“There Is No Hole in Heaven”: On Jerzy Ficowski’s “Everything I Don’t Know”

Piotr Florczyk reviews the poetry collection “Everything I Don’t Know” by the late Jerzy Ficowski and translated by Jennifer Grotzm and Piotr Sommer.

By Piotr FlorczykFebruary 23, 2022

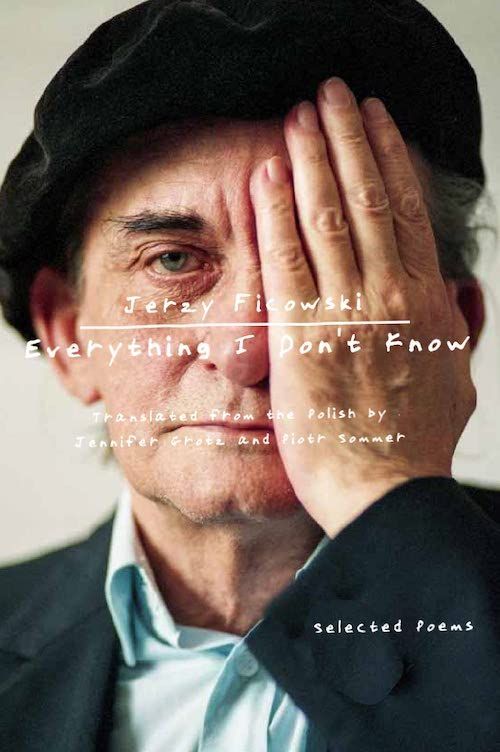

Everything I Don’t Know by Jerzy Ficowski. World Poetry Books. 192 pages.

WHEN IT COMES to the canonization of authors whose work spans multiple genres, it seems one can be a poet or writer or translator but not all of the above. To pigeonhole is, of course, the literary community’s prerogative, although the drive to stratify and classify its members can do more harm than good. Take, for instance, the case of the late Christopher Middleton — the British poet and translator excelled at both activities, but he was arguably more admired and better known as a translator. Ditto David Ferry, who will turn 98 in March.

To this list we must add Jerzy Ficowski (1924–2006), who is best known around the world — to those, that is, who’ve heard of him at all — as an expert on the Polish Roma community and, especially, as curator of Bruno Schulz’s work (prose, letters, drawings). Yet as Piotr Sommer argues in his afterword to the present volume, Ficowski was also “one of the most surprising omissions from the so-called canon of post-war Polish poets.” Indeed, as the author of 15 collections of poetry, Ficowski was not unknown, in the proper sense of the word, but he remained on the margins of the leading aesthetic and ideological currents during his lifetime, both in Poland and abroad.

Everything I Don’t Know culls poems from 11 volumes and presents them in chronological order. The first excerpt, from 1957’s My Sides of the World, introduces us to a poet who’s above all a keen observer of the people and things around him, attuned to the materiality of the world, with its apricots, door handles, and drawers: “Shelter for the sinful word, / o drawer, odyssey so vast, / made of oak, homeric!” In the following volume, Amulets and Definitions (1960), Ficowski doubles down on object studies, as seen in the wonderful sequence “From the Mythological Encyclopedia,” where a faucet, ashtray, cone, and candle are among the objects the poet scrutinizes and celebrates in his imaginative, even surreal peregrinations. What’s highly admirable is that Ficowski doesn’t end up privileging the human observer in the process, but rather simply embeds our subjectivity in the scene, as in “The Migration of the Hangers”:

Let’s watch from the domestic rubble,

overwhelmed and on our own,

how the hangers are suspended in air,

watch those further and further off —

we, the withered gestures,

extinct poses.

While Ficowski’s fascination with objects never abated, eventually he opened his poems up to include more disparate voices, including one markedly his own. Starting with The Bird Beyond the Bird (1968), we gain entry to poet’s existential preoccupations, to his world of memories, which are often downplayed, as well as to his friends and idols. This is when Bruno Schulz and the great Romani poet Papusza (1908–1987), whose real name was Bronisława Wajs, begin to appear in Ficowski’s work. During this time, he seemed to be searching for new points of reference, for a way to go above and beyond himself. The volume’s title poem is a study of a bird in flight, “unable / to outpace itself / by even a bird’s beak.” What appears like a defeat for the bird, however, quickly turns into a victory, where

The bird on a branch

sings in every direction

reaching for seven echoes

simultaneously

moves through contradictory distances

Ultimately, the bird escapes the narrow confines of its being — “Look / the bird victorious / throughout the forest // The bird beyond the bird” — and so does the human perceiving it.

The volumes Ficowski published in the late ’70s and early ’80s mark a major shift in his work. While the stylistic mode is still one of measured spareness, his thematic focus turns to the Holocaust and the plight of exiles and refugees. “I’ll tell you a story,” the poet writes, “before it emerges cleansed from us / that is from sand.” The allegory soon gives way to literal excavation:

I’ll tell it still warm

from the furnaces of auschwitz

I’ll tell it still frozen

from the snows of kolyma

a history of dirty hands

a history of hands severed

The stories Ficowski wishes to tell are not part of the official narrative; instead, they are the unheard ones, including those hidden so as not to stain the Poles’ own grand narrative about their struggle and sacrifice during World War II and in the following decades. The reliance on and presentation of facts aligns these poems with the docupoetry school so in vogue today, but the Ficowski channeled through Jennifer Grotz and Sommer’s sensitive translations remains fundamentally a lyric poet who wants to rescue the dead from oblivion and “to get there on time / even if it’s already over.” What does he find upon arrival?

There is silence in the meadows

of former battlefields

the bank of the bug river arranges

shells and bones

at times a wasp’s ricochet

shoots from the burdocks

someone was buried here

or somewhere else

and there is no hole in heaven

as there is on earth

Where does a poet go from there? This volume’s last three excerpts show that Ficowski forged ahead, documenting human folly with pain, empathy, and lyrical intelligence. His tone may have changed, turning quieter, more reserved, especially as the poet began to grow old, but not his drive to question and examine, to think aloud, inviting us, his readers, to take note, to keep looking in the proverbial mirror. This book includes many fine poems that speak to that difficult obligation. Some of them, like the poem that gives the collection its title, offer a momentary respite from scrutinizing self-reflection, because “even if holy days are no more / holy moments persist.” Yet it’s the volume’s final poem, called simply “We,” that deserves to be etched into our minds:

we animals superior

by our own nomination

we with our disappearing

tail of instincts

because without them it’s easier

to persist in our stubborn error

our opposition to nature

makes her itch

so she scratches herself and shudders

with a tsunami, for instance

then we die out a little

and those who remain

feel very sorry

That single comma in the penultimate stanza seems out of place, but we get the message, don’t we?

While I feel poems should always have the final say in a poetry review, let me close by returning to the point about reception and marginalization. In his afterword, Sommer attributes Ficowski’s sidelining to the fact that he “is a poet of local lore and myths, most inventively and most radically rooted in the phraseology of the Polish language, reaching into it with a particular Ficowskian imagination and discipline, fusing past speech with its current forms.”

This rootedness in the Polish language, which makes Ficowski’s idiolect so fascinating, seemed not to have endeared him to Czesław Miłosz, whose hugely influential anthology Postwar Polish Poetry (1965) cemented the canon of Polish poetry in English translation. And then there was his subject matter. “Wasn’t he full of sympathy for Jews and Gypsies,” Sommer asks rhetorically, suggesting reasons why one might be disqualified from ever joining the ranks of the chosen ones, “and for simple people, revealing his specifically ethnographic interests, and involvement, in things of limited importance?”

Fair enough — there’s no denying that many Polish readers were uninterested in such things. And sadly, the same can be said of Sommer, a highly accomplished and original poet who was born in 1948 and generationally belongs to the cohort represented by Adam Zagajewski (1945–2021). Although his is a regular visitor to these shores, he too has been sidelined by Americans’ continuing infatuation with the tribe of Polish poets whose preoccupations are decisively not quotidian but rather political and purely metaphysical.

The truth is that translating a poet like Ficowski or like Sommer is no cakewalk, and Miłosz’s decision to omit the former from his anthology can also be explained in purely practical terms. Indeed, Sommer and Jennifer Grotz are admirably forthcoming about having translated only those poems that “seemed translatable enough.” What they give is more than enough to establish Ficowski as a poet first and foremost. Anyone who so successfully translates what others deemed untranslatable deserves our full attention.

¤

LARB Contributor

Piotr Florczyk is a poet, essayist, and translator of several volumes of Polish poetry, including The Day He’s Gone: Poems 1990-2013 by Paweł Marcinkiewicz (Spuyten Duyvil, 2014), The World Shared: Poems by Dariusz Sośnicki (co-translated with Boris Dralyuk; BOA Editions, 2014), and Building the Barricade by Anna Świrszczyńska (Tavern Books, 2016). He is the author of East & West: Poems (Lost Horse Press, 2016), a collection of essays, Los Angeles Sketchbook (Spuyten Duyvil, 2015), and a chapbook, Barefoot (Eyewear, 2015). He is one of the founders of Calypso Editions, a cooperative press, and serves as Translation Editor for The Los Angeles Review. He lives in Santa Monica. www.piotrflorczyk.com.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Bruno Schulz: The Shadow of the Word

Philip Ó Ceallaigh goes in search of Bruno Schulz 76 years after his murder.

Against the Devil: The Tormented Life of Czesław Miłosz

Maria Rybakova reflects on the tormented life of Czesław Miłosz, as told in a new biography by Andrzej Franaszek.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!