“The Stamp is Never Neutral”: Vincent Sardon’s “The Stampographer”

Stamps can terrorize because while their materiality exists in time, like that of paintings, it also compacts it.

By Mairead CaseJanuary 21, 2018

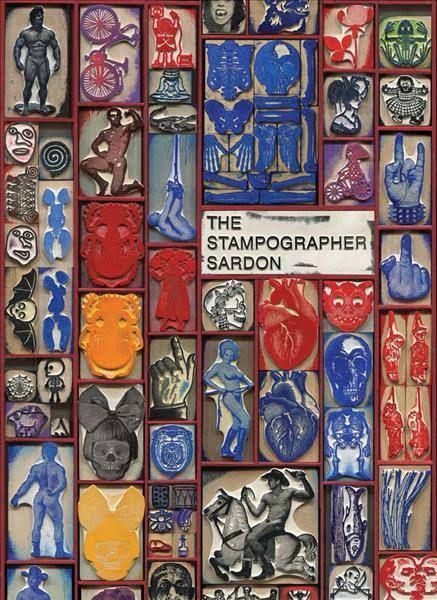

The Stampographer by Vincent Sardon. Siglio. 108 pages.

“THE STAMP IS never neutral,” Vincent Sardon tells Richard Kraft and Lisa Pearson in an interview translated by Philippe Aronson and included in Sardon’s new book The Stampographer. “It packs a symbolic wallop.” He’s right. Think of judges, cops, customs officials, the powers at the border and on the opposite side of the glass. Think of how they use stamps to validate, destabilize, define. To record and expunge. In one move, Sardon notes, people formalize “all sorts of evil documents that have the power of putting people in impossible situations.” Stamps can terrorize because while their materiality exists in time, like that of paintings, it also compacts it. It finalizes as it presses. As it smears. Suddenly, immediately, the women are married women. Suddenly, the parent must leave the country. Suddenly, it’s clear. It’s paid. Our vacation was great.

Even multiplied across several sheets of paper, stamps never lose their wallop. In the same interview, printed here, Sardon remembers the day one of his drawings appeared on the cover of Libération, the (now, mostly) center-left daily newspaper in France. Thirty-thousand copies were distributed, but “nobody gave a shit.” Smoothly duplicated, any image starts to drone, and eventually turns to film. But the analog stamp is a powerful tool: an image representing a specific action taken by an individual. This realization, says Sardon, is what led him to leave his desk at Libération and start making hundreds and hundreds of stamps in a live-work studio beneath Place de Clichy. Sardon filled the place with machines, books, and a scavenged bed. Here he “began to turn my life into material, and it felt more powerful than any caricature about French fiscal reform ever did.” This was another form of power, and Sardon devoted himself to it.

Here in the reality-hungry United States, the wolf leaving his pack sounds obvious and expected, but Sardon doesn’t really seem to care about American-style individualism. Instead he’s grossed out by corporate or political power, especially when it demands binary thinking and unexamined unity. Newspapers present themselves as free entities, as groups of like-minded people who can say what they want, but in reality, most are owned by corporations expecting a slant. This isn’t all bad, especially if that slant is your slant. But ultimately it restricts creativity and nuance.

Sardon remembers a day in the newsroom when Ségolène Royal was running for president. While drawing her “as a granny-type lady with the dimly illuminated eyes of a Charismatic Christian” — Sardon is a storyteller above all — he was interrupted by a journalist, pen in hand. She told him his drawing needed to be more beautiful, and stepped in to make it so. At this point, Sardon said, he realized he was doing PR, not making art. And while he says he never intended to transgress anything specific, at Libération or now, Sardon admits (and enjoys, and works toward) the way stamps allow him to reveal “the grimmer aspects of life in Paris, the city’s violence, the brutality of its politics, the sleazy sexuality on display in the Pigalle neighborhood, the hatred I would sometimes see on people’s faces.”

Working this close to one’s doorstep will sometimes be transgressive, simply because not everyone thinks the same way. In this sense Sardon’s work appears to be deeply personal. It’s distanced from the traditional newsroom, and closer to, say, the 1990s mimeograph revolution or L’Association, the French comics collective: art-tools scaled to the body, and that body’s individual experience, shared with other bodies living in the world.

The Stampographer, like most Siglio Press titles, is a handsome, cleverly designed text that asks readers actively to engage with a world that may or may not be familiar to them. The book could be read in spaced-out bites from a coffee table; three times pell-mell on one commute; or non-linearly, in chunks. It starts with 86 full-color pages of Sardon’s art and work and concludes with the 12-page interview by Kraft and Pearson, in which Sardon discusses his habits, drives, and influences. Topics include gentrifying neighborhoods (fewer old ladies and drunks, more “better-dressed alcoholics”), books (“I still enjoy reading about flying saucers, werewolves, and duck breeding”), and his childhood in Basque country. The interview is illuminating, more like a chat between makers than blind publicity or boxing-ring criticism.

Sardon is firm about his practice, which is rooted at once in experience and “utter uselessness” (a stamp isn’t food, it isn’t a roof). There is a punky purity here too. Sardon is clear about the struggle required by this life, even as he knows there is no other way for him to live. Sometimes his brain turns murky from poverty. Sometimes artists — the horror! — knock on his studio door.

In the interview Sardon never calls himself an artist, though he has been an art student, and a member of art collectives. Instead of rooting his origin story in comics collectives or other alt spaces, or artifice, or simply being an endearingly crabby outsider, Sardon references class, in the form of the cruddy summer jobs he had as a kid. One was at an insurance company, where he spent whole days stamping TO BE DESTROYED on stacks of cancelled contracts. He remembers enjoying reading these contracts, and the violence of stamping them. Again, the stamp — the tool — is the thing. The stamp rejects, so it exists.

Sardon began showing and selling his stamps and other works in 2007, almost a decade before 12 people were murdered and 11 injured at the offices of the satirical leftwing weekly Charlie Hebdo. (The cardinal directions of French politics don’t match American ones.) Sardon says he tried to make a statement after the murders, especially as social media bloomed out boring storms of bloody doves and weaponized pencils, but “nothing came except tears.” Mourning shimmers, so it doesn’t really work in the fixed world of stamps, and this incident in particular did not lend itself to binary thinking: violent murders are wrong, but so is racist imagery.

So what does Sardon depict in The Stampographer? The first two pages of his book, after endpapers featuring blue fists flipping the bird, are simply his stamps. These are photographed, their inkpads winking up against a white background. But because the images the stamps are meant to reproduce are all city buildings, at first the reader sees a swirled, hallucinatory city block, with mirror-image signs (“IDEAL HOSIERY: LADIES & MEN’S HOSIERY,” “GUNS CHANGE LIVES!”), jumbled buildings (a snowy walk-up next to a silo), and graffiti printed from actual holes dug into the rubber. All text is in English, and it’s not clear whether the originals were too.

This opening scene is both familiar and cross-eyed, granting permission to read these pages in non-linear order, and to privilege image over text (which might seem obvious, in a book about stamps, but it’s not). Each image is made once, but on the next page, the reader reads a printed scene, with everything “in order” plus some duplication: a solidly worn, not-quite-yet-gentrified city block. The remaining signs are now legible: “STOP EVERY THING.” “YOU ARE NOT FREE.” The phrases snake into the rest of the reader’s day. It’s easy to imagine them as refrains, warnings, jokes. And so they live.

Next are several pages of wood-handle stamps, resting just above printed statements that read like junior-high mash notes. They’re dirty (“Curate my ass”), and funny (“Right wing punk rocker”), and translated into English from the original French, Romanian, Japanese, and Russian by Laura Park, Maureen Forys, Mia Trifa, Ryoko Sekiguchi, Dr. Laurent Zarnitsky, and J-L Mélenchon.

And then, the form spirals open: a man made up of 15 stamps, with joint separation, cheerful toes, and a face like the Shroud of Turin, is double-printed so that it appears he’s having sex with another himself. This is obviously a charged image — Jesus having sex, Jesus having sex with Jesus, queer Jesus, two people having sex while staring directly and solemnly at the viewer — but most immediately it’s really funny. Media-wise, it’s almost film, but not quite. Following the neighborhood and the solemnly sexy Jesus are pin-ups (including male genitalia, body hair, and extra red ink after spankings), brayers spinning out tanks and fighter planes, bugs, red and blue 3-D-esque ventriloquist dolls, and corpses with lips swollen in springy pastels.

Unsurprisingly but hilariously, Sardon pokes fun at the fine art world: there are paint-spatter stamps, breast-hips-and-torso stamps, and Lichtenstein and Warhol knockoffs. While snarky and fast-paced, Sardon’s work never slips into predictability. He gives us a sequence, for example, in which a man gains face and neck tattoos, and more face and neck tattoos, and then these are stripped away and we see the man’s facial muscle. And for all the naked bodies, there is virtually no gender commentary. The viewer sees breasts and penises and can just look at them. The stamp does not mean, it is. The only words the reader encounters prior to the interview are either printed on the aforementioned buildings or across the aforementioned man’s lip, which says COMPTON. Is this the original? A translation? Does it matter?

If stamps are tools, and if owning them is power — for everyone, which Sardon stresses by selling his stamps at a reasonable price from his studio and online — then what is a book about the images they make? This one is beautiful, but also funny, and thus true. The word “stampographer” (“tampographe,” in French) is rooted in the word “tampon” — a piece of cloth to stop a hole. The word wasn’t associated with bleeding bodies until 1848, but by 1620 it was known as a wooden plug, jammed into the muzzle of a gun like a cork in a half-full wine bottle, and used to keep out rainwater. Keeping that etymology in mind, we might say that at their best Sardon’s stamps both keep out the chill, and help us keep our aim true.

¤

LARB Contributor

Mairead Case (maireadcase.com) is a teacher, writer, and editor in Denver. She teaches writing and English in Denver Public Schools, the Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, and the Denver Women's Jail. Mairead holds an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a PhD from the University of Denver, and has been a legal observer with the NLG for over a decade. Tiny is a novel and a translation of Antigone, forthcoming from featherproof books on 10/20/20.

LARB Staff Recommendations

Comics Conceptualism

Trevor Strunk on “Terms and Conditions,” the new graphic novel by R. Sikoryak.

The High-Rise is a Bottomless Abyss

Brad Prager on Hariton Pushwagner's "Soft City."

Did you know LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes daily without a paywall as part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and engaging writing on every aspect of literature, culture, and the arts freely accessible to the public. Help us continue this work with your tax-deductible donation today!