky explores how a simple phrase became a slogan invoked by Ukrainian politicians, soldiers, intellectuals, and keyboard warriors.

Russia Has Committed War Crimes in Ukraine

Don Franzen interviews law expert Mark Ellis regarding recent atrocities committed in Ukraine and the subsequent international pursuit of justice.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!