What Astral Weeks deals in are not facts but truths. Astral Weeks, insofar as it can be pinned down, is a record about people stunned by life, completely overwhelmed, stalled in their skins, their ages and selves, paralyzed by the enormity of what in one moment of vision they can comprehend.

— Lester Bangs

We have novels that give us greatly a three dimensional world: here is a narrative that gives a new dimension.

— Padraic Colum on Finnegan’s Wake, the New York Times, May 7, 1939

WHEN IT COMES to TV, the nature of freedom slides between two poles: commitment and obsession. Some shows you bet on, putting in the hours hoping for a reward; others you can’t stop watching even as they descend into increasing absurdity.

On one level, the difference comes down to a matter of taste, and most likely only a matter of mood, comparable to the choice between watching Tree of Life or Die Hard. But when evaluating the most acclaimed TV dramas of the past decade, the matter becomes more serious. It took me a year to watch The Sopranos, about six times as long as it took me to watch all five seasons of The Wire twice. Those are two essentially different viewing experiences for shows that otherwise, in terms of quality, are hard to parse, raising the question of whether the ability to get us hopelessly addicted gives The Wire the slightest competitive edge.

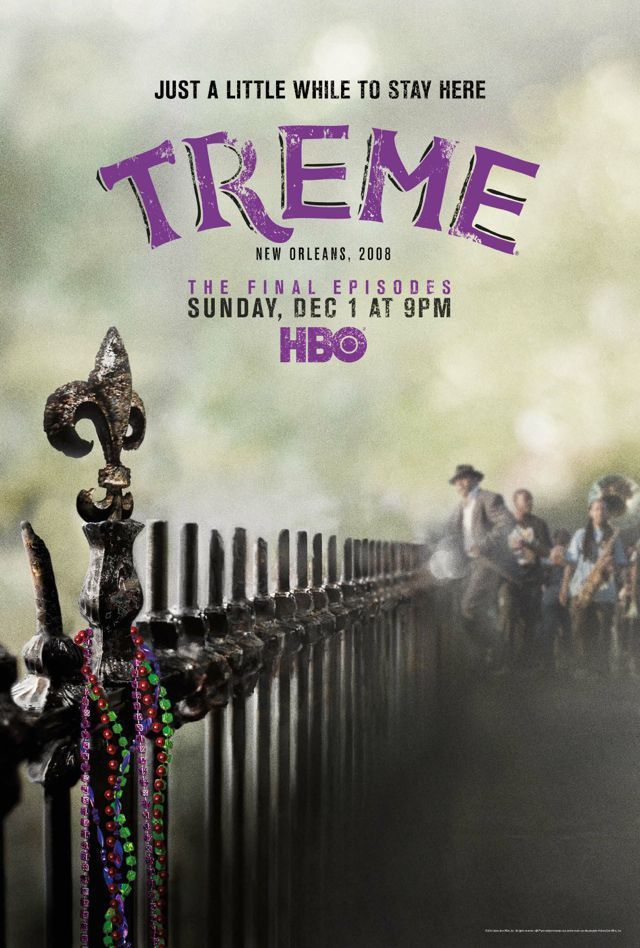

Because I’ve watched Treme in real time since it began, I can’t give you a comparative figure. But I can tell you that it’s not a show to binge on. Its episodes are full Thanksgiving meals. I have a close friend who, out of a shared love of all things New Orleans and The Wire, began the Treme journey with me. After the second season, I was going it alone. The show was too much, she said: too much sadness, too much anguish, too much stress. She loves it. She can’t watch it.

Let this article stand as my semi-public shaming of her decision, my attempt to bring her and others like her back into the fold. Because Treme may be the TV drama that requires most commitment from us, but it’s also the most unique and ambitious show of this golden age of television in which we find ourselves.

¤

Treme is a show about New Orleans, so long as we’re clear about what that means. It doesn’t mean documentary veracity. We may take confidence from the fact that David Simon, the show’s creator along with Eric Overmyer, is a former journalist presumably obsessed with the facts, or celebrate the realism offered by the abundant celebrity cameos in each episode, but watching Treme to learn about New Orleans is as foolish as claiming to know anything about Baltimore because you’ve seen The Wire. In both cases, whatever you learn about the cities from watching the shows is an added bonus.

Saying Treme is a show about New Orleans also doesn’t mean its outlook shares the rose-colored enthusiasm of a tourism ad. As much as the show celebrates the city and might be described as a love letter to it, the darker aspects stay firmly in view. In fact, the dirt and the shine are intertwined, more so even than in The Wire, which made a point of how every businessman has a little drug dealer in him and vice versa, while also delivering a tale of two cities message, with the haves and have-nots demarcated clearly both geographically and morally. That separation exists in Treme, but not in the show directly: the haves are those living outside of New Orleans, refusing to help, refusing to care for the city’s plight. Those left have their differences and their divisions, but they share a sense of abandonment that, along with the city’s music and Mardi Gras, binds them.

There are, therefore, two faces to New Orleans in Treme. One is the prideful visage presented to the rest of the world, predicated largely on the city’s cultural importance. It’s the “realness” that John McWhorter complained about in The New Republic, the part of the show that might feel like a public service announcement about how much cooler New Orleans is than the rest of the country, especially New York, its most consistent opponent.

But the show has an inward looking face as well — one more reflective and critical. In Treme, community gives and takes away in equal measure. Sonny (Michael Huisman), a Dutch guitarist who starts off as a selfish junkie in season one, drowns from the partying, the drugs, the laissez-faire permissiveness of his adopted town before he’s saved by a musician who takes it upon himself to force him out of his hole. Salvation, though, means leaving New Orleans, and after Sonny isolates himself on a fishing boat and eventually finds peace and a new stabilizing love, the question becomes if he can ever return.

Antoine (Wendell Pierce), a charming if unreliable trombonist, confronts the same problem in each season. There’s a side of him that takes care of his kids and finds pleasure in his work as a music teacher, a job that incidentally also provides a steady salary for him and his family. But he can never fully embrace that life, repeatedly surrendering to the temptations of a gigging routine that lets him fulfill his musician dreams while also turning him into a drunken, cheating mess.

The two faces of New Orleans equally complicate the question of whether to leave or stay in the city, a central dilemma for a show that marks the chronology of its seasons by their distance from Hurricane Katrina — three months after, fourteen months after — and that focuses often on the residents who fled the storm and were later denied the opportunity to return to their homes.

In the cases of these refugees, going back to New Orleans was a prerogative denied, whether due to insurance nightmares or government obstruction. For others, though, remaining in New Orleans is a career suspended. Over the course of the show, both Janette (Kim Dickens), a chef, and Delmond (Rob Brown), a successful modern jazz trumpeter, must decide between New York and their hometown, the former best suited to reward their talents and contemporary taste, the comforts and traditions of the latter calling them back regularly.

The fraught decision to stay or go is most tragically accentuated in LaDonna (Khandi Alexander), a bar owner who in progressive seasons finds out her brother’s dead body remained unidentified for months after the storm due to the neglect and incompetence of the police; gets raped and watches her assailant go free due to a mistrial; and whose bar is destroyed by an arson attack. She loses everything to her city but refuses to leave.

Such loyalty to New Orleans is a quality the show unequivocally champions. But the stakes of the choice are always clear: New Orleans is a city that inspires obsession, from locals and outsiders alike, but staying is a question of commitment. Always in Treme, New Orleans is a city of unimaginable cultural wealth, a great city that “lives in the imagination of the world,” as rowdy English professor and political commentator Creighton (John Goodman) puts it in the first season. But the question remains: is it a city that elevates its citizens or demands their total sacrifice?

Treme’s singular quality is how it circles this argument, presenting one side of the equation, coming back around to the other, never really settling and so allowing New Orleans to be saint and devil all at once.

¤

At the level of episode, season, and show, Treme functions like an accelerating spiral. The setup is often protracted. The scenes are short and to the point. Longer ones are intercut with each other. With slowly increasing intensity, the show spins us through its various storylines, the musical interludes acting as a motor that ratchets up the emotions. The point here is not how lives intersect. Many of the characters know and interact with each other, but their stories function independently, their main commonality being the city around which they all revolve.

In contrast to the tortured anti-hero chronicles of The Sopranos, Breaking Bad, and Mad Men, Treme lacks a true protagonist. Instead it uses its characters to map out different points in the life of its city, spreading out a full emotional spectrum in each episode. Take the finale of season three: As Davis (Steve Zahn), a local DJ, plans to end his musical career, he receives a needed vote of confidence from fellow musicians; meanwhile, Terry (David Morse), a police lieutenant, finds himself increasingly ostracized and threatened in a homicide department that values loyalty over his investigative work. One wave comes in, and another recedes; every moment must be countered by its opposite.

What defines Treme is not that it contains disparate elements but that it affords them all equal space and validity. The first episode of the upcoming fourth season opens on Election Day, 2008. Albert (Clarke Peters), a headstrong Mardi Gras Indian chief, refuses to vote, even for Barack Obama. “What? Do you think that’s gonna change some shit,” he challenges his son and daughter, at which point we cut immediately to John Boutté, a New Orleans musician regularly featured in cameos, singing “A Change Is Gonna Come” outside of a polling station. Both moments — the skepticism and the elation — are equally necessary, equally sincere.

Treme thrives on such conflicted and competing claims, much like the New Orleans that Tom Piazza, a journalist and writer for the show, describes in his book of essays, Devil Sent the Rain:

If there is a single factor most responsible for the extraordinary distance New Orleans has traveled in the years since its near-death experience, it is the city’s culture. Not only the city’s music, dance, funeral traditions, cuisine, and architecture – its look and its smell and its feel and its sense of humor – but the interaction among all these factors, their coordination, is what makes the city live, what makes it alive, in its unique way.

Treme’s New Orleans is a city of such multiplicity, bringing disparate themes, characters, and emotions into a room and letting them bounce off each other like atoms. In that respect, perhaps what makes the show challenging is its requirement that we shift our preconceptions of how a TV show is to run. Treme is not a train carrying its characters from Mr. Chips to Scarface or from the opening of a case to its conclusion. It’s a set of building blocks slowly stacked until a formidable structure teeters before us, weighty enough to crush us, sweeping enough to envelop us.

That method comes with a trade off. The Wire’s greatness results largely from its clarity of vision, a sharp intellect that allows it to open its episodes with summarizing quotes pithy enough to now inspire a line of t-shirts. The show has no muddle and no diversions. Each season has its focus, its thesis, and its well-oiled execution.

Treme, on the other hand, embraces the sloppiness of rambling, the messiness of piling facts upon facts. In the finale of season one, the fact is LaDonna dancing to the marching band at her brother’s funeral after months of searching for his body; the fact is Toni (Melissa Leo) refusing to have a similar send-off for her husband, Creighton, who committed suicide, because you “can't dance for 'em when they quit.” The facts are Creighton’s raw YouTube videos denouncing post-Katrina policies — “fuck you fucking fucks” — and Davis’ raucous anthems — “motherfuck all you fucking bitches” — but also the solemn words of a song performed by Annie (Lucia Micarelli) — “this city won’t wash away, this city will never drown” — and Chief Albert’s repeated phrase: “Won’t bow, don’t know how.”

Or there’s the first scene of season two: the locally-renowned Brocato’s has reopened over a year after the storm and brought its famous lemon ice back to the city; Albert tends to his wife’s grave as LaDonna visits her brother’s at the same cemetery; a young boy, just starting to learn the trumpet, plays the opening notes of “Oh When the Saints.” These are the facts.

The truth, though? It’s in the mixture of these elements, or maybe caught in the spaces in between, hard to glimpse, and rewarding of patience. It’s bittersweet, riddled with compromises, unstable, and just about ready to bowl you over.

¤

Tomas Hachard is an Editorial Assistant for Guernica Magazine.

LARB Contributor

Tomas Hachard is an Editorial Assistant for Guernica Magazine. He has written about art, politics, and himself for NPR, The Morning News, and The Millions, among others. Follow him on Twitter: @thachard.

LARB Staff Recommendations

A Time-Lapse Detective: 25 Years of Agatha Christie’s "Poirot"

For the past 25 years, viewers have watched an actor and character grow and change together, episode by episode, year by year: a time-lapse detective.

DEAR TELEVISION

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!