The Way They Move

Jean Comandon's 1909 "Spirochaeta Pallida (Agent de la Syphilis)" brought together the history of science and technology, sex and entertainment.

By Sonia Shechet EpsteinDecember 25, 2019

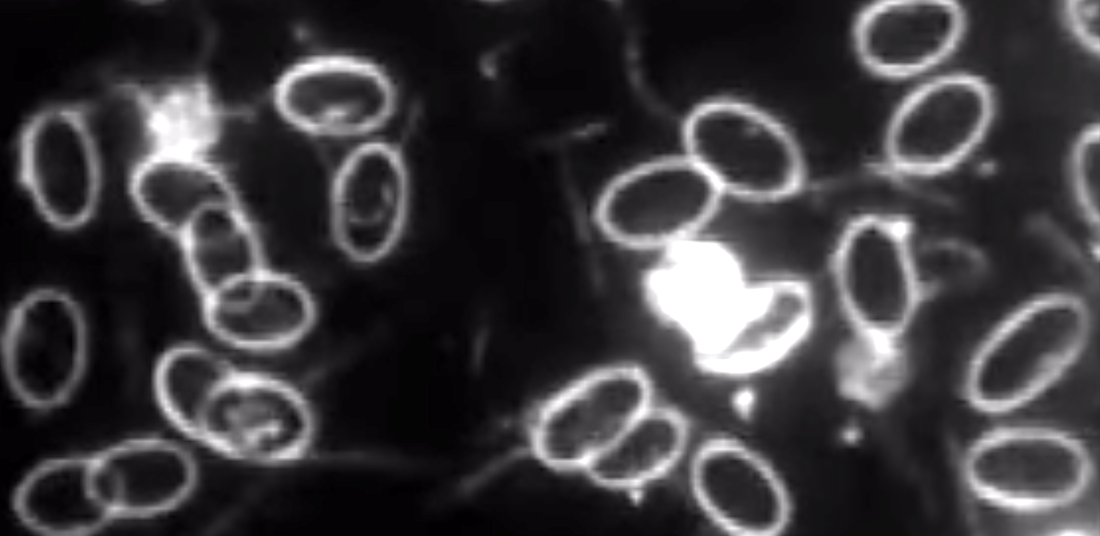

IN THE DARK, interstitial space between cellular bodies — lumpy masses that glow white — a parasite grooves. A wavy, fine line half a millimeter thick, the spirochete bacteria dances in wiggling spasms. Jean Comandon’s film Spirochaeta Pallida (Agent de la Syphilis) from 1909 feels infested. One after the other, bacteria twitch and burrow into skin cells. Intertitles state that the spirochete bacteria live in the cornea — the front surface of the eye. Invisible to the un-mechanized gaze, Spirochaeta Pallida shows them cluster there. Then, bacteria edge out of the frame to territories unexplored. Finally, a pair of spirochete entwines. They hump each other. Cut to black.

Just 13 years after Thomas Edison’s lightly erotic short — 1896’s The Kiss — microbiologist Jean Comandon directed Spirochaeta Pallida (Agent de la Syphilis), likely the first sex education film. Perhaps surprisingly, the entertainment industry took interest in Dr. Comandon’s work, enabling his innovative method of combining a microscope with a film camera to penetrate under the skin and reveal what could not be seen by the naked eye. Syphilis was then a mysterious yet ubiquitous venereal disease, and Comandon’s film titillated and educated, captivating audiences with content both sensational and vitally important. Spirochaeta Pallida (Agent de la Syphilis) brought together the history of science and technology, sex and entertainment. It was, in other words, an auspicious sign — and symptom — of film culture to come.

I.

[Syphilus] first felt strange pains, and sleepless passed the night. From him the malady received its name. The neighbouring shepherds catch’d the spreading Flame.

— Hieronymus Fracastorius (1483–1553), verse about the origins of syphilis

In 1909 at the Hôpital Saint-Louis in Paris, Jean Comandon perched at a laboratory bench, hunched over his ultra-microscope. True to its name, his microscope was more powerful than previous microscopes. Rather than directly illuminating a sample, the ultra-microscope provided an oblique illumination so that, in the way that dust floating is visible in a sunbeam, previously imperceptible specimens became evident. This “dark-field” illumination technique created a particularly cinematic aesthetic: microscopic life glowed white against a black background.

Comandon watched parasitic life — bacteria — sampled from human tissue. He knew that the person to whom this tissue belonged was infected with the disfiguring, painful, and ultimately lethal sexually transmitted disease so widespread that it was soon called “The Third Great Plague.”

Syphilis is easy to diagnose once it progresses past the incubation and primary stages; gross skin lesions, or pocks, grow near a patient’s mucous membranes — namely their mouth and genitals. At a late stage, the bridge of the nose can collapse. Comandon was set on finding a new diagnostic method for identifying syphilis in order to help end its scourge. If syphilis could be detected from a tissue sample, doctors would not have to wait until the patient presents with the obvious lesions months after they have been infected and have likely transmitted the disease to others.

The species of spiral-shaped bacteria, spirochete, which cause syphilis, was identified in 1905. These disease agents undulate in a way that allows them to move quickly and efficiently throughout the body and into the central nervous system. (The same species is responsible for Lyme disease.) It doesn’t take many spirochete bacteria to infect a person with syphilis. Someone with only about 50 Treponema pallidum, the subspecies of spirochete that causes syphilis, has a 50 percent chance of contracting the disease. Through open lesions on the mouth, genitals, anus, or through a mother’s placenta or a father’s sperm, spirochete can invade new hosts. In 1909, there was no cure.

Syphilis is sometimes referred to as the “great imitator” because its early symptoms — fever, joint aches — are common to other illnesses. But Comandon was interested in its causative bacteria’s movements: crinkled, thin, white lines swim in a zigzagging path. In sample after sample, he saw spirochetes move with this same peculiarity. They sway as they move — a unique characteristic that the ultra-microscope dramatically illuminated. This was a revolutionary discovery. The ability to identify spirochetes from their movement allowed for a rapid and certain diagnosis of syphilis from a tissue sample, even before early “imitator” symptoms emerged.

The scientific community and beyond began to take note of Comandon’s observations. Charles Pathé, a friend of Comandon’s mentor Paul Gastou, and half of the sibling duo that ran the major film production and distribution company Pathé Frères, proposed to Comandon that he move his research to their film studio in Vincennes, a suburb of Paris. There, Comandon could make use of another recently invented tool to create mechanically reproducible images: the cinematograph.

II.

It is a filthie disease, because it maketh women to be esteemed unchast and irreligious […] There is a twofold kinde of causes […] The first is the only influence or corruption of the aire, from whence we must charitably thinke, that it infected those which were religious. The second is conversation, as by kissing and sucking, as appeareth in children, or by carnal copulation.

— Juan Almenor, 1502

At Pathé’s studio in Vincennes, Jean Comandon began to build a device for making films that represented the microbiologist’s viewpoint. While Pathé’s campus included facilities to manufacture film equipment, build sets, shoot films (predominantly single-reel shorts), develop negatives, hand-color frames, and copy film reels for distribution, Comandon essentially needed a workbench for his subject matter. Recognizing the uniqueness of his work, Pathé documented Comandon’s device and prepared a patent application. On October 22, 1909, the company submitted an application for a micro-cinematographic camera.

Consisting of 25 component parts, the invention combined the camera and microscope. A light source, focusing lenses, and gears made it possible to move the camera to follow motion within the microscopic frame. In order to keep the living biological sample from dying as a result of light’s hot rays, the device had shutters and a cooling system. The image recorded on 35mm nitrocellulose (the likely industry standard of the time). The entire production suite was just a few feet long.

Comandon was 32 years old and finishing his doctorate when Spirochaeta Pallida (Agent de la Syphilis) was released in the fall of 1909. The three-minute-and-27-second film is about 200 feet long. It was first presented to a crowded room at the French Academy of Sciences by Academy member Albert Dastre, chair of physiology at the Sorbonne. “The consequences of Comandon’s discovery are incalculable,” Dastre began his introduction. “All the activities of microbes […] can now be studied with a precision hitherto inconceivable. Physiological questions of the greatest importance, impossible of elucidation in the past, can probably be solved by this new method.”

Audiences would have only ever read about spirochete bacteria, if they had heard of them at all. Projected, these bacteria appeared the size of a scientist’s head — 20,000 times enlarged. Using the film camera, Comandon had found a way to manipulate dimensions of the human world that are generally taken for granted — time and scale — not to mention the integrity of the human form.

Despite being about a pestilent venereal disease, Spirochaeta Pallida made headlines in Catholic France and around the world. “Microbes Caught in Action,” a special cable to The New York Times reported from Paris after the screening. The film caused “more open wonderment than is usually expressed by that body of cool-blooded savants [at the French Academy of Sciences],” the subsequent Times article claimed. “At last the microbe has been traced to its lair and photographed,” Pittsburgh’s New Castle News published on March 17, 1910. Vogue, in December 1909, even described Comandon’s film as hopeful news for anti-vivisectionists: “[I]nstead of the instructor in medical colleges sacrificing fresh animals for every class, the one experiment in its minutest details can be caught by a motion picture film and do duty for many hundreds of classes.”

Spirochaeta Pallida was hailed as a new aid to medical research. With the ability to slow down, pause, and replay scenes, film was recognized as a mechanism for making technical observations of living, moving microorganisms.

III.

A night with Venus and a lifetime with mercury

— aphorism

The standard treatment for syphilis at the turn of the 20th century was a three-year course of poison. Patients were prescribed nonlethal doses of arsenic and mercury, which had numerous debilitating side effects including tooth loss and kidney failure. At the time that World War I broke out in 1914, syphilis was spreading wildly. There was no vaccine.

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) were the second most common cause of absence from duty and disability during World War I, responsible for a reported seven million absent days and the discharge of over 10,000 men. By 1916, the French secretary of war declared syphilis a “national public danger.” Soldiers needed to be fit to fight. Desperate governments formed propaganda institutions to target soldiers’ sexual behavior in the hope of mitigating transmission of the disease.

The United States entered the war in 1917 with a vested interest in addressing the spread of syphilis. As US soldiers deployed to France, the New York–based Rockefeller Foundation formed a French Mission, commissioning films from Pathé to educate both soldiers and the public about how STIs were transmitted and best practices if infected. But in a Catholic country where men were supposedly waiting to have sex until marriage (meanwhile prostitution was widespread practice), a sanctioned film would not address extramarital sex directly, thus seemingly condoning promiscuity. Accordingly, Comandon’s next Pathé-produced syphilis film, On Doit Le Dire [It Must Be Said], was intended to educate viewers about what to do once infected. The film refers only in passing to the disease’s transmission.

On Doit Le Dire is a short, narrative propaganda film — a six-minute morality tale. A story about people and their actions, the film could not be shot solely through a microscope, as Spirochaeta Pallida had been. While a live-action shoot requires actors, director, makeup, lighting, and a location, animation is essentially a one-person job. So, Pathé paired Comandon with one of the leading animators of the time: Marius Rossillon, alias O’Galop — none other than the inventor of the iconic tire company mascot the Michelin Man.

On Doit Le Dire, which tells the story of two soldiers who take opposite approaches to life and love after they are diagnosed with syphilis, was shown to Allied soldiers in 1918. It begins with a hand-drawn, bespectacled gentleman sporting prominent sideburns who stands behind a podium. His mouth moves silently up and down. Via intertitles, he says that some people call syphilis “shameful,” but it is vital to discuss because one in five people in big cities are infected. The text goes on to obliquely state that the only shameful part of the disease is the immorality that causes it.

Mathieu, drawn as a lanky soldier with very tall boots, meets an appealing woman on Rue de la Santé [Health Street] and quickly ascends with her to a hotel room. The pleasures of love are fleeting, audiences are prompted with musical notations to sing. Later that night, after Mathieu has departed, another soldier named Mattéo sees the hourglass silhouette of the same woman in the hotel window. She sees him, and the next moment they are kissing. Four weeks later, the two men are feeling symptomatic. They spot a flyer for Le Professeur Charlatanos, who has proven that he can cure syphilis using herbs, without mercury. But Mathieu knows a charlatan when he sees one. He goes to see a “real” doctor.

In the doctor’s office, Mathieu drops his pants and with a quick nod, the doctor diagnoses him with syphilis. The dependable laboratory is then able to confirm the diagnosis; a familiar view of spirochete bacteria wiggling, reprised from Comandon’s 1909 film, is intercut.

Poor Mathieu is indeed syphilitic and contagious. He must follow the doctor’s prescription and if his condition improves, he is told that he can “marry” in four years. To make sure he follows doctor’s orders, Mathieu and the doctor go together to a hospital to see syphilitic lesions. First, they visit a glass blower with a dark lesion growing over his lower lip. Animation switches to live action and we see a real patient, staring helplessly into the camera. Another live-action shot shows a leg with an inflamed lesion, dark and swollen, bubbling out of the skin. Audience members need to be convinced of the debilitating nature of syphilis, and seeing real patients is impactful in a way that animation can never be.

Mattéo, unlike Mathieu, has not gone to see a real doctor. Pocks cover his face and he develops a rash and a fever. A year later, while still contagious, he commits a “veritable crime” by marrying. His wife has seven miscarriages in five years. The children they do have are infected with congenital syphilis. One uses a cane. Another is hydrocephalic. A third is cognitively affected, an “idiot.” Ten years later, Mattéo’s nose collapses in a scene that could be Pinocchio rewound. Twenty years later, he believes that he is an emperor — late-stage syphilis can cause dementia-like symptoms. Mattéo dies.

A title card reminds us that syphilis doesn’t just affect one individual; it can be disseminated to the next generation. It can swim into bodies of different nationalities. Cut to the responsible Mathieu, happy father of at least five, sitting beneath a framed portrait of his doctor, “my savior.”

On Doit Le Dire presents syphilis as a social disease, and through narrative aims to influence the precautions men take when deciding to have sex. What spirochete bacteria do in the dark cannot be controlled, the film suggests, and so people must control themselves.

IV.

[T]hrough M. Comandon’s beautiful researches we are not only able to penetrate into the intimate life of the living blood and its parasitic inhabitants, but also to study the processes of reaction and defense […] you will see the life that no other form of photographic process can reproduce.

— surgeon Rudolph Matas, Southern Medical Journal, September 1912

Through his work on Spirochaeta Pallida over 100 years ago, Jean Comandon conceived a scientific application for cinema. Similar to the ways in which physiologist and inventor Étienne-Jules Marey developed methods for sequentially photographing bodies to reduce motion to its constituent parts, Comandon invented a means of deconstructing the motion of miniature actors within a microscopic frame. Though he could not have known it at the time, Comandon’s films would become early entries in the science film genre — and early exemplars of the camera usurping the naked eye for the sake of scientific research and entertainment.

¤

LARB Contributor

Sonia Shechet Epstein is executive editor and associate curator of Science and Film at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York City. She curates the Museum’s film series Science on Screen, and runs their online publication Sloan Science & Film (scienceandfilm.org). Sonia is a founding mentor at the New Museum’s incubator NEW INC, and has lectured internationally about the intersection of science and film. She graduated with a BA in Psychology and Art History from Middlebury College and is a master’s candidate in Experimental Humanities at NYU.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Everybody Hurts

Travis Rieder’s “In Pain” provides us with a bioethics that is not passively analytical, but peacefully agitative.

The Enlightenment’s Venereal Imagination

A new book about how 18th-century writers and artists grappled with the reality of STIs.

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!